Whatever Happened to Hindustani?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Hindi and Urdu*

saadat hasan manto Hindi and Urdu* The hindi-urdu dispute has been raging for some time now. Maulvi Abdul Haq Sahib, Dr. Tara Singh, and Mahatma Gandhi know what there is to know about this dispute. For me, though, it has so far remained incomprehensible. Try as hard as I might, I just havenít been able to understand. Why are Hindus wasting their time supporting Hindi, and why are Muslims so beside themselves over the preservation of Urdu? A language is not made, it makes itself. And no amount of human effort can ever kill a language. When I tried to write something about this current hot issue, I ended up with the following conversation: munshi narain parshad: Iqbal Sahib, are you going to drink this soda water? mirza muhammad iqbal: Yes, I am. munshi: Why donít you drink lemon? iqbal: No particular reason. I just like soda water. At our house, everyone likes to drink it. munshi: In other words, you hate lemon. iqbal: Oh, not at all. Why would I hate it, Munshi Narain Parshad? Since everyone at home drinks soda water, Iíve sort of grown accustomed to it. Thatís all. But if you ask me, actually lemon tastes better than plain soda. munshi: Thatís precisely why I was surprised that you would prefer something salty over something sweet. And lemon isnít just sweet, it has a nice flavor. What do you think? * ìHindī aur Urdū,î ManÅo-Numā (Lahore: Sañg-e Mīl Publications, 1991), 560– 63. 205 206 • The Annual of Urdu Studies, No. 25 iqbal: Youíre absolutely right. -

Reassessing Religion and Politics in the Life of Jagjivan Ram¯

religions Article Reassessing Religion and Politics in the Life of Jagjivan Ram¯ Peter Friedlander South and South East Asian Studies Program, School of Culture History and Language, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2600, Australia; [email protected] Received: 13 March 2020; Accepted: 23 April 2020; Published: 1 May 2020 Abstract: Jagjivan Ram (1908–1986) was, for more than four decades, the leading figure from India’s Dalit communities in the Indian National Congress party. In this paper, I argue that the relationship between religion and politics in Jagjivan Ram’s career needs to be reassessed. This is because the common perception of him as a secular politician has overlooked the role that his religious beliefs played in forming his political views. Instead, I argue that his faith in a Dalit Hindu poet-saint called Ravidas¯ was fundamental to his political career. Acknowledging the role that religion played in Jagjivan Ram’s life also allows us to situate discussions of his life in the context of contemporary debates about religion and politics. Jeffrey Haynes has suggested that these often now focus on whether religion is a cause of conflict or a path to the peaceful resolution of conflict. In this paper, I examine Jagjivan Ram’s political life and his belief in the Ravidas¯ ¯ı religious tradition. Through this, I argue that Jagjivan Ram’s career shows how political and religious beliefs led to him favoring a non-confrontational approach to conflict resolution in order to promote Dalit rights. Keywords: religion; politics; India; Congress Party; Jagjivan Ram; Ravidas;¯ Ambedkar; Dalit studies; untouchable; temple building 1. -

