Acharacter-Based Constructional Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L%- (2- V%- 2>$?- GA- (R- $- >A/- +- 2#?- 0- =?- 1A2- I3- .R%- 8J?- L- 2- 28$?- ?R,

!, ,L%- (2- v%- 2>$?- GA- (R- $- >A/- +- 2#?- 0- =?- 1A2- i3- .R%- 8J?- L- 2- 28$?- ?R, ,, The Exceedingly Concise Ritual of Confession of Downfalls from Bodhichitta called The Complete Purification of Karmic Obscurations !, ]- 3- .%- 2&R3- w/- :.?- .0=- >G:A- o=- 0R- =- K$- :5=- =R, LA MA DANG CHOM DEN DE PAL SHAKYE GYAL PO LA CHAG TSAL LO Homage to the Guru and the Bhagavan, the Glorious King of the Shakyas! ,.J:%- :R- {R=- IA- !R/- 0- ,$?- eJ- &/- .J- *A.- :1$?- 0- .!R/- 3(R$- 2lJ$?- 0:A- :.?- 0- *J<- 28A- 0- *J<- :#R<- IA?- 8?- 0:A- 3.R<- L%- 2- .J:A- v%- 2- 2>$?- 0:A- ,2?- 3(R$- +- I<- 0- 1%- 0R- $?3- 0- 8J?- H.- 0<- &/- $?%?- 0- :.A- *A.- ,J$- (J/- 0- 3,:- .$- $A?- >A/- +- ,$?- 2lA?- (J<- 36.- $>A?- :1$?- 0- [- 12- ?R$?- :1$?- 2R.- GA- 0E- P2- .- 3?- :PJ=- DA!- o?- 2#?- .- 3- 8A$- 36.- :.$- 0- .%- , :1$?- ;=- .:%- 3.R- =$?- GA- (R- $- .%- , }$?- =$?- GA- 12- ,2?- aR2- .0R/- /$- 0R- 0:A- 82?- GA?- 36.- 0- ?R$?- &A- <A$?- ;R.- :.$- 0<- 2gJ/- $%?- <A:A- OR.- :.A<- .$J- 2:A- 2>J?- $*J/- #- &A$- $A?- LA/- _2?- 28A- {R<- ?R$?- (/- ]:A- (R- $- =- 1<- 2!2- GA- (R- $- 36.- 0- .%- , :$:- 8A$- $A?- o- $<- 0E- (J/- >- <A- 0- Q- /?- 2o.- 0:A- eJ?- $/%- $A- (R- $- =- 2gJ/- /?- L- o.- =$?- GA- 12- ,2?- .%- , #- &A$- $A?- aR2- .0R/- (J/- 0R- 0E- :L%- $/?- GA?- 36.- 0:A- g- /$- ;A.- 28A/- /R<- 2:A- KA- 12- =- 2gJ/- 0:A- 2.J- $>J$?- ?R- s:A - 12- ,2?- .%- zR- |R- ?R$?- $- 5S$?- >A$- 36.- 0<- $%- 2- 3,:- .$- G%- #%?- .%- :UJ=- 8A%- LA/- _2?- k.- .- L%- 2- #R- /<- %J?- 0?- <%- $A- *3?- =J/- IA?- tR$- /- :.R.-0:A- .R/- :P2- %J?- :2:- 8A$- ;/- = A , In this regard, our teacher, the compassionate Buddha, expounded on a certain sutra called The Sutra of the Three Heaps, which is the supreme method for confessing downfalls, a practice in the twenty-fourth compendium of the exalted sutra entitled The Stack of Jewels, requested by Nyerkhor. -

Unicode Request for Cyrillic Modifier Letters Superscript Modifiers

Unicode request for Cyrillic modifier letters L2/21-107 Kirk Miller, [email protected] 2021 June 07 This is a request for spacing superscript and subscript Cyrillic characters. It has been favorably reviewed by Sebastian Kempgen (University of Bamberg) and others at the Commission for Computer Supported Processing of Medieval Slavonic Manuscripts and Early Printed Books. Cyrillic-based phonetic transcription uses superscript modifier letters in a manner analogous to the IPA. This convention is widespread, found in both academic publication and standard dictionaries. Transcription of pronunciations into Cyrillic is the norm for monolingual dictionaries, and Cyrillic rather than IPA is often found in linguistic descriptions as well, as seen in the illustrations below for Slavic dialectology, Yugur (Yellow Uyghur) and Evenki. The Great Russian Encyclopedia states that Cyrillic notation is more common in Russian studies than is IPA (‘Transkripcija’, Bol’šaja rossijskaja ènciplopedija, Russian Ministry of Culture, 2005–2019). Unicode currently encodes only three modifier Cyrillic letters: U+A69C ⟨ꚜ⟩ and U+A69D ⟨ꚝ⟩, intended for descriptions of Baltic languages in Latin script but ubiquitous for Slavic languages in Cyrillic script, and U+1D78 ⟨ᵸ⟩, used for nasalized vowels, for example in descriptions of Chechen. The requested spacing modifier letters cannot be substituted by the encoded combining diacritics because (a) some authors contrast them, and (b) they themselves need to be able to take combining diacritics, including diacritics that go under the modifier letter, as in ⟨ᶟ̭̈⟩BA . (See next section and e.g. Figure 18. ) In addition, some linguists make a distinction between spacing superscript letters, used for phonetic detail as in the IPA tradition, and spacing subscript letters, used to denote phonological concepts such as archiphonemes. -

