Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry Emily Rutter

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014 Constructions of the Muse: Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry Emily Rutter Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Rutter, E. (2014). Constructions of the Muse: Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1136 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Emily Ruth Rutter March 2014 Copyright by Emily Ruth Rutter 2014 ii CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY By Emily Ruth Rutter Approved March 12, 2014 ________________________________ ________________________________ Linda A. Kinnahan Kathy L. Glass Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ Laura Engel Thomas P. Kinnahan Associate Professor of English Assistant Professor of English (Committee Member) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ James Swindal Greg Barnhisel Dean, McAnulty College of Liberal Arts Chair, English Department Professor of Philosophy Associate Professor of English iii ABSTRACT CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY By Emily Ruth Rutter March 2014 Dissertation supervised by Professor Linda A. -

Local Party Organizations and the Mobilization of Latino Voters

LOCAL PARTY ORGANIZATIONS AND THE MOBILIZATION OF LATINO VOTERS A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Daniel G. Lehman May, 2013 Examining Committee Members: Robin Kolodny, Advisory Chair, Political Science Michael Hagen, Political Science Sandra Suarez, Political Science Rosario Espinal, Sociology i ABSTRACT We frequently hear that Latinos are the fastest growing minority group in the United States. We also know that like many American immigrant groups, Latinos tend to reside in states where a critical mass of their community already is settled, in this case largely for geo-political reasons (e.g. New Mexico, Arizona, California, Texas, Florida and New York). Why, then, is Latino participation in national politics lower than white, Black, and Asian voters? And who has an interest in doing something about it? This project addresses several interrelated questions concerning the place of Latinos in American politics and the health of democracy in the United States. Political parties are meant to link citizens to the state. However, parties often fear that reaching out to certain groups may alienate the concerns of some core voters, providing a disincentive to political parties to prioritize Latino outreach. Here, I ask, to what degree are local political parties involved in mobilizing Latino voters as compared to other voting groups? Interest groups have much narrower constituencies than political parties by definition, but their -

Eget a Head Start on the Holidays & SHOP LOCAL This Season

Get avery head year, the icy Southwest startand onmuch more! the Head down andholidays find that unique gift this and& so m uchSHOP more! Attendees will LOCALreceive free market takes this place at the Livingstonseason Civic Center. Montana temps and snow cover you’ve been pondering. The Holiday Bazaar is a tote bags while supplies last. Please also bring nonper- Also on Dec. 2nd, the Antique Market will host signal the fast approaching season fundraiser for the Emerson Center. ishable food items to donate to the Gallatin Valley the return of its Holiday Open House of giving. That’s right, it’s time to Also at the Emerson on Nov. 18th, the Bozeman Food Bank. Extravaganza! from 10am–5pm. Come for sales start making those lists, and check- Winter Farmers’ Market moves upstairs for its Looking to early next month, the 2017 SLAM throughout the store, refreshments, and plenty of ing ‘em twice. In prolonged recog- weekly event. Vendors will be displaying their goods Winter Showcase heads to the Masonic Lodge good cheer! This event is meant to wish everyone the nition of “Small Business from 9am–noon. Pick up some groceries, stock the Ballroom Friday and Saturday, December 1st–2nd happiest and healthiest of holidays. Get ready to Saturday,” consider shopping local pantry for Thanksgiving, and get a jump on holiday from noon–8pm both days. With the continued goal wrap and “Come See What Time Left Behind” in when checking names off your holiday shopping shopping with this pre-holiday extravaganza at the to Support Local Artists and Musicians, this holiday Four Corners. -

