T H E Wi Lson Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navy's More Colorjiul Admirals, the Guided Missile Frigate Clark Slides Down the Ways at Both Iron Works, Bath, Maine

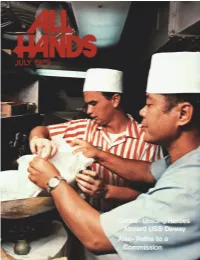

Named after one of the US. Navy's more colorjiul admirals, the guided missile frigate Clark slides down the ways at Both Iron Works, Bath, Maine. The 445-foot warship honors Admiral Joseph J. (Jocko) Clark of World War II fame. The ship, designed for defense against submarines, aircrafi and surface ships, was christened by the admiral's widow, Olga, of New York City. (Photo by Ron Farr.) ALL WIND6 MAGAZINE OF THE U.S. NAVY - 56th YEAR OF PUBLICATION JULY 1979 NUMBER 750 Chief of Naval Operations: ADM Thomas B. Hayward Chiefof Information: RADM David M. Cooney OIC Navy Internal Relations Act: CAPT Robert K. Lewis Jr. Features 6 FEEDING THE FLEET I Tracing Navy chow from hardtack to today's 'Think Thm' menus Page 30 THEY EAT BETTER ABOARD DEWEY THAN THEY DO AT HOME It takes a lot of pride to put out three good meals a da\T WHO GOES WHERE AND WHY There's more to detailing than just writrng orders ONE FOOT IN THE UNIVERSE Dedication of the Albert Einstein memorial at the Natlonal Academy of Sciences NAVAL AVIATION MUSEUM - PHASE II Second part of Pensacola's building program is complete 39 HIS EYES ARE ON OLYMPIC GOLD A competitor has only one shot at the rowing event this summer in Moscow PATHS TO A COMMISSION Page 39 Eighth in a series on Rights and Benefits Departments 2 Currents 20 Bearings 48 Mail Buoy Covers Front: Working side by side, USS Dewey's MSSN Gary LeFande (left) and MS1 Paulino Arnancio help turn ordinary food items into savory dishes. -

Fy2007 Fy2007

999557_Cov.qxd:Layout 1 10/25/07 12:56 PM Page 1 President’s Report President’s Report FY2007 FY2007 444 Green Street Gardner, MA 01440-1000 / USA (978) 632-6600 www.mwcc.edu 999557_Cov.qxd:Layout 1 10/25/07 12:56 PM Page 2 Start Near…Go Far 999557_Vellum:Layout 1 10/22/07 7:38 AM Page 1 As reflected in our slogan, we encourage Mount Wachusett Community College students to “Start near . Go far.” We help them to realize their potential, to follow their dreams . to literally go anywhere with the skills they gain here. We are a stepping stone for students to find who they really are, what their dreams really are, and to start fulfilling them. As an institution, we thrive on these same principles. Therefore, we pride ourselves on providing innovative programs, which often become best practices and models for the national and international community. MWCC now unfolds the results of the college’s first-ever capital campaign, which resulted in raising nearly $4 million. Because of the success of the capital campaign and the philanthropy of the community we serve, MWCC received the highest match from the state’s Endowment Incentive Matching program. We have now finished construction and opened the Garrison Center for Early Childhood Education, dedicated the college’s library to Leo and Theresa LaChance, and completed Phase I of library renovations. Furthermore, one of the individuals at the heart of this campaign, MWCC trustee and foundation board member Jim Garrison, received national recognition with a 2006 Benefactors Award from the Council for Resource Development for his dedication to the mission of MWCC. -

