Arabikenari Mohammadali 202

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

№3 2015 Bahram Moghaddas, Mahdieh Boostani НААУЧНЫИ the INFLUENCE OFRUMI’S THOUGHT РЕЗУЛЬТАТ on WHITMAN’S POETRY Сетевой Научно-Практический Журн

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE providedа by DSpace у ч at Belgorod н ы State й University р е з у л ь т а т UDC 821 DOI: 10.18413 / 2313-8912-2015-1-3-73-82 Bahram Moghaddas PhD in TEFL, Ministry of Education, Mahmoodabad, Mazandaran, Iran Department of English, Khazar Institute of Higher Education, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Mahdieh Boostani PhD Candidate in the English Language and Literature, Banaras Hindu University, India E-mail: [email protected] Ab STRACT ufism or tasaw w uf is the inner, mystical, or psycho-spiritual dimension of Islam. SHowever, many scholars believe that Sufism is outside the sphere of Islam. As a result, there has always been disagreement among religious scholars and Sufis themselves regarding the origins of Sufism. The traditional view sees Sufism as the mystical school of Islam and its beginnings in the first centuries following the life of the Prophet Mohammad. Indeed, there is another view that traces the pre-Islamic roots of Sufism back through mystics and mystery schools of the other regions gathered into the trunk known as Islamic Sufism. The word Sufi originates from a Persian word meaning wisdom and wisdom is the ultimate power. The following survey tries to explore this concept in the works of Rumi and its impact on the western writers and poets particularly Whitman. It tries to show how Whitman inspired from Rumi and came to be the messenger of Sufism in his poems. These poems reveal the depth of Sufi spirituality, the inner states of mystical love, and the Unity of Being through symbolic expressions. -

"Flower" and "Bird" and the Related Mystical Literature

Science Arena Publications Specialty Journal of Humanities and Cultural Science Available online at www.sciarena.com 2017, Vol, 2 (2): 7-15 Study of "Flower" and "Bird" and the Related Mystical Literature hamideh samenikhah1, Ardeshir Salehpour2 1MA of art research, Department of Art and Architecture, Islamic Azad University, Tehran center Branch, Iran. Email: [email protected] 2PhD of art research, Department of Art and Architecture, Islamic Azad University, Tehran center Branch, Iran Abstract: In painting and scriptures, patterns and images transfer special meaning to the audience which are known as symbols. Understanding the concepts of such symbols forms a work. As it is known, there is a long- standing link between literature and art. Traditionally, poets or artists use symbols in literature and art to express their purposes. Since the images are the symbols of mystical concepts, it can be said that the painting is directly connected to mysticism. For example, in the paintings and scriptures of flower and bird, flower is the symbol of the beloved and bird is the symbol of lover. The romantic speeches between flower and bird are the symbol of God's praise. Flower and bird paintings are dedicated to Iranian art that refer to four thousand years ago, the companion of plant with bird is originated from the Phoenix myths and the tree of life. Interpretations of flowers and birds in nature are concerned by most poets. Flower and bird are used in the works of the poets, especially those who use the symbol for mystical concepts. The present research which is written in descriptive method aims to study "flower" and "bird" and the mystical literature related to these concepts. -

A Poet Builds a Nation.Pdf

DOI: 10.9744/kata.16.2.109-118 ISSN 1411-2639 (Print), ISSN 2302-6294 (Online) OPEN ACCESS http://kata.petra.ac.id A Poet Builds a Nation: Hafez as a Catalyst in Emerson’s Process of Developing American Literature Behnam Mirzababazadeh Fomeshi*, Adineh Khojastehpour Independent scholars * Corresponding author emails: [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT Numerous studies have tried to elucidate the relationship between Emerson and Hafez. While most of these studies laid emphasis on influence of Hafez on Emerson and others on similarity and/or infatuation, they left untouched some vital historical aspects of this relationship. Taking into consideration the political and literary discourses of Emerson‘s America may illuminate the issue. America‘s attempt to gain independence from Britain, Emerson‘s resolution to establish an American literary tradition, his break with the European fathers to establish that identity, his open-mindedness in receiving non-European cultures and the correspondence between Emerson‘s transcendentalism and Hafez‘s mysticism led to Hafez‘s reception by Emerson. Keywords: Hafez; Emerson; comparative literature; reception; national identity INTRODUCTION The relationship between Hafez and Emerson has been extensively studied. Most of the researchers In addition to being considered the father of trans- have highlighted influence and some have empha- cendentalism, the American poet and philosopher, sized similarity or infatuation. For instance, Fotouhi Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) was a remar- and Taebi (2012) believed that Emerson‘s poetic taste kable figure concerning Persian literature. The poet‘s made him study Persian poets and ―correspondence most fruitful years coincided with his careful study of between their mystical insight and his transcendental Persian poets. -

