12 Silvia.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film in São Paulo

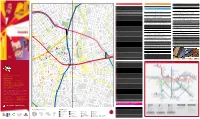

FILM IN SÃO PAULO Guidelines for your new scenario spcine.com.br [email protected] @spcine_ and @spfilmcommission /spcinesp PRODUCTION GUIDE 2020 1 2 FILM IN SÃO PAULO Guidelines for your new scenario PRODUCTION GUIDE 2020 Art direction and design: Eduardo Pignata Illustrations: Bicho Coletivo 3 4 CHAPTER 3 - FILMING IN SÃO PAULO _ P. 41 Partnership with Brazilian product company _ p. 43 CONTENT Current co-production treaties _ p. 44 Entering Brazil _ p. 45 Visa _ p. 46 ATA Carnet _ p. 51 Taxes _ p. 52 Remittance abroad taxes _ p. 53 IRRF (Withholding income tax) _ p. 53 Labour rights _ p. 54 CHAPTER 1 - SÃO PAULO _ P. 9 Workdays and days off _ p. 55 Offset time compensation _ p. 55 An introduction to São Paulo _ p. 11 Payment schedule _ p. 56 Big productions featuring São Paulo _ p. 17 Health & safety protocols _ p. 59 The Brazilian screening sector around the world _ p. 21 Filming infrastructure _ p. 61 São Paulo’s main events _ p. 23 Sound stages _ p. 62 São Paulo’s diversity _ p. 26 Equipment _ p. 62 Daily life in São Paulo _ p. 65 Locations _ p. 66 Weather and sunlight _ p. 69 Safety & public security _ p. 70 Logistics _ p. 70 Airports _ p. 71 Guarulhos Airport _ p. 71 CHAPTER 2 - SPCINE _ P. 27 Congonhas Airport _ p. 72 Who we are _ p. 29 Viracopos Airport _ p. 72 Spcine _ p. 30 Ports _ p. -

Evaluating the Quality Standard of Oscar Freire Street Public Space, in São Paulo, Brazil

Journal of Multidisciplinary Engineering Science and Technology (JMEST) ISSN: 2458-9403 Vol. 3 Issue 4, April - 2016 Evaluating the quality standard of Oscar Freire Street public space, in São Paulo, Brazil Ana Maria Sala Minucci Dr. Roberto Righi Doctor‟s degree in Architecture at Mackenzie Architecture and Urbanism Full Professor at Presbyterian University – UPM Mackenzie Presbyterian University São Paulo - Brazil São Paulo - Brazil [email protected] [email protected] Abstract - This article evaluates the quality urbanization away from the floodplains of standard of Oscar Freire Street public space Tamanduateí and Tietê rivers and redirected it to the located in São Paulo, Brazil. In 2006, the street high and healthy lands located southwest of underwent the reconfiguration of the public space downtown [2]. Higienópolis District and Paulista consisting of five commercial blocks, through a Avenue, with new streets were formed according to public-private partnership. Twelve quality criteria, best urban standards. The importance of the elite proposed by Jan Gehl in his book "Cities for location for the establishment of local patterns of the People" related to comfort, safety and pedestrian most important activities in the city, in developing delight, were used to analyze the quality of the countries, is explained by the large share of public space. The study shows that the street participation of this social segment in the composition already met some urban quality criteria even of aggregate consumption demand and its political before the urban intervention and passed to meet importance in the location of private companies and other quality criteria, in addition to the previous public facilities [3]. -

Privatizing Urban Planning and the Struggle for Inclusive Urban Development: New Redevelopment Forms and Participatory Planning in São Paulo

Privatizing Urban Planning and the Struggle for Inclusive Urban Development: New Redevelopment Forms and Participatory Planning in São Paulo by Joshua Daniel Shake A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Urban and Regional Planning) in The University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor Martin J. Murray, Chair Associate Professor David S. Bieri, Virginia Tech University Assistant Professor Harley F. Etienne Clinical Professor Melvyn Levitsky Associate Professor Eduardo Cesar Leão Marques, University of São Paulo © Joshua Daniel Shake 2016 DEDICATION To my mother, who gave me my love for books, inspired my passion for travel, and always encouraged me to ask questions about the world around me. She may no longer be here with me, but I know I would not be where I am today without her guidance and love and that she continues to provide both. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Over the past four years, I have discovered that completing a Ph.D. is an odd mixture of personal dedication, determination, and desire, along with making sure you have the right people around you to provide guidance, help, and support along the way. While in the limited space here I cannot give due credit to all of those that contributed in some form to this endeavor, I do want to call attention to a few very important individuals without whom I would not have completed this undertaking. My first and largest thank you goes to my committee members: Martin Murray, Eduardo Marques, Harley Etienne, David Bieri, and Melvyn Levitsky. Their feedback and advice on research, academic, and non-academic issues will always be valued. -