OCTOBER 2005 Home Office Science and Research Group

OCTOBER 2005 CHINA Home Office Science and Research Group COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE 1 OCTOBER 2005 CHINA Country of Origin Reports are produced by the Science & Research Group of the Home Office to provide caseworkers and others involved in processing asylum applications with accurate, balanced and up-to-date information about conditions in asylum seekers’ countries of origin. They contain general background information about the issues most commonly raised in asylum/human rights claims made in the UK. The reports are compiled from material produced by a wide range of recognised external information sources. They are not intended to be a detailed or comprehensive survey, nor do they contain Home Office opinion or policy. 2 Disclaimer: “This country of origin information report contains the most up-to-date publicly available information as at 31 August 2005. Older source material has been included where it contains relevant information not available in more recent documents.” OCTOBER 2005 CHINA Contents 1. Scope of document 1.1 2. Geography 2.1 Languages 2.5 Mandarin (Putonghua) 2.5 Pinyin translation system 2.6 Naming conventions 2.7 Tibetan names 2.8 Population 2.9 3. Economy 3.1 Shadow Banks 3.2 Poverty 3.4 The Environment 3.9 State owned enterprises (SOEs) 3.11 Unemployment 3.16 Currency 3.18 Corruption 3.20 Guanxi 3.26 Punishment of corrupt officials 3.28 4. History 4.1 1949-1976: The Mao Zedong era 4.1 1978-1989: Deng Xiaoping as paramount 4.3 leader Tiananmen Square protests (1989) 4.4 Post-Tiananmen Square 4.7 Jiang Zemin as core leader 4.9 Hu Jiantao: chairman of the board 4.10 5. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

Alumni Revue! This Issue Was Created Since It Was Decided to Publish a New Edition Every Other Year Beginning with SP 2017

AAlluummnnii RReevvuuee Ph.D. Program in Theatre The Graduate Center City University of New York Volume XIII (Updated) SP 2016 Welcome to the updated version of the thirteenth edition of our Alumni Revue! This issue was created since it was decided to publish a new edition every other year beginning with SP 2017. It once again expands our numbers and updates existing entries. Thanks to all of you who returned the forms that provided us with this information; please continue to urge your fellow alums to do the same so that the following editions will be even larger and more complete. For copies of the form, Alumni Information Questionnaire, please contact the editor of this revue, Lynette Gibson, Assistant Program Officer/Academic Program Coordinator, Ph.D. Program in Theatre, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10016-4309. You may also email her at [email protected]. Thank you again for staying in touch with us. We’re always delighted to hear from you! Jean Graham-Jones Executive Officer Hello Everyone: his is the updated version of the thirteenth edition of Alumni Revue. As always, I would like to thank our alumni for taking the time to send me T their updated information. I am, as always, very grateful to the Administrative Assistants, who are responsible for ensuring the entries are correctly edited. The Cover Page was done once again by James Armstrong, maybe he should be named honorary “cover-in-chief”. The photograph shows the exterior of Shakespeare’s Globe in London, England and was taken in August 2012. -

Lu Zhiqiang China Oceanwide

08 Investment.FIN.qxp_Layout 1 14/9/16 12:21 pm Page 81 Week in China China’s Tycoons Investment Lu Zhiqiang China Oceanwide Oceanwide Holdings, its Shenzhen-listed property unit, had a total asset value of Rmb118 billion in 2015. Hurun’s China Rich List He is the key ranked Lu as China’s 8th richest man in 2015 investor behind with a net worth of Rmb83 billlion. Minsheng Bank and Legend Guanxi Holdings A long-term ally of Liu Chuanzhi, who is known as the ‘godfather of Chinese entrepreneurs’, Oceanwide acquired a 29% stake in Legend Holdings (the parent firm of Lenovo) in 2009 from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences for Rmb2.7 billion. The transaction was symbolic as it marked the dismantling of Legend’s SOE status. Lu and Liu also collaborated to establish the exclusive Taishan Club in 1993, an unofficial association of entrepreneurs named after the most famous mountain in Shandong. Born in Shandong province in 1951, Lu In fact, according to NetEase Finance, it was graduated from the elite Shanghai university during the Taishan Club’s inaugural meeting – Fudan. His first job was as a technician with hosted by Lu in Shandong – that the idea of the Shandong Weifang Diesel Engine Factory. setting up a non-SOE bank was hatched and the proposal was thereafter sent to Zhu Getting started Rongji. The result was the establishment of Lu left the state sector to become an China Minsheng Bank in 1996. entrepreneur and set up China Oceanwide. Initially it focused on education and training, Minsheng takeover? but when the government initiated housing Oceanwide was one of the 59 private sector reform in 1988, Lu moved into real estate. -

