STUDENT VOLUNTEERING at BUSINESS EVENTS in CHINA: MOTIVATIONS and CONCEPTUALIZATION by Hongxia Qi a Thesis Submitted to the Vi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L%- (2- V%- 2>$?- GA- (R- $- >A/- +- 2#?- 0- =?- 1A2- I3- .R%- 8J?- L- 2- 28$?- ?R,

!, ,L%- (2- v%- 2>$?- GA- (R- $- >A/- +- 2#?- 0- =?- 1A2- i3- .R%- 8J?- L- 2- 28$?- ?R, ,, The Exceedingly Concise Ritual of Confession of Downfalls from Bodhichitta called The Complete Purification of Karmic Obscurations !, ]- 3- .%- 2&R3- w/- :.?- .0=- >G:A- o=- 0R- =- K$- :5=- =R, LA MA DANG CHOM DEN DE PAL SHAKYE GYAL PO LA CHAG TSAL LO Homage to the Guru and the Bhagavan, the Glorious King of the Shakyas! ,.J:%- :R- {R=- IA- !R/- 0- ,$?- eJ- &/- .J- *A.- :1$?- 0- .!R/- 3(R$- 2lJ$?- 0:A- :.?- 0- *J<- 28A- 0- *J<- :#R<- IA?- 8?- 0:A- 3.R<- L%- 2- .J:A- v%- 2- 2>$?- 0:A- ,2?- 3(R$- +- I<- 0- 1%- 0R- $?3- 0- 8J?- H.- 0<- &/- $?%?- 0- :.A- *A.- ,J$- (J/- 0- 3,:- .$- $A?- >A/- +- ,$?- 2lA?- (J<- 36.- $>A?- :1$?- 0- [- 12- ?R$?- :1$?- 2R.- GA- 0E- P2- .- 3?- :PJ=- DA!- o?- 2#?- .- 3- 8A$- 36.- :.$- 0- .%- , :1$?- ;=- .:%- 3.R- =$?- GA- (R- $- .%- , }$?- =$?- GA- 12- ,2?- aR2- .0R/- /$- 0R- 0:A- 82?- GA?- 36.- 0- ?R$?- &A- <A$?- ;R.- :.$- 0<- 2gJ/- $%?- <A:A- OR.- :.A<- .$J- 2:A- 2>J?- $*J/- #- &A$- $A?- LA/- _2?- 28A- {R<- ?R$?- (/- ]:A- (R- $- =- 1<- 2!2- GA- (R- $- 36.- 0- .%- , :$:- 8A$- $A?- o- $<- 0E- (J/- >- <A- 0- Q- /?- 2o.- 0:A- eJ?- $/%- $A- (R- $- =- 2gJ/- /?- L- o.- =$?- GA- 12- ,2?- .%- , #- &A$- $A?- aR2- .0R/- (J/- 0R- 0E- :L%- $/?- GA?- 36.- 0:A- g- /$- ;A.- 28A/- /R<- 2:A- KA- 12- =- 2gJ/- 0:A- 2.J- $>J$?- ?R- s:A - 12- ,2?- .%- zR- |R- ?R$?- $- 5S$?- >A$- 36.- 0<- $%- 2- 3,:- .$- G%- #%?- .%- :UJ=- 8A%- LA/- _2?- k.- .- L%- 2- #R- /<- %J?- 0?- <%- $A- *3?- =J/- IA?- tR$- /- :.R.-0:A- .R/- :P2- %J?- :2:- 8A$- ;/- = A , In this regard, our teacher, the compassionate Buddha, expounded on a certain sutra called The Sutra of the Three Heaps, which is the supreme method for confessing downfalls, a practice in the twenty-fourth compendium of the exalted sutra entitled The Stack of Jewels, requested by Nyerkhor. -

