Hoover Digest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stanford Daily an Independent Newspaper

The Stanford Daily An Independent Newspaper VOLUME 199, NUMBER 36 99th YEAR MONDAY, APRIL 15, 1991 Electronic mail message may be bylaws violation By Howard Libit Staff writer Greek issues Over the weekend, campaign violations seemed to be the theme of the Council of Presidents and addressed in ASSU Senate races. Hearings offi- cer Jason Moore COP debate said the elec- By MirandaDoyle tions commis- Staff writer sion will look into vio- possible Three Council of Presi- lations by Peo- dents slates debated at the pie's Platform Sigma house last candidatesand their supporters of Kappa night, answering questions several election bylaws that ranging from policies revolve around campaigning toward Greek organizations through electronic mail. to the scope ofASSU Senate Students First also complained debate. about the defacing and removing Beth of their fliers. The elec- Morgan, a Students of some First COP said will be held Wednesday and candidate, tion her slate plans to "fight for Thursday. new houses to be built" for Senate candidate Nawwar Kas- senate fraternities and work on giv- rawi, currently a associate, ing the Interfraternity sent messages yesterday morning Council and the Intersoror- to more than 2,000 students via ity Council more input in electronic urging support for mail, decisions concerning frater- the People's Platform COP Rajiv Chandrasekaran — Daily "Stand and Deliver" senate nities and sororities. First lady Barbara Bush was one of many celebrities attending this weekend's opening ceremonies for the Lucile Salter Packard Chil- slate, member ofthe candidates and several special fee MaeLee, a dren's Hospital. She took time out from a tour of the hospital to meet two patients, Joshua Evans, 9, and Shannon Brace, 4. -

HBO's Vinyl Revisits the Golden Age of Rock

THEY WILL ROCK Photo by Niko Tavernise/HBO Photo by Niko YOU HBO’s Vinyl revisits the golden age of rock ‘n’ roll By Joe Nazzaro oardwalk Empire creators Terence Winter and Martin Scorsese team up with veteran rocker Mick Jagger (who Boriginally conceived the idea of a show two decades ago) for the new HBO drama Vinyl. It’s about music executive Richie Finestra (played by Bobby Cannavale) trying to run a successful business amid the fast-changing 1970s music scene. “The whole project takes place in 1973 New York,” explains make-up department head Nicki Ledermann, who won an Emmy for her work on the Boardwalk Empire pilot. “It’s about a record label owner and his experiences with the music industry, but we also have flashbacks back to Andy Warhol in the 1960s, as well as scenes set in the 1950s. Bobby Cannavale as Richie Finestra 96 MAKE-UP ARTIST NUMBER 119 MAKEUPMAG.COM 97 “THERE WAS ... A FUN AND EXPERIMENTAL EVOLUTION HAPPENING WITH THE BEAUTY MAKE-UP IN THE '70S.” —NICKI LEDERMANN “What’s cool about this show is it’s not just about punk rock; it’s about the start of it and how it started to evolve. We have every musical genre in this show, which makes it even more appealing, because we have all this good stuff from every type of music, from soul to blues to rock and roll to the early punk music. “There are fictional bands in the series, as well as people who really existed, so we have Alice Cooper and David Bowie, and some cool flashbacks to soul singers like Tony Bennett and Ruth Brown.” And there is no shortage of iconic styles in the series, from the outrageous to the glamorous. -

New Public Diplomacy Has Only Just Begun

Make an impact. communication Ph.D./ M.A. communication management M.C.M. global communication M.A./ MSc public diplomacy M.P.D. journalism M.A. – PRINT/BROADCAST/ONLINE specialized journalism M.A. specialized journalism (the arts) M.A. strategic public relations M.A. U S C A N N E N B E R G S C H O O L F O R C O M M U N I C A T I O N • Ranked among the top communication and journalism programs in the United States • Extensive research and networking opportunities on campus and in the surrounding communities of Los Angeles • Learner-centered pedagogy with small classes, strong student advising and faculty mentoring • State-of-the-art technology and on-campus media outlets • Energetic and international student body • Social, historical and cultural approaches to communication annenberg.usc.edu The graduate education you want. The graduate education you need. The University of Southern California admits students of any race, color, and national or ethnic origin. Public Diplomacy (PD) Editor-in-Chief Anoush Rima Tatevossian Managing Editor Desa Philadelphia Senior Issue Editor Lorena Sanchez Staff Editors: Noah Chestnut, Hiva Feizi, Tala Mohebi, Daniela Montiel, John Nahas, Paul Rockower, Leah Rousseau Production Leslie Wong, Publication Designer, [email protected] Colin Wright, Web Designer, colin is my name, www.colinismyname.com Faculty Advisory Board Nick Cull, Director, USC’s Public Diplomacy Master’s Program Phil Seib, Professor of Journalism and Public Diplomacy, USC Geoff Wiseman, Director, USC Center on Public Diplomacy Ex-Officio -

