How De Gasperi Sent Guareschi to Prison Alan R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gerusalemme!Gerusalemme! Dominique Lapierre/ Larry Collins 1575 Attualità Se Wada, Se Wada, Fada Mario Vatta 1576 169 Autobiografia Ricordo Di Una Vita Paul Mccartney

N° GENERE TITOLO AUTORE attualità Generazioni perdute Alvaro Costantini 1566 attualità Gerusalemme!Gerusalemme! Dominique LaPierre/ Larry Collins 1575 attualità Se wada, se wada, fada Mario Vatta 1576 169 autobiografia Ricordo di una vita Paul McCartney 324 autobiografia Il cancello Francois Bizot 644 autobiografia Non ci vuole un eroe Gen. N. Schwarzkopf 734 autobiografia Chi sogna nuovi gerani Giovannino Guareschi 100 avventura La legge del deserto Wilbur Smith 163 avventura Quando sognavo Cuba Alberto Mattei 232 avventura Un'aquila nel cielo Wilbur Smith 233 avventura La legge del deserto Wilbur Smith 243 avventura Atlantide Clive Cussler 302 avventura Destinazione inferno Lee Child 303 avventura L'ultima fortezza Bernard Cornwell 309 avventura Aquile grigie Duane Unkefer 399 avventura Dove finisce l'arcobaleno Wilbur Smith 400 avventura L'uccello del sole Wilbur Smith 409 avventura Gli eredi Wilbur Smith 410 avventura Ci rivedremo all'inferno Wilbur Smith 412 avventura Il cacciatore Clive Cussler 424 avventura L'ultima preda Wilbur Smith 428 avventura Cyclops Clive Cussler 440 avventura La montagna dei diamanti Wilbur Smith 441 avventura L'alba sulle ali Mary Alice Monroe 445 avventura La notte del leopardo Wilbur Smith 469 avventura Monsone Wilbur Smith 470 avventura Il destino del leone Wilbur Smith 542 avventura Terreno fatale Dale Brown 590 avventura L'oro di Sparta Clive Cussler 621 avventura Senza rimorso Tom Clancy 707 avventura Atlantide Clive cussler 719 avventura Classe Kilo Patrick Robinson 783 avventura Nati per combattere -

Italy's Atlanticism Between Foreign and Internal

UNISCI Discussion Papers, Nº 25 (January / Enero 2011) ISSN 1696-2206 ITALY’S ATLANTICISM BETWEEN FOREIGN AND INTERNAL POLITICS Massimo de Leonardis 1 Catholic University of the Sacred Heart Abstract: In spite of being a defeated country in the Second World War, Italy was a founding member of the Atlantic Alliance, because the USA highly valued her strategic importance and wished to assure her political stability. After 1955, Italy tried to advocate the Alliance’s role in the Near East and in Mediterranean Africa. The Suez crisis offered Italy the opportunity to forge closer ties with Washington at the same time appearing progressive and friendly to the Arabs in the Mediterranean, where she tried to be a protagonist vis a vis the so called neo- Atlanticism. This link with Washington was also instrumental to neutralize General De Gaulle’s ambitions of an Anglo-French-American directorate. The main issues of Italy’s Atlantic policy in the first years of “centre-left” coalitions, between 1962 and 1968, were the removal of the Jupiter missiles from Italy as a result of the Cuban missile crisis, French policy towards NATO and the EEC, Multilateral [nuclear] Force [MLF] and the revision of the Alliance’ strategy from “massive retaliation” to “flexible response”. On all these issues the Italian government was consonant with the United States. After the period of the late Sixties and Seventies when political instability, terrorism and high inflation undermined the Italian role in international relations, the decision in 1979 to accept the Euromissiles was a landmark in the history of Italian participation to NATO. -

Are Gestures Worth a Thousand Words? an Analysis of Interviews in the Political Domain