Unicode Request for Cyrillic Modifier Letters Superscript Modifiers

Unicode request for Cyrillic modifier letters L2/21-107 Kirk Miller, [email protected] 2021 June 07 This is a request for spacing superscript and subscript Cyrillic characters. It has been favorably reviewed by Sebastian Kempgen (University of Bamberg) and others at the Commission for Computer Supported Processing of Medieval Slavonic Manuscripts and Early Printed Books. Cyrillic-based phonetic transcription uses superscript modifier letters in a manner analogous to the IPA. This convention is widespread, found in both academic publication and standard dictionaries. Transcription of pronunciations into Cyrillic is the norm for monolingual dictionaries, and Cyrillic rather than IPA is often found in linguistic descriptions as well, as seen in the illustrations below for Slavic dialectology, Yugur (Yellow Uyghur) and Evenki. The Great Russian Encyclopedia states that Cyrillic notation is more common in Russian studies than is IPA (‘Transkripcija’, Bol’šaja rossijskaja ènciplopedija, Russian Ministry of Culture, 2005–2019). Unicode currently encodes only three modifier Cyrillic letters: U+A69C ⟨ꚜ⟩ and U+A69D ⟨ꚝ⟩, intended for descriptions of Baltic languages in Latin script but ubiquitous for Slavic languages in Cyrillic script, and U+1D78 ⟨ᵸ⟩, used for nasalized vowels, for example in descriptions of Chechen. The requested spacing modifier letters cannot be substituted by the encoded combining diacritics because (a) some authors contrast them, and (b) they themselves need to be able to take combining diacritics, including diacritics that go under the modifier letter, as in ⟨ᶟ̭̈⟩BA . (See next section and e.g. Figure 18. ) In addition, some linguists make a distinction between spacing superscript letters, used for phonetic detail as in the IPA tradition, and spacing subscript letters, used to denote phonological concepts such as archiphonemes. -

44 44 44 44 44 44 42 42 42 42 42 42 42 42 42 44

Nº 5 Ныне отпущаеши (киевского распева) Сергей Рахманинов Медленно 4 2 4 4 4 4 Сопрано 4 2 4 4 4 4 ppp 4 2 4 4 4 4 Ны не от пу ща е ши ра ба Тво е Альтъ Ny ne ot pu shcha ye shi ra ba Tvo ye ppp 4 2 4 4 4 4 Ны не от пу ща е ши ра ба Тво е Ny ne ot pu shcha ye shi ra ba Tvo ye Теноръ p 1 соло 4 2 4 8 4 4 4 Ны не от пуща е ши раба Тво е го, Вла ды ко, Ny ne otpushcha yeshi raba Tvoye go Vla dy ko, ppp 4 2 4 8 4 4 4 Ны не от пу ща е ши ра ба Тво е Теноръ Ny ne ot pu shcha ye shi ra ba Tvo ye 4 2 4 8 4 4 4 + 4 2 4 4 4 4 Басъ 4 2 4 4 4 4 1 Зтот голос может быть заменен двумя тремя голосами в унисон первых теноров хора. + исполнятся с эакрытым ртом. Copyright © 2014 Брайан Майкл Эймс Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 license 2 7 Ap Ны не от пу ща е ши раба Тво е С Ny ne otpu shcha yeshi raba Tvoye p Ны не от пу ща е ши раба Тво е Ny ne otpu shcha yeshi raba Tvoye го, Вла ды ко, по гла го лу Тво е му, А go Vla dy ko, po gla go lu Tvo ye mu, го, Вла ды ко, по гла го лу Тво е му, go Vla dy ko, po gla go lu Tvo ye mu, mf mf 8 погла го лу Тво е му, с ми ром, я ко видеста о чи мо po gla go lu Tvo ye mu, s mi rom; Ya ko vi desta o chi mo 8 го, Вла ды ко, по гла го лу Тво е му, Т -

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Halh Mongolian As Spoken in MONGOLIA

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Halh Mongolian as Spoken in MONGOLIA Halh Mongolian, also known as Khalkha (or Xalxa) Mongolian, is a Mongolic language spoken in Mongolia. It has approximately 3 million speakers. 1. Special handling of dialects There are several Mongolic languages or dialects which are mutually intelligible. These include Chakhar and Ordos Mongol, both spoken in the Inner Mongolia region of China. Their status as separate languages is a matter of dispute (Rybatzki 2003). Halh Mongolian is the only Mongolian dialect spoken by the ethnic Mongolian majority in Mongolia. Mongolian speakers from outside Mongolia were not included in this data collection; only Halh Mongolian was collected. 2. Deviation from native-speaker principle No deviation, only native speakers of Halh Mongolian in Mongolia were collected. 3. Special handling of spelling None. 4. Description of character set used for orthographic transcription Mongolian has historically been written in a large variety of scripts. A Latin alphabet was introduced in 1941, but is no longer current (Grenoble, 2003). Today, the classic Mongolian script is still used in Inner Mongolia, but the official standard spelling of Halh Mongolian uses Mongolian Cyrillic. This is also the script used for all educational purposes in Mongolia, and therefore the script which was used for this project. It consists of the standard Cyrillic range (Ux0410-Ux044F, Ux0401, and Ux0451) plus two extra characters, Ux04E8/Ux04E9 and Ux04AE/Ux04AF (see also the table in Section 5.1). 5. Description of Romanization scheme The table in Section 5.1 shows Appen's Mongolian Romanization scheme, which is fully reversible. -