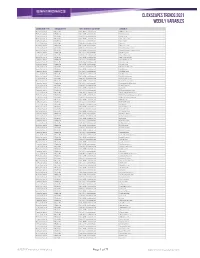

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

Strategies Xxi the Complex and Dynamic Nature of The

“CAROL I” NATIONAL DEFENCE UNIVERSITY Centre for Defence and Security Strategic Studies THE INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC CONFERENCE STRATEGIES XXI With the theme: THE COMPLEX AND DYNAMIC NATURE OF THE SECURITY ENVIRONMENT NOVEMBER 22-23, 2012, BUCHAREST Coordinators: Alexandra SARCINSCHI, PhD Cristina BOGZEANU “CAROL I” NATIONAL DEFENCE UNIVERSITY PUBLISHINGHOUSE BUCHAREST, 2012 SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE - Teodor FRUNZETI, PhD. prof., “Carol I” National Defence University, Romania - Ion ROCEANU, PhD. prof., “Carol I” National Defence University, Romania - Petre DUŢU, senior researcher PhD., “Carol I” National Defence University, Romania - Bogdan AURESCU, PhD. lecturer, University of Bucharest, Romania - Silviu NEGUŢ, PhD. prof., Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies, Romania - Rudolf URBAN, PhD. prof., Defence University, Czech Republic - Pavel NECAS, PhD. prof. dipl. eng., Armed Forces Academy, Slovakia - Alexandra SARCINSCHI, senior researcher PhD., “Carol I” National Defence University, Romania - Cristian BĂHNĂREANU, senior researcher PhD., “Carol I” National Defence University, Romania - Mihai-Ştefan DINU, senior researcher PhD., “Carol I” National Defence University, Romania - Cristina BOGZEANU, junior researcher, “Carol I” National Defence University, Romania ADMINISTRATIVE COMMITTEE - Petre DUŢU senior researcher PhD. - Irina TĂTARU, PhD. - Mirela ATANASIU, PhD. - George RĂDUICĂ, PhD. - Daniela RĂPAN - Doina MIHAI - Marioara PETRE-BĂJENARU COPYRIGHT: Any reproduction is authorized, without fees, provided that the source is mentioned. • -

Chownow on How Independent Eateries Can Navigate Pandemic-Related Challenges

DECEMBER 2020 FEATURE STORY (p . 7) ChowNow On How Independent Eateries Can Navigate Pandemic-Related News and Trends Deep Dive Scorecard QSR transactions drop The fraud trends The latest mobile Challenges 11by 9 percent year over 17of 2020 and what 21order-ahead provider year in October due to restaurants can rankings decreased dine-in traffic learn from them TABLE OF CONTENTS What's Inside A look at recent mobile order-ahead developments, including the fraud trends 3 brought about or aggravated by the pandemic and how they could shape QSRs’ security measures in the years to come Feature Story An interview with co-founder and COO Eric Jaffe of online food ordering system 7 ChowNow about the struggles independent restaurants faced in 2020 and the fraud lessons they will take into the future News and Trends The latest mobile order-ahead developments, including how restaurants lost $117 million to social media scams during the first half of 2020 and how QSRs’ 11 transaction volumes declined by 9 percent in October compared to the same month during the previous year Deep Dive An in-depth examination of 2020 fraud trends as well as the lessons QSRs must 17 learn from new fraud schemes as they enter the new year Scoring Methodology 20 Who’s on top and how they got there Top 10 Providers and Scorecard The results are in. See the top scorers and a provider directory that features 77 21 players in the space About Information on PYMNTS.com and Kount ACKNOWLEDGMENT 51 ® The Mobile Order-Ahead Tracker is done in collaboration with Kount, and PYMNTS is grateful for the company’s support and insight. -