Are Gestures Worth a Thousand Words? An Analysis of Interviews in the Political Domain Daniela Trotta Sara Tonelli Universita` degli Studi di Salerno Fondazione Bruno Kessler Via Giovanni Paolo II 132, Via Sommarive 18 Fisciano, Italy Trento, Italy [email protected] [email protected] Abstract may provide important information or significance to the accompanying speech and add clarity to the Speaker gestures are semantically co- expressive with speech and serve different children’s narrative (Colletta et al., 2015); they can pragmatic functions to accompany oral modal- be employed to facilitate lexical retrieval and re- ity. Therefore, gestures are an inseparable tain a turn in conversations stam2008gesture and part of the language system: they may add assist in verbalizing semantic content (Hostetter clarity to discourse, can be employed to et al., 2007). From this point of view, gestures fa- facilitate lexical retrieval and retain a turn in cilitate speakers in coming up with the words they conversations, assist in verbalizing semantic intend to say by sustaining the activation of a tar- content and facilitate speakers in coming up with the words they intend to say. This aspect get word’s semantic feature, long enough for the is particularly relevant in political discourse, process of word production to take place (Morsella where speakers try to apply communication and Krauss, 2004). strategies that are both clear and persuasive Gestures can also convey semantic meanings. using verbal and non-verbal cues. For example,M uller¨ et al.(2013) discuss the prin- In this paper we investigate the co-speech ges- ciples of meaning creation and the simultaneous tures of several Italian politicians during face- and linear structures of gesture forms. -

Don Camillo and His Flock

Don Camillo and His Flock Mondo piccolo "Don Camillo e il suo Gregge" by Giovanni Guareschi, 1908-1968 Translated by Frances Frenaye Published: 1961 J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents The Little World The Thirteenth-Century Angel The Dance of the Hours Rhadames The Stuff from America A Matter of Conscience War to the Knife The Polar Pact The Petition A Solomon Come to Judgment Thunder on the Right Red Letter Day The Strike Thunder The Wall The Sun Also Rises Technique of the Coup d‘État Benefit of Clergy Out of the Night The Bicycle The Prodigal Son Shotgun Wedding Seeds of Hate War of Secession Bianco The Ugly Madonna The Flying Squad Horses of a Different Color Blue Sunday Don Camillo Gets in Trouble When the Rains Came The Right Bell Everyone at his Post Appointment at Midnight J J J J J I I I I I The Little World When I was a young man I worked as a reporter and went around all day on a bicycle looking for news stories for the paper. One day I met a girl and after that I spent so many hours thinking about how this girl would feel if I became Emperor of Mexico, or maybe died instead, that I had very little time left for anything else. So at night I filled my allotted space with invented stories which people liked very much because they were much more true to life than true ones. Of course, there is nothing surprising about this, because stories, like people, grow in a certain atmosphere. -

Politica E Istituzioni Negli Scritti Di Antonio Segni

Politica e istituzioni negli scritti di Antonio Segni Questa antologia di scritti politici vuol essere un con- tributo alla ricostruzione della biografia intellettuale e politica di Antonio Segni. L’interpretazione sull’opera di Segni ancora oggi prevalente – anche se, in seguito a recenti studi, comincia a mostrare le sue debolezze – è condizionata dalla decennale polemica politica sui fatti dell’estate del 19641. Si tratta di un’interpretazio- 1 Tra gli studi più recenti dedicati a Segni mi permetto di rinviare a S. Mura, Le esperienze istituzionali di Antonio Segni negli anni del Diario, in A. Segni, Diario (1956-1964), a cura di S. Mura, Bologna, il Mulino, 2012, pp. 21-97. Per un completo profilo biografico, A. Giovagnoli, Antonio Segni, in Il Parlamento Italiano. 1861-1988. Il centro-sinistra. La “stagione” di Moro e Nenni. 1964-1968, vol. XIX, Milano, Nuova Cei, 1992, pp. 244-268. Su Segni professore universitario e giurista, soprattutto: A. Mattone, Segni Antonio, in Dizionario biografico dei giuristi italiani (XII-XX secolo), diretto da I. Birocchi, E. Cortese, A. Mattone, M. N. Miletti, a cura di M. L. Carlino, G. De Giudici, E. Fab- bricatore, E. Mura, M. Sammarco, vol. II, Bologna, il Mulino, 2013, pp. 1843-1845; G. Fois, Storia dell’Università di Sassari 1859-1943, Roma, Carocci, 2000; A. Mattone, Gli studi giuridici e l’insegnamento del diritto (XVII-XX secolo), in Idem (a cura di), Storia dell’Università di Sassari, vol. I, Nuoro, Ilisso, 2010, pp. 221-230; F. Cipriani, Storie di processualisti e di oligarchi. La procedura civile nel Regno d’Italia (1866-1936), Milano, Giuffrè, 1991. -

