Finding a Home for Urdu: Islam and Science in Modern South Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hindi and Urdu*

saadat hasan manto Hindi and Urdu* The hindi-urdu dispute has been raging for some time now. Maulvi Abdul Haq Sahib, Dr. Tara Singh, and Mahatma Gandhi know what there is to know about this dispute. For me, though, it has so far remained incomprehensible. Try as hard as I might, I just havenít been able to understand. Why are Hindus wasting their time supporting Hindi, and why are Muslims so beside themselves over the preservation of Urdu? A language is not made, it makes itself. And no amount of human effort can ever kill a language. When I tried to write something about this current hot issue, I ended up with the following conversation: munshi narain parshad: Iqbal Sahib, are you going to drink this soda water? mirza muhammad iqbal: Yes, I am. munshi: Why donít you drink lemon? iqbal: No particular reason. I just like soda water. At our house, everyone likes to drink it. munshi: In other words, you hate lemon. iqbal: Oh, not at all. Why would I hate it, Munshi Narain Parshad? Since everyone at home drinks soda water, Iíve sort of grown accustomed to it. Thatís all. But if you ask me, actually lemon tastes better than plain soda. munshi: Thatís precisely why I was surprised that you would prefer something salty over something sweet. And lemon isnít just sweet, it has a nice flavor. What do you think? * ìHindī aur Urdū,î ManÅo-Numā (Lahore: Sañg-e Mīl Publications, 1991), 560– 63. 205 206 • The Annual of Urdu Studies, No. 25 iqbal: Youíre absolutely right. -

Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism

Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review 51 | 2016 Global History, East Africa and The Classical Traditions Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism Phiroze Vasunia Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/314 Publisher IFRA - Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique Printed version Date of publication: 1 March 2016 Number of pages: 21-43 ISSN: 2071-7245 Electronic reference Phiroze Vasunia, « Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism », Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review [Online], 51 | 2016, Online since 07 May 2019, connection on 08 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/314 Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review Global History, East Africa and the Classical Traditions. Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism Phiroze Vasunia Can the Ethiopian change his skinne? or the leopard his spots? Jeremiah 13.23, in the King James Version (1611) May a man of Inde chaunge his skinne, and the cat of the mountayne her spottes? Jeremiah 13.23, in the Bishops’ Bible (1568) I once encountered in Sicily an interesting parallel to the ancient confusion between Indians and Ethiopians, between east and south. A colleague and I had spent some pleasant moments with the local custodian of an archaeological site. Finally the Sicilian’s curiosity prompted him to inquire of me “Are you Chinese?” Frank M. Snowden, Blacks in Antiquity (1970) The ancient confusion between Ethiopia and India persists into the late European Enlightenment. Instances of the confusion can be found in the writings of distinguished Orientalists such as William Jones and also of a number of other Europeans now less well known and less highly regarded. -