Resy Reopening Playbook

Rebuilding with Resy ©2021 RESY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Introduction As we start to see the glimmers of hope and light at the end of a very difficult year, we’re excited to join you in welcoming guests back to your restaurant. From our inception, Resy was designed to be more than a platform - we’re your partners. With fee relief extended through June 2021, we are committed to supporting the industry through this period of uncertainty and change. While your guest experience may look very different from before COVID-19, we’re here to help you navigate the new normal. By restaurants, for restaurants. How To Use This Playbook With restaurants across the world in various phases of reopening, we’ve designed this playbook to be useful for businesses at any stage. From fine dining operations who are just starting the process of turning on reservations again, to cafes with outdoor seating looking for additional revenue sources, this guide has something for everyone. In this playbook, you’ll find the steps to: 1 Restart reservations and table management using Resy OS 2 Train new staff and provide a refresh on Resy OS for legacy employees 3 Market your return to the community 4 Maximize operations with new Resy OS features 5 Increase revenue through takeout and events 6 Update your technology with exclusive offers Table of Contents Page 05 The Essentials: Steps to Take Before Opening Reservations Page 08 Reopening Checklist Page 09 Communication and Marketing Strategies: Making The Most Of Your Reopening Page 13 Training Resources: Level Up Your Resy -

A Schema of Right-Wing Extremism in the United States

ICCT Policy Brief October 2019 DOI: 10.19165/2019.2.06 ISSN: 2468-0486 A Schema of Right-Wing Extremism in the United States Author: Sam Jackson Over the past two years, and in the wake of deadly attacks in Charlottesville and Pittsburgh, attention paid to right-wing extremism in the United States has grown. Most of this attention focuses on racist extremism, overlooking other forms of right-wing extremism. This article presents a schema of three main forms of right-wing extremism in the United States in order to more clearly understand the landscape: racist extremism, nativist extremism, and anti-government extremism. Additionally, it describes the two primary subcategories of anti-government extremism: the patriot/militia movement and sovereign citizens. Finally, it discusses whether this schema can be applied to right-wing extremism in non-U.S. contexts. Key words: right-wing extremism, racism, nativism, anti-government A Schema of Right-Wing Extremism in the United States Introduction Since the public emergence of the so-called “alt-right” in the United States—seen most dramatically at the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017—there has been increasing attention paid to right-wing extremism (RWE) in the United States, particularly racist right-wing extremism.1 Violent incidents like Robert Bowers’ attack on the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in October 2018; the mosque shooting in Christchurch, New Zealand in March 2019; and the mass shooting at a Walmart in El Paso, Texas in August -

GES 2020 SENT 10Th TEMPLATE for SPEAKERS BIOS PP NOV. 1-12-20 VER 10

Simos Anastasopoulos is a graduate of the Department of Electrical Engineering of the National Technical University of Athens (NTUA), and holds a Master’s of Science Degree in Mechanical/Automotive Engineering from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He has worked for two years for General Motors Corporation as a development Engineer at the Milford Proving Ground. Since 2002 he had Been the Managing Director of the company and in 2013 was named Chairman and CEO of PETSIAVAS S.A. Since July 2020, he is President of Associations of S.A. & Limited LiaBility Companies. He is the elected President of the Council on Competitiveness of Greece, since its foundation in 2018. He is also a member of the Board of the Pan-Hellenic Association of Pharmaceutical Industries and a memBer of the General Council of SEV Hellenic Federation of Enterprises. Since June 2019, he is President Emeritus of Simos Anastasopoulos the American-Hellenic ChamBer of Commerce after a tenure of 6 years as the elected President. President Simos Anastasopoulos was Born in Athens in 1957, is married to Peggy Petsiavas and has two daughters. The Council on Competitiveness of Greece (CompeteGR) Born in 1961, Dimitris Andriopoulos has significant experience in the real estate, tourism, shipping and food industries. For more than 30 years he has been the head of major operations and projects in Greece and abroad for Intracom, Elliniki Technodomiki - Teb, Superfast Ferries and McDonald's. Since 2005 Mr. Dimitris Andriopoulos is the main shareholder and Chief Executive Officer of Dimand SA, an Athens based leading property and development company specializing in sustainable (LEED Gold) office developments and urban regeneration projects. -