The Analects of Confucius

The analecTs of confucius An Online Teaching Translation 2015 (Version 2.21) R. Eno © 2003, 2012, 2015 Robert Eno This online translation is made freely available for use in not for profit educational settings and for personal use. For other purposes, apart from fair use, copyright is not waived. Open access to this translation is provided, without charge, at http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23420 Also available as open access translations of the Four Books Mencius: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23421 Mencius: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23423 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: An Online Teaching Translation http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23422 The Great Learning and The Doctrine of the Mean: Translation, Notes, and Commentary http://hdl.handle.net/2022/23424 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i MAPS x BOOK I 1 BOOK II 5 BOOK III 9 BOOK IV 14 BOOK V 18 BOOK VI 24 BOOK VII 30 BOOK VIII 36 BOOK IX 40 BOOK X 46 BOOK XI 52 BOOK XII 59 BOOK XIII 66 BOOK XIV 73 BOOK XV 82 BOOK XVI 89 BOOK XVII 94 BOOK XVIII 100 BOOK XIX 104 BOOK XX 109 Appendix 1: Major Disciples 112 Appendix 2: Glossary 116 Appendix 3: Analysis of Book VIII 122 Appendix 4: Manuscript Evidence 131 About the title page The title page illustration reproduces a leaf from a medieval hand copy of the Analects, dated 890 CE, recovered from an archaeological dig at Dunhuang, in the Western desert regions of China. The manuscript has been determined to be a school boy’s hand copy, complete with errors, and it reproduces not only the text (which appears in large characters), but also an early commentary (small, double-column characters). -

A Dictionary of Chinese Characters: Accessed by Phonetics

A dictionary of Chinese characters ‘The whole thrust of the work is that it is more helpful to learners of Chinese characters to see them in terms of sound, than in visual terms. It is a radical, provocative and constructive idea.’ Dr Valerie Pellatt, University of Newcastle. By arranging frequently used characters under the phonetic element they have in common, rather than only under their radical, the Dictionary encourages the student to link characters according to their phonetic. The system of cross refer- encing then allows the student to find easily all the characters in the Dictionary which have the same phonetic element, thus helping to fix in the memory the link between a character and its sound and meaning. More controversially, the book aims to alleviate the confusion that similar looking characters can cause by printing them alongside each other. All characters are given in both their traditional and simplified forms. Appendix A clarifies the choice of characters listed while Appendix B provides a list of the radicals with detailed comments on usage. The Dictionary has a full pinyin and radical index. This innovative resource will be an excellent study-aid for students with a basic grasp of Chinese, whether they are studying with a teacher or learning on their own. Dr Stewart Paton was Head of the Department of Languages at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, from 1976 to 1981. A dictionary of Chinese characters Accessed by phonetics Stewart Paton First published 2008 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. -