YES BANK LTD.Pdf

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE ANDAMAN Ground floor & First Arpan AND floor, Survey No Basak - NICOBAR 104/1/2, Junglighat, 098301299 ISLAND ANDAMAN Port Blair Port Blair - 744103. PORT BLAIR YESB0000448 04 Ground Floor, 13-3- Ravindra 92/A1 Tilak Road Maley- ANDHRA Tirupati, Andhra 918374297 PRADESH CHITTOOR TIRUPATI, AP Pradesh 517501 TIRUPATI YESB0000485 779 Ground Floor, Satya Akarsha, T. S. No. 2/5, Door no. 5-87-32, Lakshmipuram Main Road, Guntur, Andhra ANDHRA Pradesh. PIN – 996691199 PRADESH GUNTUR Guntur 522007 GUNTUR YESB0000587 9 Ravindra 1ST FLOOR, 5 4 736, Kumar NAMPALLY STATION Makey- ANDHRA ROAD,ABIDS, HYDERABA 837429777 PRADESH HYDERABAD ABIDS HYDERABAD, D YESB0000424 9 MR. PLOT NO.18 SRI SHANKER KRUPA MARKET CHANDRA AGRASEN COOP MALAKPET REDDY - ANDHRA URBAN BANK HYDERABAD - HYDERABA 64596229/2 PRADESH HYDERABAD MALAKPET 500036 D YESB0ACUB02 4550347 21-1-761,PATEL MRS. AGRASEN COOP MARKET RENU ANDHRA URBAN BANK HYDERABAD - HYDERABA KEDIA - PRADESH HYDERABAD RIKABGUNJ 500002 D YESB0ACUB03 24563981 2-4-78/1/A GROUND FLOOR ARORA MR. AGRASEN COOP TOWERS M G ROAD GOPAL ANDHRA URBAN BANK SECUNDERABAD - HYDERABA BIRLA - PRADESH HYDERABAD SECUNDRABAD 500003 D YESB0ACUB04 64547070 MR. 15-2-391/392/1 ANAND AGRASEN COOP SIDDIAMBER AGARWAL - ANDHRA URBAN BANK BAZAR,HYDERABAD - HYDERABA 24736229/2 PRADESH HYDERABAD SIDDIAMBER 500012 D YESB0ACUB01 4650290 AP RAJA MAHESHWARI 7 1 70 DHARAM ANDHRA BANK KARAN ROAD HYDERABA 40 PRADESH HYDERABAD AMEERPET AMEERPET 500016 D YESB0APRAJ1 23742944 500144259 LADIES WELFARE AP RAJA CENTRE,BHEL ANDHRA MAHESHWARI TOWNSHIP,RC HYDERABA 40 PRADESH HYDERABAD BANK BHEL PURAM 502032 D YESB0APRAJ2 23026980 SHOP NO:G-1, DEV DHANUKA PRESTIGE, ROAD NO 12, BANJARA HILLS HYDERABAD ANDHRA ANDHRA PRADESH HYDERABA PRADESH HYDERABAD BANJARA HILLS 500034 D YESB0000250 H NO. -

Copyright by Gwendolyn Sarah Kirk 2016

Copyright by Gwendolyn Sarah Kirk 2016 The Dissertation committee for Gwendolyn Sarah Kirk certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Uncivilized language and aesthetic exclusion: Language, power and film production in Pakistan Committee: _____________________________ Craig Campbell, Co-Supervisor _____________________________ Elizabeth Keating, Co-Supervisor _____________________________ Kamran Ali _____________________________ Patience Epps _____________________________ Ali Khan _____________________________ Kathleen Stewart _____________________________ Anthony Webster Uncivilized language and aesthetic exclusion: Language, power and film production in Pakistan by Gwendolyn Sarah Kirk, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2016 To my parents Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible first and foremost without the kindness and generosity of the filmmakers I worked with at Evernew Studio. Parvez Rana, Hassan Askari, Z.A. Zulfi, Pappu Samrat, Syed Noor, Babar Butt, and literally everyone else I met in the film industry were welcoming and hospitable beyond what I ever could have hoped or imagined. The cast and crew of Sharabi, in particular, went above and beyond to facilitate my research and make sure I was at all times comfortable and safe and had answers to whatever stupid questions I was asking that day! Along with their kindness, I was privileged to witness their industry, creativity, and perseverance, and I will be eternally inspired by and grateful to them. My committee might seem large at seven members, but all of them have been incredibly helpful and supportive throughout my time in graduate school, and each of them have helped develop different dimensions of this work. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Bangladesh Assessment

