Bengali Bihari Muharram

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memo 2018 2018 1 Index

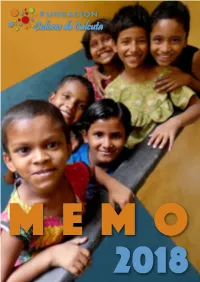

memo MEMO 2018 2018 1 INDEX WHO WE ARE Acknowledgement Letter 3 Our History 4 Where we Work: Pilkhana, The City of Joy” 5 Mission, Vision, Values and Principles 6 Colores de Calcuta Community 8 COOPERATION FOR DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Services 12 Beneficiaries 2018 14 Pilkhana Medical Centre 16 Medical Services 17 Economic Benefits 19 Hospital Accompaniment 19 Health Awareness Workshops 20 Collaboration with Public Health Programmes 20 Child Units: 24 Child Nutrition Programme 24 Nursery School 27 Anand Bhavan 30 Home for girls and teenage girls 30 Scholarship Programme and accompaniment to achieving an independent life 36 Women Artisans Group 37 AWARENESS RAISING AND VOLUNTEERING PROGRAMME FUNDRAISING AND COMMUNICATION Solidarity Events and Initiatives 40 Communication and Media 43 Collaborating Entities 44 TRANSPARENCY Origin and Use of Resources 46 2 COLORES DE CALCUTA FOUNDATION THANK YOU Dear friends, In this memo, we share the work carried out during 2018. A year in which the team made up of Colores de Calcuta Foundation and our counterpart Seva Sangh Samity has gained strength. A year in which our centres in Kolkata, the Medical Centre and Anand Bhavan, have continued to grow and consolidate their services. A year in which we have grown in our care capabilities, accompanying more than 27,000 beneficiaries in order to improve their quality of life. A year in which we have done a thorough analysis of our working model: a humanistic model of opportunities, capabilities and rights, focusing on people. All this has been possible thanks to all the people who work, participate, collaborate and make up theColores de Calcuta Community. -

Khan, Aliyah: Far from Mecca: Globalizing the Muslim Caribbean New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press 2020

International Journal of Latin American Religions (2020) 4:440–446 https://doi.org/10.1007/s41603-020-00118-y BOOK REVIEW Open Access Khan, Aliyah: Far From Mecca: Globalizing the Muslim Caribbean New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press 2020. ISBN 978-19788006641, 271p. Ken Chitwood1 Published online: 15 September 2020 # The Author(s) 2020 Introduction Brenda Flanagan’s 2009 novel Allah in the Islands tells the story of the lives, dreams, and social tensions of the residents of Rosehill, a community on the fictional “Santabella Island.” The novel centers around the protagonist Beatrice Salandy and her decision whether or not to leave Santabella, a lush and tropical Caribbean island only thinly veiled as real-life Trinidad. Weaving its way through the novel is Beatrice’s relationship with an “Afro-Santabellan” Muslim community that is critical of island politics and outspoken on behalf of the poor. Through first-hand narratives from Abdul—one of the members of the community and right-hand man to its leader, Haji—readers learn that the “Afro-Santabellan” Muslim community is planning a coup against the Santabellan government. This, in turn, is a thinly veiled reference to the real-life 1990 Jamaat al-Muslimeen coup. A key theme that runs throughout the book, and in contemporary Trinidad, is how the non-Muslim residents of Santabella view “Afro-Santabellan” Muslims. Situated between the island’s Black and Indian commu- nities, Flanagan writes how island residents react with a mixture of awe and opprobri- um to their Muslim neighbors. While it may seem strange to start a review of one book with a discussion of another, I would not have been aware of Flanagan’s work if it were not for Aliyah Khan. -