44 44 44 44 44 44 42 42 42 42 42 42 42 42 42 44

Nº 5 Ныне отпущаеши (киевского распева) Сергей Рахманинов Медленно 4 2 4 4 4 4 Сопрано 4 2 4 4 4 4 ppp 4 2 4 4 4 4 Ны не от пу ща е ши ра ба Тво е Альтъ Ny ne ot pu shcha ye shi ra ba Tvo ye ppp 4 2 4 4 4 4 Ны не от пу ща е ши ра ба Тво е Ny ne ot pu shcha ye shi ra ba Tvo ye Теноръ p 1 соло 4 2 4 8 4 4 4 Ны не от пуща е ши раба Тво е го, Вла ды ко, Ny ne otpushcha yeshi raba Tvoye go Vla dy ko, ppp 4 2 4 8 4 4 4 Ны не от пу ща е ши ра ба Тво е Теноръ Ny ne ot pu shcha ye shi ra ba Tvo ye 4 2 4 8 4 4 4 + 4 2 4 4 4 4 Басъ 4 2 4 4 4 4 1 Зтот голос может быть заменен двумя тремя голосами в унисон первых теноров хора. + исполнятся с эакрытым ртом. Copyright © 2014 Брайан Майкл Эймс Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 license 2 7 Ap Ны не от пу ща е ши раба Тво е С Ny ne otpu shcha yeshi raba Tvoye p Ны не от пу ща е ши раба Тво е Ny ne otpu shcha yeshi raba Tvoye го, Вла ды ко, по гла го лу Тво е му, А go Vla dy ko, po gla go lu Tvo ye mu, го, Вла ды ко, по гла го лу Тво е му, go Vla dy ko, po gla go lu Tvo ye mu, mf mf 8 погла го лу Тво е му, с ми ром, я ко видеста о чи мо po gla go lu Tvo ye mu, s mi rom; Ya ko vi desta o chi mo 8 го, Вла ды ко, по гла го лу Тво е му, Т -

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Halh Mongolian As Spoken in MONGOLIA

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Halh Mongolian as Spoken in MONGOLIA Halh Mongolian, also known as Khalkha (or Xalxa) Mongolian, is a Mongolic language spoken in Mongolia. It has approximately 3 million speakers. 1. Special handling of dialects There are several Mongolic languages or dialects which are mutually intelligible. These include Chakhar and Ordos Mongol, both spoken in the Inner Mongolia region of China. Their status as separate languages is a matter of dispute (Rybatzki 2003). Halh Mongolian is the only Mongolian dialect spoken by the ethnic Mongolian majority in Mongolia. Mongolian speakers from outside Mongolia were not included in this data collection; only Halh Mongolian was collected. 2. Deviation from native-speaker principle No deviation, only native speakers of Halh Mongolian in Mongolia were collected. 3. Special handling of spelling None. 4. Description of character set used for orthographic transcription Mongolian has historically been written in a large variety of scripts. A Latin alphabet was introduced in 1941, but is no longer current (Grenoble, 2003). Today, the classic Mongolian script is still used in Inner Mongolia, but the official standard spelling of Halh Mongolian uses Mongolian Cyrillic. This is also the script used for all educational purposes in Mongolia, and therefore the script which was used for this project. It consists of the standard Cyrillic range (Ux0410-Ux044F, Ux0401, and Ux0451) plus two extra characters, Ux04E8/Ux04E9 and Ux04AE/Ux04AF (see also the table in Section 5.1). 5. Description of Romanization scheme The table in Section 5.1 shows Appen's Mongolian Romanization scheme, which is fully reversible. -

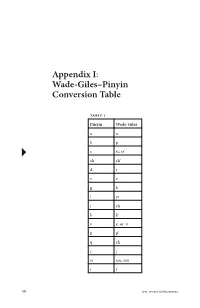

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 1 Pinyin Wade-Giles aa bp c ts’, tz’ ch ch’ dt ee gk iyi jch kk’ oe or o pp’ qch rj si ssu, szu tt’ 58 DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 59 xhs yi i yu u, yu you yu z ts, tz zh ch zi tzu -i (zhi) -ih (chih) -ie (lie) -ieh (lieh) -r (er) rh (erh) Examples jiang chiang zhiang ch’iang zi tzu zhi chih cai tsai Zhu Xi Chu Hsi Xunzi Hsün Tzu qing ch’ing xue hsüeh DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 60 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 2 Wade–Giles Pinyin aa ch’ ch ch j ch q ch zh ee e or oo ff hh hs x iyi -ieh (lieh) -ie (lie) -ih (chih) -i (zhi) jr kg k’ k pb p’ p rh (erh) -r (er) ssu, szu si td t’ t ts’, tz’ c ts, tz z tzu zi u, yu u yu you DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 61 Examples chiang jiang ch’iang zhiang ch‘ing qing chih zhi Chu Hsi Zhu Xi hsüeh xue Hsün Tzu Xunzi tsai cai tzu zi DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix II: Concordance of Key Philosophical Terms ⠅ai (To love) 1.5, 1.6, 3.17, 12.10, 12.22, 14.7, 17.4, 17.21 (9) 䘧 dao (Way, Path, Road, The Way, To tread a path, To speak, Doctrines, etc.) 1.2, 1.5, 1.11, 1.12, 1.14, 1.15, 2.3, 3.16, 3.24, 4.5, 4.8, 4.9, 4.15, 4.20, 5.2, 5.7, 5.13, 5.16, 5.21, 6.12, 6.17, 6.24, 7.6, 8.4, 8.7, 8.13, 9.12, 9.27, 9.30, 11.20, 11.24, 12.19, 12.23, 13.25, 14.1, 14.3, 14.19, 14.28, 14.36, 15.7, 15.25, 15.29, 15.32, 15.40, 15.42, 16.2, 16.5, 16.11, 17.4, 17.14, 18.2, 18.5, 18.7, 19.2, 19.4, 19.7, 19.12, 19.19, 19.22, 19.25. -