FIP Partenaire De BANLIEUES BLEUES

EDITO EE>G>F:GJN>I:L=>LHN?>L E:?<A>=>:GEB>N>LE>N>L IHNK<>MM>GHNO>EE>b=BMBHG $HLAN:,>=F:G .A>-HNE,>;>EL K<AB>-A>II>M)EBO>K&:D> K:GaHBLHKG>EHNI E> 1HKE=-:QHIAHG>+N:KM>M:O><%B==$HK=:G A:KE>L&EHR= 'B<A>E*HKM:E HG:E=":KKBLHG #G@KB=&:N;KH<D ,HR(:MA:GLHG RKHG1:EE>G .>K>G<>E:G<A:K= >GMMNR:NQ=><NBOK>L >G?HEB> (B=><H??K>A:KF:BG>(>OBEE> =>%:;:E AN<D*>KDBGL '>LA>EE(=>@>H<>EEH %A:E>= >j:M<AB:KR E:<DDHE=F:=BG: $HLb$:F>L &CBEC:G:NMME>K 1:LBLBHI ,H<DBGHILB>$K '>EBLL:&:O>:NQ ,H;RG)KEBG>ME>*ANIANF:&HO>'BGNL 0HBQ=>FB>EHN=>KbOHEM> .HNME>FHG=>E>L:BM E:;HGG>FNLBJN>b;K:GE>E>LFNKL=>$bKB<AH =HGG>=>L?HNKFBL =:GLE>LC:F;>L E:?HK<>=b<A:II>K\E:MMK:<MBHGM>KK>LMK> EE>?:BM;KBEE>K=>L>NKL=:GLE: GNBM KbObE:GM=BGHNiLFbE:G@>L=><HNE>NKL =>?KNBMLK:K>L =>?NO>L<E:G=>LMBG>L(HeE D<AHMb ':K<,B;HM $HAGGR&:':K:F: B>LM:(H<MNKG: -HE B@*HI HG@HING+ E>L 1BE=':@GHEB:L EE>L><HN>E:FbFHBK>=:GLMHNLE>LL>GL K>LLHKMBEEB>"HEB=:R .A>EHGBHNL 'HGD KB<HEIARHN-MN??-FBMA=NFNLb>=N-Bc<E>=N$:SS MINBLJN>EE>IKbL>G<> LNKL<cG>&><HKIL=>LFNLB<B>GL =>LFNLB<B>GG>L >LMBFIHLLB;E> \GNFbKBL>K \MbEb<A:K@>K #KK>FIE:a:;E> F:BLI:LBGMHN<A:;E> INBLJN>I:K<>GM:BG>L C>NG>L>MFHBGLC>NG>LL>FdE>GM:NQ:KMBLM>LBGOBMbL>ML>FFdE>GMIHNK<HFIHL>K LHN?>K <A:GM>K ?K:II>K =:GL>K MK:O:BEE>K BFIKHOBL>K I:K:=>K BGO>GM>K=>IKb<B>NL>L?:aHGL=> OBOK>>GL>F;E> M=:GLE:BK=><>L:9FDA=M=K:D=M=K B<B>ME\ ;:L <HFF>NGI:K?NF=>G?:G<> (HGI:L=> I:K:=BLI>K=N =>G?>K=BLI:KNI>NM dMK>:O><NGIE:M>:N:KMBLMBJN>>Q<>IMBHGG>E E:(HNO>EE> )KEb:GL M>KK>IKHFBL>=NC:SS =NKH<D =>E:LHNE>M=N?NGD >LMEBGOBMb> LIb<B:E>=N?>LMBO:E -BGBLMKb>BER:MKHBL:GL >GIE>BG>K>G:BLL:G<> :NCHNK=ANB>MF:BGM>G:GM -

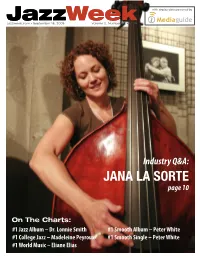

Jazz Radio Panel P. 22 Jazzweek.Com • September 18, 2006 Jazzweek 13 Airplay Data Jazzweek Jazz Album Chart Sept

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • September 18, 2006 Volume 2, Number 42 • $7.95 Industry Q&A: JANA LA SORTE page 10 On The Charts: #1 Jazz Album – Dr. Lonnie Smith #1 Smooth Album – Peter White #1 College Jazz – Madeleine Peyroux #1 Smooth Single – Peter White #1 World Music – Eliane Elias JazzWeek This Week EDITOR/PUBLISHER Ed Trefzger MUSIC EDITOR Tad Hendrickson kay. After beating up on jazz radio a little bit over the last CONTRIBUTING WRITER/ three weeks, I thought I’d better balance it out with some of PHOTOGRAPHER Othe things jazz radio does right and does better than other Tom Mallison formats. PHOTOGRAPHY 1. Jazz radio plays more new artists than any other profes- Barry Solof sional format. Over the last three years, at least 600 albums have Contributing Editors made the JazzWeek top 50. No commercial radio format plays Keith Zimmerman that many new records in a year, and other than some non-comm Kent Zimmerman triple-As and college radio, no other radio genre comes close. (We Founding Publisher: Tony Gasparre can argue about how many of those should be played, but it’s still ADVERTISING: Devon Murphy an impressive and commendable number.) Call (866) 453-6401 ext. 3 or 2. Jazz radio is not part of the whole sleazy money/payola mess. email: [email protected] The lack of money in jazz is certainly part of that, but the relation- SUBSCRIPTIONS: ships between promoters, labels and radio are built on trust, not Free to qualified applicants free electronics, wads of cash, limos or vacations. -