Title: the Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher's Guide of 20Fh Century Physics

REPORT NSF GRANT #PHY-98143318 Title: The Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher’s Guide of 20fhCentury Physics DOE Patent Clearance Granted December 26,2000 Principal Investigator, Brian Schwartz, The American Physical Society 1 Physics Ellipse College Park, MD 20740 301-209-3223 [email protected] BACKGROUND The American Physi a1 Society s part of its centennial celebration in March of 1999 decided to develop a timeline wall chart on the history of 20thcentury physics. This resulted in eleven consecutive posters, which when mounted side by side, create a %foot mural. The timeline exhibits and describes the millstones of physics in images and words. The timeline functions as a chronology, a work of art, a permanent open textbook, and a gigantic photo album covering a hundred years in the life of the community of physicists and the existence of the American Physical Society . Each of the eleven posters begins with a brief essay that places a major scientific achievement of the decade in its historical context. Large portraits of the essays’ subjects include youthful photographs of Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and Richard Feynman among others, to help put a face on science. Below the essays, a total of over 130 individual discoveries and inventions, explained in dated text boxes with accompanying images, form the backbone of the timeline. For ease of comprehension, this wealth of material is organized into five color- coded story lines the stretch horizontally across the hundred years of the 20th century. The five story lines are: Cosmic Scale, relate the story of astrophysics and cosmology; Human Scale, refers to the physics of the more familiar distances from the global to the microscopic; Atomic Scale, focuses on the submicroscopic This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. -

Falun Gong in the United States: an Ethnographic Study Noah Porter University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 7-18-2003 Falun Gong in the United States: An Ethnographic Study Noah Porter University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Porter, Noah, "Falun Gong in the United States: An Ethnographic Study" (2003). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/1451 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FALUN GONG IN THE UNITED STATES: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY by NOAH PORTER A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: S. Elizabeth Bird, Ph.D. Michael Angrosino, Ph.D. Kevin Yelvington, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 18, 2003 Keywords: falungong, human rights, media, religion, China © Copyright 2003, Noah Porter TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES...................................................................................................................................iii LIST OF FIGURES................................................................................................................................. iv ABSTRACT........................................................................................................................................... -

WIC Template 13/9/16 11:52 Am Page IFC1

In a little over 35 years China’s economy has been transformed Week in China from an inefficient backwater to the second largest in the world. If you want to understand how that happened, you need to understand the people who helped reshape the Chinese business landscape. china’s tycoons China’s Tycoons is a book about highly successful Chinese profiles of entrepreneurs. In 150 easy-to- digest profiles, we tell their stories: where they came from, how they started, the big break that earned them their first millions, and why they came to dominate their industries and make billions. These are tales of entrepreneurship, risk-taking and hard work that differ greatly from anything you’ll top business have read before. 150 leaders fourth Edition Week in China “THIS IS STILL THE ASIAN CENTURY AND CHINA IS STILL THE KEY PLAYER.” Peter Wong – Deputy Chairman and Chief Executive, Asia-Pacific, HSBC Does your bank really understand China Growth? With over 150 years of on-the-ground experience, HSBC has the depth of knowledge and expertise to help your business realise the opportunity. Tap into China’s potential at www.hsbc.com/rmb Issued by HSBC Holdings plc. Cyan 611469_6006571 HSBC 280.00 x 170.00 mm Magenta Yellow HSBC RMB Press Ads 280.00 x 170.00 mm Black xpath_unresolved Tom Fryer 16/06/2016 18:41 [email protected] ${Market} ${Revision Number} 0 Title Page.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 6:36 pm Page 1 china’s tycoons profiles of 150top business leaders fourth Edition Week in China 0 Welcome Note.FIN.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 3:10 pm Page 2 Week in China China’s Tycoons Foreword By Stuart Gulliver, Group Chief Executive, HSBC Holdings alking around the streets of Chengdu on a balmy evening in the mid-1980s, it quickly became apparent that the people of this city had an energy and drive Wthat jarred with the West’s perception of work and life in China. -