Sergio Mattarella

__________ Marzo 2021 Indice cronologico dei comunicati stampa SEZIONE I – DIMISSIONI DI CORTESIA ......................................................................... 9 Presidenza Einaudi...........................................................................................................................9 Presidenza Gronchi ..........................................................................................................................9 Presidenza Segni ..............................................................................................................................9 Presidenza Saragat.........................................................................................................................10 Presidenza Leone ...........................................................................................................................10 Presidenza Pertini ..........................................................................................................................10 Presidenza Cossiga ........................................................................................................................11 Presidenza Ciampi .........................................................................................................................11 Presidenza Mattarella ....................................................................................................................11 SEZIONE II – DIMISSIONI EFFETTIVE ........................................................................ -

Elenco Dei Governi Italiani

Elenco dei Governi Italiani Questo è un elenco dei Governi Italiani e dei relativi Presidenti del Consiglio dei Ministri. Le Istituzioni in Italia Le istituzioni della Repubblica Italiana Costituzione Parlamento o Camera dei deputati o Senato della Repubblica o Legislature Presidente della Repubblica Governo (categoria) o Consiglio dei Ministri o Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri o Governi Magistratura Consiglio Superiore della Magistratura (CSM) Consiglio di Stato Corte dei Conti Governo locale (Suddivisioni) o Regioni o Province o Comuni Corte costituzionale Unione Europea Relazioni internazionali Partiti e politici Leggi e Regolamenti parlamentari Elezioni e Calendario Referendum modifica Categorie: Politica, Diritto e Stato Portale Italia Portale Politica Indice [nascondi] 1 Regno d'Italia 2 Repubblica Italiana 3 Sigle e abbreviazioni 4 Politici con maggior numero di Governi della Repubblica Italiana 5 Voci correlate Regno d'Italia Periodo Nome del Governo Primo Ministro 23 marzo 1861 - 12 giugno 1861 Governo Cavour Camillo Benso Conte di Cavour[1] 12 giugno 1861 - 3 marzo 1862 Governo Ricasoli I Bettino Ricasoli 3 marzo 1862 - 8 dicembre 1862 Governo Rattazzi I Urbano Rattazzi 8 dicembre 1862 - 24 marzo 1863 Governo Farini Luigi Carlo Farini 24 marzo 1863 - 28 settembre 1864 Governo Minghetti I Marco Minghetti 28 settembre 1864 - 31 dicembre Governo La Marmora Alfonso La Marmora 1865 I Governo La Marmora 31 dicembre 1865 - 20 giugno 1866 Alfonso La Marmora II 20 giugno 1866 - 10 aprile 1867 Governo Ricasoli -

'Special Rights and a Charter of the Rights of the Citizens of the European Community' and Related Documents

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT Proceedings of the Round Table on 'Special rights and a charter of the rights of the citizens of the European Community' and related documents (Florence, 26 to 28 October 1978) Selected Documents Foreword by Emilio Colombo President of the European Parliament Introduction by John P. S. Taylor Director-General Secretariat Directorate-General for Research and Documentation September 1979 EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT PROCEEDINGS of the Round Table on Special rights and a charter of the rights of the citizens of the European Community and related documents Florence 26 to 28 October 1978 COMPILED BY THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT'S DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR RESEARCH AND DOCUMENTATION This publications is also available in the following languages: DA ISBN 92-823-0007-2 DE ISBN 92-823-0008-0 FR ISBN 92-823-0010-2 IT ISBN 92-823-0011-0 NL ISBN 92-823-0012-9 Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this volume ©Copyright European Parliament, Luxembourg, 1979 Printed in the FJ.!. of Germany Reproduction authorized, in whole or in part, provided the source is acknowledged ISBN 92-823-0009-9 Catalogue number: AX-28-79-423-EN-C CONTENTS Page Foreword by Mr Emilio Colombo, President of the European Parliament 5 Introduction by Mr J.P. S. Taylor, the European Parliament's Director-General of Research and Documentation 7 Round Table programme 9 List of participants 11 Summary report of the discussions 15 Report by Mr Scelba, chairman of the Round Table 53 Report by Mr Bayerl, rapporteur for the European Parliament's Legal Affairs Committee . 69 Report by Mr Scelba to the Bureau of the European Parliament on the progress of the Round Table . -

