Iqbal and Sufism Sakina Khan∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hindi and Urdu*

saadat hasan manto Hindi and Urdu* The hindi-urdu dispute has been raging for some time now. Maulvi Abdul Haq Sahib, Dr. Tara Singh, and Mahatma Gandhi know what there is to know about this dispute. For me, though, it has so far remained incomprehensible. Try as hard as I might, I just havenít been able to understand. Why are Hindus wasting their time supporting Hindi, and why are Muslims so beside themselves over the preservation of Urdu? A language is not made, it makes itself. And no amount of human effort can ever kill a language. When I tried to write something about this current hot issue, I ended up with the following conversation: munshi narain parshad: Iqbal Sahib, are you going to drink this soda water? mirza muhammad iqbal: Yes, I am. munshi: Why donít you drink lemon? iqbal: No particular reason. I just like soda water. At our house, everyone likes to drink it. munshi: In other words, you hate lemon. iqbal: Oh, not at all. Why would I hate it, Munshi Narain Parshad? Since everyone at home drinks soda water, Iíve sort of grown accustomed to it. Thatís all. But if you ask me, actually lemon tastes better than plain soda. munshi: Thatís precisely why I was surprised that you would prefer something salty over something sweet. And lemon isnít just sweet, it has a nice flavor. What do you think? * ìHindī aur Urdū,î ManÅo-Numā (Lahore: Sañg-e Mīl Publications, 1991), 560– 63. 205 206 • The Annual of Urdu Studies, No. 25 iqbal: Youíre absolutely right. -

№3 2015 Bahram Moghaddas, Mahdieh Boostani НААУЧНЫИ the INFLUENCE OFRUMI’S THOUGHT РЕЗУЛЬТАТ on WHITMAN’S POETRY Сетевой Научно-Практический Журн

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE providedа by DSpace у ч at Belgorod н ы State й University р е з у л ь т а т UDC 821 DOI: 10.18413 / 2313-8912-2015-1-3-73-82 Bahram Moghaddas PhD in TEFL, Ministry of Education, Mahmoodabad, Mazandaran, Iran Department of English, Khazar Institute of Higher Education, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Mahdieh Boostani PhD Candidate in the English Language and Literature, Banaras Hindu University, India E-mail: [email protected] Ab STRACT ufism or tasaw w uf is the inner, mystical, or psycho-spiritual dimension of Islam. SHowever, many scholars believe that Sufism is outside the sphere of Islam. As a result, there has always been disagreement among religious scholars and Sufis themselves regarding the origins of Sufism. The traditional view sees Sufism as the mystical school of Islam and its beginnings in the first centuries following the life of the Prophet Mohammad. Indeed, there is another view that traces the pre-Islamic roots of Sufism back through mystics and mystery schools of the other regions gathered into the trunk known as Islamic Sufism. The word Sufi originates from a Persian word meaning wisdom and wisdom is the ultimate power. The following survey tries to explore this concept in the works of Rumi and its impact on the western writers and poets particularly Whitman. It tries to show how Whitman inspired from Rumi and came to be the messenger of Sufism in his poems. These poems reveal the depth of Sufi spirituality, the inner states of mystical love, and the Unity of Being through symbolic expressions. -