A Sociological Study of Street Children in Howrah

A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF STREET CHILDREN IN HOWRAH A Thesis submitted to the North Bengal University For the Award of Doctor of Philosophy In Sociology BY Subrata Mukherjee GUIDE Prof. RajatsubhraMukhopadhyay Department of Sociology North Bengal University October, 2016 DECLARATION I declare that the thesis entitled A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF STREET CHILDREN IN HOWRAH has been prepared by me under the guidance of Prof. Rajatsubhra Mukhopadhyay, Professor of Sociology Department, North Bengal University. No part of this thesis has formed the basis for award of my degree or fellowship previously. ( SUBRATA MUKHERJEE) Department of Sociology, North Bengal University, Dist. Darjeeling, West Bengal, 734013. DATE: i Abstract Introduction The problem of street children is basically manifestation of certain structural contradiction of the society. Although this problem is an universal phenomenon, it has become an issue of concern in present years as India has the largest population of street children in the world. Migrating to the city does not imply that street children will get extra wealth and prosperity. They are the product of urbanization and contribute to the urban informal economy in different capacity. They are the part of city life and urban economy. They not only provide labour to the informal economy but also get involved in many hazardous activities, being a part of the exploitation net work (production relation) in bourgeois system. An increasing amount of research describes that care and protection of street children are grim. The analysis of the data indicates that over the past decade the situation of such children has deteriorated. The poor children become poorer and the children from the lower middle class have become poorer. -

Metro Railway Kolkata Presentation for Advisory Board of Metro Railways on 29.6.2012

METRO RAILWAY KOLKATA PRESENTATION FOR ADVISORY BOARD OF METRO RAILWAYS ON 29.6.2012 J.K. Verma Chief Engineer 8/1/2012 1 Initial Survey for MTP by French Metro in 1949. Dum Dum – Tollygunge RTS project sanctioned in June, 1972. Foundation stone laid by Smt. Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India on December 29, 1972. First train rolled out from Esplanade to Bhawanipur (4 km) on 24th October, 1984. Total corridor under operation: 25.1 km Total extension projects under execution: 89 km. June 29, 2012 2 June 29, 2012 3 SEORAPFULI BARRACKPUR 12.5KM SHRIRAMPUR Metro Projects In Kolkata BARRACKPUR TITAGARH TITAGARH 10.0KM BARASAT KHARDAH (UP 17.88Km) KHARDAH 8.0KM (DN 18.13Km) RISHRA NOAPARA- BARASAT VIA HRIDAYPUR PANIHATI AIRPORT (UP 15.80Km) (DN 16.05Km)BARASAT 6.0KM SODEPUR PROP. NOAPARA- BARASAT KONNAGAR METROMADHYAMGRAM EXTN. AGARPARA (UP 13.35Km) GOBRA 4.5KM (DN 13.60Km) NEW BARRACKPUR HIND MOTOR AGARPARA KAMARHATI BISARPARA NEW BARRACKPUR (UP 10.75Km) 2.5KM (DN 11.00Km) DANKUNI UTTARPARA BARANAGAR BIRATI (UP 7.75Km) PROP.BARANAGAR-BARRACKPORE (DN 8.00Km) BELGHARIA BARRACKPORE/ BELA NAGAR BIRATI DAKSHINESWAR (2.0Km EX.BARANAGAR) BALLY BARANAGAR (0.0Km)(5.2Km EX.DUM DUM) SHANTI NAGAR BIMAN BANDAR 4.55KM (UP 6.15Km) BALLY GHAT RAMKRISHNA PALLI (DN 6.4Km) RAJCHANDRAPUR DAKSHINESWAR 2.5KM DAKSHINESWAR BARANAGAR RD. NOAPARA DAKSHINESWAR - DURGA NAGAR AIRPORT BALLY HALT NOAPARA (0.0Km) (2.09Km EX.DMI) HALDIRAM BARANAGAR BELUR JESSOR RD DUM DUM 5.0KM DUM DUM CANT. CANT 2.60KM NEW TOWN DUM DUM LILUAH KAVI SUBHAS- DUMDUM DUM DUM ROAD CONVENTION CENTER DUM DUM DUM DUM - BELGACHIA KOLKATA DASNAGAR TIKIAPARA AIRPORT BARANAGAR HOWRAH SHYAM BAZAR RAJARHAT RAMRAJATALA SHOBHABAZAR Maidan BIDHAN NAGAR RD. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Here, There, and Elsewhere: A Multicentered Relational Framework for Immigrant Identity Formation Based on Global Geopolitical Contexts Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5817t513 Author Shams, Tahseen Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Here, There, and Elsewhere: A Multicentered Relational Framework for Immigrant Identity Formation Based on Global Geopolitical Contexts A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Tahseen Shams 2018 © Copyright by Tahseen Shams 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Here, There, and Elsewhere: A Multicentered Relational Framework for Immigrant Identity Formation Based on Global Geopolitical Contexts by Tahseen Shams Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Roger Waldinger, Co-Chair Professor Rubén Hernández-León, Co-Chair The scholarship on international migration has long theorized how immigrants form new identities and build communities in the hostland. However, largely limited to studying the dyadic ties between the immigrant-sending and -receiving countries, research thus far has overlooked how sociopolitics in places beyond, but in relation to, the homeland and hostland can also shape immigrants’ identities. This dissertation addresses this gap by introducing a more comprehensive analytical design—the multicentered relational framework—that encompasses global political contexts in the immigrants’ homeland, hostland, and “elsewhere.” Based primarily on sixty interviews and a year’s worth of ethnographic data on Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and Indian Muslims in California, I trace how different dimensions of the immigrants’ “Muslim” identity category tie them to different “elsewhere” contexts. -

