The Anjuman-I Taraqqi-Yi Urdu, 1903-1971 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hindi and Urdu*

saadat hasan manto Hindi and Urdu* The hindi-urdu dispute has been raging for some time now. Maulvi Abdul Haq Sahib, Dr. Tara Singh, and Mahatma Gandhi know what there is to know about this dispute. For me, though, it has so far remained incomprehensible. Try as hard as I might, I just havenít been able to understand. Why are Hindus wasting their time supporting Hindi, and why are Muslims so beside themselves over the preservation of Urdu? A language is not made, it makes itself. And no amount of human effort can ever kill a language. When I tried to write something about this current hot issue, I ended up with the following conversation: munshi narain parshad: Iqbal Sahib, are you going to drink this soda water? mirza muhammad iqbal: Yes, I am. munshi: Why donít you drink lemon? iqbal: No particular reason. I just like soda water. At our house, everyone likes to drink it. munshi: In other words, you hate lemon. iqbal: Oh, not at all. Why would I hate it, Munshi Narain Parshad? Since everyone at home drinks soda water, Iíve sort of grown accustomed to it. Thatís all. But if you ask me, actually lemon tastes better than plain soda. munshi: Thatís precisely why I was surprised that you would prefer something salty over something sweet. And lemon isnít just sweet, it has a nice flavor. What do you think? * ìHindī aur Urdū,î ManÅo-Numā (Lahore: Sañg-e Mīl Publications, 1991), 560– 63. 205 206 • The Annual of Urdu Studies, No. 25 iqbal: Youíre absolutely right. -

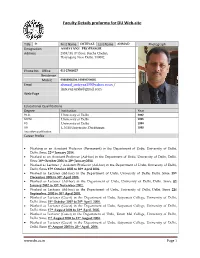

Faculty Details Proforma for DU Web-Site

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site Title Dr. First Name IMTEYAZ Last Name AHMAD Photograph Designation ASSISTANT PROFESSOR Address 2839/40, 4th floor, Kucha Chelan, Daryaganj, New Delhi. 110002. Phone No Office 011-27666627 Residence Mobile 09868008294 / 09899754685 Email [email protected] / [email protected] Web-Page Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. University of Delhi 2002 M.Phil. University of Delhi 1996 PG University of Delhi 1994 UG L.N.M.University, Darbhanga 1990 Any other qualification Career Profile Working as an Assistant Professor (Permanent) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 22nd January 2014. Worked as an Assistant Professor (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 16th October 2006 to 20th January2014. Worked as Lecturer / Assistant Professor (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 17th October 2005 to 30th April 2006. Worked as Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 28th December 2004 to 30th April 2005. Worked as Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 8th January 2002 to 15th November 2002. Worked as Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 21st September. 2000 to 30th April 2001. Worked as Lecturer (Guest) in the Department of Urdu, Satyawati College, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 31st October 2007 to 20th April. 2008. Worked as Lecturer (Guest) in the Department of Urdu, Satyawati College, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 17th August 2004 to 23rd April. -

Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology

Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology Merit List Department of Arabic (Bachelors, Morning) 2020 Abdul Haq Campus S# Form No Name Father Percent 1 202764 RABIAA MUHAMMAD AMIN 91.18 2 202095 NOORULAIN MUHAMMAD RAFIQ 67.27 3 205559 NASIR HUSSAIN KHUDA YAR 61.69 4 206180 ATA UR REHMAN ZAKIR UR REHMAN 54.22 Note: This list is conditional (Subjected to approval of Prof. Dr. Muhammad Zahid Concern Department and Varification of Documents). (Director Admission) Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology Merit List Department of Education (B.Ed 2.5 Years) (Bachelors, Morning) 2020 Abdul Haq Campus S# Form No Name Father Percent 1 204745 BUSHRA SAMI MUHAMMAD SAMI 78.34 2 204747 RUBAB SAMI MUHAMMAD SAMI 78.21 3 206250 SYED HASSNAN SYED MUHAMMAD SHAH 69.70 4 207469 MUHAMMAD AFTAB SARWAR MUHAMMAD SARWAR MALIK 68.67 5 205695 ALTAF AHMED MUHAMMAD MUNSIF 66.68 6 206100 MUHAMMAD FAIZAN MUHAMMAD IMRAN 66.38 7 200210 RAFIA FAROOQ MUHAMMAD FAROOQ 65.13 8 203771 NIMRAH AFTAB AFTAB AHMED 62.42 9 206939 MARINA RIAZ AHMED 61.70 10 203927 NUSRAT JABEEN DEEN MUHAMMAD 61.50 11 207432 BISMA MUHAMMAD YOUSUF BALOCH 60.69 12 202584 SEHRISH MUHAMMAD RIAZ 60.10 13 206963 HAYAT KHATOON KORAI MAZHAR UL HAQUE 60.00 14 202094 HUMAIRA MUHAMMAD KHAN 57.20 15 206719 ABDUL SAMAD MUHAMMAD RIAZ 56.36 16 206127 NAZIA MUHAMMAD YOUNUS 56.25 Note: This list is conditional (Subjected to approval of Prof. Dr. Muhammad Zahid Concern Department and Varification of Documents). (Director Admission) Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology Merit List -

