A Sociological Study of Street Children in Howrah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memo 2018 2018 1 Index

memo MEMO 2018 2018 1 INDEX WHO WE ARE Acknowledgement Letter 3 Our History 4 Where we Work: Pilkhana, The City of Joy” 5 Mission, Vision, Values and Principles 6 Colores de Calcuta Community 8 COOPERATION FOR DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Services 12 Beneficiaries 2018 14 Pilkhana Medical Centre 16 Medical Services 17 Economic Benefits 19 Hospital Accompaniment 19 Health Awareness Workshops 20 Collaboration with Public Health Programmes 20 Child Units: 24 Child Nutrition Programme 24 Nursery School 27 Anand Bhavan 30 Home for girls and teenage girls 30 Scholarship Programme and accompaniment to achieving an independent life 36 Women Artisans Group 37 AWARENESS RAISING AND VOLUNTEERING PROGRAMME FUNDRAISING AND COMMUNICATION Solidarity Events and Initiatives 40 Communication and Media 43 Collaborating Entities 44 TRANSPARENCY Origin and Use of Resources 46 2 COLORES DE CALCUTA FOUNDATION THANK YOU Dear friends, In this memo, we share the work carried out during 2018. A year in which the team made up of Colores de Calcuta Foundation and our counterpart Seva Sangh Samity has gained strength. A year in which our centres in Kolkata, the Medical Centre and Anand Bhavan, have continued to grow and consolidate their services. A year in which we have grown in our care capabilities, accompanying more than 27,000 beneficiaries in order to improve their quality of life. A year in which we have done a thorough analysis of our working model: a humanistic model of opportunities, capabilities and rights, focusing on people. All this has been possible thanks to all the people who work, participate, collaborate and make up theColores de Calcuta Community. -

Metro Railway Kolkata Presentation for Advisory Board of Metro Railways on 29.6.2012

METRO RAILWAY KOLKATA PRESENTATION FOR ADVISORY BOARD OF METRO RAILWAYS ON 29.6.2012 J.K. Verma Chief Engineer 8/1/2012 1 Initial Survey for MTP by French Metro in 1949. Dum Dum – Tollygunge RTS project sanctioned in June, 1972. Foundation stone laid by Smt. Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India on December 29, 1972. First train rolled out from Esplanade to Bhawanipur (4 km) on 24th October, 1984. Total corridor under operation: 25.1 km Total extension projects under execution: 89 km. June 29, 2012 2 June 29, 2012 3 SEORAPFULI BARRACKPUR 12.5KM SHRIRAMPUR Metro Projects In Kolkata BARRACKPUR TITAGARH TITAGARH 10.0KM BARASAT KHARDAH (UP 17.88Km) KHARDAH 8.0KM (DN 18.13Km) RISHRA NOAPARA- BARASAT VIA HRIDAYPUR PANIHATI AIRPORT (UP 15.80Km) (DN 16.05Km)BARASAT 6.0KM SODEPUR PROP. NOAPARA- BARASAT KONNAGAR METROMADHYAMGRAM EXTN. AGARPARA (UP 13.35Km) GOBRA 4.5KM (DN 13.60Km) NEW BARRACKPUR HIND MOTOR AGARPARA KAMARHATI BISARPARA NEW BARRACKPUR (UP 10.75Km) 2.5KM (DN 11.00Km) DANKUNI UTTARPARA BARANAGAR BIRATI (UP 7.75Km) PROP.BARANAGAR-BARRACKPORE (DN 8.00Km) BELGHARIA BARRACKPORE/ BELA NAGAR BIRATI DAKSHINESWAR (2.0Km EX.BARANAGAR) BALLY BARANAGAR (0.0Km)(5.2Km EX.DUM DUM) SHANTI NAGAR BIMAN BANDAR 4.55KM (UP 6.15Km) BALLY GHAT RAMKRISHNA PALLI (DN 6.4Km) RAJCHANDRAPUR DAKSHINESWAR 2.5KM DAKSHINESWAR BARANAGAR RD. NOAPARA DAKSHINESWAR - DURGA NAGAR AIRPORT BALLY HALT NOAPARA (0.0Km) (2.09Km EX.DMI) HALDIRAM BARANAGAR BELUR JESSOR RD DUM DUM 5.0KM DUM DUM CANT. CANT 2.60KM NEW TOWN DUM DUM LILUAH KAVI SUBHAS- DUMDUM DUM DUM ROAD CONVENTION CENTER DUM DUM DUM DUM - BELGACHIA KOLKATA DASNAGAR TIKIAPARA AIRPORT BARANAGAR HOWRAH SHYAM BAZAR RAJARHAT RAMRAJATALA SHOBHABAZAR Maidan BIDHAN NAGAR RD. -