Per Capita Mensal Em São Paulo Corresponde a R$ 48,40 Por Dia Rendimento Médio Per Capita Mensal*

Janeiro/2020 São Paulo diversa: uma análise a partir de regiões da cidade Sobre a Pesquisa Seade Objetivo: analisar atributos da população residente na Região Metropolitana de São Paulo e fenômenos no espaço urbano. Estrutura da pesquisa: • Questionário fixo: captação de atributos da população perfis demográfico e educacional, trabalho, renda e moradia • Questionário variável: temas específicos e relacionados a espaço urbano e políticas públicas mobilidade urbana; uso de aplicativo no trabalho; atividade física; acesso a informação Coleta de dados: aplicação de questionário em visita domiciliar, para todos os moradores. Público-alvo: população residente na Região Metropolitana de São Paulo. Amostra: 2.100 domicílios/mês. 1 Pesquisa Seade – Módulo Município de São Paulo Este módulo da pesquisa analisa aspectos da vida no município de São Paulo, com foco no território, buscando mostrar a diversidade entre as regiões de moradia e identificar padrões/diferenças. Aspectos analisados, por regiões de moradia: • características dos moradores; • oferta de serviços nas proximidades da moradia; • renda domiciliar; • deslocamento das pessoas no espaço urbano. Período de referência: 2º semestre de 2019. 2 Regiões do Município de São Paulo* 1) Centro Ampliado: • Zona Centro: distritos da Sé, Bela Vista, Bom Retiro, Cambuci, Consolação, Liberdade, República e Santa Cecília. Distribuição da população do Município de • Zona Oeste: distritos de Pinheiros, Alto de Pinheiros, Itaim São Paulo, por região Bibi, Jardim Paulista, Lapa, Perdizes, Vila Leopoldina, Em % Jaguaré, Jaguara, Barra Funda, Butantã, Morumbi, Raposo Tavares, Rio Pequeno e Vila Sônia. Centro Ampliado (2,67 milhões) • Zona Sul 1: distritos de Vila Mariana, Saúde, Moema, 21 23 Ipiranga, Cursino, Sacomã, Jabaquara e Campo Belo. -

Lista De Unidades Básicas De Saúde (UBS) De São Paulo

Lista de unidades básicas de saúde (UBS) de São Paulo CENTRO Bela Vista UBS HUMAITÁ - DR. JOÃO DE AZEVEDO LAGE R. HUMAITÁ, 520 - BELA VISTA CEP: 01321-010 - FONE: 3241-1632 / 3241-1163U UBS NOSSA SENHORA DO BRASIL - ARMANDO D'ARIENZO R. ALM. MARQUES LEÃO, 684 - MORRO DOS INGLESES CEP: 01330-010 - FONE: 3284-4601 / FAX: 3541-3704 Bom Retiro UBS BOM RETIRO - DR. OCTAVIO AUGUSTO RODOVALHO R. TENENTE PENA, 8 - BOM RETIRO CEP: 01127-020 - FONE: 3222-0619 / 3224-9903 Cambuci UBS CAMBUCI AV. LACERDA FRANCO, 791 - CAMBUCI CEP: 01536-000 - FONE: 3276-6480 / 3209-3304 República UBS REPÚBLICA PRAÇA DA BANDEIRA, 15 - REPÚBLICA CEP: 01007-020 - FONE: 3101-0812 Santa Cecília UBS BORACEA R. BORACEA, 270 - SANTA CECÍLIA CEP: 01135-010 - FONE: 3392-1281 / 3392-1882 UBS SANTA CECÍLIA - DR. HUMBERTO PASCALE R. VITORINO CARMILO, 599 - CAMPOS ELISEOS CEP: 01153-000 - FONE: 3826-0096 / 3826-7970 Sé UBS SÉ R. FREDERICO ALVARENGA, 259 - PQ. D. PEDRO II CEP: 01020-030 - FONE: 3101-8841 / 3101-8833 ZONA LESTE Água Rasa UBS ÁGUA RASA R. SERRA DE JAIRE, 1480 - ÁGUA RASA CEP: 03175-001 - FONE: 2605-2156 / 2605-5307 / FAX: 2605-0644 UBS VILA BERTIOGA - PROF. DOMINGOS DELASCIO R. FAROL PAULISTANO, 410 - ALTO DA MOOCA CEP: 03192-060 - FONE: 2965-1066 / 2021-7210 UBS VILA ORATÓRIO - DR. TITO PEDRO MASCELANI R. JOÃO FIALHO DE CARVALHO, 35 - V. DIVA CEP: 03345-010 - FONE: 2301-2979 / FAX: 2910-3204 Aricanduva UBS JARDIM IVA R. MIGUEL BASTOS SOARES, 55 - JD. IVA CEP: 03910-000 - FONE: 2211-0884 / FAX: 2911-1006 UBS VILA ANTONIETA R. -