BANGLADESH ASSESSMENT October 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit 1 CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 – 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY General 2.1 – 2.3 Languages 2.4 Economy 2.5 – 2.6 III HISTORY Pre-independence: 1947 – 1971 3.1 – 3.4 1972-1982 3.5 – 3.8 1983 – 1990 3.9 – 3.15 1991 – 1996 3.16 – 3.21 1997 - 1999 3.22 – 3.32 January 2000 - December 2000 3.33 – 3.35 January 2001 – October 2001 3.36 – 3.39 IV INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE 4.1 POLITICAL SYSTEM Constitution 4.1.1 – 4.1.3 Government 4.1.4 – 4.1.5 President 4.1.6 – 4.1.7 Parliament 4.1.8 – 4.1.10 4.2 JUDICIAL SYSTEM 4.2.1 – 4.2.4 4.3 SECURITY General 4.3.1 – 4.3.4 1974 Special Powers Act 4.3.5 – 4.3.7 Public Safety Act 4.3.8 2 V HUMAN RIGHTS 5.1 INTRODUCTION 5.1.1 – 5.1.3 5.2 GENERAL ASSESSMENT Torture 5.2.1 – 5.2.3 Police 5.2.4 – 5.2.9 Supervision of Elections 5.2.10 – 5.2.12 Human Rights Groups 5.2.13 – 5.2.14 5.3 SPECIFIC GROUPS Religious Minorities 5.3.1 – 5.3.6 Biharis 5.3.7 – 5.3.14 Chakmas 5.3.15 – 5.3.16 Rohingyas 5.3.17 – 5.3.18 Ahmadis 5.3.19 – 5.3.20 Women 5.3.21 – 5.3.32 Children 5.3.33 – 5.3.36 Trafficking in Women and Children 5.3.37 – 5.3.39 5.4 OTHER ISSUES Assembly and Association 5.4.1 – 5.4.3 Speech and Press 5.4.4 – 5.4.5 Travel 5.4.6 Chittagong Hill Tracts 5.4.7 – 5.4.10 Student Organizations 5.4.11 – 5.4.12 Prosecution of 1975 Coup Leaders 5.4.13 Domestic Servants 5.4.14 – 5.4.15 Prison Conditions 5.4.16 – 5.4.18 ANNEX A: POLITICAL ORGANIZATIONS AND OTHER GROUPS ANNEX B: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX C: CHRONOLOGY ANNEX D: BIBLIOGRAPHY III HISTORY 3.2 East Pakistan became dissatisfied with the distant central government in West Pakistan, and the situation was exacerbated in 1952 when Urdu was declared Pakistan's official language. -

MSM Monograph-8.Qxd

Publications from Avahan in this series Avahan—The India AIDS Initiative: The Business of HIV Prevention at Scale Off the Beaten Track: Avahan’s Experience in the Business of HIV Prevention among India’s Long-Distance Truckers Use It or Lose It: How Avahan Used Data to Shape Its HIV Prevention Efforts in India Managing HIV Prevention from the Ground Up: Avahan’s Experience with Peer Led Outreach at Scale in India Peer Led Outreach at Scale: A Guide to Implementation The Power to Tackle Violence: Avahan’s Experience with Community Led Crisis Response in India Community Led Crisis Response Systems: A Guide to Implementation From Hills to Valleys: Avahan's HIV Prevention Program among Injecting Drug Users in Northeast India Treat and Prevent: Avahan’s Experience in Scaling Up STI Services to Groups at High Risk of HIV Infection in India Breaking Through Barriers: Avahan’s Scale-Up of HIV Prevention among High-Risk MSM and Transgenders in India Also available at: www.gatesfoundation.org/avahan BREAKING THROUGH BARRIERS: Avahan’s Scale-Up of HIV Prevention among High-Risk MSM and Transgenders in India This publication was commissioned by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in India. We thank all who have worked tirelessly in the design and implementation of Avahan. We also thank James Baer who assisted in the writing and production of this publication. Version 1, June 2010 Citation: Breaking Through Barriers: Avahan's Scale-Up of HIV Prevention among High-Risk MSM and Transgenders in India. New Delhi: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, 2010. -

Role of the Muslim Anjumans for the Promotion of Education in the Colonial Punjab: a Historical Analysis

