Claiming Territory: Colonial State Space and the Making of British India’S North-West Frontier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism

Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review 51 | 2016 Global History, East Africa and The Classical Traditions Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism Phiroze Vasunia Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/314 Publisher IFRA - Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique Printed version Date of publication: 1 March 2016 Number of pages: 21-43 ISSN: 2071-7245 Electronic reference Phiroze Vasunia, « Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism », Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review [Online], 51 | 2016, Online since 07 May 2019, connection on 08 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/314 Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review Global History, East Africa and the Classical Traditions. Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism Phiroze Vasunia Can the Ethiopian change his skinne? or the leopard his spots? Jeremiah 13.23, in the King James Version (1611) May a man of Inde chaunge his skinne, and the cat of the mountayne her spottes? Jeremiah 13.23, in the Bishops’ Bible (1568) I once encountered in Sicily an interesting parallel to the ancient confusion between Indians and Ethiopians, between east and south. A colleague and I had spent some pleasant moments with the local custodian of an archaeological site. Finally the Sicilian’s curiosity prompted him to inquire of me “Are you Chinese?” Frank M. Snowden, Blacks in Antiquity (1970) The ancient confusion between Ethiopia and India persists into the late European Enlightenment. Instances of the confusion can be found in the writings of distinguished Orientalists such as William Jones and also of a number of other Europeans now less well known and less highly regarded. -

An Indian Englishman

AN INDIAN ENGLISHMAN AN INDIAN ENGLISHMAN MEMOIRS OF JACK GIBSON IN INDIA 1937–1969 Edited by Brij Sharma Copyright © 2008 Jack Gibson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted by any means—whether auditory, graphic, mechanical, or electronic—without written permission of both publisher and author, except in the case of brief excerpts used in critical articles and reviews. Unauthorized reproduction of any part of this work is illegal and is punishable by law. ISBN: 978-1-4357-3461-6 Book available at http://www.lulu.com/content/2872821 CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction 1 To The Doon School 5 Bandarpunch-Gangotri-Badrinath 17 Gulmarg to the Kumbh Mela 39 Kulu and Lahul 49 Kathiawar and the South 65 War in Europe 81 Swat-Chitral-Gilgit 93 Wartime in India 101 Joining the R.I.N.V.R. 113 Afloat and Ashore 121 Kitchener College 133 Back to the Doon School 143 Nineteen-Fortyseven 153 Trekking 163 From School to Services Academy 175 Early Days at Clement Town 187 My Last Year at the J.S.W. 205 Back Again to the Doon School 223 Attempt on ‘Black Peak’ 239 vi An Indian Englishman To Mayo College 251 A Headmaster’s Year 265 Growth of Mayo College 273 The Baspa Valley 289 A Half-Century 299 A Crowded Programme 309 Chini 325 East and West 339 The Year of the Dragon 357 I Buy a Farm-House 367 Uncertainties 377 My Last Year at Mayo College 385 Appendix 409 PREFACE ohn Travers Mends (Jack) Gibson was born on March 3, 1908 and J died on October 23, 1994. -

Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan

Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan Ideas, Issues and Questions of Nation-Building in Pakistan Research Cooperation between the Hanns Seidel Foundation Pakistan and the Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad Islamabad, 2020 Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan Edited by Sarah Holz Ideas, Issues and Questions of Nation-Building in Pakistan Research Cooperation between Hanns Seidel Foundation, Islamabad Office and Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan Acknowledgements Thank you to Hanns Seidel Foundation, Islamabad Office for the generous and continued support for empirical research in Pakistan, in particular: Kristóf Duwaerts, Omer Ali, Sumaira Ihsan, Aisha Farzana and Ahsen Masood. This volume would not have been possible without the hard work and dedication of a large number of people. Sara Gurchani, who worked as the research assistant of the collaboration in 2018 and 2019, provided invaluable administrative, organisational and editorial support for this endeavour. A big thank you the HSF grant holders of 2018 who were not only doing their own work but who were also actively engaged in the organisation of the international workshop and the lecture series: Ibrahim Ahmed, Fateh Ali, Babar Rahman and in particular Adil Pasha and Mohsinullah. Thank you to all the support staff who were working behind the scenes to ensure a smooth functioning of all events. A special thanks goes to Shafaq Shafique and Muhammad Latif sahib who handled most of the coordination. Thank you, Usman Shah for the copy editing. The research collaboration would not be possible without the work of the QAU faculty members in the year 2018, Dr. Saadia Abid, Dr. -