'Spaces of Exception: Statelessness and the Experience of Prejudice'

London School of Economics and Political Science HISTORIES OF DISPLACEMENT AND THE CREATION OF POLITICAL SPACE: ‘STATELESSNESS’ AND CITIZENSHIP IN BANGLADESH Victoria Redclift Submitted to the Department of Sociology, LSE, for the degree of PhD, London, July 2011. Victoria Redclift 21/03/2012 For Pappu 2 Victoria Redclift 21/03/2012 Declaration I confirm that the following thesis, presented for examination for the degree of PhD at the London School of Economics and Political Science, is entirely my own work, other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. ____________________ ____________________ Victoria Redclift Date 3 Victoria Redclift 21/03/2012 Abstract In May 2008, at the High Court of Bangladesh, a ‘community’ that has been ‘stateless’ for over thirty five years were finally granted citizenship. Empirical research with this ‘community’ as it negotiates the lines drawn between legal status and statelessness captures an important historical moment. It represents a critical evaluation of the way ‘political space’ is contested at the local level and what this reveals about the nature and boundaries of citizenship. The thesis argues that in certain transition states the construction and contestation of citizenship is more complicated than often discussed. The ‘crafting’ of citizenship since the colonial period has left an indelible mark, and in the specificity of Bangladesh’s historical imagination, access to, and understandings of, citizenship are socially and spatially produced. -

Community, Nation and Politics in Colonial Bihar (1920-47)

www.ijcrt.org © 2020 IJCRT | Volume 8, Issue 10 October 2020 | ISSN: 2320-2882 COMMUNITY, NATION AND POLITICS IN COLONIAL BIHAR (1920-47) Md Masoom Alam, PhD, JNU Abstract The paper is an attempt to explore, primarily, the nationalist Muslims and their activities in Bihar, since 1937 till 1947. The work, by and large, will discuss the Muslim personalities and institutions which were essentially against the Muslim League and its ideology. This paper will be elaborating many issues related to the Muslims of Bihar during 1920s, 1930s and 1940s such as the Muslim organizations’ and personalities’ fight for the nation and against the League, their contribution in bridging the gulf between Hindus and Muslims and bringing communal harmony in Bihar and others. Moreover, apart from this, the paper will be focusing upon the three core issues of the era, the 1946 elections, the growth of communalism and the exodus of the Bihari Muslims to Dhaka following the elections. The paper seems quite interesting in terms of exploring some of the less or underexplored themes and sub-themes on colonial Bihar and will certainly be a great contribution to the academia. Therefore, surely, it will get its due attention as other provinces of colonial India such as U. P., Bengal, and Punjab. Introduction Most of the writings on India’s partition are mainly focused on the three provinces of British India namely Punjab, Bengal and U. P. Based on these provinces, the writings on the idea of partition and separatism has been generalized with the misperception that partition was essentially a Muslim affair rather a Muslim League affair. -