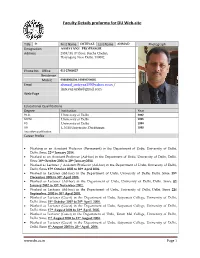

Faculty Details Proforma for DU Web-Site

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site Title Dr. First Name IMTEYAZ Last Name AHMAD Photograph Designation ASSISTANT PROFESSOR Address 2839/40, 4th floor, Kucha Chelan, Daryaganj, New Delhi. 110002. Phone No Office 011-27666627 Residence Mobile 09868008294 / 09899754685 Email [email protected] / [email protected] Web-Page Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. University of Delhi 2002 M.Phil. University of Delhi 1996 PG University of Delhi 1994 UG L.N.M.University, Darbhanga 1990 Any other qualification Career Profile Working as an Assistant Professor (Permanent) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 22nd January 2014. Worked as an Assistant Professor (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 16th October 2006 to 20th January2014. Worked as Lecturer / Assistant Professor (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 17th October 2005 to 30th April 2006. Worked as Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 28th December 2004 to 30th April 2005. Worked as Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 8th January 2002 to 15th November 2002. Worked as Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 21st September. 2000 to 30th April 2001. Worked as Lecturer (Guest) in the Department of Urdu, Satyawati College, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 31st October 2007 to 20th April. 2008. Worked as Lecturer (Guest) in the Department of Urdu, Satyawati College, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 17th August 2004 to 23rd April. -

Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology

Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology Merit List Department of Arabic (Bachelors, Morning) 2020 Abdul Haq Campus S# Form No Name Father Percent 1 202764 RABIAA MUHAMMAD AMIN 91.18 2 202095 NOORULAIN MUHAMMAD RAFIQ 67.27 3 205559 NASIR HUSSAIN KHUDA YAR 61.69 4 206180 ATA UR REHMAN ZAKIR UR REHMAN 54.22 Note: This list is conditional (Subjected to approval of Prof. Dr. Muhammad Zahid Concern Department and Varification of Documents). (Director Admission) Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology Merit List Department of Education (B.Ed 2.5 Years) (Bachelors, Morning) 2020 Abdul Haq Campus S# Form No Name Father Percent 1 204745 BUSHRA SAMI MUHAMMAD SAMI 78.34 2 204747 RUBAB SAMI MUHAMMAD SAMI 78.21 3 206250 SYED HASSNAN SYED MUHAMMAD SHAH 69.70 4 207469 MUHAMMAD AFTAB SARWAR MUHAMMAD SARWAR MALIK 68.67 5 205695 ALTAF AHMED MUHAMMAD MUNSIF 66.68 6 206100 MUHAMMAD FAIZAN MUHAMMAD IMRAN 66.38 7 200210 RAFIA FAROOQ MUHAMMAD FAROOQ 65.13 8 203771 NIMRAH AFTAB AFTAB AHMED 62.42 9 206939 MARINA RIAZ AHMED 61.70 10 203927 NUSRAT JABEEN DEEN MUHAMMAD 61.50 11 207432 BISMA MUHAMMAD YOUSUF BALOCH 60.69 12 202584 SEHRISH MUHAMMAD RIAZ 60.10 13 206963 HAYAT KHATOON KORAI MAZHAR UL HAQUE 60.00 14 202094 HUMAIRA MUHAMMAD KHAN 57.20 15 206719 ABDUL SAMAD MUHAMMAD RIAZ 56.36 16 206127 NAZIA MUHAMMAD YOUNUS 56.25 Note: This list is conditional (Subjected to approval of Prof. Dr. Muhammad Zahid Concern Department and Varification of Documents). (Director Admission) Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology Merit List -

Age of Peace Goodword.Indd

The Age of Peace MAULANA WAHIDUDDIN KHAN THE AGE OF PEACE Peace is the only culture for both man and the universe MAULANA WAHIDUDDIN KHAN First published 2015 This book is copyright free Goodword Books A-21, Sector 4, Noida-201301, India Tel. +91 1204314871, Mob. +91 8588822674 Email: [email protected] www.goodwordbooks.com Goodword Books, Hyderabad Tel. +91 4023514757 Mob. +91 7032641415, +91 9448651644 Email: [email protected] Goodword Books, Chennai Tel. +91 4443524599 Mob. +91 9790853944, +91 9600105558 Email: [email protected] Islamic Vision Ltd. 434 Coventry Road, Small Heath Birmingham B10 0UG, U.K. Tel. 121-773-0137, Fax: 121-766-8577 e-mail: [email protected], www.islamicvision.co.uk IB Publisher Inc. 81 Bloomingdale Rd, Hicksville NY 11801, USA Tel. 516-933-1000 Fax: 516-933-1200 Toll Free: 1-888-560-3222 email: [email protected] www.ibpublisher.com Printed in India Contents Foreword 5 Peace for the Sake of Peace On Pacifism 10 Peace: the Summum Bonum 13 Peace and Justice 16 The Power of Peace 19 The Advent of the Age of Peace The Age of De-monopolization 24 Western Civilization 27 The Age of Alternatives 30 The Age of Civilization 34 The Journey to Civilization 37 Making a Friend out of an Enemy 40 The Non-Confrontational Methods for Peace The Creation Plan of the Creator 44 The Policy of Mutual Non-interference 47 The ‘Save Yourself’ Formula 50 The Policy of Delinking 53 The Power of Peace is Greater than the Power of Violence 56 The Examples Set by Two Prophets 59 An Institutionalized Buffer 62 The Experience -

