An Analysis of Vice President Biden's Economic Agenda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stanford Daily an Independent Newspaper

The Stanford Daily An Independent Newspaper VOLUME 199, NUMBER 36 99th YEAR MONDAY, APRIL 15, 1991 Electronic mail message may be bylaws violation By Howard Libit Staff writer Greek issues Over the weekend, campaign violations seemed to be the theme of the Council of Presidents and addressed in ASSU Senate races. Hearings offi- cer Jason Moore COP debate said the elec- By MirandaDoyle tions commis- Staff writer sion will look into vio- possible Three Council of Presi- lations by Peo- dents slates debated at the pie's Platform Sigma house last candidatesand their supporters of Kappa night, answering questions several election bylaws that ranging from policies revolve around campaigning toward Greek organizations through electronic mail. to the scope ofASSU Senate Students First also complained debate. about the defacing and removing Beth of their fliers. The elec- Morgan, a Students of some First COP said will be held Wednesday and candidate, tion her slate plans to "fight for Thursday. new houses to be built" for Senate candidate Nawwar Kas- senate fraternities and work on giv- rawi, currently a associate, ing the Interfraternity sent messages yesterday morning Council and the Intersoror- to more than 2,000 students via ity Council more input in electronic urging support for mail, decisions concerning frater- the People's Platform COP Rajiv Chandrasekaran — Daily "Stand and Deliver" senate nities and sororities. First lady Barbara Bush was one of many celebrities attending this weekend's opening ceremonies for the Lucile Salter Packard Chil- slate, member ofthe candidates and several special fee MaeLee, a dren's Hospital. She took time out from a tour of the hospital to meet two patients, Joshua Evans, 9, and Shannon Brace, 4. -

Stuck! the Law and Economics of Residential Stagnation

DAVID SCHLEICHER Stuck! The Law and Economics of Residential Stagnation ABSTRACT. America has become a nation of homebodies. Rates of interstate mobility, by most estimates, have been falling for decades. Interstate mobility rates are particularly low and stagnant among disadvantaged groups -despite a growing connection between mobility and economic opportunity. Perhaps most importantly, mobility is declining in regions where it is needed most. Americans are not leaving places hit by economic crises, resulting in unemploy- ment rates and low wages that linger in these areas for decades. And people are not moving to rich regions where the highest wages are available. This Article advances two central claims. First, declining interstate mobility rates create problems for federal macroeconomic policymaking. Low rates of interstate mobility make it harder for the Federal Reserve to meet both sides of its "dual mandate": ensuring both stable prices and maximum employment. Low interstate mobility rates also impair the efficacy and affordability of federal safety net programs that rely on state and local participation, and reduce wealth and growth by inhibiting agglomeration economies. While determining an optimal rate of interstate mobility is difficult, policies that unnaturally inhibit interstate moves worsen na- tional economic problems. Second, the Article argues that governments, mostly at the state and local levels, have creat- ed a huge number of legal barriers to interstate mobility. Land-use laws and occupational licens- ing regimes limit entry into local and state labor markets. Different eligibility standards for pub- lic benefits, public employee pension policies, homeownership subsidies, state and local tax regimes, and even basic property law rules inhibit exit from low-opportunity states and cities. -

Economists Agree: We Need More COVID Relief Now

GOP Economists Agree: We Need More COVID Relief Now “Absolutely [in favor of the $1.9 trillion proposed American Rescue Plan]...The idea that you shouldn’t act right now is not consistent with the real time data…I would 100% support additional checks to people.” — Kevin Hassett, Former Economic Advisor to President Trump and former advisor to Sen. Romney “The $900 billion package that was passed a few weeks ago...all runs out by sometime in mid-March...That means hard-pressed Americans that are unemployed, have back rent, student loan payments, need food assistance, they’re going to need more help.” — Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics who has advised lawmakers on both sides of the aisle, including Sen. John McCain “One lesson from the financial crisis is that you want to be careful about doing too little.” — R. Glenn Hubbard, Former Economic Advisor to President George W. Bush and Sen. McCain “There are times to worry about the growing government debt. This is not one of them.” — Greg Mankiw, Former Economic Advisor to President George W. Bush and Sen. Mitt Romney “Additional fiscal support could be costly, but worth it if it helps avoid long-term economic damage and leaves us with a stronger recovery.” — Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell The Bottom Line: Now is the time for bold public investment to rescue the economy from the COVID economic crisis. Failure to do so could spell disaster for our communities, families, businesses, and economy.. -