CENTRO E BOM RETIRO IMPERDÍVEIS Banco Do Brasil Cultural Center Liberdade Square and Market Doze Edifícios E Espaços Históricos Compõem O Museu

R. Visc onde de T 1 2 3 4 5 6 aunay R. Gen. Flor . Tiradentes R. David Bigio v R. Paulino A 27 R. Barra do Tibaji Av C6 R. Rodolf Guimarães R. Par . Bom Jar Fashion Shopping Brás o Miranda Atrativos / Attractions Monumentos / Monuments es dal dim A 28 v B2 Fashion Center Luz . R. Mamor R. T C é r R. Borac é u R. Pedro Vicente 29 almud Thorá z Ferramentas, máquinas e artigos em borracha / eal e 1 1 i Academia Paulista de Letras C1 E3 “Apóstolo Paulo”, “Garatuja, “Marco Zero”, entre outros R. Mamor r e R. Sólon o R. R R. do Bosque d C3 Tools, machinery and rubber articles - Rua Florêncio de Abreu éia ARMÊNIA odovalho da Fonseca . Santos Dumont o 2 R. Gurantã R. do Ar D3 v Banco de São Paulo Vieira o S A R. Padr R. Luis Pachec u 30 l ecida 3 Fotografia / Photography - Rua Conselheiro Crispiniano D2 R. Con. Vic Batalhão Tobias de Aguiar B3 ente Miguel Marino R. Vitor R. Apar Comércio / Shopping 31 Grandes magazines de artigos para festas Air R. das Olarias R. Imbaúba 4 R. Salvador L osa Biblioteca Mário de Andrade D2 R. da Graça eme e brinquedos (atacado e varejo) / Large stores of party items and toys 5 BM&F Bovespa D3 A ena R. Araguaia en. P eição R. Cachoeira 1 R. Luigi Grego Murtinho (wholesale and retail) - Rua Barão de Duprat C4 R. T R. Joaquim 6 Acessórios automotivos / Automotive Accessories R. Anhaia R. Guarani R. Bandeirantes Caixa Cultural D3 apajós R. -

Mapa Da Desigualdade De 2019, Pela Primeira Vez, Foram Elencados Todos Os Distritos Empatados Como Piores E Melhores Em Cada Indicador

Mapa da desigualdade ublicado desde 2012, o trabalho consiste no levantamento de uma série de indicadores de cada um dos 96 distritos da capital, de modo que se possa comparar dados e verificar os locais mais desprovidos de Pserviços e equipamentos públicos. Em muitos casos, a enorme distância entre o melhor e o pior indicador – que determina o “Desigualtômetro” que aparece nas páginas de cada tema – dá uma boa dimensão dos desafios que precisam ser superados. Dessa forma, este mapa ajuda os gestores municipais a identificar prioridades e necessidades da população e seus distritos. Ao contribuir para o entendimento de dinâmicas importantes da cidade, também se coloca como um instrumento para a elaboração de políticas públicas mais inclusivas e a construção de planos setoriais mais integrados. No mais, o Mapa da Desigualdade preenche uma lacuna em termos de difusão de informações O que é públicas, amplia o alcance do conhecimento sobre os territórios e facilita a o Mapa da assimilação dos dados disponíveis. Desigualdade Em um município em que milhões de pessoas são separadas pelo acesso (ou a falta dele) a bens e serviços públicos fundamentais, colocar em evidência os dados oficiais e disponíveis é apenas o primeiro passo para que tenhamos uma cidade à altura de sua importância para o país e, principalmente, que ofereça qualidade de vida para todos os seus habitantes. Um lugar sem extremos tão distantes em termos socioeconômicos, mais acolhedor para os moradores e integralmente reconhecido pelo próprio poder público. Lançado Traz dados -