The Muslim 500 2011

The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500The The Muslim � 2011 500———————�——————— THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS ———————�——————— � 2 011 � � THE 500 MOST � INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- The Muslim 500: The 500 Most Influential Muslims duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic 2011 (First Edition) or mechanic, inclding photocopying or recording or by any ISBN: 978-9975-428-37-2 information storage and retrieval system, without the prior · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily re- Chief Editor: Prof. S. Abdallah Schleifer flect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Researchers: Aftab Ahmed, Samir Ahmed, Zeinab Asfour, Photo of Abdul Hakim Murad provided courtesy of Aiysha Besim Bruncaj, Sulmaan Hanif, Lamya Al-Khraisha, and Malik. Mai Al-Khraisha Image Copyrights: #29 Bazuki Muhammad / Reuters (Page Designed & typeset by: Besim Bruncaj 75); #47 Wang zhou bj / AP (Page 84) Technical consultant: Simon Hart Calligraphy and ornaments throughout the book used courtesy of Irada (http://www.IradaArts.com). Special thanks to: Dr Joseph Lumbard, Amer Hamid, Sun- dus Kelani, Mohammad Husni Naghawai, and Basim Salim. English set in Garamond Premiere -

Hajji Din Mohammad Biography

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Hajji Din Mohammad Biography Hajji Din Mohammad, a former mujahedin fighter from the Khalis faction of Hezb-e Islami, became governor of the eastern province of Nangarhar after the assassination of his brother, Hajji Abdul Qadir, in July 2002. He is also the brother of slain commander Abdul Haq. He is currently serving as the provincial governor of Kabul Province. Hajji Din Mohammad’s great-grandfather, Wazir Arsala Khan, served as Foreign Minister of Afghanistan in 1869. One of Arsala Khan's descendents, Taj Mohammad Khan, was a general at the Battle of Maiwand where a British regiment was decimated by Afghan combatants. Another descendent, Abdul Jabbar Khan, was Afghanistan’s first ambassador to Russia. Hajji Din Mohammad’s father, Amanullah Khan Jabbarkhel, served as a district administer in various parts of the country. Two of his uncles, Mohammad Rafiq Khan Jabbarkhel and Hajji Zaman Khan Jabbarkhel, were members of the 7th session of the Afghan Parliament. Hajji Din Mohammad’s brothers Abdul Haq and Hajji Abdul Qadir were Mujahedin commanders who fought against the forces of the USSR during the Soviet Occupation of Afghanistan from 1980 through 1989. In 2001, Abdul Haq was captured and executed by the Taliban. Hajji Abdul Qadir served as a Governor of Nangarhar Province after the Soviet Occupation and was credited with maintaining peace in the province during the years of civil conflict that followed the Soviet withdrawal. Hajji Abdul Qadir served as a Vice President in the newly formed post-Taliban government of Hamid Karzai, but was assassinated by unknown assailants in 2002. -