Sl. No. INSTITUTE NAME & ADDRESS STATE 1 ALAGAPPA

ANNEXURE - I Sl. INSTITUTE NAME & ADDRESS STATE No. 1 ALAGAPPA CHETTIAR COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY, KARAIKUDI, SIVAGANGAI DISTRICT-630004, TAMILNADU. TAMILNADU 2 ASSAM ENGINEERING INSTITUTE, MRD ROAD, CHANDMARI, KAMRUP, GUWAHATI- 781003, ASSAM ASSAM 3 BEANT COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY, GURDASPUR, POST BOX NO. 13, VILLAGE BARIAR, GURDASPUR-143521, PUNJAB PUNJAB 4 BUNDELKHAND INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY, JHANSI, KANPUR ROAD-284128, UTTAR PRADESH UTTAR PRADESH 5 CH. DEVI LAL MEMORIAL GOVT. ENGG. COLLEGE, 21 MILESTONE, SIRSA DABWALI ROAD, PANNIWALA MOTA, SIRSA-125077, HARYANA HARYANA 6 COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY, BHUBANESWAR, GHATIKIA, KHORDHA, BHUBANESWAR-751003, ORISSA ODISHA 7 COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, TRIVANDRUM,THIRUVANANTHAPURAM-695016, KERALA. KERALA 8 G.B. PANT UNIVERSITY OF AGRICULTURE & TECHNOLOGY COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY, PANTNAGAR, UDHAM SINGH NAGAR, PANTNAGAR-263145, UTTARAKHAND UTTARAKHAND 9 DR. AMBEDKAR INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY,OUTER RING ROAD, NEAR JNANA, BHARATHI CAMPUR, MALLATHALLI, BANGALORE-560056, KARNATAKA. KARNATAKA 10 DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY LONERE, VIDHYAVISHAR, AP LONERE, TAL MANGAON DIST, RAIGAD, MAHARASHTRA - 402103 MAHARASHTRA 11 THE MAHARAJA SAYAJIRAO UNIVERSITY OF BARODA, VADODRA -390001, GUJARAT GUJARAT 12 GOA COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, FARMAGUDI PONDA-403401,GOA GOA 13 GOVERNEMENT ENGINEERING COLLEGE KUSHALANGAR MANDAPATNA, BM ROAD, KUSHALNAGAR-571234, KARNATAKA KARNATAKA 14 GOVERNMENT ENGINEERING COLLEGE IDUKKI, PAINAVU P.O. IDUKKI DISTRICT-685603, KERALA KERALA 15 GOVERNMENT COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, BANGALORE HIGHWAYS SALEM-11, SALEM-636011, TAMILNADU. TAMILNADU 16 GOVERNMENT COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, BARGUR, MADEPALLI POST BARGUR, KRISHNAGIRI-635104, TAMILNADU TAMILNADU 17 GOVERNMENT COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, TIRUNELVELI, PALAYAMKOTTAI, TIRUNELVELI -627007, TAMILNADU TAMILNADU 18 GOVERNMENT COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AMRAVATI, NEAR KATHORA NAKA, V.M.V. POST OFFICE, AMRAVATI -444604, MAHARASHTRA MAHARASHTRA 19 GOVERNMENT COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY, THADAGAM ROAD, COIMBATORE-641013, TAMILNADU. -

1: Scope and Important of Urdu: Urdu Is a Standardized Register of the Hindustani Language It Is the National Language and Ling

1: Scope And Important Of Urdu: Urdu Is A Standardized Register Of The Hindustani Language It Is The National Language And Lingua Franca Of Pakistan, And An Official Language Of Six States Of India. It Is Also One Of The 22 Official Languages Recognized In The Constitution Of India. Urdu Is Historically Associated With The Muslims Of The Northern Indian Subcontinent. Apart From Specialized Vocabulary, Urdu Is Mutually Intelligible With Standard Hindi, Another Recognized Register Of Hindustani. The Urdu Variant Received Recognition And Patronage Under British Rule When The British Replaced The Persian And Local Official Languages With The Urdu And English Languages In The North Indian Regions Of Jammu and Kashmir In 1846 And Punjab In 1849. Urdu, Like Hindi, Is A Form Of Hindustani. It Evolved From The Medieval (6th To 13th Century) Apabhraṃśa Register Of The Preceding Shauraseni Language, A Middle Indo-Aryan Language That Is Also The Ancestor Of Other Modern Languages, Including The Punjabi Dialects. Urdu Developed Under The Influence Of The Persian And Arabic Languages, Both Of Which Have Contributed A Significant Amount Of Vocabulary To Formal Speech around 99% Of Urdu Verbs Have Their Roots In Sanskrit And Prakrit. Although The Word Urdu Itself Is Derived From The Turkic Word Ordu Or Orda, From Which English Horde Is Also Derived, Turkic Borrowings In Urdu Are Minimal And Urdu Is Not Genetically Related To The Turkic Languages. Urdu Words Originating From Chagatai And Arabic Were Borrowed Through Persian And Hence Are Personalized Versions Of The Original Words. For Instance, The Arabic Ta' Marbuta Changes To He Or Te . -