United States Monetary and Economic Policy

UNITED STATES MONETARY AND ECONOMIC POLICY HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 30, 2003 Printed for the use of the Committee on Financial Services Serial No. 108–24 ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 87–237 PDF WASHINGTON : 2003 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 12:48 Aug 18, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\87237.TXT HBANK1 PsN: HBANK1 HOUSE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES MICHAEL G. OXLEY, Ohio, Chairman JAMES A. LEACH, Iowa BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts DOUG BEREUTER, Nebraska PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania RICHARD H. BAKER, Louisiana MAXINE WATERS, California SPENCER BACHUS, Alabama CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York MICHAEL N. CASTLE, Delaware LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois PETER T. KING, New York NYDIA M. VELA´ ZQUEZ, New York EDWARD R. ROYCE, California MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York ROBERT W. NEY, Ohio DARLENE HOOLEY, Oregon SUE W. KELLY, New York, Vice Chairman JULIA CARSON, Indiana RON PAUL, Texas BRAD SHERMAN, California PAUL E. GILLMOR, Ohio GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York JIM RYUN, Kansas BARBARA LEE, California STEVEN C. LATOURETTE, Ohio JAY INSLEE, Washington DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois DENNIS MOORE, Kansas WALTER B. JONES, JR., North Carolina CHARLES A. GONZALEZ, Texas DOUG OSE, California MICHAEL E. CAPUANO, Massachusetts JUDY BIGGERT, Illinois HAROLD E. -

Antitrust and Inequality: the Problem of Super-Firms

Florida State University College of Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Publications 2018 Antitrust and Inequality: The Problem of Super-Firms Shi-Ling Hsu Florida State University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/articles Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons Recommended Citation Shi-Ling Hsu, Antitrust and Inequality: The Problem of Super-Firms, 63 ANTITRUST BULL. 104 (2018), Available at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/articles/482 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hsu 105 election, income and wealth inequality have clearly become centrally important political issues. Even among Harvard Business School alumni, 63% believe that reducing inequality should be a “high” or “very high” priority.3 Concurrently, though less fervently, antitrust law has entered public discourse as a social ordering problem, as large, consolidated “super-firms”4 have grabbed ominously large market shares, limited consumer choices, and threatened to render local provi- sion of goods and services anachronistic. As disquiet grows over their ubiquity and their dis- placement of local institutions—and sometimes their treatment of customers—some have looked to antitrust laws to slow this trend. It is thus unsurprising that inequality and antitrust law should be joined from time to time. Unrest in these areas has brewed for decades, received heightened attention after the global financial crisis of 2008, and exploded into politics recently as populist anger. -