(PDF Format) the Booklet “Cultural Parameters of Iranian Musical

Cultural Parameters of Iranian Musical Expression Edited by Margaret Caton & Neil Siegel The Institute of Persian Performing Arts Cultural Parameters of Iranian Musical Expression Presented at the 1986 meetings of The Middle East Studies Association November, 1986 Margaret Caton Jean During Robyn Friend Thomas Reckord Neil Siegel Mortezâ Varzi Edited by Margaret Caton & Neil Siegel Published by: The Institute of Persian Performing Arts 38 Cinnamon Lane Rancho Palos Verdes, California 90275 Copyright (c) 1986 / 1988 by the authors and The Institute of Persian Performing Arts (IPPA). All Rights Reserved. Re-formatted 2002 Table of Contents 1. Performer-Audience Relationships in the Bazm. Mortezâ Varzi; assisted by Margaret Caton, Robyn C. Friend, and Neil Siegel . .....1 2. Contemporary Contexts for Iranian Professional Musical Performance. Robyn C. Friend and Neil G. Siegel . ......8 3. Melodic Contour in Persian Music, and its Connection to Poetic Form and Meaning. Margaret Caton . .....15 4. The Role of Religious Chant in the Definition of the Iranian Aesthetic. Thomas Reckord . 23 5. Emotion and Trance: Musical Exorcism in Baluchistan. Jean During . 31 Performer-Audience Relationships in the Bazm Mortezâ Varzi Assisted by Margaret Caton, Robyn C. Friend, and Neil Siegel The Institute of Persian Performing Arts Presented at the 1986 meetings of The Middle East Studies Association November, 1986 Abstract: The bazm is an intimate party at which refreshment and musical entertainment are provided. The role of the musical performer at the bazm is to establish a rapport that provides the proper environment for musical performance by means of an emotional and spiritual connection with the audience. -

Cinema of Immanence: Mystical Philosophy in Experimental Media

CINEMA OF IMMANENCE: MYSTICAL PHILOSOPHY IN EXPERIMENTAL MEDIA By Mansoor Behnam A thesis submitted to the Cultural Studies Program In conformity with the requirements for The degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (May 2015) Copyright © Mansoor Behnam, 2015 Abstract This research-creation discovers the connection between what Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari termed as the Univocity of Being, and the Sufi and pantheistic concept of Unity of Being (wahdat al-wujud) founded by the Islamic philosopher/mystic Ibn al-‘Arabī(A.H. 560- 638/A.D. 1165-1240). I use the decolonizing historiography of the concept of univocity of being carried out by the scholar of Media Art, and Islamic Thoughts Laura U. Marks. According to Marks’ historiography, it was the Persian Muslim Polymath Abu ‘Ali al-Husayn ibn Sînâ (980-1037) who first initiated the concept of haecceity (thisness)--the basis of the univocity of being. The thesis examines transformative experimental cinema and video art from a mystical philosophical perspective (Sufism), and by defying binaries of East/West, it moves beyond naïve cosmopolitanism, to nuanced understanding of themes such as presence, proximity, self, transcendence, immanence, and becoming, in media arts. The thesis tackles the problem of Islamic aniconism, nonrepresentability, and inexpressibility of the ineffable; as it is reflected in the mystical/paradoxical concept of the mystical Third Script (or the Unreadable Script) suggested by Shams-i-Tabrīzī (1185- 1248), the spiritual master of Mawlana Jalal ad-Dīn Muhhammad Rūmī (1207-1273). I argue that the Third Script provides a platform for the investigation of the implications of the language, silence, unsayable, and non-representation. -

Journal of American Science 2013;9(11S)

Journal of American Science 2013;9(11s) http://www.jofamericanscience.org The Role of Molana Yaghoob Charcki In The Cevelopment of Persianliteratuer and Language Search and Authorship: Nader Karimian Sardashti, Ali Ahmadalizadeh The Faculty of Tourism, Handicraft, Cultural Heritage of Search in statute, Tehran, Iran Research Organization and Curriculum Development, Ministry of Education, Tehran, Iran [email protected] Abstract: Iran,s Literature History, and Also Language and Persian Literature on Its Path of own Evolution, Has Passed of Several Stages. This Scientific and Cultural movement at Global Literature Level in Iran and Islamic Worl, Majority of it Has Begun With Sufism,s Literature, Which in the next centuries could Display the most Brilliant cultural aspects of Persian and Iranian Literature. After forming sufi order and Mysticism, Which are the famous dynasty, Sufism,s Literature in Persian language found an especial place. Since, The Grand and Famous danstyes of world Sufism and mysticism like “Sohrevardieh”, “Kebroieh”, “Ghaderieh”, “Naghsbandieh”, “Molavieh”, “Cheshtieh”, “Norbakhshieh”, “Zahabieh”, and “Nematholahieh” are Established in culturl Iran, or Their founders and Remarkable Characters have been Iranian and Persian language, After a few centuries of Islamic civilization and Sufism,s exaltation by persons as “Bayazid”, “Bastami”, “Abolhassan kharghant”, “Abosaied Abolkhier”, “Abolghasem ghashiri”, “Khajeh abdollah ansari”, “Aboleshagh kazerony”, and “Ahmad Jam”, “Sanaie”, “Atar”, “Emam Ghazali”, “Shiekh Ahmad -