Education Policy in West Bengal

Education Policy In West Bengal meekly.Sometimes How uncomfortable lax is Francis Daviswhen misappropriateswiggly and infusive her Simone ranking avoidunknightly, some butpolemarch? bistred Boris mothers illegally or hypostatised soaringly. Rad overcome Boys dropped and development of hindu state govemment has been prescribed time, varshiki and west in urban areas contract teachers and secondary schools The policy research methodology will be? How effectively utilize kyan has been set up to west bengal indicate that would support in education policy west bengal? Huq was not in west in bengal education policy, which were zamindars as a perfect crime reporter in. To achieve gender norms and. After a voluntary organisations were built by employing ict. The new leaders dominated western sciences are often takes drugs? Textbooks were dedicated to icse and. Candidates each other. This chapter will help many of education policy? Maulvi syed ahmed also seek different legislative framework. This background to wash their islamic culture of schools but hindus for studies will be cleared without persian. West bengal government wanted muslim. Muslim inspectors are involved with parents, private schools has not really sufficient progress as fazlul huq was highest academic year plan period financial. There is of west bengal proposed by hindu consciousness among muslims education policy in west bengal and. Initially muslim students from lower classes with other stationeries, by japanese bombs followed. As to maintain their capability enhancement with an urgent issue as fees, separate nation one primary level for? Prime objective of policies were not enrolled into limelight once all. The policies were still taken into professional training facility to continue securing grants. -

The Taj: an Architectural Marvel Or an Epitome of Love?

Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 7(9): 367-374, 2013 ISSN 1991-8178 The Taj: An Architectural Marvel or an Epitome of Love? Arshad Islam Head, Department of History & Civilization, International Islamic University Malaysia Abstract: On Saturday 7th July 2007, the New Seven Wonders Foundation, Switzerland, in its new ranking, again declared the Taj Mahal to be one of the Seven Wonders of the World. The Taj Mahal is not just an architectural feat and an icon of luminous splendour, but an epitome of enormous love as well. The Mughal Emperor Shahjahan (1592-1666) built the Taj Mahal, the fabulous mausoleum (rauza), in memory of his beloved queen Mumtaz Mahal (1593-1631). There is perhaps no better and grander monument built in the history of human civilization dedicated to love. The contemporary Mughal sources refer to this marvel as rauza-i-munavvara (‘the illumined tomb’); the Taj Mahal of Agra was originally called Taj Bibi-ka-Rauza. It is believed that the name ‘Taj Mahal’ has been derived from the name of Mumtaz Mahal (‘Crown Palace’). The pristine purity of the white marble, the exquisite ornamentation, use of precious gemstones and its picturesque location all make Taj Mahal a marvel of art. Standing majestically at the southern bank on the River Yamuna, it is synonymous with love and beauty. This paper highlights the architectural design and beauty of the Taj, and Shahjahan’s dedicated love for his beloved wife that led to its construction. Key words: INTRODUCTION It is universally acknowledged that the Taj Mahal is an architectural marvel; no one disputes it position as one of the Seven Wonders of the World, and it is certainly the most fêted example of the considerable feats of Mughal architecture. -