The Economic Outlook with Cea Chairman Kevin Hassett Hearing

S. HRG. 115–142 THE ECONOMIC OUTLOOK WITH CEA CHAIRMAN KEVIN HASSETT HEARING BEFORE THE JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 25, 2017 Printed for the use of the Joint Economic Committee ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 27–701 WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Sep 11 2014 11:59 Jan 30, 2018 Jkt 027189 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\27701.TXT SHAUN LAP51NQ082 with DISTILLER JOINT ECONOMIC COMMITTEE [Created pursuant to Sec. 5(a) of Public Law 304, 79th Congress] HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES SENATE PATRICK J. TIBERI, Ohio, Chairman MIKE LEE, Utah, Vice Chairman ERIK PAULSEN, Minnesota TOM COTTON, Arkansas DAVID SCHWEIKERT, Arizona BEN SASSE, Nebraska BARBARA COMSTOCK, Virginia ROB PORTMAN, Ohio DARIN LAHOOD, Illinois TED CRUZ, Texas FRANCIS ROONEY, Florida BILL CASSIDY, M.D., Louisiana CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York MARTIN HEINRICH, New Mexico, Ranking JOHN DELANEY, Maryland AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota ALMA S. ADAMS, PH.D., North Carolina GARY C. PETERS, Michigan DONALD S. BEYER, JR., Virginia MARGARET WOOD HASSAN, New Hampshire WHITNEY K. DAFFNER, Executive Director KIMBERLY S. CORBIN, Democratic Staff Director (II) VerDate Sep 11 2014 11:59 Jan 30, 2018 Jkt 027189 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 C:\DOCS\27701.TXT SHAUN LAP51NQ082 with DISTILLER C O N T E N T S OPENING STATEMENTS OF MEMBERS Hon. -

Goldman Sachs – “Beyond 2020: Post-Election Policies”

Note: The following is a redacted version of the original report published October 1, 2020 [27 pgs]. Global Macro ISSUE 93| October 1, 2020 | 7:20 PM EDT U Research $$$$ $$$$ TOPof BEYOND 2020: MIND POST-ELECTION POLICIES The US presidential election is shaping up to be one of the most contentious and consequential in modern history, making its potential policy, growth and market implications Top of Mind. We discuss the candidates’ economic policy priorities with Kevin Hassett, former Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Trump, and Jared Bernstein, economic advisor to former Vice President Biden. For perspectives on US foreign policy, we speak with Eurasia Group’s Ian Bremmer, who sees significant alignment between the candidates on many key foreign policy issues—including trade. We then assess the impacts of various election outcomes, concluding that a Democratic sweep could lead to higher inflation, an earlier Fed liftoff, and a positive change in the output gap, which we see as negative for the Dollar and credit markets, roughly neutral for US equities and oil, and positive for some EM assets. Finally, we turn to the actual race and ask Stanford law professor Nathaniel Persily a key question today: how and when would a contested election be resolved? WHAT’S INSIDE The president is very likely to pursue an infrastructure “package in a second term, and is probably prepared to INTERVIEWS WITH: recommend legislation amounting to up to $2tn of Kevin Hassett, former Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers in infrastructure -

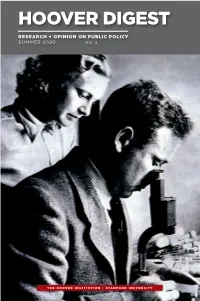

Hoover Digest

HOOVER DIGEST RESEARCH + OPINION ON PUBLIC POLICY SUMMER 2020 NO. 3 HOOVER DIGEST SUMMER 2020 NO. 3 | SUMMER 2020 DIGEST HOOVER THE PANDEMIC Recovery: The Long Road Back What’s Next for the Global Economy? Crossroads in US-China Relations A Stress Test for Democracy China Health Care The Economy Foreign Policy Iran Education Law and Justice Land Use and the Environment California Interviews » Amity Shlaes » Clint Eastwood Values History and Culture Hoover Archives THE HOOVER INSTITUTION • STANFORD UNIVERSITY The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace was established at Stanford University in 1919 by Herbert Hoover, a member of Stanford’s pioneer graduating class of 1895 and the thirty-first president of the United States. Created as a library and repository of documents, the Institution approaches its centennial with a dual identity: an active public policy research center and an internationally recognized library and archives. The Institution’s overarching goals are to: » Understand the causes and consequences of economic, political, and social change The Hoover Institution gratefully » Analyze the effects of government actions and public policies acknowledges gifts of support » Use reasoned argument and intellectual rigor to generate ideas that for the Hoover Digest from: nurture the formation of public policy and benefit society Bertha and John Garabedian Charitable Foundation Herbert Hoover’s 1959 statement to the Board of Trustees of Stanford University continues to guide and define the Institution’s mission in the u u u twenty-first century: This Institution supports the Constitution of the United States, The Hoover Institution is supported by donations from individuals, its Bill of Rights, and its method of representative government. -