![Arxiv:2010.05019V1 [Cond-Mat.Supr-Con] 10 Oct 2020 Clrectto Ihu Hreo Electric a Or Is Charge fluctuations Without the Amplitude Excitation Gap](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1311/arxiv-2010-05019v1-cond-mat-supr-con-10-oct-2020-clrectto-ihu-hreo-electric-a-or-is-charge-uctuations-without-the-amplitude-excitation-gap-2421311.webp)

Arxiv:2010.05019V1 [Cond-Mat.Supr-Con] 10 Oct 2020 Clrectto Ihu Hreo Electric a Or Is Charge fluctuations Without the Amplitude Excitation Gap

Band-Selective Third-Harmonic Generation in Superconducting MgB2: Evidence for Higgs Amplitude Mode in the Dirty Limit Sergey Kovalev,1 Tao Dong,2,3, ∗ Li-Yu Shi,3 Chris Reinhoffer,4 Tie-Quan Xu,5 Hong-Zhang Wang,5 Yue Wang,5 Zi-Zhao Gan,5 Semyon Germanskiy,4 Jan-Christoph Deinert,1 Igor Ilyakov,1 Paul H. M. van Loosdrecht,4 Dong Wu,3 Nan-Lin Wang,3, 6 Jure Demsar,2 and Zhe Wang7, 4, 1, † 1Institute of Radiation Physics, Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf, 01328 Dresden, Germany 2Institute of Physics, Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz, 55128 Mainz, Germany 3International Center for Quantum Materials, School of Physics, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China 4Institute of Physics II, University of Cologne, 50937 Cologne, Germany 5Applied Superconductivity Center and State Key Laboratory for Mesoscopic Physics, School of Physics, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China 6Collaborative Innovation Center of Quantum Matter, Beijing, China 7Fakult¨at Physik, Technische Universit¨at Dortmund, 44221 Dortmund, Germany (Dated: October 13, 2020) We report on time-resolved linear and nonlinear terahertz spectroscopy of the two-band superconductor MgB2 with the superconducting transition temperature Tc ≈ 36 K. Third-harmonic generation (THG) is observed below Tc by driving the system with intense narrowband THz pulses. For the pump-pulse frequencies f = 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 THz, temperature-dependent evolution of the THG signals exhibits a resonance maximum at the temperature where 2 f = 2∆π(T), for the dirty-limit superconducting gap 2∆π = 1.03 THz at 4 K. In contrast, for f = 0.6 and 0.7 THz with 2 f > 2∆π, the THG intensity increases monotonically with decreasing temperature. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscr^ Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscr^ has been reproduced from the microfiliii master. UMI films the text directty from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dqiendent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photogrsqths, print bleedthrough, substandard m argins, and inqnoper alignment can adversety affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note win indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with sm all overkq)s. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations aiq>earing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Nmnber OSOTTTS Situation types and aspectual classes of verbs in Mandarin Chinese He, Baoshang, Ph D. Th« Ohio State UaWanity, 1902 UMI 300 N. -

Cyrillic # Version Number

############################################################### # # TLD: xn--j1aef # Script: Cyrillic # Version Number: 1.0 # Effective Date: July 1st, 2011 # Registry: Verisign, Inc. # Address: 12061 Bluemont Way, Reston VA 20190, USA # Telephone: +1 (703) 925-6999 # Email: [email protected] # URL: http://www.verisigninc.com # ############################################################### ############################################################### # # Codepoints allowed from the Cyrillic script. # ############################################################### U+0430 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER A U+0431 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER BE U+0432 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER VE U+0433 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER GE U+0434 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER DE U+0435 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER IE U+0436 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZHE U+0437 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZE U+0438 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER II U+0439 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHORT II U+043A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KA U+043B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EL U+043C # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EM U+043D # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EN U+043E # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER O U+043F # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER PE U+0440 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ER U+0441 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ES U+0442 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TE U+0443 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER U U+0444 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EF U+0445 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KHA U+0446 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TSE U+0447 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER CHE U+0448 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHA U+0449 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHCHA U+044A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER HARD SIGN U+044B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER YERI U+044C # CYRILLIC -