![Arxiv:2010.05019V1 [Cond-Mat.Supr-Con] 10 Oct 2020 Clrectto Ihu Hreo Electric a Or Is Charge fluctuations Without the Amplitude Excitation Gap](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1311/arxiv-2010-05019v1-cond-mat-supr-con-10-oct-2020-clrectto-ihu-hreo-electric-a-or-is-charge-uctuations-without-the-amplitude-excitation-gap-2421311.webp)

Arxiv:2010.05019V1 [Cond-Mat.Supr-Con] 10 Oct 2020 Clrectto Ihu Hreo Electric a Or Is Charge fluctuations Without the Amplitude Excitation Gap

Band-Selective Third-Harmonic Generation in Superconducting MgB2: Evidence for Higgs Amplitude Mode in the Dirty Limit Sergey Kovalev,1 Tao Dong,2,3, ∗ Li-Yu Shi,3 Chris Reinhoffer,4 Tie-Quan Xu,5 Hong-Zhang Wang,5 Yue Wang,5 Zi-Zhao Gan,5 Semyon Germanskiy,4 Jan-Christoph Deinert,1 Igor Ilyakov,1 Paul H. M. van Loosdrecht,4 Dong Wu,3 Nan-Lin Wang,3, 6 Jure Demsar,2 and Zhe Wang7, 4, 1, † 1Institute of Radiation Physics, Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf, 01328 Dresden, Germany 2Institute of Physics, Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz, 55128 Mainz, Germany 3International Center for Quantum Materials, School of Physics, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China 4Institute of Physics II, University of Cologne, 50937 Cologne, Germany 5Applied Superconductivity Center and State Key Laboratory for Mesoscopic Physics, School of Physics, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China 6Collaborative Innovation Center of Quantum Matter, Beijing, China 7Fakult¨at Physik, Technische Universit¨at Dortmund, 44221 Dortmund, Germany (Dated: October 13, 2020) We report on time-resolved linear and nonlinear terahertz spectroscopy of the two-band superconductor MgB2 with the superconducting transition temperature Tc ≈ 36 K. Third-harmonic generation (THG) is observed below Tc by driving the system with intense narrowband THz pulses. For the pump-pulse frequencies f = 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 THz, temperature-dependent evolution of the THG signals exhibits a resonance maximum at the temperature where 2 f = 2∆π(T), for the dirty-limit superconducting gap 2∆π = 1.03 THz at 4 K. In contrast, for f = 0.6 and 0.7 THz with 2 f > 2∆π, the THG intensity increases monotonically with decreasing temperature. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscr^ Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscr^ has been reproduced from the microfiliii master. UMI films the text directty from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dqiendent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photogrsqths, print bleedthrough, substandard m argins, and inqnoper alignment can adversety affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note win indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with sm all overkq)s. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations aiq>earing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Nmnber OSOTTTS Situation types and aspectual classes of verbs in Mandarin Chinese He, Baoshang, Ph D. Th« Ohio State UaWanity, 1902 UMI 300 N. -

Cyrillic # Version Number

############################################################### # # TLD: xn--j1aef # Script: Cyrillic # Version Number: 1.0 # Effective Date: July 1st, 2011 # Registry: Verisign, Inc. # Address: 12061 Bluemont Way, Reston VA 20190, USA # Telephone: +1 (703) 925-6999 # Email: [email protected] # URL: http://www.verisigninc.com # ############################################################### ############################################################### # # Codepoints allowed from the Cyrillic script. # ############################################################### U+0430 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER A U+0431 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER BE U+0432 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER VE U+0433 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER GE U+0434 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER DE U+0435 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER IE U+0436 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZHE U+0437 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZE U+0438 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER II U+0439 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHORT II U+043A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KA U+043B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EL U+043C # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EM U+043D # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EN U+043E # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER O U+043F # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER PE U+0440 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ER U+0441 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ES U+0442 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TE U+0443 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER U U+0444 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EF U+0445 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KHA U+0446 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TSE U+0447 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER CHE U+0448 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHA U+0449 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHCHA U+044A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER HARD SIGN U+044B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER YERI U+044C # CYRILLIC -