Survey of Predatory Coccinellids (Coleoptera

Survey of Predatory Coccinellids (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) in the Chitral District, Pakistan Author(s): Inamullah Khan, Sadrud Din, Said Khan Khalil and Muhammad Ather Rafi Source: Journal of Insect Science, 7(7):1-6. 2007. Published By: Entomological Society of America DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1673/031.007.0701 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1673/031.007.0701 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Journal of Insect Science | www.insectscience.org ISSN: 1536-2442 Survey of predatory Coccinellids (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) in the Chitral District, Pakistan Inamullah Khan, Sadrud Din, Said Khan Khalil and Muhammad Ather Rafi1 Department of Plant Protection, NWFP Agricultural University, Peshawar, Pakistan 1 National Agricultural Research Council, Islamabad, Pakistan Abstract An extensive survey of predatory Coccinellid beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) was conducted in the Chitral District, Pakistan, over a period of 7 months (April through October, 2001). -

The Keys to British Success in South Asia COLIN WATTERSON

The Keys to British Success in South Asia COLIN WATTERSON “God is on everyone’s side…and in the last analysis he is on the side with plenty of money and large armies” -Jean Anouilh For a period of a period of over one hundred years, the British directly controlled the subcontinent of India. How did a small island nation come on the Edge of the North Atlantic come to dominate a much larger landmass and population located almost 4000 miles away? Historian Sir John Robert Seeley wrote that the British Empire was acquired in “a fit of absence of mind” to show that the Empire was acquired gradually, piece-by-piece. This will paper will try to examine some of the most important reasons which allowed the British to successfully acquire and hold each “piece” of India. This paper will examine the conditions that were present in India before the British arrived—a crumbling central political power, fierce competition from European rivals, and Mughal neglect towards certain portions of Indian society—were important factors in British control. Economic superiority was an also important control used by the British—this paper will emphasize the way trade agreements made between the British and Indians worked to favor the British. Military force was also an important factor but this paper will show that overwhelming British force was not the reason the British military was successful—Britain’s powerful navy, ability to play Indian factions against one another, and its use of native soldiers were keys to military success. Political Agendas and Indian Historical Approaches The historiography of India has gone through four major phases—three of which have been driven by the prevailing world politics of the time. -

Constituent Assembly Debates Official Report

Volume VII 4-11-1948 to 8-1-1949 CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY DEBATES OFFICIAL REPORT REPRINTED BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI SIXTH REPRINT 2014 Printed by JAINCO ART INDIA, New Delhi CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA President : THE HONOURABLE DR. RAJENDRA PRASAD Vice-President : DR. H.C. MOOKHERJEE Constitutional Adviser : SIR B.N. RAU, C.I.E. Secretary : SHRI H.V. IENGAR, C.I.E., I.C.S. Joint Secretary : SHRI S.N. MUKERJEE Deputy Secretary : SHRI JUGAL KISHORE KHANNA Under Secretary : SHRI K.V. PADMANABHAN Marshal : SUBEDAR MAJOR HARBANS RAI JAIDKA CONTENTS ————— Volume VII—4th November 1948 to 8th January 1949 Pages Pages Thursday, 4th November 1948 Thursday, 18th November, 1948— Presentation of Credentials and Taking the Pledge and Signing signing the Register .................. 1 the Register ............................... 453 Taking of the Pledge ...................... 1 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 453—472 Homage to the Father of the Nation ........................................ 1 [Articles 3 and 4 considered] Condolence on the deaths of Friday, 19th November 1948— Quaid-E-Azam Mohammad Ali Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 473—500 Jinnah, Shri D.P. Khaitan and [Articles 28 to 30-A considered] Shri D.S. Gurung ...................... 1 Amendments to Constituent Monday, 22nd November 1948— Assembly Rules 5-A and 5-B .. 2—12 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 501—527 Amendment to the Annexure to the [Articles 30-A, 31 and 31-A Schedule .................................... 12—15 considered] Addition of New Rule 38V ........... 15—17 Tuesday, 23rd November 1948— Programme of Business .................. 17—31 Draft Constitution—(contd.) ........... 529—554 Motion re Draft Constitution ......... 31—47 Appendices— [Articles 32, 33, 34, 34-A, 35, 36, 37 Appendix “A” ............................. -

GOVERNMENT of PAKISTAN NATIONAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY MONSOON WEATHER SITUATION REPORT 2015 DATED: 23Rd JULY 2015

GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN NATIONAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY MONSOON WEATHER SITUATION REPORT 2015 DATED: 23rd JULY 2015 RIVERS RESERVOIRS (Reading 0600hrs) LOSSES / DAMAGES MAX Conservation Actual Observations RESERVOIR Today (Feet) Design Forecast for Forecasted Level (Feet) River / Capacity In Flow Out Flow Next 24hrs Flood Level Structure Tarbela 1,550.00 1530.00 (Cusecs) (thousand (thousand (Inflow) (Inflow) cusecs) cusecs) Mangla 1,242.00 1234.90 RIVER INDUS (Reading 0600hrs) RAINFALL (MM) PAST 24 HOURS Chitral Flash Flood / GLOF - Annex A Tarbela 1,500,000 340.0 178.6 330 – 350 Low Balakot 96 Rawalakot 39 Talhatta 24 Punjab Riverine Flood - Annex B Medium – Palku, Domel & Kalabagh 950,000 397.1 388.8 380 F 290 Palandri 84 Ura 32 23 Low Malamjabba Balochistan Flash Flood - Annex C Medium - Gilgit Baltistan Flash Flood / GLOF - Annex D Chashma 950,000 469.8 462.8 460 F 360 Kakul 68 Shinkiari 28 Pattan 20 Low Sindh Precautionary Measures – Annex E Chattar Kallass & Taunsa 1,100,000 457.7 457.7 445 – 455 Medium Muzaffarabad 61 Oghi & Lasbela 26 15 NHA Road Network Sitrep - Annex F Khuzdar Guddu 1,200,000 396.1 370.0 400 R 470 Medium Sehrkakota 57 Dir 25 Murree & Sibbi 13 Sukkur 1,500,000 295.2 242.4 300 – 330 Low Kotli 54 Sialkot (Cantt) 25 Dratian 12 Tanda Dam & Kotri 875,000 107.8 80.6 110 – 120 Below Low Peshawar (AP) 43 Sialkot (AP) 01 11 Garhidupatta RIVER KABUL (Reading 0600hrs) METEOROLOGICAL FEATURES NOTES Nowshera - 79.5 79.5 75 – 85 Medium WEATHER WARNING Yesterday’s trough of westerly wave over upper parts of the RIVER JHELUM (Reading 0600hrs) country today lies over Kashmir and adjoining areas. -

Abstracts in Alphabetical Order

Abstracts in alphabetical order “They are taking our land”: a comparative perspective on indigeneity and alterity in Meghalaya and the Chittagong Hill Tracts Ellen Bal (VU University Amsterdam) & Eva Gerharz (Ruhr‐University Bochum) The border region of Bangladesh, India, and Burma has been the scene of dozens of tribal autonomy conflicts since the independence of India and Pakistan in 1947 (Baruah 2007). These conflicts have unsettled the whole region, impacted international relations, threatened national stability, and caused a deep sense of insecurity among the locals. The majority of these conflicts pivot on ‘sons‐of‐the-soil’ claims, invoking notions of autochthony to legitimize occupational rights to lands and regional autonomy (Cf. Vandekerckhove 2009). Most conflicts link up to the globalized discourse on indigenous rights, which has been particularly powerful since 1993 (the United Nations’ ‘Year for Indigenous Peoples’). Our paper addresses the notions of citizenship, indigeneity and alterity (otherness) at work in Meghalaya and the Chittagong Hill Tracts from a comparative perspective. Although a number of similar issues are at stake, the situations in the two regions differ, partly because of different political contexts which frame these discourses. British colonial policies had been geared towards the isolation of the hills from the plains in order to secure the available resources for the colonial state (Van Schendel 1992). Independent India continued such particularistic policies, granting a special position to the so‐called tribal Northeast Indian hill states (Vandekerckhove 2009, 53). However, the subsequent governments of Pakistan and Bangladesh (since 1971) moved towards inclusion of the tribal territories. In the Chittagong Hill Tracts this attempt of national inclusion resulted in a vicious war between indigenous insurgents and the state. -

Are the Kalasha Really of Greek Origin? the Legend of Alexander the Great and the Pre-Islamic World of the Hindu Kush1

Acta Orientalia 2011: 72, 47–92. Copyright © 2011 Printed in India – all rights reserved ACTA ORIENTALIA ISSN 0001-6483 Are the Kalasha really of Greek origin? The Legend of Alexander the Great and the Pre-Islamic World of the Hindu Kush1 Augusto S. Cacopardo Università di Firenze Abstract The paper refutes the claim that the Kalasha may be the descendants of the Greeks of Asia. First, traditions of Alexandrian descent in the Hindu Kush are examined on the basis of written sources and it is shown that such legends are not part of Kalasha traditional knowledge. Secondly, it is argued that the Kalasha were an integral part of the pre-Islamic cultural fabric of the Hindu Kush, and cannot be seen as intruders in the area, as legends of a Greek descent would want them. Finally, through comparative suggestions, it is proposed that possible similarities between the Kalasha and pre-Christian 1 Paper presented as a key-note address at the First International Conference on Language Documentation and Tradition, with a Special Interest in the Kalasha of the Hindu Kush Valleys, Himalayas – Thessaloniki, Greece, 7–9 November 2008. Scarcity of funds caused the scientific committee to decide to select for the forthcoming proceedings only linguistic papers. This is rather unfortunate because the inclusion in the volume of anthropological papers as well would have offered a good opportunity for comparing different views on the question of the Greek ascendancy of the Kalasha. 48 Augusto S. Cacopardo Europe are to be explained by the common Indo-European heritage rather than by more recent migrations and contacts. -