Bulletin of Education and Research December 2019, Vol. 41, No. 3 pp. 1-18 Role of the Muslim Anjumans for the Promotion of Education in the Colonial Punjab: A Historical Analysis Maqbool Ahmad Awan* __________________________________________________________________ Abstract This article highlightsthe vibrant role of the Muslim Anjumans in activating the educational revival in the colonial Punjab. The latter half of the 19th century, particularly the decade 1880- 1890, witnessed the birth of several Muslim Anjumans (societies) in the Punjab province. These were, in fact, a product of growing political consciousness and desire for collective efforts for the community-betterment. The Muslims, in other provinces, were lagging behind in education and other avenues of material prosperity. Their social conditions were also far from being satisfactory. Religion too had become a collection of rites and superstitions and an obstacle for their educational progress. During the same period, they also faced a grievous threat from the increasing proselytizing activities of the Christian Missionary societies and the growing economic prosperity of the Hindus who by virtue of their advancement in education, commerce and public services, were emerging as a dominant community in the province. The Anjumans rescued the Muslim youth from the verge of what then seemed imminent doom of ignorance by establishing schools and madrassas in almost all cities of the Punjab. The focus of these Anjumans was on both secular and religious education, which was advocated equally for both genders. Their trained scholars confronted the anti-Islamic activities of the Christian missionaries. The educational development of the Muslims in the Colonial Punjab owes much to these Anjumans. -

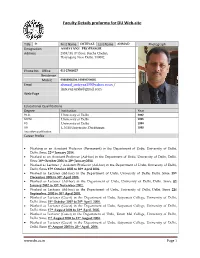

Faculty Details Proforma for DU Web-Site

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site Title Dr. First Name IMTEYAZ Last Name AHMAD Photograph Designation ASSISTANT PROFESSOR Address 2839/40, 4th floor, Kucha Chelan, Daryaganj, New Delhi. 110002. Phone No Office 011-27666627 Residence Mobile 09868008294 / 09899754685 Email [email protected] / [email protected] Web-Page Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. University of Delhi 2002 M.Phil. University of Delhi 1996 PG University of Delhi 1994 UG L.N.M.University, Darbhanga 1990 Any other qualification Career Profile Working as an Assistant Professor (Permanent) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 22nd January 2014. Worked as an Assistant Professor (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 16th October 2006 to 20th January2014. Worked as Lecturer / Assistant Professor (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 17th October 2005 to 30th April 2006. Worked as Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 28th December 2004 to 30th April 2005. Worked as Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 8th January 2002 to 15th November 2002. Worked as Lecturer (Ad-hoc) in the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 21st September. 2000 to 30th April 2001. Worked as Lecturer (Guest) in the Department of Urdu, Satyawati College, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 31st October 2007 to 20th April. 2008. Worked as Lecturer (Guest) in the Department of Urdu, Satyawati College, University of Delhi, Delhi. Since 17th August 2004 to 23rd April. -

Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology

Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology Merit List Department of Arabic (Bachelors, Morning) 2020 Abdul Haq Campus S# Form No Name Father Percent 1 202764 RABIAA MUHAMMAD AMIN 91.18 2 202095 NOORULAIN MUHAMMAD RAFIQ 67.27 3 205559 NASIR HUSSAIN KHUDA YAR 61.69 4 206180 ATA UR REHMAN ZAKIR UR REHMAN 54.22 Note: This list is conditional (Subjected to approval of Prof. Dr. Muhammad Zahid Concern Department and Varification of Documents). (Director Admission) Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology Merit List Department of Education (B.Ed 2.5 Years) (Bachelors, Morning) 2020 Abdul Haq Campus S# Form No Name Father Percent 1 204745 BUSHRA SAMI MUHAMMAD SAMI 78.34 2 204747 RUBAB SAMI MUHAMMAD SAMI 78.21 3 206250 SYED HASSNAN SYED MUHAMMAD SHAH 69.70 4 207469 MUHAMMAD AFTAB SARWAR MUHAMMAD SARWAR MALIK 68.67 5 205695 ALTAF AHMED MUHAMMAD MUNSIF 66.68 6 206100 MUHAMMAD FAIZAN MUHAMMAD IMRAN 66.38 7 200210 RAFIA FAROOQ MUHAMMAD FAROOQ 65.13 8 203771 NIMRAH AFTAB AFTAB AHMED 62.42 9 206939 MARINA RIAZ AHMED 61.70 10 203927 NUSRAT JABEEN DEEN MUHAMMAD 61.50 11 207432 BISMA MUHAMMAD YOUSUF BALOCH 60.69 12 202584 SEHRISH MUHAMMAD RIAZ 60.10 13 206963 HAYAT KHATOON KORAI MAZHAR UL HAQUE 60.00 14 202094 HUMAIRA MUHAMMAD KHAN 57.20 15 206719 ABDUL SAMAD MUHAMMAD RIAZ 56.36 16 206127 NAZIA MUHAMMAD YOUNUS 56.25 Note: This list is conditional (Subjected to approval of Prof. Dr. Muhammad Zahid Concern Department and Varification of Documents). (Director Admission) Federal Urdu University of Arts, Science & Technology Merit List -