Linguistics Development Team

Development Team Principal Investigator: Prof. Pramod Pandey Centre for Linguistics / SLL&CS Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Email: [email protected] Paper Coordinator: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Department of Linguistics, Deccan College Post-Graduate Research Institute, Pune- 411006, [email protected] Content Writer: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Prof H. S. Ananthanarayana Content Reviewer: Retd Prof, Department of Linguistics Osmania University, Hyderabad 500007 Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family Description of Module Subject Name Linguistics Paper Name Historical and Comparative Linguistics Module Title Indo-Aryan Language Family Module ID Lings_P7_M1 Quadrant 1 E-Text Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family INDO-ARYAN LANGUAGE FAMILY The Indo-Aryan migration theory proposes that the Indo-Aryans migrated from the Central Asian steppes into South Asia during the early part of the 2nd millennium BCE, bringing with them the Indo-Aryan languages. Migration by an Indo-European people was first hypothesized in the late 18th century, following the discovery of the Indo-European language family, when similarities between Western and Indian languages had been noted. Given these similarities, a single source or origin was proposed, which was diffused by migrations from some original homeland. This linguistic argument is supported by archaeological and anthropological research. Genetic research reveals that those migrations form part of a complex genetical puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population. Literary research reveals similarities between various, geographically distinct, Indo-Aryan historical cultures. The Indo-Aryan migrations started in approximately 1800 BCE, after the invention of the war chariot, and also brought Indo-Aryan languages into the Levant and possibly Inner Asia. -

Bejeweled with Bengal

2 Indian Design Cover Story Bejeweled With Bengal Tanishq unveils yet another reimagined concept in its flagship store in Kolkata which, celebrates the rich heritage of handicrafts of the region by infusing exquisite real art installations that narrate traditional wedding stories through illustrations, materials and forms. anishq re-launched its flagship this new design, the Space Design and walls which would have otherwise been at Camac Street, Kolkata in a new Visual Experience Studio at Tanishq had clad with visuals were instead treated as a reimagined form with the objective of been working on concepts and exploring colonnade of carefully proportioned panels T and arches extending across two sides, amplifying its positioning as a differentiated the avenues of creatively integrating craft design centric brand. The 8000 sq. ft. heritage into the retail store space. The creating the grand ambience reminiscent of showroom is inspired by the heritage of overarching intent of this venture was to Kolkata's bungalows." Adding authenticity Bengal and is an ode to its rich art forms. communicate wedding stories in the store to the setting, the balustrades of the gently Sharing the thought behind this new store using the unexplored arts and crafts. "The curving marble stairways as well as the concept, Chitti Babu Govindarajan, Head new store at Camac Street proved to be a cast metal spiral staircase were sourced - Visual Design at Tanishq says, "Ever since good opportunity for us to try this design from Bow Bazaar, the metal works hub of its launch, the retail identity of Tanishq has intent. West Bengal has rich heritage of living Kolkata. -

The Status of the Least Documented Language Families in the World

Vol. 4 (2010), pp. 177-212 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4478 The status of the least documented language families in the world Harald Hammarström Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig This paper aims to list all known language families that are not yet extinct and all of whose member languages are very poorly documented, i.e., less than a sketch grammar’s worth of data has been collected. It explains what constitutes a valid family, what amount and kinds of documentary data are sufficient, when a language is considered extinct, and more. It is hoped that the survey will be useful in setting priorities for documenta- tion fieldwork, in particular for those documentation efforts whose underlying goal is to understand linguistic diversity. 1. InTroducTIon. There are several legitimate reasons for pursuing language documen- tation (cf. Krauss 2007 for a fuller discussion).1 Perhaps the most important reason is for the benefit of the speaker community itself (see Voort 2007 for some clear examples). Another reason is that it contributes to linguistic theory: if we understand the limits and distribution of diversity of the world’s languages, we can formulate and provide evidence for statements about the nature of language (Brenzinger 2007; Hyman 2003; Evans 2009; Harrison 2007). From the latter perspective, it is especially interesting to document lan- guages that are the most divergent from ones that are well-documented—in other words, those that belong to unrelated families. I have conducted a survey of the documentation of the language families of the world, and in this paper, I will list the least-documented ones. -