James Baldwin and Ray Charles in “The Hallelujah Chorus”

ESSAY “But Amen is the Price:” James Baldwin and Ray Charles in “The Hallelujah Chorus” Ed Pavlić University of Georgia Abstract Based on a recent, archival discovery of the script, “But Amen is the Price” is the first substantive writing about James Baldwin’s collaboration with Ray Charles, Cicely Tyson, and others in a performance of musical and dramatic pieces. Titled by Baldwin, “The Hallelujah Chorus” was performed in two shows at Carnegie Hall in New York City on 1 July 1973. The essay explores how the script and presentation of the material, at least in Baldwin’s mind, rep- resented a call for people to more fully involve themselves in their own and in each other’s lives. In lyrical interludes and dramatic excerpts from his classic work, “Sonny’s Blues,” Baldwin addressed divisions between neighbors, brothers, and strangers, as well as people’s dissociations from themselves in contemporary American life. In solo and ensemble songs, both instrumental and vocal, Ray Charles’s music evinced an alternative to the tradition of Americans’ evasion of each other. Charles’s sound meant to signify the his- tory and possibility of people’s attainment of presence in intimate, social, and political venues of experience. After situating the performance in Bald- win’s personal life and public worldview at the time and detailing the structure and content of the performance itself, “But Amen is the Price” discusses the largely negative critical response as a symptom faced by much of Baldwin’s other work during the era, responses that attempted to guard “aesthetics” generally— be they literary, dramatic, or musical—as class-blind, race-neutral, and apolitical. -

Backstage Guide 1

BACKSTAGE A publication of COMMUNITY SERVICE at AMERICAN BLUES THEATER Days of Decision - the music of Phil Ochs BACKSTAGE GUIDE 1 BACKSTAGE DAYS OF DECISION THE MUSIC OF PHIL OCHS Devised & Performed by Zachary Stevenson ABOUT THE ARTIST ZACHARY STEVENSON (performer & creator) is a proud Artistic Affiliate of American Blues Theater. He is an award-winning actor, musician and writer. Originally from Vancouver Island, Canada, Zachary has been coined a “dead ringer for dead singers” by the Victoria Times Colonist for his portrayals of Buddy Holly, Hank Williams, Phil Ochs and roles based on Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis. In 2018, Zachary won the Jeff Award in Chicago for Outstanding Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role (Musical) for hisArtistic portrayal ofAffiliate Buddy Holly Zachary in Buddy - StevensonThe Buddy Holly Storyhonors, a role he folk’s honed music in more legend than a dozenPhil Ochs productions across Canada and the United States. Other actingwith highlights this musical include Million tribute. Dollar Quartet , Hair, Urinetown, Assassins, and Company. Zachary has produced and recorded five independent albums and tours frequently as a musician. He is also active as a music director on productions such as Ring of Fire, Million Dollar Quartet, and American Idiot (upcoming). He is currently writing an American Blues commissioned solo show based on the life of folksinger, Phil Ochs. 2 AMERICAN BLUES THEATER TABLE OF CONTENTS About the Artist ................................................................................................................ Page 2 About Phil Ochs …………………………..........……..................................................................Pages 4-5 Protests & Music: 1900 - Today .................................................................................... Pages 6-7 Register to Vote Online & In-Person ................................................................................. Page 8 When Do You Need an ID to Vote? .................................................................................. -