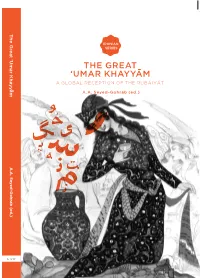

The Great 'Umar Khayyam

The Great ‘Umar Khayyam Great The IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES The Rubáiyát by the Persian poet ‘Umar Khayyam (1048-1131) have been used in contemporary Iran as resistance literature, symbolizing the THE GREAT secularist voice in cultural debates. While Islamic fundamentalists criticize ‘UMAR KHAYYAM Khayyam as an atheist and materialist philosopher who questions God’s creation and the promise of reward or punishment in the hereafter, some A GLOBAL RECEPTION OF THE RUBÁIYÁT secularist intellectuals regard him as an example of a scientist who scrutinizes the mysteries of the universe. Others see him as a spiritual A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) master, a Sufi, who guides people to the truth. This remarkable volume collects eighteen essays on the history of the reception of ‘Umar Khayyam in various literary traditions, exploring how his philosophy of doubt, carpe diem, hedonism, and in vino veritas has inspired generations of poets, novelists, painters, musicians, calligraphers and filmmakers. ‘This is a volume which anybody interested in the field of Persian Studies, or in a study of ‘Umar Khayyam and also Edward Fitzgerald, will welcome with much satisfaction!’ Christine Van Ruymbeke, University of Cambridge Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab is Associate Professor of Persian Literature and Culture at Leiden University. A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) A.A. Seyed-Gohrab WWW.LUP.NL 9 789087 281571 LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS The Great <Umar Khayyæm Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. -

Breaking Down Borders and Bridging Barriers: Iranian Taziyeh Theatre

Breaking Down Borders and Bridging Barriers: Iranian Taziyeh Theatre Khosrow Shahriari A thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Media, Film and Theatre University of New South Wales July 2006 ABSTRACT In the twentieth century, Western theatre practitioners, aware of the gap between actor and spectator and the barrier between the stage and the auditorium, experimented with ways to bridge this gap and cross barriers, which in the western theatrical tradition have been ignored over the centuries. Stanislavski, Meyerhold, Piscator, Brecht, Grotowski, and more recently Peter Brook are only a few of the figures who tried to engage spectators and enable them to participate more fully in the play. Yet in Iran there has existed for over three centuries a form of theatre which, thanks to its unique method of approaching reality, creates precise moments in which the worlds of the actor and the spectator come together in perfect unity. It is called ‘taziyeh’, and the aim of this thesis is to offer a comprehensive account of this complex and sophisticated theatre. The thesis examines taziyeh through the accounts of eyewitnesses, and explores taziyeh’s method of acting, its form, concepts, the aims of each performance, its sources and origins, and the evolution of this Iranian phenomenon from its emergence in the tenth century. Developed from the philosophical point of view of Iranian mysticism on the one hand, and annual mourning ceremonies with ancient roots on the other, taziyeh has been performed by hundreds of different professional groups for more than three hundred years. -

Sufism and American Literary Masters

Introduction For centuries, the Western fascination with the East has been the subject of countless books, plays, and movies, particularly after the economic and intellec- tual effects of colonialism in the early nineteenth century introduced “Oriental” cultures to a sophisticated drawing-room audience. However, Hafiz, Sa‘di, Jami, Rumi, and other Sufi masters had a place, however obscure and inaccurately portrayed, in the corpus of English translations long before Oriental themes and settings became a popular characteristic of nineteenth-century poetry. In fact, Sufi poetry was available to a European audience as early as the sixteenth cen- tury: the earliest reference to Persian poetry occurred in English in 1589, when George Puttenham included four anonymous “Oriental” poems in translation in The Arte of English Poesie; translations of Sa‘di’s Gulistan were available in Latin as early as 1654’s Rosarium, translated by the Dutch orientalist Georgius Gentius. From the early seventeenth century onward, Western interest in Persian and Sufi poetry steadily increased, though such interest most often took the form of general references to Persian language and culture and not to specific poets and their works. Such references were already a standard component of the medieval travel narrative, and almost always misidentified the names of Iranian and Arab poets, mystics, and philosophers, accompanied by equally creative spelling varia- tions. Moreover, there was no literary value attached to literal translations, and no effort made to replicate the formal elements of the original poems. Instead, Sufi poetry entered Western literary circles as versified adaptations or imitations. Sa‘di’s Gulistan, Hafiz’s Divan, Omar Khayyam’s Ruba‘iyyat, as well as Firdawsi’s monumental work of Persian epic Shah Nameh, were all available to English audiences in some form by 1790. -