Sidney D. Drell Professional Biography

Sidney D. Drell Professional Biography Present Position Professor Emeritus, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University (Deputy Director before retiring in 1998) Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution since 1998 Present Activities Member, JASON, The MITRE Corporation Member, Board of Governors, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel Professional and Honorary Societies American Physical Society (Fellow) - President, 1986 National Academy of Sciences American Academy of Arts and Sciences American Philosophical Society Academia Europaea Awards and Honors Prize Fellowship of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, November (1984-1989) Ernest Orlando Lawrence Memorial Award (1972) for research in Theoretical Physics (Atomic Energy Commission) University of Illinois Alumni Award for Distinguished Service in Engineering (1973); Alumni Achievement Award (1988) Guggenheim Fellowship, (1961-1962) and (1971-1972) Richtmyer Memorial Lecturer to the American Association of Physics Teachers, San Francisco, California (1978) Leo Szilard Award for Physics in the Public Interest (1980) presented by the American Physical Society Honorary Doctors Degrees: University of Illinois (1981); Tel Aviv University (2001), Weizmann Institute of Science (2001) 1983 Honoree of the Natural Resources Defense Council for work in arms control Lewis M. Terman Professor and Fellow, Stanford University (1979-1984) 1993 Hilliard Roderick Prize of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Science, Arms Control, and International Security 1994 Woodrow Wilson Award, Princeton University, for “Distinguished Achievement in the Nation's Service” 1994 Co-recipient of the 1989 “Ettore Majorana - Erice - Science for Peace Prize” 1995 John P. McGovern Science and Society Medalist of Sigma Xi 1996 Gian Carlo Wick Commemorative Medal Award, ICSC–World Laboratory 1997 Distinguished Associate Award of U.S. -

Sidney D. Drell 1926–2016

Sidney D. Drell 1926–2016 A Biographical Memoir by Robert Jaffe and Raymond Jeanloz ©2018 National Academy of Sciences. Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. SIDNEY daVID DRELL September 13, 1926–December 21, 2016 Elected to the NAS, 1969 Sidney David Drell, professor emeritus at Stanford Univer- sity and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, died shortly after his 90th birthday in Palo Alto, California. In a career spanning nearly 70 years, Sid—as he was universally known—achieved prominence as a theoretical physicist, public servant, and humanitarian. Sid contributed incisively to our understanding of the elec- tromagnetic properties of matter. He created the theory group at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) and led it through the most creative period in elementary particle physics. The Drell-Yan mechanism is the process through which many particles of the Standard Model, including the famous Higgs boson, were discovered. By Robert Jaffe and Raymond Jeanloz Sid advised Presidents and Cabinet Members on matters ranging from nuclear weapons to intelligence, speaking truth to power but with keen insight for offering politically effective advice. His special friendships with Wolfgang (Pief) Panofsky, Andrei Sakharov, and George Shultz highlighted his work at the interface between science and human affairs. He advocated widely for the intellectual freedom of scientists and in his later years campaigned tirelessly to rid the world of nuclear weapons. Early life1 and work Sid Drell was born on September 13, 1926 in Atlantic City, New Jersey, on a small street between Oriental Avenue and Boardwalk—“among the places on the Monopoly board,” as he was fond of saying. -