Sonny Rollins

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • October 30, 2006 Volume 2, Number 48 • $7.95 Radio Q&A, Part II: WBGO’s GARY WALKER page 10 On The Charts: #1 Jazz Album – Diana Krall #1 Smooth Album – The Jazzmasters #1 College Jazz – Madeleine Peyroux #1 Smooth Single – The Jazzmasters #1 World Music – Acoustic Africa JazzWeek This Week EDITOR/PUBLISHER Ed Trefzger pin counts are down a bit this week. On the jazz side, MUSIC EDITOR Tad Hendrickson it’s fundraising time for many stations, but a contribu- Stor is some downtime at Mediaguide: “Due to the sys- CONTRIBUTING WRITER/ tem-wide infrastructure crash on October 10, Mediaguide is PHOTOGRAPHER Tom Mallison still in disaster recovery mode. We continue to find and cor- PHOTOGRAPHY rect problems as we uncover them. As a result, there still may Barry Solof be missing airplay information from reports, charts, and sta- Contributing Editors tion logs. We are working hard to correct all problems. We Keith Zimmerman appreciate your understanding during this time.” Kent Zimmerman Founding Publisher: Tony Gasparre hen the change of programming at WBEZ was an- ADVERTISING: Devon Murphy nounced in the spring, the station said the loss of Call (866) 453-6401 ext. 3 or Wmusic programming would be replaced by innovative email: [email protected] and interesting new programming promoting the arts. SUBSCRIPTIONS: Now it’s reported in Chicago that the 8 p.m. to midnight Free to qualified applicants Premium subscription: $149.00 per year, weeknight jazz will be replaced by reruns of daytime shows, w/ Industry Access: $249.00 per year including the syndicated “Fresh Air.” To subscribe using Visa/MC/Discover/ AMEX/PayPal go to: They are all fine programs, but it seems like podcasting http://www.jazzweek.com/account/ – which the station and NPR already do – is a better way to subscribe.html timeshift programs, rather than duplicating four hours of the broadcast day. -

Incorporating BLUES WORLD MISSISSIPPI FRED Mcdowell 1904-1972

Blues~Link4 incorporating BLUES WORLD MISSISSIPPI FRED McDOWELL 1904-1972 X T R A 1136 (R.R.P. inc. VAT— £1.50) Recorded in 1969 at Malaca Studios, Jackson, Mississippi. Produced by Michael Cuscuna WALTER ‘SHAKEY’ HORTON w ith HOT COTTAGE WAIIER ‘IHAHEV HOfiVOM X T R A 1135 (R.R.P. inc. VAT — £1.50) Recorded in 1972 at Parklane Studios, Edmonton, Canada. Produced by Holger Petersen for further information about these and other blues albums in the Transatlantic Group Catalogue, write to Dept. BU/3 Transatlantic Records, 86 Marylebone High Road, W1M 4AY Blues-Link Incorporating Blues World 94 Puller Road, Barnet, Herts., EN5 4HD, U.K. EDITOR - Mike Black ASSISTANT EDITOR - Alan Balfour LAYOUT & DESIGN - Mike Black SUBSCRIPTIONS: 25p a single copy postpaid. 1 year’s subscription (6 issues) £1.50 ($4.00 surface, $8.00 air mail). Overseas subscribers please pay by IMO or International Giro. Personal cheques w ill be accepted only if 25p is added to cover bank charges. Blues-Link Giro Account Number — 32 733 4002 All articles and photos in Blues-Link are copyright and may not be reproduced without the written permission of the Editor although this permission will normally be freely given. © Blink Publications 1974 DUTCH AGENT: Martin van Olderen, Pretoriusstraat 96, Amsterdam-oost, Holland. GERMAN AGENT: Teddy Doering, D-7 Stuttgart 80, Wegaweg 6, Germany. SWEDISH AGENT: Scandinavian Blues Association (Mail Order Dept.), C/o Tommy Lofgren Skordevagen 5,S — 186 00 Vallentuna, Sweden. Cover photo: Alex Moore by Chris Strachwitz. Typeset by Transeuroset Ltd. and printed by Plaistow Press Magazines Ltd. -