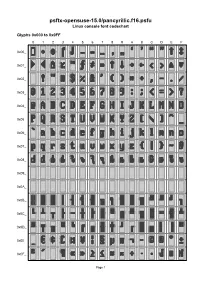

Psftx-Opensuse-15.0/Pancyrillic.F16.Psfu Linux Console Font Codechart

psftx-opensuse-15.0/pancyrillic.f16.psfu Linux console font codechart Glyphs 0x000 to 0x0FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x00_ 0x01_ 0x02_ 0x03_ 0x04_ 0x05_ 0x06_ 0x07_ 0x08_ 0x09_ 0x0A_ 0x0B_ 0x0C_ 0x0D_ 0x0E_ 0x0F_ Page 1 Glyphs 0x100 to 0x1FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x10_ 0x11_ 0x12_ 0x13_ 0x14_ 0x15_ 0x16_ 0x17_ 0x18_ 0x19_ 0x1A_ 0x1B_ 0x1C_ 0x1D_ 0x1E_ 0x1F_ Page 2 Font information 0x017 U+221E INFINITY Filename: psftx-opensuse-15.0/pancyrillic.f16.p 0x018 U+2191 UPWARDS ARROW sfu PSF version: 1 0x019 U+2193 DOWNWARDS ARROW Glyph size: 8 × 16 pixels 0x01A U+2192 RIGHTWARDS ARROW Glyph count: 512 Unicode font: Yes (mapping table present) 0x01B U+2190 LEFTWARDS ARROW 0x01C U+2039 SINGLE LEFT-POINTING Unicode mappings ANGLE QUOTATION MARK 0x000 U+FFFD REPLACEMENT 0x01D U+2040 CHARACTER TIE CHARACTER 0x01E U+25B2 BLACK UP-POINTING 0x001 U+2022 BULLET TRIANGLE 0x002 U+25C6 BLACK DIAMOND, 0x01F U+25BC BLACK DOWN-POINTING U+2666 BLACK DIAMOND SUIT TRIANGLE 0x003 U+2320 TOP HALF INTEGRAL 0x020 U+0020 SPACE 0x004 U+2321 BOTTOM HALF INTEGRAL 0x021 U+0021 EXCLAMATION MARK 0x005 U+2013 EN DASH 0x022 U+0022 QUOTATION MARK 0x006 U+2014 EM DASH 0x023 U+0023 NUMBER SIGN 0x007 U+2026 HORIZONTAL ELLIPSIS 0x024 U+0024 DOLLAR SIGN 0x008 U+201A SINGLE LOW-9 QUOTATION 0x025 U+0025 PERCENT SIGN MARK 0x026 U+0026 AMPERSAND 0x009 U+201E DOUBLE LOW-9 QUOTATION MARK 0x027 U+0027 APOSTROPHE 0x00A U+2018 LEFT SINGLE QUOTATION 0x028 U+0028 LEFT PARENTHESIS MARK 0x00B U+2019 RIGHT SINGLE QUOTATION 0x029 U+0029 RIGHT PARENTHESIS MARK 0x02A U+002A ASTERISK -

Caixin China General Services PMI Press Release 2020.9 Embargoed Until 0945 CST (0145 UTC) 9 October 2020

Caixin China General Services PMI Press Release 2020.9 Embargoed until 0945 CST (0145 UTC) 9 October 2020 Caixin China General Services PMI ™ Service sector growth accelerates during September Chinese services companies signalled another steep increase in business activity at the end of the third quarter, to signal a further recovery from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Growth was supported by China General Services Business Activity Index a marked rise in total new business, though new export work continued to decline. Nonetheless, the sustained rise in overall client demand led firms to sa, >50 = growth since previous month expand their payrolls for the second month in a row amid increased capacity pressures. Companies also retained a positive outlook regarding activity 70 over the year ahead, with business confidence improving since August. 65 60 Prices data meanwhile indicated that inflationary pressures eased, with both input costs and output prices rising at softer rates at the end of the third 55 quarter. 50 At 54.8 in September, the headline seasonally adjusted Business Activity 45 Index was up from 54.0 in August and signalled a fifth successive monthly 40 increase in service sector output. Notably, the rate of expansion was the 35 sharpest for three months and among the quickest recorded over the past 30 decade. 25 Supporting the further rise in overall business activity was a sustained 20 increase in total new business. Moreover, the rate of new order growth 2008 2020 accelerated since August and was solid overall. Panel members frequently mentioned that a further recovery of client demand following the pandemic and new project developments had boosted sales at the end of the third Sources: Caixin, IHS Markit quarter. -

