The Changing Retail Payments Landscape: What Role for Central Banks?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

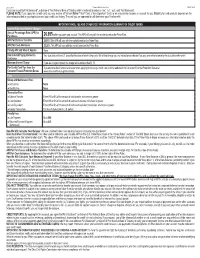

Scotiabank®* Gold American Express® Card Application Disclosure

File Name: DM-AQ_Disclosure_CSAGDS-E_0716 Trim: 8.5” x 11” Creative & Production Services Bleed: 0" Safety: n/a Mech Res: 300dpi 100 Yonge Street, 10th Floor Toronto, ON M5C 2W1 Colours: CMYK Scotiabank®* Gold American Express® Card CSAGDS-E (08/16) Application Disclosure Statement Annual Annual interest rates are in effect on the day the account is opened (whether or not a card is activated). Interest Purchases: 19.99% Rate or Rates Cash advances**, balance transfers and Scotia®* Credit Card Cheques: 22.99% Your preferred annual interest rates will increase to standard rates of 24.99% on purchases and 27.99% on cash advances, balance transfers and Scotia Credit Card Cheques if you do not make your minimum payment by the payment due date 2 or more times in any 12 month period. This will take effect in the third statement period following the missed payment that caused the rates to increase. These rates will remain in effect until you make your minimum payments by the payment due date for 12 consecutive months. Interest-free 21 days Grace Period You will benefit from an interest-free grace period of at least 21 days for new purchases± if you pay off your balance on your monthly statement in full by the payment due date. This grace period will be automatically extended to at least 25 days on your next monthly statement whenever you do not pay your balance in full by the payment due date. Upon paying your balance in full by the payment due date, this grace period will revert back to at least 21 days on your next monthly statement. -

Collaborate, Understand, Innovate

Collaborate, understand, innovate. 2013 Reports and Accounts his report describes the work that the UniCredit & Universities Foundation is doing to support the studies and research of TEurope’s brightest young minds. It details the full range of programs implemented by the foundation to assist promising young people develop original ideas in the fields of economics and finance. Collaboration, understanding, innovation, facilitation, selectivity and responsiveness are all key aspects of the UniCredit & Universities mission. These words express the motivations that underlie the foundation’s programs for students and researchers who want to make a difference. The foundation is committed to providing them with concrete solutions and tangible benefits that can clear a pathway to their future careers. At the heart of its activities, UniCredit & Universities listens closely to its scholars and fellows to ensure that it can provide them with direct and effective support. This is a vital part of the process of enabling them to focus on their work at the world’s best academic institutions. The foundation seeks to make these opportunities available to students and researchers in every community where UniCredit is present. Inside this report, you will find the full record of the activities and ideals embraced by UniCredit & Universities. The stories and statistics it contains are intended to further enhance foundation’s relationship with all of its stakeholders and reaffirm its commitment to its work. 2013 Reports and Accounts Collaborate Working more efficiently, with better results Effective academic work requires a willingness and an ability to interact well with everyone in the university environment. At UniCredit & Universities, collaboration is not only a way of working but also a mindset. -

Consumer Credit Card Agreement and Disclosure

CONSUMER CREDIT CARD AGREEMENT AND DISCLOSURE MASTERCARD This Consumer Credit Card Agreement and Disclosure together with the Account Opening Disclosure and any other Account opening documents or any subsequent documents provided to You related to this Account (hereinafter collectively referred to as “Agreement”) govern the terms and conditions of this Account. “We,” “Us,” “Our” and “Ours” and “Credit Union” refers to Pen Air Federal Credit Union with which this Agreement is made. “You,” “Your,” and “Yours” refers to each applicant and co-applicant for the Account; any person responsible for paying the Account; and anyone You authorize to use, access or service the Account. "Card" means the Mastercard® credit card and any other access devices, duplicates, renewals, or substitutions, the Credit Union issues to You. "Account" means the line of credit established by this Agreement and includes Your Card. SECURITY INTEREST You grant the Credit Union a security interest under the Uniform Commercial Code and under any common law rights the Credit Union may have in any goods You purchase. If You give the Credit Union a specific pledge of shares by signing a separate pledge of shares, Your pledged shares will secure Your Account. You may not withdraw amounts that have been specifically pledged to secure Your Account until the Credit Union agrees to release all or part of the pledged amount. You grant Us a security interest in all individual and joint share and/or deposit accounts You have with Us now and in the future to secure Your credit card Account. Shares and deposits in an IRA or any other account that would lose special tax treatment under state or federal law if given as security are not subject to the security interest You have given in Your shares and deposits. -