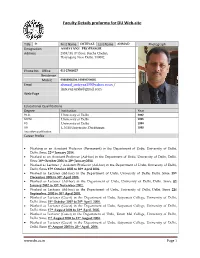

Faculty Details Proforma for DU Web-Site

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site Title Dr. First Name IMTEYAZ Last Name AHMAD Photograph Designation ASSISTANT PROFESSOR Address 2839/40, 4th floor, Kucha Chelan, Daryaganj, New Delhi. 110002. Phone No Office 011-27666627 Residence Mobile 09868008294 / 09899754685 Email [email protected] / [email protected] Web-Page Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. University of Delhi 2002 M.Phil. University of Delhi 1996 PG University of Delhi 1994 UG L.N.M.University, Darbhanga 1990 Any other qualification Career Profile Working as an Assistant Professor (Permanent) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 22nd January 2014. Worked as an Assistant Professor (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 16th October 2006 to 20th January2014. Worked as Lecturer / Assistant Professor (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 17th October 2005 to 30th April 2006. Worked as Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 28th December 2004 to 30th April 2005. Worked as Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 8th January 2002 to 15th November 2002. Worked as Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 21st September. 2000 to 30th April 2001. Worked as Lecturer (Guest) in the Department of Urdu, Satyawati College, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 31st October 2007 to 20th April. 2008. Worked as Lecturer (Guest) in the Department of Urdu, Satyawati College, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 17th August 2004 to 23rd April. -

TURBANS and TOP HATS Indian Interpreters in the Colony of Natal

TURBANS AND TOP HATS Indian Interpreters in the Colony of Natal, 1880-1910 by PRINISHA BADASSY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Social Science – Honours in the Department of Historical Studies, Faculty of Human Science, University of Natal 2002 University of Natal Abstract TURBANS AND TOP HATS Indian Interpreters in the Colony of Natal, 1880-1910 by PRINISHA BADASSY Supervised by: Professor Jeff Guy Department of Historical Studies This dissertation is concerned with an historical examination of Indian Interpreters in the British Colony of Natal during the period, 1880 to 1910. These civil servants were intermediaries between the Colonial State and the wider Indian population, who apart from the ‘Indentureds’, included storekeepers, traders, politicians, railway workers, constables, court messengers, teachers and domestic servants. As members of an Indian elite and the Natal Civil Service, they were pioneering figures in overcoming the shackles of Indenture but at the same time they were active agents in the perpetuation of colonial oppression, and hegemonic imperialist ideas. Theirs was an ambiguous and liminal position, existing between worlds, as Occidentals and Orientals. Contents Acknowledgements iii List of Images iv List of Tables v List of Abbreviations vi Introduction 8 Chapter One – Indenture, Interpreters and Empire 13 Chapter Two – David Vinden 30 Chapter Three – Cows and Heifers 51 Chapter Four – A Diabolical Conspiracy 74 Conclusion 94 Appendix 98 Bibliography 124 Acknowledgments Out of a sea-bed of my search years I have put together again a million fragments of my brother’s ancient mirror… and as I look deep into it I see a million shades of fractured brown, merging into an unstoppable tide… David Campbell The history of Indians in Natal is one that is incomplete and developing. -

Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe Romanization: KNAB 2012

Institute of the Estonian Language KNAB: Place Names Database 2012-10-11 Tai Lü / ᦺᦑᦟᦹᧉ Tai Lùe romanization: KNAB 2012 I. Consonant characters 1 ᦀ ’a 13 ᦌ sa 25 ᦘ pha 37 ᦤ da A 2 ᦁ a 14 ᦍ ya 26 ᦙ ma 38 ᦥ ba A 3 ᦂ k’a 15 ᦎ t’a 27 ᦚ f’a 39 ᦦ kw’a 4 ᦃ kh’a 16 ᦏ th’a 28 ᦛ v’a 40 ᦧ khw’a 5 ᦄ ng’a 17 ᦐ n’a 29 ᦜ l’a 41 ᦨ kwa 6 ᦅ ka 18 ᦑ ta 30 ᦝ fa 42 ᦩ khwa A 7 ᦆ kha 19 ᦒ tha 31 ᦞ va 43 ᦪ sw’a A A 8 ᦇ nga 20 ᦓ na 32 ᦟ la 44 ᦫ swa 9 ᦈ ts’a 21 ᦔ p’a 33 ᦠ h’a 45 ᧞ lae A 10 ᦉ s’a 22 ᦕ ph’a 34 ᦡ d’a 46 ᧟ laew A 11 ᦊ y’a 23 ᦖ m’a 35 ᦢ b’a 12 ᦋ tsa 24 ᦗ pa 36 ᦣ ha A Syllable-final forms of these characters: ᧅ -k, ᧂ -ng, ᧃ -n, ᧄ -m, ᧁ -u, ᧆ -d, ᧇ -b. See also Note D to Table II. II. Vowel characters (ᦀ stands for any consonant character) C 1 ᦀ a 6 ᦀᦴ u 11 ᦀᦹ ue 16 ᦀᦽ oi A 2 ᦰ ( ) 7 ᦵᦀ e 12 ᦵᦀᦲ oe 17 ᦀᦾ awy 3 ᦀᦱ aa 8 ᦶᦀ ae 13 ᦺᦀ ai 18 ᦀᦿ uei 4 ᦀᦲ i 9 ᦷᦀ o 14 ᦀᦻ aai 19 ᦀᧀ oei B D 5 ᦀᦳ ŭ,u 10 ᦀᦸ aw 15 ᦀᦼ ui A Indicates vowel shortness in the following cases: ᦀᦲᦰ ĭ [i], ᦵᦀᦰ ĕ [e], ᦶᦀᦰ ăe [ ∎ ], ᦷᦀᦰ ŏ [o], ᦀᦸᦰ ăw [ ], ᦀᦹᦰ ŭe [ ɯ ], ᦵᦀᦲᦰ ŏe [ ]. -

KHA in ANCIENT INDIAN MATHEMATICS It Was in Ancient

KHA IN ANCIENT INDIAN MATHEMATICS AMARTYA KUMAR DUTTA It was in ancient India that zero received its first clear acceptance as an integer in its own right. In 628 CE, Brahmagupta describes in detail rules of operations with integers | positive, negative and zero | and thus, in effect, imparts a ring structure on integers with zero as the additive identity. The various Sanskrit names for zero include kha, ´s¯unya, p¯urn. a. There was an awareness about the perils of zero and yet ancient Indian mathematicians not only embraced zero as an integer but allowed it to participate in all four arithmetic operations, including as a divisor in a division. But division by zero is strictly forbidden in the present edifice of mathematics. Consequently, verses from ancient stalwarts like Brahmagupta and Bh¯askar¯ac¯arya referring to numbers with \zero in the denominator" shock the modern reader. Certain examples in the B¯ıjagan. ita (1150 CE) of Bh¯askar¯ac¯arya appear as absurd nonsense. But then there was a time when square roots of negative numbers were considered non- existent and forbidden; even the validity of subtracting a bigger number from a smaller number (i.e., the existence of negative numbers) took a long time to gain universal acceptance. Is it not possible that we too have confined ourselves to a certain safe convention regarding the zero and that there could be other approaches where the ideas of Brahmagupta and Bh¯askar¯ac¯arya, and even the examples of Bh¯askar¯ac¯arya, will appear not only valid but even natural? Enterprising modern mathematicians have created elaborate legal (or technical) machinery to overcome the limitations imposed by the prohibition against use of zero in the denominator.