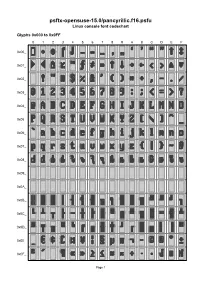

Psftx-Opensuse-15.0/Pancyrillic.F16.Psfu Linux Console Font Codechart

psftx-opensuse-15.0/pancyrillic.f16.psfu Linux console font codechart Glyphs 0x000 to 0x0FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x00_ 0x01_ 0x02_ 0x03_ 0x04_ 0x05_ 0x06_ 0x07_ 0x08_ 0x09_ 0x0A_ 0x0B_ 0x0C_ 0x0D_ 0x0E_ 0x0F_ Page 1 Glyphs 0x100 to 0x1FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x10_ 0x11_ 0x12_ 0x13_ 0x14_ 0x15_ 0x16_ 0x17_ 0x18_ 0x19_ 0x1A_ 0x1B_ 0x1C_ 0x1D_ 0x1E_ 0x1F_ Page 2 Font information 0x017 U+221E INFINITY Filename: psftx-opensuse-15.0/pancyrillic.f16.p 0x018 U+2191 UPWARDS ARROW sfu PSF version: 1 0x019 U+2193 DOWNWARDS ARROW Glyph size: 8 × 16 pixels 0x01A U+2192 RIGHTWARDS ARROW Glyph count: 512 Unicode font: Yes (mapping table present) 0x01B U+2190 LEFTWARDS ARROW 0x01C U+2039 SINGLE LEFT-POINTING Unicode mappings ANGLE QUOTATION MARK 0x000 U+FFFD REPLACEMENT 0x01D U+2040 CHARACTER TIE CHARACTER 0x01E U+25B2 BLACK UP-POINTING 0x001 U+2022 BULLET TRIANGLE 0x002 U+25C6 BLACK DIAMOND, 0x01F U+25BC BLACK DOWN-POINTING U+2666 BLACK DIAMOND SUIT TRIANGLE 0x003 U+2320 TOP HALF INTEGRAL 0x020 U+0020 SPACE 0x004 U+2321 BOTTOM HALF INTEGRAL 0x021 U+0021 EXCLAMATION MARK 0x005 U+2013 EN DASH 0x022 U+0022 QUOTATION MARK 0x006 U+2014 EM DASH 0x023 U+0023 NUMBER SIGN 0x007 U+2026 HORIZONTAL ELLIPSIS 0x024 U+0024 DOLLAR SIGN 0x008 U+201A SINGLE LOW-9 QUOTATION 0x025 U+0025 PERCENT SIGN MARK 0x026 U+0026 AMPERSAND 0x009 U+201E DOUBLE LOW-9 QUOTATION MARK 0x027 U+0027 APOSTROPHE 0x00A U+2018 LEFT SINGLE QUOTATION 0x028 U+0028 LEFT PARENTHESIS MARK 0x00B U+2019 RIGHT SINGLE QUOTATION 0x029 U+0029 RIGHT PARENTHESIS MARK 0x02A U+002A ASTERISK -

Filial Piety in Ancient Judaism and Early Confucianism

Filial Piety in Ancient Judaism and Early Confucianism Youde Fu Descartes once vividly compared philosophy, the main form of human knowledge, to a tree. For him, “the whole of philosophy is like a tree. The roots are metaphysics, the trunk is physics, and the branches emerging from the trunk are all the other sciences, which may be reduced to three principal ones, namely medicine, mechanics and morals.”1Inspired by Descartes, here I compare Judaism and Confucianism to two knowledge trees. In Judaism, the root is the faith of the transcendent God; the trunk is composed of the ideas of “chosen people” and prophecies, which connect God and Jewish people; the branches and the fruits are the Jewish law system – the Torah. As for Confucianism, the root may be regarded as the theological conceptions of heaven (天)、 heavenly destiny (天命) andthe way of heaven (天道);the trunk is the theories of the relationship between Heaven and Man, human heart andnature (心性学说), the idea of sages who functioned as the knowers and transmitters of the Heavenly Way; the branches and the fruits are Confucian ethical principles and rites, such as the principle of reciprocity (忠恕之道, golden rule), loving father (父慈),filial son (子孝), kind husband (夫和), submissive wife (妻顺), friendly elder-brother (兄友), respectful younger-brother (弟恭,di gong), righteous friend (友义), honorable monarch (君敬), loyal minister (臣忠), etc. Descartes also said it was not from the root, nor from the trunk, but just from the tip of branches that we picked the fruits.2 This indicates that though fruits from branches are not the essences of a tree, they are the purposes and the products.