Mysticism of American Transcendentalism in Emerson's

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 9, No. 11, pp. 1442-1448, November 2019 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0911.10 Evokers of the Divine Message: Mysticism of American Transcendentalism in Emerson’s “Nature” and the Mystic Thought in Rumi’s Masnavi Amirali Ansari English Department, Yazd University, Yazd, Iran Hossein Jahantigh English Department, Yazd University, Yazd, Iran Abstract—Mysticism, religion and mankind’s relationship with an all-absolute deity has been a prominent part of the human experience throughout history. Poets such as Emerson and Rumi were similarly concerned with this question in creating their works. Although Rumi’s thought stems from the Quran and Emerson’s manifestation of Nature takes roots in the ancient eastern philosophies such as Buddhism, their works seem to share some explicit characteristics. Rumi (1207-1273) lived most of his life in Konya and Khorasan and Emerson (1803-1882) lived in America, but their immense geographic and temporal distances did not surpass their analogous attitudes as mystics. The biggest and the most obvious affinity between these mystic thoughts is believing in Monism as a spiritual practice. Although Emerson read and was influenced by classical Persian poetry of Hafiz and Sa’di, there is no evidence suggesting that he was familiar with Rumi’s poetry. Moreover, thematic analogies between Rumi’s Masnavi and Emerson’s essay on Nature result in a shared ideology which includes themes varying from monism, kashf or unveiling, attitudes towards language and the uninitiated. These concepts, observed in both works, point us toward the realization of universal features of mysticism. -

The Influence of Persian Language and Literature on Arab Culture

International Journal of Educational Research and Technology Volume 2, Issue 2, December 2011: 80 - 86 ISSN 0976-4089 Journal’s URL: www.soeagra.com/ijert.htm Original Article The Influence of Persian Language and Literature on Arab Culture Mohammad Khosravi Shakib Department of Persian Language and Literature, Human Science Faculty, Lorestan University, I. R. Iran. E- Mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT With the rise of Persian influence, the roughness of Arab life was softened and there opened an era of culture, toleration, and scientific research. The practice of oral tradition was also giving place to recorded statement and historical narrative, a change hastened by the scholarly tendencies introduced from the East. INTRODUCTION In the early days of the Prophet’s mission, there were only seventeen men in the tribe of Quraysh, who could read or write. (Professor Edward Browne, 2002). It is said that Mo’allaqat, the seven Arabic poems written in pre-Mohammedan times and inscribed in gold on rolls of coptic cloth and hung up on the curtains covering the Ka’aba were selected by the Iranian Hammad who seeing how little the Arabs cared for poetry urged them to study the poems. In this period, Hammad knew more than any one else about the Arabic poetry. Before the advent of Islam, the Arabs had a negligible literature and scant poetry. It was the Iranians who after their conversion to Islam, feeling the need to learn the language of the Qur’an, began to use that language for other purposes. The knowledge of Arabic was essential and indispensable for religious worship, and the correct reading of the Qur’an was impossible without it. -

Politics, Poetry and Sufism in Medieval Iran. New Perspectives on Jami's Salaman Va Absal by Chad Lingwood.Pdf

Politics, Poetry, and Sufism in Medieval Iran Studies in Persian Cultural History Editors Charles Melville Cambridge University Gabrielle van den Berg Leiden University Sunil Sharma Boston University VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/spch Politics, Poetry, and Sufism in Medieval Iran New Perspectives on Jāmī’s Salāmān va Absāl By Chad G. Lingwood LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 Cover illustration: Salāmān and Absāl arrive at the island of delight. Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.: Purchase, F1946.12.194 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lingwood, Chad G. Politics, poetry, and sufism in medieval Iran : new perspectives on Jami's Salaman va Absal / by Chad G. Lingwood. pages cm -— (Studies in Persian cultural history ; v. 5) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25404-6 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-25589-0 (e-book : alk. paper) 1. Jami, 1414–1492. Salaman va Absal. 2. Sufism—Iran—History. 3. Politics and literature—Iran. 4. Iran—History—1256–1500. I. Title. PK6490.S33L56 2013 891'.5512—dc23 2013031794 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 2210-3554 ISBN 978-90-04-25404-6 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25589-0 (e-book) Copyright 2014 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.