Títulos Principais Em Arial 12 Negrito

Innovation is ViaQuatro’s trademark for São Paulo’s urban mobility Subway Line 4 (Yellow) offers unprecedented technologies to its passengers Responsible for the operation and maintenance of Line 4 (Yellow) of the São Paulo subway, ViaQuatro invests in innovations exclusively designed to transport passengers in a safe, fast and comfortable way. Its technological edge ranges from platform doors to the driverless system, timers that show when the train will arrive at the station and a display that shows the number of people in each car. Line 4 (Yellow) trains are equipped with the most modern subway technology, which combines radio CBTC (Communications-based train control) and driverless operation (no conductors). This system prevents human errors and controls both train speed and intervals, as necessary. It also controls the number of trips, door opening times and the number of trains in the line based on passenger demand. Line 4 (Yellow) trains have air conditioning, free passage between the cars, mobile phone signal, low noise level, energy efficient lighting and direct communication with the Operation Control Center (CCO). CCTV cameras follow movements in real time throughout the line, inside the trains, in the stations and in the parking and maintenance yards. The fleet, composed of 29 trains, carries 750,000 passengers per business day, in 951 trips. The stations are also modern and comfortable. Line 4 (Yellow) was the first line in Latin America to install glass panel doors that separate the platform from the rails. The platform doors open at the same time as the train doors and trains stop exactly where users get on and off, helping reduce the number of accidents and interruptions in the subway. -

Public Spaces, Stigmatization and Media Discourses of Graffiti Practices in the Latin American Press: Dynamics of Symbolic Exclusion and Inclusion of Urban Youth

Public spaces, stigmatization and media discourses of graffiti practices in the Latin American press: Dynamics of symbolic exclusion and inclusion of urban youth Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Soziologie am Fachbereich Politik- und Sozialwissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Alexander Araya López Berlin, 2015 Erstergutachter: Prof. Dr. Sérgio Costa Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Fraya Frehse Tag der Disputation: 10 Juli, 2014 2 Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... 5 Abstract ............................................................................................................................. 7 Zusammenfassung ............................................................................................................ 8 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 9 Do cities still belong to us? ........................................................................................... 9 Chapter I ......................................................................................................................... 14 Youth: A social construction of otherness .................................................................. 14 Graffiti as social practice......................................................................................... 24 Chapter II ....................................................................................................................... -

Relação Dos Bairros Abrangidos Pela Competência Territorial Da Vara De Violência Doméstica Norte (Santana)

RELAÇÃO DOS BAIRROS ABRANGIDOS PELA COMPETÊNCIA TERRITORIAL DA VARA DE VIOLÊNCIA DOMÉSTICA NORTE (SANTANA) ÁGUA FRIA JARDIM PAULISTANO VILA ESPANHOLA BAIRRO DO LIMÃO JARDIM PEREIRA LEITE VILA ESTER BORTOLÂNDIA JARDIM PERI VILA FERRÃO BRASILÂNDIA JARDIM PERI NOVO VILA FERRUCIO CACHOEIRINHA JARDIM PICOLO VILA FIDALGO CAMPO DA ÁGUA BRANCA JARDIM PIRITUBA VILA FLORENTINA CAMPO LIMPO JARDIM PRINCESA VILA FRANCISCO MENTEM CANTAREIRA JARDIM RECANTO VILA GENIOLI CARANDIRU JARDIM REGINA VILA GERMINAL CASA VERDE JARDIM RINCÃO VILA GONÇALVES CASA VERDE ALTA JARDIM RINCÃO VILA GOUVEIA CASA VERDE BAIXA JARDIM SANTA CRUZ VILA GUILHERME CASA VERDE MÉDIA JARDIM SANTA INÊS VILA GUSTAVO CHÁCARA CUOCO JARDIM SANTA MARCELINA VILA HEBE CHÁCARA DO ENCOSTO JARDIM SANTA MARIA VILA HERMINIA CHÁCARA DO ROSÁRIO JARDIM SÃO BENTO VILA HERMINIA LOPES CHÁCARA INGLESA JARDIM SÃO DOMINGOS VILA IARA CHÁCARA MORRO ALTO JARDIM SÃO JOÃO VILA ICARAI CHÁCARA PARQUE DAS NAÇÕES II JARDIM SÃO JORGE VILA IORIO CHÁCARA SÃO JOSÉ JARDIM SÃO JOSÉ VILA IRMÃOS ARNONI CHORA MENINO JARDIM SÃO LUIS VILA ISABEL CIDADE D'ABRIL JARDIM SÃO MANOEL VILA ISMÊNIA CIDADE DÁBRIL (GLEBA 2) JARDIM SÃO MARCOS VILA ISOLINA CITY RECANTO ANASTÁCIO JARDIM SÃO MIGUEL VILA ISOLINA MAZZEI CONJUNTO FIDALGO JARDIM SÃO PAULO VILA ITABERABA CONJUNTO RES. PARQUE DO JARAGUÁ JARDIM SÃO RICARDO VILA JARDIM ZOOLÓGICO ESTÂNCIA JARAGUÁ JARDIM SHANGRILÁ VILA JOSE CASA GRANDE FREGUESIA DO Ó JARDIM SIDNEY VILA JULIO CESAR FURNAS JARDIM SONIA VILA LAURA GUAPIRA JARDIM TABOR VILA LEONOR HORTO FLORESTAL JARDIM TAIPAS VILA LIDERANÇA IMIRIM JARDIM TERESA VILA MANOEL LOPES ITABERABA JARDIM VIEIRA DE CARVALHO VILA MARIA JAÇANÃ JARDIM VIRGINIA BIANCA VILA MARIA ALTA JARAGUÁ JARDIM VISTA ALEGRE VILA MARIA AUGUSTA JARDIM ADELIA JARDIM VITÓRIA VILA MARIA BAIXA JARDIM ALIANÇA JARDIM VIVIAN VILA MARIA TRINDADE JARDIM ALMANARA JARDIM YARA VILA MARIETA JARDIM ALTO DE TAIPAS LAUZANE PAULISTA VILA MARILU JARDIM ALVINA LIMÃO VILA MARINA JARDIM ALVORADA MANDAQUI VILA MARIZA MAZZEI JARDIM ANA MARIA MOINHO VELHO VILA MATIAS JARDIM ANAGILDA NOSSA SRA. -