Religion and Geography

Park, C. (2004) Religion and geography. Chapter 17 in Hinnells, J. (ed) Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion. London: Routledge RELIGION AND GEOGRAPHY Chris Park Lancaster University INTRODUCTION At first sight religion and geography have little in common with one another. Most people interested in the study of religion have little interest in the study of geography, and vice versa. So why include this chapter? The main reason is that some of the many interesting questions about how religion develops, spreads and impacts on people's lives are rooted in geographical factors (what happens where), and they can be studied from a geographical perspective. That few geographers have seized this challenge is puzzling, but it should not detract us from exploring some of the important themes. The central focus of this chapter is on space, place and location - where things happen, and why they happen there. The choice of what material to include and what to leave out, given the space available, is not an easy one. It has been guided mainly by the decision to illustrate the types of studies geographers have engaged in, particularly those which look at spatial patterns and distributions of religion, and at how these change through time. The real value of most geographical studies of religion in is describing spatial patterns, partly because these are often interesting in their own right but also because patterns often suggest processes and causes. Definitions It is important, at the outset, to try and define the two main terms we are using - geography and religion. What do we mean by 'geography'? Many different definitions have been offered in the past, but it will suit our purpose here to simply define geography as "the study of space and place, and of movements between places". -

Inaugural British Narration

! ! ! The American University! in Cairo School of Global Affairs! and Public Policy ! ! ! Resurrecting Eden: Inaugural British Narration! and Policy of Iraq ! ! ! A Thesis Submitted to the Middle East! Studies Center ! in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (M.A.)! in Middle East Studies ! ! ! by Timothy! Kennett ! ! ! under the supervision !of Dr. Walid Kazziha ! ! ! May !2015 ! ! © Copyright by Timothy Kennett 2015 All rights reserved ! The American University! in Cairo School of Global Affairs !& Public Policy (GAPP) Resurrecting Eden: ! Inaugural British Narration and Policy of Iraq ! A Thesis Submitted! by Timothy !Kennett ! to the Middle East! Studies Center May, !2015 In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The degree of Master of Arts in Middle East! Studies ! has been approved! by Dr. Walid Kazziha ____________________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor !Affiliation __________________________________________Date ____________ Dr. Sherene Seikaly ___________________________________________________ Thesis first Reader !Affiliation __________________________________________Date ____________ Dr. Marco Pinfari _____________________________________________________ Thesis Second Reader !Affiliation __________________________________________Date ____________ Dr. Sandrine Gamblin _________________________________________________ Department Chair !Date ____________________ Nabil Fahmy, Ambassador _______________________________________________ Dean of GAPP Date ____________________ -

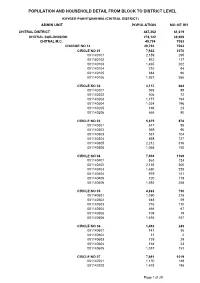

Chitral Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (CHITRAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH CHITRAL DISTRICT 447,362 61,619 CHITRAL SUB-DIVISION 278,122 38,909 CHITRAL M.C. 49,794 7063 CHARGE NO 14 49,794 7063 CIRCLE NO 01 7,933 1070 001140101 2,159 295 001140102 972 117 001140103 1,465 202 001140104 716 94 001140105 684 96 001140106 1,937 266 CIRCLE NO 02 4,157 664 001140201 593 89 001140202 505 72 001140203 1,171 194 001140204 1,024 196 001140205 198 23 001140206 666 90 CIRCLE NO 03 5,875 878 001140301 617 85 001140302 569 96 001140303 551 104 001140304 858 127 001140305 2,212 316 001140306 1,068 150 CIRCLE NO 04 7,939 1169 001140401 863 124 001140402 2,135 300 001140403 1,650 228 001140404 979 141 001140405 720 118 001140406 1,592 258 CIRCLE NO 05 4,883 730 001140501 1,590 218 001140502 448 59 001140503 776 110 001140504 466 67 001140505 109 19 001140506 1,494 257 CIRCLE NO 06 1,492 243 001140601 141 36 001140602 11 2 001140603 139 29 001140604 164 23 001140605 1,037 153 CIRCLE NO 07 7,691 1019 001140701 1,170 149 001140702 1,478 195 Page 1 of 29 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (CHITRAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 001140703 1,144 156 001140704 1,503 200 001140705 1,522 196 001140706 874 123 CIRCLE NO 08 9,824 1290 001140801 2,779 319 001140802 1,605 240 001140803 1,404 200 001140804 1,065 152 001140805 928 124 001140806 974 135 001140807 1,069 120 CHITRAL TEHSIL 228,328 31846 ARANDU UC 23,287 3105 AKROI 1,777 301 001010105 1,777 301 ARANDU