From Jesus and God to Muhammad and Allah and Back Again Kenyan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Göteborgs universitets publikationer - e-publicering och e-arkiv From Jesus and God to Muhammad and Allah – and back again Kenyan Christian and Islamic religious education in the slums of Kibera Mikael Kindberg Termin : HT 2010 Kurs: RKS 310 Religionsvetenskap för blivande lärare fördjupningskurs 30 hp Nivå: Kandidat (examensarbete) Handledare: Kerstin von Brömssen & Göran Larsson Rapportnummer: HT10-1150-14 Abstract Level of examination: Bachelor's degree (thesis) Title: From Jesus and God to Muhammad and Allah, and back again – Kenyan Christian and Islamic religious education in Nairobi Author: Mikael Kindberg Term and year: Autumn 2010 Department: Department of Literature, History of Ideas and Religion Report Number: HT10-1150-14 Supervisors: Kerstin von Brömssen and Göran Larsson Key words: CRE, IRE, Kenya, Secondary school, religious education, This study focuses on Christian and Islamic religious education and was carried out as a Minor Field Study at a secondary school in the slums of Kibera, Nairobi, during September- December 2010. The overall purpose is to examine and compare how Christian and Islamic religious education is taught at the selected school. The following questions constitute the problem areas: How is the Kenyan curriculum and syllabi in CRE and IRE designed, and what is said about religious education? How are students taught in religious education at the selected school? What are the teachers saying about religious education as a subject? The study has an ethnographic methodological approach, using textual analysis of curriculum and syllabi, classroom observations and qualitative interviews with teachers in order to collect the material. -

The Anjuman-I Taraqqi-Yi Urdu, 1903-1971 Introduction

Andrew Amstutz AIPS Final Report December 31, 2013 Finding a Home for Urdu: The Anjuman-i Taraqqi-yi Urdu, 1903-1971 Introduction: ‘Our Muhajir Anjuman’1: In Karachi in 1953 the Anjuman-i Taraqqi-yi Urdu (Association for the Advancement for Urdu) held its golden jubilee. The Anjuman-i Taraqqi-yi Urdu (henceforth, the Anjuman) is the largest Urdu scholarly promotional association in South Asia. Originally founded in 1903 as part of the All-India Muslim Educational Conference associated with Aligarh University to counter Hindi advocates in North India, the Anjuman first shifted from Aligarh to Aurangabad (Deccan) under the patronage of the Hyderabad princely state in 1913, then to Delhi in 1938, and finally to Karachi in 1949 following the Partition of British India. Looking back on the fifty-year history of the Anjuman in 1953, the prominent historian Syed Hashmi Faridabadi placed the shift of “our muhajir Anjuman” from Delhi to Karachi in a longer history of Urdu migrations. He employed the term muhajir (immigrant), which is used for Indian Muslims who migrated to Pakistan, to describe the Anjuman. It is in turn a religiously significant term for those who moved with the Prophet Muhammad from Mecca to Medina. Hashmi went on to note that in terms of this migration to Karachi in 1947, “this was really a type of beginning such as what happened during the era when [the Anjuman] was shifted from Aligarh to Aurangabad [in 1913].”2 On the face of it, there seems to be little in common between the bureaucratic shift in 1913 of the Anjuman’s headquarters to Aurangabad, which was then a provincial outpost of the Hyderabad State, and the massive migration of Urdu-speaking Muslims in 1947 to Karachi, the first capitol of Pakistan, amidst the violence of Partition. -