Hajji Din Mohammad Biography

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Hajji Din Mohammad Biography Hajji Din Mohammad, a former mujahedin fighter from the Khalis faction of Hezb-e Islami, became governor of the eastern province of Nangarhar after the assassination of his brother, Hajji Abdul Qadir, in July 2002. He is also the brother of slain commander Abdul Haq. He is currently serving as the provincial governor of Kabul Province. Hajji Din Mohammad’s great-grandfather, Wazir Arsala Khan, served as Foreign Minister of Afghanistan in 1869. One of Arsala Khan's descendents, Taj Mohammad Khan, was a general at the Battle of Maiwand where a British regiment was decimated by Afghan combatants. Another descendent, Abdul Jabbar Khan, was Afghanistan’s first ambassador to Russia. Hajji Din Mohammad’s father, Amanullah Khan Jabbarkhel, served as a district administer in various parts of the country. Two of his uncles, Mohammad Rafiq Khan Jabbarkhel and Hajji Zaman Khan Jabbarkhel, were members of the 7th session of the Afghan Parliament. Hajji Din Mohammad’s brothers Abdul Haq and Hajji Abdul Qadir were Mujahedin commanders who fought against the forces of the USSR during the Soviet Occupation of Afghanistan from 1980 through 1989. In 2001, Abdul Haq was captured and executed by the Taliban. Hajji Abdul Qadir served as a Governor of Nangarhar Province after the Soviet Occupation and was credited with maintaining peace in the province during the years of civil conflict that followed the Soviet withdrawal. Hajji Abdul Qadir served as a Vice President in the newly formed post-Taliban government of Hamid Karzai, but was assassinated by unknown assailants in 2002. -

Gulshan Zubair Under the Supervision of Dr. Parwez Nazir

ROLE OF MUHAMMADAN EDUCATIONAL CONFERENCE IN THE EDUCATIONAL AND CULTURAL UPLIFTMENT OF INDIAN MUSLIMS ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Submitted for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History by Gulshan Zubair Under the Supervision of Dr. Parwez Nazir Center of Advanced Study Department of History ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2015 ABSTARACT Since the beginning of the 19th century the East India Company had acquired some provinces and had laid down a well planned system of education which was unacceptable to the Muslims. For its being modern and progressive Dr. W.W. Hunter in his book ‘Indian Musalmans’ accepted that the newly introduced system of education opposed the conditions and patterns prevalent in the Muslim Community. It did not suit to the general Muslim masses and there was a hatred among its members. The Muslims did not cooperate with the British and kept them aloof from the Western Education. Muslim community also felt that the education of the Christian which was taught in the Government school would convert them to Christianity. This was also a period of transition from medievalism to modernism in the history of the Indian Muslims. Sir Syed was quick to realize the Muslims degeneration and initiated a movement for the intellectual and cultural regeneration of the Muslim society. The Aligarh Movement marked a beginning of the new era, the era of renaissance. It was not merely an educational movement but an all pervading movement covering the entire extent of social and cultural life. The All India Muslim Educational conference (AIMEC) is a mile stone in the journey of Aligarh Movement and the Indian Muslims towards their educational and cultural development. -

Choosing Sides and Guiding Policy United States’ and Pakistan’S Wars in Afghanistan