Salome Bey 1933-2020

September 2020 www.torontobluessociety.com Published by the TORONTO BLUES SOCIETY since 1985 [email protected] Vol 36, No 9 Salome Bey 1933-2020 CANADIAN PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT #40011871 Keeping Live Alive Blues Reviews Remembering Salome Top Blues Loose Blues News Blues Online TORONTO BLUES SOCIETY 910 Queen St. W. Ste. B04 Toronto, Canada M6J 1G6 Tel. (416) 538-3885 Toll-free 1-866-871-9457 Email: [email protected] Website: www.torontobluessociety.com MapleBlues is published monthly by the Toronto Blues Society ISSN 0827-0597 2020 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Derek Andrews (President), Janet Alilovic, Jon Arnold, Ron Clarkin (Treasurer), Lucie Dufault (Vice-President), Carol Flett (Secretary), Sarah French, Lori Murray, Ed Parsons, Jordan Safer, Paul Sanderson, Mike Smith, John Valenteyn (Executive) Musicians Advisory Council: Brian Blain, Alana Bridgewater, Jay Douglas, Ken Kawashima, Gary Kendall, Dan McKinnon, Lily Sazz, Mark Stafford, Dione Taylor, Julian Taylor, Jenie Thai, Suzie Vinnick,Ken Whiteley Volunteer & Membership Committee: Lucie Dufault, Rose Ker, Mike Smith, Ed Parsons, Carol Flett Grants Officer: Barbara Isherwood Office Manager: Hüma Üster Marketing & Social Media Manager: Meg McNabb Publisher/Editor-in-Chief: Derek Andrews Managing Editor: Brian Blain [email protected] Contributing Editors: John Valenteyn, Janet Alilovic, Hüma Üster, Carol Flett Listings Coordinator: Janet Alilovic Mailing and Distribution: Ed Parsons Advertising: Dougal Bichan Did you miss this year's awards show? Are you curious about the performances of the 23rd Maple Blues Awards [email protected] guest musicians at Koerner Hall? All 6 performances will be available on TBS Youtube Channel and we kicked For ad rates & specs call 416-645-0295 off this special video series with the recent JUNO Blues Album of the Year award winner Dawn Tyler Watson, and www.torontobluesociety.com/newsletters/ rate-card Matchedash Parish. -

Üddon's COSMOPOLITAN REVIEW Vol.L.No.L

üddon's COSMOPOLITAN REVIEW Vol.l.No.l. ^U April. 13.1965. THE BENEFITS MORAL AND SECULAR OF ASSASSINATION If authority success and eugenic usefulness can sanction homicide,then history records numerous murders which have fulfilled the expectations of their perpetrators,and the names of the assassins command the respect all who value statecraft,wisdom and courage; for they were the very pillars of all the most successful of older governments. Those most pleasant to live within and most high in achievement. In the best of these the strongest assassin was the king,for so long as his courage and administrative ability sustained his right to office, and degeneration or abuse of power was corrected by violent dethronement or assassination. The wiser public opinion of the ancient world every where approved of assassination as an instrument of political or racial improvement. Works of art abounded. Since that golden age,it must be confessed,the art has seen only retro gression almost unchecked. Occassionally some generation or isolated community,by an effort of intellectual emancipation has freed itself temporarily from the domination of the superstitious,the crafty and the stupid; but even in the brightest of these periods the clouds of false civilisation have blinded truly great assassins to the august nature of tlmrdmts, and they are found spoiling some of their own greatest strokes by paying lip-service to the tenets of the mystagogues. Nevertheless encouragement can be found for the hope of a truly universal renaissance (if only the pragmatic sanctions for this art can be made clear to the well-disposed and ins true ted.persons everywhere) in the recurrence,by force of necessity or through individual genius,of natural assassins throughout every generation,persisting even to our benighted day. -

Black Gospel Music and the Civil Rights Movement

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History Summer 8-12-2013 Sit In, Stand Up and Sing Out!: Black Gospel Music and the Civil Rights Movement Michael Castellini Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Recommended Citation Castellini, Michael, "Sit In, Stand Up and Sing Out!: Black Gospel Music and the Civil Rights Movement." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/76 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SIT IN, STAND UP AND SING OUT!: BLACK GOSPEL MUSIC AND THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT by MICHAEL CASTELLINI Under the Direction of Dr. John McMillian ABSTRACT This thesis explores the relationship between black gospel music and the African American freedom struggle of the post-WWII era. More specifically, it addresses the paradoxical suggestion that black gospel artists themselves were typically escapist, apathetic, and politically uninvolved—like the black church and black masses in general—despite the “classical” Southern movement music being largely gospel-based. This thesis argues that gospel was in fact a critical component of the civil rights movement. In ways open and veiled, black gospel music always spoke to the issue of freedom. Topics include: grassroots gospel communities; African American sacred song and coded resistance; black church culture and social action; freedom songs and local movements; socially conscious or activist gospel figures; gospel records with civil rights themes.