February 12, 2019: SXSW Announces Additional Keynotes and Featured

SOUTH BY SOUTHWEST ANNOUNCES ADDITIONAL KEYNOTES AND FEATURED SPEAKERS FOR 2019 CONFERENCE Adam Horovitz and Michael Diamond of Beastie Boys, John Boehner, Kara Swisher, Roger McNamee, and T Bone Burnett Added to the Keynote Lineup Stacey Abrams, David Byrne, Elizabeth Banks, Aidy Bryant, Brandi Carlile, Ethan Hawke, Padma Lakshmi, Kevin Reilly, Nile Rodgers, Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss, and More Added as Featured Speakers Austin, Texas — February 12, 2019 — South by Southwest® (SXSW®) Conference and Festivals (March 8–17, 2019) has announced further additions to their Keynote and Featured Speaker lineup for the 2019 event. Keynotes announced today include former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives John Boehner with Acreage Holdings Chairman and CEO Kevin Murphy; a Keynote Conversation with Adam Horovitz and Michael Diamond of Beastie Boys with Amazon Music’s Nathan Brackett; award-winning producer, musician and songwriter T Bone Burnett; investor and author Roger McNamee with WIRED Editor in Chief Nicholas Thompson; and Recode co-founder and editor-at-large Kara Swisher with a special guest. Among the Featured Speakers revealed today are national political trailblazer Stacey Abrams, multi-faceted artist David Byrne; actress, producer and director Elizabeth Banks; actress, writer and producer Aidy Bryant; Grammy Award-winning musician Brandi Carlile joining a conversation with award-winning actress Elisabeth Moss; professional wrestler Charlotte Flair; -

Madhya Bharti 75 21.07.18 English

A Note on Paradoxes and Some Applications Ram Prasad At times thoughts in prints, dialogues, conversations and the likes create illusion among people. There may be one reason or the other that causes fallacies. Whenever one attempts to clear the illusion to get the logical end and is unable to, one may slip into the domain of paradoxes. A paradox seemingly may appear absurd or self contradictory that may have in fact a high sense of thought. Here a wide meaning of it including its shades is taken. There is a group of similar sensing words each of which challenges the wit of an onlooker. A paradox sometimes surfaces as and when one is in deep immersion of thought. Unprinted or oral thoughts including paradoxes can rarely survive. Some paradoxes always stay folded to gaily mock on. In deep immersion of thought W S Gilbert remarks on it in the following poetic form - How quaint the ways of paradox At common sense she gaily mocks1 The first student to expect great things of Philosophy only to suffer disillusionment was Socrates (Sokratez) -'what hopes I had formed and how grievously was I disappointed'. In the beginning of the twentieth century mathematicians and logicians rigidly argued on topics which appear possessing intuitively valid but apparently contrary statements. At times when no logical end is seen around and the topic felt hot, more on lookers would enter into these entanglements with argumentative approach. May be, but some 'wise' souls would manage to escape. Zeno's wraths - the Dichotomy, the Achilles, the Arrow and the Stadium made thinkers very uncomfortable all along. -

Local Restaurant, Retail and Service Providers

Local Restaurant, Retail and Service Providers As the coronavirus situation evolves and we move forward with daily life under new rules, our local grocery and pharmacy service providers continue to serve our community with adjusted operations and hours. Please see below for information about local grocery and pharmacy hours, meal and delivery services, restaurant and food bank updates and more. Please note all information is subject to change. LOCAL RESTAURANTS 19 Restaurant & Lounge • Address: 24122 Moulton Parkway • Telephone number: 949-206-1525 • Restaurant 19 is offering free delivery and to-go meals daily from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. and 4 to 7 p.m. Village residents can order at the restaurant or call. All hot dishes come in microwave containers. Daily specials are offered for multiple orders for two days’ worth of meals. View the menu here. BJ’s Restaurant • Address: 24032 El Toro Road • Telephone number: 949-900-2670 • BJ’s Restaurant offers free delivery for all orders over $19.95 through April 30 when placed online, or through the restaurant’s app. Chick-fil-A • Address: 24011 El Toro Road • Telephone number: 949-458-3544, press “1” • Chick-fil-A is rolling out free delivery to Laguna Woods Village residents who order a day in advance. The restaurant will deliver between 10 and 11 a.m. or between 4 and 5 p.m. For each regular order placed, Chick-fil-A will donate a meal to a senior in need. The Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf • Address: 24380 Moulton Parkway • Telephone number: 424-326-3007 • The drive-thru is open for pick-up orders with the ability to accommodate mobile app orders ahead of time.