Resolved by the Senate and House Of

906 PUBLIC LAW 90-541-0CT. I, 1968 [82 STAT. Public Law 90-541 October 1, 1968 JOINT RESOLUTION [H.J. Res, 1461] Making continuing appropriations for the fiscal year 1969, and for other purposes. Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatimes of tlie United Continuing ap propriations, States of America in Congress assernbled, That clause (c) of section 1969. 102 of the joint resolution of June 29, 1968 (Public Law 90-366), is Ante, p. 475. hereby further amended by striking out "September 30, 1968" and inserting in lieu thereof "October 12, 1968". Approved October 1, 1968. Public Law 90-542 October 2, 1968 AN ACT ------[S. 119] To proYide for a Xational Wild and Scenic Rivers System, and for other purPoses. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Wild and Scenic United States of America in Congress assembled, That (a) this Act Rivers Act. may be cited as the "vVild and Scenic Rivers Act". (b) It is hereby declared to be the policy of the United States that certain selected rivers of the Nation which, with their immediate environments, possess outstandin~ly remarkable scenic, recreational, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic, cultural, or other similar values, shall be preserved in free-flowing condition, and that they and their immediate environments shall be protected for the benefit and enjoy ment of l?resent and future generations. The Congress declares that the established national policy of dam and other construction at appro priate sections of the rivers of the United States needs to be com plemented by a policy that would preserve other selected rivers or sections thereof m their free-flowing condition to protect the water quality of such rivers and to fulfill other vital national conservation purposes. -

The Arts of Making Do and Working out in Beijing, China

What are friends for?: The arts of making do and working out in Beijing, China Michelle Yang Zhang Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2020 Michelle Yang Zhang All Rights Reserved Abstract What are friends for?: The arts of making do and working out in Beijing, China Michelle Yang Zhang Through a second look at the now twenty-five-year-old literature on guanxi, a form of reciprocal relationship making and using in China, I examine how the kinds of opportunities and challenges possible for young people intersect with who they know and how this has changed (with its own set of reflections on and consequences for a still-rapidly changing China) since China’s rural to urban transition. My dissertation project examines how young people in contemporary urban China form and produce guanxi ties (resource-full relationships) through the theoretical lens of practice and possibility, inspired by de Certeau’s conceptualization of practice, productive consumption, and strategies versus tactics (1984). Drawing on qualitative data gathered through participant observation and unstructured interviews, I sought to both describe and analyze when, where, and how social networks became consequential. Central to my methodology is an emphasis on people and their practices rather than the common sense categories used to describe them. The people in my field research were predominantly aged 18- 30 and came from a range of ethnic, professional, and education backgrounds. In so doing, I was able to examine the moments and contexts within which some people have opportunities and others do not, as well as when some are vulnerable while others are less so. -

The Politics of Photographic Representation in Postsocialist China

Staging the Future: The Politics of Photographic Representation in Postsocialist China by James David Poborsa A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by James David Poborsa 2018 Staging the Future - The Politics of Photographic Representation in Postsocialist China James David Poborsa Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This dissertation examines the changing nature of photographic representation in China from 1976 until the late 1990s, and argues that photography and photo criticism self-reflexively embodied the cultural politics of social and political liberalisation during this seminal period in Chinese history. Through a detailed examination of debates surrounding the limits of representation and intellectual liberalisation, this dissertation explores the history of social documentary, realist, and conceptual photography as a form of social critique. As a contribution to scholarly appraisals of the cultural politics of contemporary China, this dissertation aims to shed insight into the fraught and often contested politics of visuality which has characterized the evolution of photographic representation in the post-Mao period. The first chapter examines the politics of photographic representation in China from 1976 until 1982, and explores the politicisation of documentary realism as a means of promoting modernisation and reform. Chapter two traces the internationalisation