Aldo Moro E L'apertura a Sinistra: Dalla Crisi Del Centrismo Al Centro-Sinistra

1 Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche Cattedra di Teoria e Storia dei Partiti e dei Movimenti Politici ALDO MORO E L’APERTURA A SINISTRA: DALLA CRISI DEL CENTRISMO AL CENTRO-SINISTRA ORGANICO RELATORE CANDIDATO Prof. Andrea Ungari Mirko Tursi Matr. 079232 ANNO ACCADEMICO 2017/18 2 3 INDICE INTRODUZIONE 4 CAPITOLO PRIMO LA CRISI DEL CENTRISMO E L’ASCESA DI MORO NEL PANORAMA POLITICO ITALIANO (1953-1959) 6 1.1 La presidenza del gruppo parlamentare della Dc e la prima apertura ai socialisti 6 1.2 L’elezione di Gronchi alla presidenza della RepubbliCa e la marCia di avvicinamento tra Dc e Psi 9 1.3 Le elezioni politiche del 1958 e l’elezione di Moro a segretario della DC 11 1.4 Il Congresso di Firenze e l’autonomia del partito dalle gerarchie ecclesiastiche 16 CAPITOLO SECONDO LA NASCITA DEL PRIMO GOVERNO DI CENTRO-SINISTRA ORGANICO (1960-1963) 23 2.1 L’ultimo governo di centro-destra e il passaggio al governo delle “convergenze parallele” 23 2.2 Le prime giunte di centro-sinistra e la difficile preparazione all’incontro ideologico tra cattolici e soCialisti 31 2.3 Il Congresso di Napoli ed il programma riformatore del quarto governo Fanfani 35 2.4 Le elezioni politiche del 1963 e la nascita del primo governo di centro-sinistra organico guidato da Moro 44 CAPITOLO TERZO IL DECLINO DELLA FORMULA DI CENTRO-SINISTRA (1964-1968) 53 3.1 La crisi politica del 1964 ed il tormentato avvio del II Governo Moro 53 3.2 L’elezione di Saragat alla presidenza della Repubblica e l’irreversibilità della formula di centro-sinistra 63 3.3 Il III Governo Moro e l’unificazione socialista 70 3.4 La tornata elettorale del 1968: fine dell’esperienza di centro-sinistra 76 CONCLUSIONE 83 ABSTRACT 86 BIBLIOGRAFIA 87 4 INTRODUZIONE Il periodo storiCo Che si estende dal 1953 al 1968 rappresenta un unicum all’interno della politiCa italiana e CostituisCe uno dei temi più affasCinanti della storia della Prima RepubbliCa. -