Summary of Credit Terms- Union Bank® Cashback Rewards Visa® Card

Summary of Credit Terms- Union Bank® Cashback Rewards Visa® Card PLEASE NOTE: If you apply for the Union Bank Cashback Rewards Visa Card and meet our eligibility criteria for the Visa Signature® Card, you agree that we may consider your application as one for (and upgrade you to) the Union Bank Cashback Rewards Visa Signature Card. Interest Rates and Interest Charges Annual Percentage Rate Introductory APR for the first 12 months that your account is open. (APR) for Purchases 0.00% After that, your APR will be 13.99% to 23.99%, based on your creditworthiness. This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. APR for Balance Transfers 0.00% Introductory APR for the first 12 months that your account is open. After that, your APR will be 13.99% to 23.99%, based on your creditworthiness. This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. APR for Cash Advances 25.25%. This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. Penalty APR None Paying Interest Your due date is at least 21 calendar days after the close of each billing cycle. We will not charge you any interest on purchases if you pay your entire balance by the due date each month. We will begin charging interest on cash advances and balance transfers on the transaction date. Minimum Interest Charge If you are charged interest, the charge will be no less than $1.75. For Credit Card Tips from To learn more about factors to consider when applying for or using a credit card, visit the the Consumer Financial website of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau at Protection Bureau http://www.consumerfinance.gov/learnmore. -

Authorisation Service Sales Sheet Download

Authorisation Service OmniPay is First Data’s™ cost effective, Supported business profiles industry-leading payment processing platform. In addition to card present POS processing, the OmniPay platform Authorisation Service also supports these transaction The OmniPay platform Authorisation Service gives you types and products: 24/7 secure authorisation switching for both domestic and international merchants on behalf of merchant acquirers. • Card Present EMV offline PIN • Card Present EMV online PIN Card brand support • Card Not Present – MOTO The Authorisation Service supports a wide range of payment products including: • Dynamic Currency Conversion • Visa • eCommerce • Mastercard • Secure eCommerce –MasterCard SecureCode, Verified by Visa and SecurePlus • Maestro • Purchase with Cashback • Union Pay • SecureCode for telephone orders • JCB • MasterCard Gaming (Payment of winnings) • Diners Card International • Address Verification Service • Discover • Recurring and Installment • BCMC • Hotel Gratuity • Unattended Petrol • Aggregator • Maestro Advanced Registration Program (MARP) Supported authorisation message protocols • OmniPay ISO8583 • APACS 70 Authorisation Service Connectivity to the Card Schemes OmniPay Authorisation Server Resilience Visa – Each Data Centre has either two or four Visa EAS servers and resilient connectivity to Visa Europe, Visa US, Visa Canada, Visa CEMEA and Visa AP. Mastercard – Each Data Centre has a dedicated Mastercard MIP and resilient connectivity to the Mastercard MIP in the other Data Centre. The OmniPay platform has connections to Banknet for both European and non-European authorisations. Diners/Discover – Each Data Centre has connectivity to Diners Club International which is also used to process Discover Card authorisations. JCB – Each Data Centre has connectivity to Japan Credit Bureau which is used to process JCB authorisations. UnionPay – Each Data Centre has connectivity to UnionPay International which is used to process UnionPay authorisations. -

Benefits of Open Payment Systems and the Role of Interchange

Benefits of Open Payment Systems and the Role of Interchange U.S. Version Delivering value through payment alternatives At MasterCard Worldwide, we take great pride in the many ways we advance com- merce. From the millions of consumers and businesses around the world who rely on our cards on a daily basis, to the retailers who accept them and institutions that issue them, it’s clear that the products and services we offer deliver extraordinary value. With demand for fast, convenient and safe payment alternatives rapidly accelerating, commerce is increasingly driven by blips on a screen, numbers punched on a keyboard, cards swiped through electronic readers and chip-activated cell phones. In fact, our products and services are so ingrained in everyday life that the value we deliver is all too often taken for granted. Perhaps the easiest way to grasp the true value of electronic payments is to envision a world without them. Clearly, if electronic payments came to a sudden halt, many facets of commerce—travel, trade and the Internet just to name a few—would face dire consequences. While cash and checks still have their place, they lack the speed, convenience and safety required by consumers, businesses and governments in today’s fast-paced, ever-shrinking world. To be sure, the widespread use of electronic payments and the sophisticated networks that seamlessly link millions of consumers, merchants and financial institutions around the globe are at the heart of commerce. Their importance is clear not only in industrialized nations, but in emerging markets as well, where we are making inroads in building a bridge to the modern economy. -