Studying Muhammad Iqbal's Works in Azerbaijan

Studying Muhammad Iqbal’s Works in Azerbaijan 65 Studying Muhammad Iqbal’s Works in Azerbaijan Dr. Basira Azizaliyeva* Abstract Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938) was Pakistan‘s prominent poet, philosopher and Islamic scholar. His works are characterized by a number of essential features. Islam, love philosophy, perfect humans were expressed in unity, in Iqbal‘s worldview. Iqbal performed as an advocate of humanism, global peace and cordial relations between East and West based on peaceful and tolerant values. He awakened the Muslims‘ material-spiritual development in the 20th century. Having a special propensity for Sufism, the writer was enriched and inspired by the work of the great Turkic Sufi thinker and poet Mevlana Jalāl Ad Dīn Rūmī. Muhammad Iqbal acted as a poet, philosopher, lawyer and teacher. Illuminator and reformer M. Iqbal, who was politically active, also gave concept for the establishment of the state of Indian Muslims in north-western India. The human factor is the main subject of M. Iqbal's thinking. The poet-thinker perceived Islamic society, as well as human pride as the centrifugal force of the whole world, and considered creative and moral relations as an important factor in solving the problems of human society. The questions that Iqbal adopted on the social and philosophical thinking of the East and the West were also directed to this important problem. M. Iqbal spoke from the position of the Islamic religion and at the same time correctly assessed the role of Islam in the modern world, and also invited the Islamic world to develop science and education. This article highlights number of research studies accomplished in Azerbaijan on poetry and philosophical works of Muhammad Iqbal. -

"Flower" and "Bird" and the Related Mystical Literature

Science Arena Publications Specialty Journal of Humanities and Cultural Science Available online at www.sciarena.com 2017, Vol, 2 (2): 7-15 Study of "Flower" and "Bird" and the Related Mystical Literature hamideh samenikhah1, Ardeshir Salehpour2 1MA of art research, Department of Art and Architecture, Islamic Azad University, Tehran center Branch, Iran. Email: [email protected] 2PhD of art research, Department of Art and Architecture, Islamic Azad University, Tehran center Branch, Iran Abstract: In painting and scriptures, patterns and images transfer special meaning to the audience which are known as symbols. Understanding the concepts of such symbols forms a work. As it is known, there is a long- standing link between literature and art. Traditionally, poets or artists use symbols in literature and art to express their purposes. Since the images are the symbols of mystical concepts, it can be said that the painting is directly connected to mysticism. For example, in the paintings and scriptures of flower and bird, flower is the symbol of the beloved and bird is the symbol of lover. The romantic speeches between flower and bird are the symbol of God's praise. Flower and bird paintings are dedicated to Iranian art that refer to four thousand years ago, the companion of plant with bird is originated from the Phoenix myths and the tree of life. Interpretations of flowers and birds in nature are concerned by most poets. Flower and bird are used in the works of the poets, especially those who use the symbol for mystical concepts. The present research which is written in descriptive method aims to study "flower" and "bird" and the mystical literature related to these concepts. -

A Poet Builds a Nation.Pdf

DOI: 10.9744/kata.16.2.109-118 ISSN 1411-2639 (Print), ISSN 2302-6294 (Online) OPEN ACCESS http://kata.petra.ac.id A Poet Builds a Nation: Hafez as a Catalyst in Emerson’s Process of Developing American Literature Behnam Mirzababazadeh Fomeshi*, Adineh Khojastehpour Independent scholars * Corresponding author emails: [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT Numerous studies have tried to elucidate the relationship between Emerson and Hafez. While most of these studies laid emphasis on influence of Hafez on Emerson and others on similarity and/or infatuation, they left untouched some vital historical aspects of this relationship. Taking into consideration the political and literary discourses of Emerson‘s America may illuminate the issue. America‘s attempt to gain independence from Britain, Emerson‘s resolution to establish an American literary tradition, his break with the European fathers to establish that identity, his open-mindedness in receiving non-European cultures and the correspondence between Emerson‘s transcendentalism and Hafez‘s mysticism led to Hafez‘s reception by Emerson. Keywords: Hafez; Emerson; comparative literature; reception; national identity INTRODUCTION The relationship between Hafez and Emerson has been extensively studied. Most of the researchers In addition to being considered the father of trans- have highlighted influence and some have empha- cendentalism, the American poet and philosopher, sized similarity or infatuation. For instance, Fotouhi Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) was a remar- and Taebi (2012) believed that Emerson‘s poetic taste kable figure concerning Persian literature. The poet‘s made him study Persian poets and ―correspondence most fruitful years coincided with his careful study of between their mystical insight and his transcendental Persian poets.