Hushers for Vocal Quartet (SSMA)

hushers for vocal quartet (SSMA) Written for Quince Contemporary Vocal Ensemble by Warren Enström Program Notes: Hushers are four consonants in the Russian language characterized by their noisiness. In the Russian alphabet, these sounds are mostly tied to specific letters. In English, however, this noisy sounds are not tied specifically to letters, but to word and context. Think of the sh in sheep, the ch in chip, the ge in garage. In Russian, each of these sounds are represented by single letters: Щ (shcha), Ч (che), and Ж (zhe), respectively. Russian has one additional husher: Ш (sha). Sha is a fuller noise sound, similar to the sh in sharp. Because the English alphabet doesn’t foreground these sonic differences as clearly as the Russian alphabet does, it can be hard for English-speakers beginning to learn Russian to hear these letters (especially sha and shcha) apart. As I’ve been learning Russian, it’s been interesting to discover and practice these nuances. The human vocal tract provides astoundingly precise control over the sounds we produce, and in hushers, I explore these noisy consonants, their pitched counterparts, and the spaces in-between them. Performance Notes: hushers utilizes quarter tones, which are represented by the appropriate accidentals seen below. Three-quarter-tone flats are not be used. Quarter Tone Accidentals Second, measures that do not contain pitched material use a single line staff with x noteheads designating the rhythm to be performed. Third, phonemes are designated with three different markings. Lines that end with a bracket indicate that the phoneme ends at the end of the bracket. -

Negation and Aspect: a Comparative Study of Mandarin and Cantonese Varieties

Negation and Aspect: A comparative study of Mandarin and Cantonese varieties Chit Yu Lam Section of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics Hughes Hall University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 Negation and Aspect: A comparative study of Mandarin and Cantonese varieties Chit Yu LAM This dissertation examines the interaction between standard negation and aspect in Chinese under two conditions: bare negation showing negation-situation type compatibility, and negation with overt aspectual marKing. The comparative study of Beijing Mandarin, Taiwan Mandarin, Hong Kong Cantonese, and the previously unstudied Gaozhou Cantonese demonstrates that the aspectual sensitivity of negation is governed by more general structural properties than idiosyncratic aspectual selection requirements of the negators. In negative declaratives without aspectual marKing (bare negatives), Chapter 2 shows that where a variety has more than one standard negator, the distribution of the negators mostly creates systematic semantic contrast instead of any grammaticality consequence: Mandarin méiyǒu, Hong Kong Cantonese mou5 and Gaozhou Cantonese mau5 consistently offer a situation non-existent reading, while Mandarin bù and Hong Kong Cantonese m4 always involve a modality reading (habitual or volitional). Based on the relative distribution of negation and different types of adverbs, Chapter 4 suggests that all standard negators in the four Chinese varieties are generated in the outermost specifier of vP. The uniformity in negator position challenges previous accounts that méiyǒu and mou5 are higher in Asp, and urges a rethinKing of the nature of these negators. Following Croft’s (1991) Negative-Existential Cycle and supported by corpus data from Taiwan Mandarin, the chapter demonstrates that méiyǒu, mou5 and mau5 are standard negators developed from the negative existential predicate (non-existence of entities) and have now extended their function to verbal negation (non- existence of situations). -

Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N4199 L2/12-040

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4199 L2/12-040 2012-01-31 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation internationale de normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal to encode four Cyrillic characters in the BMP of the UCS Source: Michael Everson and Soslan Khubulov Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2012-01-31 1. Character additions. This document requests the addition of four new Cyrillic characters to the UCS. Two of these letters were introduced into the Ossetian alphabet in 1844 by Andreas Johan Sjögren. That alphabet was in use up to 1924 when the Latin script was adopted for Ossetian. There is a great deal of literature written during the 80 years when that orthography was in use. Both a capital and a small character are requested. Those same two letters and two more are attested in a Komi grammar from 1850. Thus the following four characters are requested: 052A Ԫ CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER DZZHE 052B ԫ CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER DZZHE • Ossetian, Komi 052C Ԭ CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER DCHE 052D ԭ CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER DCHE • Komi 2. Ordering. The relative position of these two letters (taking case pairing as read) is shown below. DZZHE follows immediately after ZHE and before ZHWE DCHE follows immediately after CHE and before TCHE 3. Unicode Character Properties. Character properties are proposed here. 052A;CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER DZZHE;Lu;0;L;;;;;N;;;;052B; 052B;CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER DZZHE;Ll;0;L;;;;;N;;;052A;;052A 052C;CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER DCHE;Lu;0;L;;;;;N;;;;052D; 052D;CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER DCHE;Ll;0;L;;;;;N;;;052C;;052C 1 Figures Figure 1.