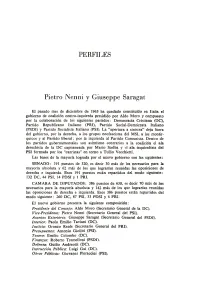

PERFIJ.,ES Pietro N Enni Y Giuseppe Saragat

PERFIJ.,ES Pietro N enni y Giuseppe Saragat El pasado mes de diciembre de 1963 ha quedado constituído en Italia el gobierno de coalición centro-izquierda presidido por Aldo Moro y compuesto por la colaboración de los siguientes partidos: Democracia Cristiana (DC), Partido Republicano Italiano (PRI), Partido Social-Demócrata Italiano (PSDI) y Partido Socialista Italiano (PSI). La "apertura a sinistra" deja fuera del gobierno, por la derecha, a los grupos neofascistas del MSI, a los monár quicos y al Partido liberal; por la izquierda al Partido Comunista. Dentro de los partidos gubernamentales son asimismo contrarios a la coalición el ala derechista de la DC capitaneada por Mario Scelba y el ala izquierdista del PSI formada por los "carristas" en tomo a Tullio Vecchietti. Las bases de la mayoría lograda por el nuevo gobierno son las siguientes: SENADO: 191 puestos de 320, es decir 30 más de los necesarios para la mayoría absoluta y 62 más de los que lograrían reunidas las oposiciones de derecha e izquierda. Esos 191 puestos están repartidos del modo siguiente: 132 DC, 44 PSI, 14 PDSI y 1 PRI. CAMARA DE DIPUTADOS: 386 puestos de 630, es decir 70 más de los necesarios para la mayoría absoluta y 142 más de los que lograrían reunidas las oposiciones de derecha e izquierda. Esos 386 puestos están repartidos del modo siguiente: 260 DC, 87 PSI, 33 PDSI y 6 PRI. El nuevo gobierno presenta la siguiente composición: Presidente del Consejo: Aldo Moro (Secretario General de la DC). Vice-Presidente: Pietro Nenni (Secretario General del PSI). Asuntos Exteriores: Giuseppe Saragat (Secretario General del PSDI). -

The Italian Communist Party and The

CENTRAL EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY The Italian Communist Party and the Hungarian crisis of 1956 History one-year M. A. In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Candidate: Aniello Verde Supervisor: Prof. Marsha Siefert Second reader: Prof. Alfred Rieber CEU eTD Collection June 4th, 2012 A. Y. 2011/2012 Budapest, Hungary Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection Acknowledgements I would like to express my frank gratitude to professors Marsha Siefert and Alfred Rieber for their indispensible support, guidance and corrections. Additionally, I would like to thank my Department staff. Particularly, I would like to thank Anikó Molnar for her continuous help and suggestions. CEU eTD Collection III ABSTRACT Despite a vast research about the impact of the Hungarian crisis of 1956 on the legacy of Communism in Italy, the controversial choices of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) have been often considered to be a sort of negative exception in the progressive path of Italian Communism toward modern European socialism. Instead, the main idea of this research is to reconstruct the PCI’s decision-making within the context of the enduring strategic patterns that shaped the political action of the party: can the communist reaction to the impact in Italy of the Hungarian uprising be interpreted as a coherent implication of the communist preexisting and persisting strategy? In order to answer this question, it is necessary to reconstruct how the news coming from Hungary left an imprint on the “permanent interests” of the PCI, and how the communist apparatus reacted to the crisis. -

IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2008 Cineteca Del Comune Di Bologna

XXXVII Mostra Internazionale del Cinema Libero IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2008 Cineteca del Comune di Bologna XXII edizione / 22nd Edition Sabato 28 giugno - Sabato 5 luglio / Saturday 28 June - Saturday 5 July Questa edizione del festival è dedicata a Vittorio Martinelli This festival’s edition is dedicated to Vittorio Martinelli IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2008 Via Azzo Gardino, 65 - tel. 051 219 48 14 - fax 051 219 48 21 - cine- XXII edizione [email protected] Segreteria aperta dalle 9 alle 18 dal 28 giugno al 5 luglio / Secretariat Con il contributo di / With the financial support of: open June 28th - July 5th -from 9 am to 6 pm Comune di Bologna - Settore Cultura e Rapporti con l'Università •Cinema Lumière - Via Azzo Gardino, 65 - tel. 051 219 53 11 Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio in Bologna •Cinema Arlecchino - Via Lame, 57 - tel. 051 52 21 75 Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali - Direzione Generale per il Cinema Modalità di traduzione / Translation services: Regione Emilia-Romagna - Assessorato alla Cultura Tutti i film delle serate in Piazza Maggiore e le proiezioni presso il Programma MEDIA+ dell’Unione Europea Cinema Arlecchino hanno sottotitoli elettronici in italiano e inglese Tutte le proiezioni e gli incontri presso il Cinema Lumière sono tradot- Con la collaborazione di / In association with: ti in simultanea in italiano e inglese Fondazione Teatro Comunale di Bologna All evening screenings in Piazza Maggiore, as well as screenings at the L’Immagine Ritrovata Cinema Arlecchino, will be translated into Italian