A Look at Upcoming Exhibits and Performances Page 34

Vol. XXXIV, Number 50 N September 13, 2013 Moonlight Run & Walk SPECIAL SECTION page 20 www.PaloAltoOnline.com A look at upcoming exhibits and performances page 34 Transitions 17 Spectrum 18 Eating 29 Shop Talk 30 Movies 31 Puzzles 74 NNews Council takes aim at solo drivers Page 3 NHome Perfectly passionate for pickling Page 40 NSports Stanford receiving corps is in good hands Page 78 2.5% Broker Fee on Duet Homes!* Live DREAM BIG! Big Home. Big Lifestyle. Big Value. Monroe Place offers Stunning New Homes in an established Palo Alto Neighborhood. 4 Bedroom Duet & Single Family Homes in Palo Alto Starting at $1,538,888 410 Cole Court <eZllb\lFhgkh^IeZ\^'\hf (at El Camino Real & Monroe Drive) Palo Alto, CA 94306 100&,,+&)01, Copyright ©2013 Classic Communities. In an effort to constantly improve our homes, Classic Communities reserves the right to change floor plans, specifications, prices and other information without prior notice or obliga- tion. Special wall and window treatments, custom-designed walks and patio treatments and other items featured in and around the model homes are decorator-selected and not included in the purchase price. Maps are artist’s conceptions and not to scale. Floor plans not to scale. All square footages are approximate. *The single family homes are a detached, single-family style but the ownership interest is condominium. Broker # 01197434. Open House | Sat. & Sun. | 1:30 – 4:30 27950 Roble Alto Drive, Los Altos Hills $4,250,000 Beds 5 | Baths 5.5 | Offices 2 | Garage 3 Car | Palo Alto Schools Home ~ 4,565 sq. -

Dr. Kevin Hassett Is One of the Nation's

KEVIN HASSETT Introduction DR. KEVIN HASSETT IS ONE OF THE NATION’S LEADING ECONOMISTS. A SENIOR FELLOW AND DIRECTOR OF ECONOMIC POLICY STUDIES AT THE RENOWNED AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE, KEVIN WAS FORMERLY A SENIOR ECONOMIST AT THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM AND AN ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ECONOMICS AND FINANCE AT THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY. WITH EXPERTISE IN ALL ASPECTS OF THE ECONOMY, KEVIN WAS THE CHIEF ECONOMIC ADVISOR TO SENATOR JOHN Leading Authorities, Inc. 1990 M Street, NW, Suite 800, Washington, DC 20036 1-800-SPEAKER | www.leadingauthorities.com MCCAIN DURING HIS 2000 PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN AND SENIOR ADVISOR TO HIS 2008 CAMPAIGN. KEVIN ALSO SERVED AS AN ADVISOR AND TELEVISION SURROGATE FOR PRESIDENT BUSH DURING THE 2004 CAMPAIGN. HE ALSO WAS A POLICY CONSULTANT TO THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY DURING BOTH THE BUSH AND CLINTON ADMINISTRATIONS AND HE PROVIDES ADVICE REGULARLY TO NUMEROUS FORTUNE 500 COMPANIES. IN ADDITION TO BEING A DISTINGUISHED ECONOMIST, KEVIN ALSO WRITES A WEEKLY COLUMN FOR Leading Authorities, Inc. 1990 M Street, NW, Suite 800, Washington, DC 20036 1-800-SPEAKER | www.leadingauthorities.com BLOOMBERG AND BUSINESS WEEK THAT IS SYNDICATED IN NEWSPAPERS NATIONWIDE. HE IS ALSO A COLUMNIST FOR NATIONAL REVIEW, AND REGULARLY PLACES ARTICLES IN TOP NATIONAL PUBLICATIONS SUCH AS TIME, THE ATLANTIC MONTHLY, USA TODAY, AND THE WALL STREET JOURNAL. KEVIN’S COMMENTARIES ARE ALSO AIRED REGULARLY BY NUMEROUS TELEVISION OUTLETS, INCLUDING RECENT APPEARANCES ON CNN, CNBC, ABC EVENING NEWS, AND PBS’S MARKETPLACE RADIO. LADIES AND GENTLEMAN, PLEASE WELCOME KEVIN HASSETT.