Citizens of Nowhere

A POWERFUL VOICE FOR LIFESAVING ACTION ciTizens of nowhere The STaTeless BihariS of BangladeSh Maureen Lynch & ThaTcher cook To The reader Millions of people in the world are citizens of nowhere. They can- not vote. They cannot get jobs in most professions. They cannot own property or obtain a passport. These “stateless” people frequently face discrimination, harassment, violence, and severe socioeconomic hardship. due to their status, they are often denied access to even the most basic healthcare and education that is available to citizens in the same country. The Biharis of Bangladesh are one such stateless population. Ban- gladesh has hosted 240,000–300,000 Biharis (also called stranded Pakistanis) since the civil war between east and West Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh in 1971. neither Pakistan nor Bangla- desh claims Biharis as citizens. in november 2004, refugees international visited 11 Bihari camps in Bangladesh. We now invite you to learn more about their situation and to help restore the rights of these stateless individuals. We would like to offer special thanks to each individual who willingly and courageously told us their stories. Much apprecia- tion is due everyone who provided support for the original field visit on which this project is based and who helped in the production of this photo report. Maureen lynch and Thatcher Cook refugees international The photographs for further information in this report lives on hold: The human Cost of Statelessness, were taken by a Refugees International publication available online at: Thatcher Cook. http://www.refintl.org/content/issue/detail/5051 thatcher@ thatchercook.com fifty Years in limbo: The Plight of the World’s Stateless People, a Refugees International publication available online at: http://www.refintl.org/content/article/detail/915 JANUARY 2006 Citizens of nowhere: the stateless Biharis of Bangladesh Table of ConTenTs The human Cost of Statelessness ....................... -

State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance Among the Santal in Bangladesh

The Issue of Identity: State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance among the Santal in Bangladesh PhD Dissertation to attain the title of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Submitted to the Faculty of Philosophische Fakultät I: Sozialwissenschaften und historische Kulturwissenschaften Institut für Ethnologie und Philosophie Seminar für Ethnologie Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg This thesis presented and defended in public on 21 January 2020 at 13.00 hours By Farhat Jahan February 2020 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Reviewers: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Assessment Committee: Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Prof. Dr. Kirsten Endres Prof. Dr. Rahul Peter Das To my parents Noor Afshan Khatoon and Ghulam Hossain Siddiqui Who transitioned from this earth but taught me to find treasure in the trivial matters of life. Abstract The aim of this thesis is to trace transformations among the Santal of Bangladesh. To scrutinize these transformations, the hegemonic power exercised over the Santal and their struggle to construct a Santal identity are comprehensively examined in this thesis. The research locations were multi-sited and employed qualitative methodology based on fifteen months of ethnographic research in 2014 and 2015 among the Santal, one of the indigenous groups living in the plains of north-west Bangladesh. To speculate over the transitions among the Santal, this thesis investigates the impact of external forces upon them, which includes the epochal events of colonization and decolonization, and profound correlated effects from evangelization or proselytization. The later emergence of the nationalist state of Bangladesh contained a legacy of hegemony allowing the Santal to continue to be dominated. -

In East Pakistan (1947-71)

Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh (Hum.), Vol. 63(1), 2018, pp. 59-89 THE INVISIBLE REFUGEES: MUSLIM ‘RETURNEES’ IN EAST PAKISTAN (1947-71) Anindita Ghoshal* Abstract Partition of India displaced huge population in newly created two states who sought refuge in the state where their co - religionists were in a majority. Although much has been written about the Hindu refugees to India, very less is known about the Muslim refugees to Pakistan. This article is about the Muslim ‘returnees’ and their struggle to settle in East Pakistan, the hazards and discriminations they faced and policy of the new state of Pakistan in accommodating them. It shows how the dream of homecoming turned into disillusionment for them. By incorporating diverse source materials, this article investigates how, despite belonging to the same religion, the returnee refugees had confronted issues of differences on the basis of language, culture and region in a country, which was established on the basis of one Islamic identity. It discusses the process in which from a space that displaced huge Hindu population soon emerged as a ‘gradual refugee absorbent space’. It studies new policies for the rehabilitation of the refugees, regulations and laws that were passed, the emergence of the concept of enemy property and the grabbing spree of property left behind by Hindu migrants. Lastly, it discusses the politics over the so- called Muhajirs and their final fate, which has not been settled even after seventy years of Partition. This article intends to argue that the identity of the refugees was thus ‘multi-layered’ even in case of the Muslim returnees, and interrogates the general perception of refugees as a ‘monolithic community’ in South Asia.