Claiming Territory: Colonial State Space and the Making of British India’S North-West Frontier

CLAIMING TERRITORY: COLONIAL STATE SPACE AND THE MAKING OF BRITISH INDIA’S NORTH-WEST FRONTIER A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science by Jason G. Cons January 2005 © 2005 Jason G. Cons ABSTRACT In this thesis, I examine the discursive construction of colonial state space in the context of British India’s turn of the century North-West Frontier. My central argument is that notions of a uniform state space posited in official theorizations of the frontier need to be reexamined not as evidence of a particular kind of rule, but rather as a claim to having accomplished it. Drawing on new colonial historiographies that suggest ways of reading archives and archival documents for their silences and on historical sociological understandings of state-formation, I offer close readings of three different kinds of documents: writing about the North-West Frontier by members of the colonial administration, annual general reports of the Survey of India, and narratives written by colonial frontier officers detailing their time and experience of “making” the frontier. I begin by looking at the writings of George Nathanial Curzon and others attempting to theorize the concept of frontiers in turn of the century political discourse. Framed against the backdrop of the “Great Game” for empire with Russia and the progressive territorial consolidation of colonial frontiers into borders in the late 19th century, these arguments constitute what I call a “colonial theory of frontiers.” This theory simultaneously naturalizes colonial space and presents borders as the inevitable result of colonial expansion. -

The Challenges of Institutionalising Democracy in Bangladesh† Rounaq Jahan∗ Columbia University

ISAS Working Paper No. 39 – Date: 6 March 2008 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg The Challenges of Institutionalising † Democracy in Bangladesh Rounaq Jahan∗ Columbia University Contents Executive Summary i-iii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Challenges of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: A Global Discourse 4 3. The Challenge of Organising Free and Fair Elections 7 4. The Challenge of Establishing the Rule of Law 19 5. The Challenge of Guaranteeing Civil Liberties and Fundamental Freedoms 24 6. The Challenge of Ensuring Accountability 27 7. Conclusion 31 Appendix: Table 1: Results of Parliamentary Elections, February 1991 34 Table 2: Results of Parliamentary Elections, June 1996 34 Table 3: Results of Parliamentary Elections, October 2001 34 Figure 1: Rule of Law, 1996-2006 35 Figure 2: Political Stability and Absence of Violence, 1996-2006 35 Figure 3: Control of Corruption, 1996-2006 35 Figure 4: Voice and Accountability, 1996-2006 35 † This paper was prepared for the Institute of South Asian Studies, an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore. ∗ Professor Rounaq Jahan is a Senior Research Scholar at the Southern Asian Institute, School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University. She can be contacted at [email protected]. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Bangladesh joined what Samuel P. Huntington had called the “third wave of democracy”1 after a people’s movement toppled 15 years of military rule in December 1990. In the next 15 years, the country made gradual progress in fulfilling the criteria of a “minimalist democracy”2 – regular free and contested elections, peaceful transfer of governmental powers as a result of elections, fundamental freedoms, and civilian control over policy and institutions.