UNIVERSITY OF FLORDA Choosing Sides and Guiding Policy United States’ and Pakistan’s Wars in Afghanistan Azhar Merchant 4/24/2019 Table of Contents I. Introduction… 2 II. Political Settlement of the Mujahedeen War… 7 III. The Emergence of the Taliban and the Lack of U.S. Policy… 27 IV. The George W. Bush Administration… 50 V. Conclusion… 68 1 I. Introduction Forty years of war in Afghanistan has encouraged the most extensive periods of diplomatic and military cooperation between the United States and Pakistan. The communist overthrow of a relatively peaceful Afghan government and the subsequent Soviet invasion in 1979 prompted the United States and Pakistan to cooperate in funding and training Afghan mujahedeen in their struggle against the USSR. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Afghanistan entered a period of civil war throughout the 1990s that nurtured Islamic extremism, foreign intervention, and the rise of the Taliban and Al-Qaeda, ultimately culminating in the devastating attacks against Americans on September 11th. Seventeen years later, the United States continues its war in Afghanistan while its relationship with Pakistan has deteriorated to an all-time low. The mutual fear of Soviet expansionism was the unifying cause for Americans and Pakistanis to work together in the 1980s, yet as the wars in Afghanistan evolved, so did the countries’ respective aims and objectives.1 After the Soviets were successfully pushed out of the region by the mujahedeen, the United States felt it no longer had any reason to stay. The initial policy aim of destabilizing the USSR through prolonged covert conflict in Afghanistan was achieved. -

Individuality in the Educational Philosophy of Allama Muhammad Iqbal1

Individuality In the Educational Philosophy of Allama Muhammad Iqbal1 Imam Bahroni Faculty of Islamic Education Darussalam Institute of Islamic Studies Gontor Email: [email protected] Abstract Nowadays, Muslim Ummah all over the world likely at the cross road, at the position where they watch clearly a phenomenon of life that directs them into surprising modern civilization with full creativities and innovations, but far away from the true values of Islamic education. On the other hand, they observe vividly numerous dimensions of life that direct every individual into strong morality, norms and right way of life to discover the Ultimate Reality. This social fact at the end compelled every one of modern people to select which one among these two is the correct ideal for the truth of life. This article tries to elaborate the concept of individuality in the educational philosophy of Allama Muhammad Iqbal2 . In his Lectures, Iqbal elaborated that individuality is not a datum but an achievement. It is the fruit of a constant, strenuous effort in and against the forces of the external environment as well as the disruptive tendencies within man himself. The life of individuality (the Ego), he further explained is a kind of tension caused by the Ego invading the environment and the environment invading the Ego. An individual is the basis of all aspects of educations, which then must be educated and concerned together with the development of its relationship to the community. Like the philosopher, the educator must necessarily inquire into the nature of these two terms of his active individual and the environment, which ultimately determine the solution of all his problems. -

6455.Pdf, PDF, 1.27MB

Overall List Along With Domicile and Post Name Father Name District Post Shahab Khan Siraj Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sana Ullah Muhammad Younas Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Mahboob Ali Fazal Rahim Swat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tahir Saeed Saeed Ur Rehman Kohat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Owais Qarni Raham Dil Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Ashfaq Ahmad Zarif Khan Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Saud Khan Haji Minak Khan Khyber 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Qamar Jan Syed Marjan Kurram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Kamil Khan Wakeel Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Waheed Gul Muhammad Qasim Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tanveer Ahmad Mukhtiar Ahmad Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Faheem Muhammad Aslam PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muslima Bibi Jan Gul Dera Ismail Khan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Zahid Muhammad Saraf Batagram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Riaz Khan Muhammad Anwar Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Bakht Taj Abdul Khaliq Shangla 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Hidayat Ullah Fazal Ullah Swabi 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Wajid Ali Malang Jan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sahar Rashed Abdur Rasheed Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Afsar Khan Afridi Ghulam Nabi PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Khan Manazir Khan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Liaqat Ali Malik Aman Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Iqbal Parvaiz Khan Mardan 01. -

Afghanistan INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:01/02/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Afghanistan INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: ABBASIN 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: --/--/1969. POB: Sheykhan village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan a.k.a: MAHSUD, Abdul Aziz Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):AFG0121 (UN Ref): TAi.155 (Further Identifiying Information):Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we- work/Notices/View-UN-Notices-Individuals click here. Listed on: 21/10/2011 Last Updated: 01/02/2021 Group ID: 12156. 2. Name 6: ABDUL AHAD 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. Title: Mr DOB: --/--/1972. POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Nationality: Afghan National Identification no: 44323 (Afghan) (tazkira) Position: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):AFG0094 (UN Ref): TAi.121 (Further Identifiying Information): Belongs to Hotak tribe. Review pursuant to Security Council resolution 1822 (2008) was concluded on 29 Jul. 2010. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/ Notices/View-UN-Notices-Individuals click here. Listed on: 23/02/2001 Last Updated: 01/02/2021 Group ID: 7055. -

Religious, Social and Political Trends in Tahzib-Ul-Akhlaq of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan

RELIGIOUS, SOCIAL AND POLITICAL TRENDS IN TAHZIB-UL-AKHLAQ OF SIR SYED AHMAD KHAN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement* for the Award of the Degree of iWaiter of $fjtlo£opl)p IN HISTORY BY PERWfcZ NAZIR Under the supervision of DR. M. P. SINGH CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALFGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALK3ARH (INDIA) 1995 men /• £>£ - 21SO *<&j*i. ^.!-> 2 4 AUG 1934 CI*^ CKLID-20CZ CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY _ , . i External : 4 0 0 1 41> Telephones J Interna) J4, DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH—202 002 (U.P.). INDIA L^ertLticah This is to certify that the dissertation 'Religious, Social and Political Trends in Tahzib-ul-Akhlaq of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan' submitted by Mr. Perwez Nazir is an original piece of research prepared under my supervision. It is based on original sources and first hand information and is fit for the award of M. Phil, degree. (M.P. Singh) Supervisor 3o'*.ir oDedlca ted Do trainer cine er CONTENTS Page Nc PREFACE I . TAHZIB - UL -AKHLAQ 1-14 II. SIR SYED AHMAD KHAN 15-32 III. RELIGICUS TRENDS IN TAHZIB- UL-AKHLAQ 3 3 - 5 G IV. SOCIAL TRENDS IN TAHZIB-UL-AKHLAQ 51-68 V. POLITICAL TRENDS IN TAHZIB-UL-AKHLAQ 69-86 VI. SIR SYED AHMAD KHAN AND NATIONAL MOVEMENT 87-94 BIBLIOGRAPHY 95-103 PREFACE For educating the masses newspapers, magazines and other Press media had been playing a very significant role. Sir Syed Ahmad Khar, during and after the revolt of 1857 found the Muslim illiterate, ignorant, backward, economically in hardship and distress. -

Urdu Nationalism and Colonial India

W&M ScholarWorks Arts & Sciences Articles Arts and Sciences 2014 The Language of Secular Islam: Urdu Nationalism and Colonial India Chitralekha Zutshi College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/aspubs Recommended Citation Zutshi, C. (2014). Kavita Saraswathi Datla. The Language of Secular Islam: Urdu Nationalism and Colonial India. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts and Sciences at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Articles by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Asia 163 In addition to presenting an analytics of enclave, versations regarding India’s secular national culture Bhattacharya’s work also extends our understanding of and the position of Indian Muslims within it. Datla puts the plantation within colonial and tropical medicine. forward a noteworthy definition of secularism for this Over the course of the early twentieth century, the plan- moment in colonial India, arguing that it was not so tation enclave emerged worldwide as one of the sites for much “an approach to politics or a solution to com- the circulation and diffusion of scientific and medical munal problems and rather more a set of projects” (p. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ahr/article-abstract/119/1/163/20306 by College of William and Mary user on 18 December 2018 knowledge. As we have learned from the now signifi- 9), all of which attempted to rethink traditional ideas, cant literature on tropical medicine (largely produced language, and culture to relocate them within a national in relation to its careers in colonial Africa), tropical vision of India in the future. -

PAN-ISLAMISM and the NORTH WEST FRONTIER PROVINCE of BRITISH INDIA (1897-1918) Dr. Abdul RAUF* Abstract the North West Frontier

Abdul Rauf PAN-ISLAMISM AND THE NORTH WEST FRONTIER PROVINCE OF BRITISH INDIA (1897-1918) Dr. Abdul RAUF* Abstract The North West Frontier Province NWFP, being a strategic region of the Indo-Pak Subcontinent, played a very important role in the political upheavals in British India. Religion played a pivotal role in shaping events which took place in the region. The Pan-Islamic slogans raised in India, not only attracted the Muslims of the NWFP but it augmented their armed struggle against the British in a more forceful vigour. Consequently, they faced a more severe treatment from the British including several military expeditions against them. The role of Pan Islamic feelings in the resistance movements, launched in the province, has not been dealt properly by the researchers. In the following pages, an effort has been made to assess the role of these feelings in the on going armed struggle of the Pukhtuns; particularly in tribal areas (North West of India) against the British and also to bring out details of some of the personalities of the province who went to Turkey and contributed physically to the cause of Pan-Islamism. Introduction Pan-Islamism1 refers to the movement which aims to unite the diversified Muslims on the basis of their common religion. There are several instances in the Holy Qur‘an and the traditions of the Holy prophet Mohammad (PBUH), which emphasises the concept of Muslim brotherhood and good feelings for the fellow Muslims. However, the political unity of the Muslims under one caliph lasted till the fall of the Umayyads and the establishment of Abbaside rule in 132 A.H.