Visa's Annual Report

Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 2017 Mission Statement To connect the world through the most innovative, reliable and secure digital payment network that enables individuals, businesses and economies to thrive. Financial Highlights (GAAP) In millions (except for per share data) FY 2015 FY 2016 FY 2017 Operating revenues $13,880 $15,082 $18,358 Operating expenses $4,816 $7,199 $6,214 Operating income $9,064 $7, 883 $12,144 Net income $6,328 $5,991 $6,699 Stockholders' equity $29,842 $32,912 $32,760 Diluted class A common stock earnings per share $2.58 $2.48 $2.80 Financial Highlights (ADJUSTED)1 In millions (except for per share data) FY 2015 FY 2016 FY 2017 Operating revenues $13,880 $15,082 $18,358 Operating expenses $4,816 $5,060 $6,022 Operating income $9,064 $10,022 $12,336 Net income $6,438 $6,862 $8,335 Diluted class A common stock earnings per share $2.62 $2.84 $3.48 Operational Highlights² 12 months ended September 30 (except where noted) 2015 2016 2017 Total volume, including payments and cash volume³ $7.4 trillion $8.2 trillion $10.2 trillion Payments volume³ $4.9 trillion $5.8 trillion $7.3 trillion Transactions processed on Visa's networks 71.0 billion 83.2 billion 111.2 billion Cards⁴ 2.4 billion 2.5 billion 3.2 billion Stock Performance The accompanying graph and chart compares the cumulative total return on $350 Visa’s common stock with the cumulative total return on Standard & Poor’s 500 Index and the Standard & Poor’s 500 Data Processing Index from September 30, $300 2012 through September 30, 2016. -

Credit Card Disclosure (PDF)

OPEN-END CONSUMER CREDIT AGREEMENTS AND TRUTH IN LENDING DISCLOSURES Effective July 1, 2016 FEDERALLY INSURED BY NCUA PATELCO CREDIT UNION in agreements governing specific services you have and your general OPEN-END CONSUMER CREDIT AGREEMENTS AND membership agreements with Patelco, and you must have a satisfactory TRUTH IN LENDING DISCLOSURES loan, account and membership history with Patelco. MASTERCARD® CREDIT CARDS 2. On joint accounts, each borrower can borrow up to the full amount of SECURED MASTERCARD CREDIT CARD the credit limit without the other’s consent. PERSONAL LINE OF CREDIT 3. Advances Effective: JULY 1, 2016 a. Credit Card Advances: Credit Cards will be issued as instructed on This booklet contains agreements and Truth in Lending Disclosures your application. To make a purchase or get a cash advance, you that govern your use of the following Patelco Credit Union open-end can present the Card to a participating MasterCard plan merchant, consumer credit programs: to the Credit Union, or to another financial institution, and sign Pure MasterCard Payback Rewards World MasterCard the sales or cash advance draft imprinted with your Card number. Keep sales and cash advance drafts to reconcile your monthly Pure Secured MasterCard Passage Rewards World Elite MasterCard statements. You can also make purchases by giving your Card Points Rewards World MasterCard Personal Line of Credit number to a merchant by telephone, over the internet, or by other means, in which case your only record of the transaction may In addition to this booklet, -

Pricing Schedule

PRICING SCHEDULE This is an example of terms that were available to recent applicants as of 12/31/18. They may not be available now. If you apply, your terms will be based on the terms of the offer when you apply. This Pricing Schedule is part of the Cardmember Agreement. Interest Rates and Interest Charges Annual Percentage Rate (APR) for Purchases 24.99%. This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate.1 APR for Balance Transfers 24.99%. This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate.1 APR for Cash Advances 26.99%. This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate.1 Penalty APR and When It Applies None Your due date is at least 25 days after the close of each billing period (at least 23 days for billing periods that begin in February). We will not charge you any interest on purchases if you pay your entire balance by the due date each month. We will begin charging interest on Paying Interest cash advances and balance transfers as of the later of the transaction date or the first day of the billing period in which the transaction posted to your Account. Minimum Interest Charge If you are charged interest, the charge will be no less than $0.50. Fees Annual Fee None Balance Transfer Fee 3% of the amount of each transfer. Cash Advance Fee Either $10 or 5% of the amount of each cash advance, whichever is greater. Late Fee None the first time you pay late. -