IN NUMBERS GASTRONOMY NIGHTLIFE HEALTH and WELLNESS 12 Million Inhabitants in the City, a City of Aromas and Flavors

Caio Pimenta © Skol Sensation © José Cordeiro Sensation Skol Ibirapuera Park © José Cordeiro Zucco Restaurant © José Cordeiro Restaurant Zucco Open Air Urban Art Museum IN NUMBERS GASTRONOMY NIGHTLIFE HEALTH AND WELLNESS 12 million inhabitants in the city, A city of aromas and flavors. São Paulo has gastronomy as one of the strongest cultural traits. The offer The São Paulo’s nightlife is a truly portrait of the city: frenetic, creative, diverse and democratic. São Paulo, by + than 15 million tourists per year. or 21 million in the metropolitan region. has excellence and is democratic. Whether for a business lunch, friends reunion or a family meeting, there the way, is famous for its nightlife that has already been awarded among the bests like Ibiza and New York. To have the most important hospital and the best health professionals of the Country is a privilege of the biggest Brazilian are always options that goes from the popular gastronomy to the renowned restaurants. A fresh sashimi, Around all the corners, lively happy hours start the party: residents and tourists mingle to dance, flirt, eat, metropolis, destination of so many people that look for excelence in hospitals and state-of-the-art laboratories with a crunchy samosa, a properly spicy ceviche and a surprising fresh pasta are some of the delights at the drink or all those things at the same time. There are some whole neighborhoods dedicated to provide hours advanced technology to diagnose and treat the most complex diseases, with an excellent cost-benefit ratio compared 30.000 109 parks and capital; and we didn’t mention yet the feijoada, the virado à paulista, the really giant codfish pastry and the of fun. -

Material and Cultural Politics of Housing in São Paulo, 1950-1995

Architectures of the People: Material and Cultural Politics of Housing in São Paulo, 1950-1995 by José Henrique Bortoluci A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in The University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor George P. Steinmetz, Chair Associate Professor Matthew Hull Assistant Professor Robert S. Jansen Associate Professor Greta R. Krippner Associate Professor Claire A. Zimmerman © José Henrique Bortoluci 2016 All archaeology of matter is an archaeology of humanity. What this clay hides and shows is the passage of a being through time and space, the marks left by fingers, the scratches left by fingernails, the ashes and the charred logs of burned-out bonfires, our bones and those of others, the endlessly bifurcating paths disappearing off into the distance and merging with each other. José Saramago, The cave, p. 66. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS From the moment I began to cultivate the initial ideas for this dissertation on the house as a political and cultural assemblage, I have lived in at least eleven houses in two different cities. These cities could not be more dissimilar: the São Paulo of movement, concrete, traffic, the continuous sensorial excitement that inspires (if it does not drive you mad), and scandalous inequality and the Ann Arbor of cafés and libraries, long and cold winters, running tracks by the river, and a soothing yet sometimes annoying and artificial calm (do not forget Detroit is around the corner). My experience of these two cities, colored by visits to Jaú and Rio de Janeiro whenever possible, are the background and the material of this dissertation.