How to Find the Best Credit Card for You

How to find the best credit card for you Why should you shop around? Comparing offers before applying for a credit card helps you find the right card for your needs, and helps make sure you’re not paying higher fees or interest rates than you have to. Consider two credit cards: One carries an 18 percent interest rate, the other 15 percent. If you owed $3,000 on each and could only afford to pay $100 per month, it would cost more and take longer 1. Decide how you plan to pay off the higher-rate card. to use the card The table below shows examples of what it might You may plan to pay off your take to pay off a $3,000 credit card balance, paying balance every month to avoid $100 per month, at two different interest rates. interest charges. But the reality is, many credit card holders don’t. If you already have a credit card, let APR Interest Months history be your guide. If you have carried balances in the past, or think 18% = $1,015 41 you are likely to do so, consider 15% = $783 38 credit cards that have the lowest interest rates. These cards typically do not offer rewards and do not The higher-rate card would cost you an extra charge an annual fee. $232. If you pay only the minimum payment every month, it would cost you even more. If you have consistently paid off your balance every month, then you So, not shopping around could be more expensive may want to focus more on fees and than you think. -

Pricing Schedule This Is an Example of Terms That Were Available to Recent Applicants As of 3/30/12

PriciNG SCHEDULE This is an example of terms that were available to recent applicants as of 3/30/12. They may not be available now. If you apply, your terms will be based on the terms of the offer when you apply. This Pricing Schedule is part of the Cardmember Agreement. Interest Rates and Interest Charges Annual Percentage Rate From 9.99% to 22.99%. This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate.1 (APR) for Purchases APR for Balance Transfers From 9.99% to 22.99%. This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate.1 APR for Cash Advances 23.99%. This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate.1 Penalty APR and From up to 14.99% to up to 27.99% based on your creditworthiness and other factors. When It Applies This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate.2 This APR may be applied to new purchases and balance transfers if you make a late payment. How Long Will the Penalty APR Apply? If your APRs for new purchases and balance transfers are increased for a late payment, the Penalty APR will apply indefinitely. Paying Interest Your due date is at least 25 days after the close of each billing period (at least 23 days for billing periods that begin in February). We will not charge you any interest on purchases if you pay your entire balance by the due date each month. We will begin charging interest on cash advances and balance transfers as of the later of the transaction date or the first day of the billing period in which the transaction posted to your Account. -

How We Will Calculate Your Balance:We Use a Method Called “Average Daily Balance (Including New Purchases)”. Index and When

232 - 121144 Platinum Edition® Visa® Card T-GULF-2005 Cards are issued by First Bankcard®, a division of First National Bank of Omaha, which is referred to below as “we”, “us”, “our”, and “First Bankcard”. PLEASE NOTE: If you apply for a credit card, you may receive a Platinum Edition® Visa® Card, a Visa Signature® Card, or we may decline to open an account for you. Eligibility for card products depends on the information provided in your application and your credit card history. The card you are approved for will determine your Visa benefits. IMPORTANT RATE, FEE AND OTHER COST INFORMATION (SUMMARY OF CREDIT TERMS) Interest Rates and Interest Charges Annual Percentage Rate (APR) for Purchases 26.99% when you open your account. This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. APR for Balance Transfers 26.99% This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. APR for Cash Advances 25.24%. This APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. Penalty APR and When it Applies None How to Avoid Paying Interest on Your due date is at least 21 days after the close of each billing cycle. We will not charge you any interest on purchases if you pay your entire balance by the due date each month.1 Purchases Minimum Interest Charge If you are charged interest, the charge will be no less than $1.75. For Credit Card Tips from the To learn more about factors to consider when applying for or using a credit card, visit the website of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau at Consumer Financial Protection Bureau www.consumerfinance.gov/learnmore.