Kolkata Stretcar Track

to BANDEL JN. and DANKUNI JN. to NAIHATI JN. to BARASAT JN. Kolkata 22./23.10.2004 M DUM DUM Streetcar track map: driving is on the left r in operation / with own right-of-way the second track from the right tracks seeming to be operable e is used to make the turns of the regular passenger trains track trunks which are not operable v other routes in 1996 according to Tasker i other suspended routes according to CTC map TALA 11 [13] R actual / former route number according to CTC ULTADANGA ROAD Suburban trains and ‘Circular Railway’ according to Narayanan: Galif [12] i BELGATCHIA in operation under construction l Street [13] 1 2 11 PATIPUKUR A.P.C. Rd[ 20 ] M Note: The route along the Hugly River can’t be confirmed by my own g 12 Belgatchia observations. Bagbazar SHYAM BAZAR R.G. Kar Rd u BAG BAZAR M M metro railway pb pedestrian bridge 1 2 [4] 11 H Shyambazar BIDHAN NAGAR ROAD pb TIKIAPARA [8] 5 SOVA SOVA BAZAR – M BAZAR 6 AHIRITOLA Bidhan Nagar to PANSKURA JN. Aurobinda Sarani 17 housing block [4] 20 20 [12] [13] [ 12 ] 17 loop Esplanade [10] Rabindra Setu Nimtala enlargement (Howrah Bridge) pb [4] 1 [8] GIRISH 2 Howrah [10] M PARK 5 BURRA 6 15 Bidhan Sarani Rabindra Sarani 11 BAZAR 11 12 20 [21] [26] V.I.P. Rd 15 HOWRAH 11 12 M.G. 30Rd MAHATMA Maniktala Main Rd RAILWAY GANDHI 20 30 Acharya Profullya Chandra Rd STATION M ROAD M.G. Rd 20 Howrah [16] 17 17 Northbound routes are [12] [13] [16] M turning counterclockwise, Bridge 15 Mahatma Gandhi Rd 20 20 southbound routes are [4] 11 12 15 17 [ 12 ] 17 ESPLANADE 12 20 turning clockwise. -

Speech of Mamata Banerjee Introducing the Railway Budget 2011-12 25Th February 2011

Speech of Mamata Banerjee introducing the Railway Budget 2011-12 25th February 2011 1. Madam Speaker, I rise to present before this august House the Revised Estimates for 2010-11 and the estimated receipts and expenditure for 2011-12. I deem it an honour to present the third Railway Budget under the kind guidance of the hon'ble Prime Minister. I profusely thank the Finance Minster for his continued support and encouragement to the railways. 2. As the hon’ble members are aware, the wheels of the railways continue to move 24 hours, all 365 days. Railway’s services are comparable to emergency services, required all the time. I am proud of the 14 lakh members of my railway family, who toil day and night with unparalleled dedication. I am also grateful to all passengers without whose cooperation and consideration, we could not have run this vast system. I have also received unstinted support from our two recognised federations and staff and officers’ associations. 3. Madam, rail transportation is vitally interlinked with the economic development of the country. With the economy slated to grow at a rate of 8-9%, it is imperative that the railways grow at an even faster pace. I see the railways as an artery of this pulsating nation. Our lines touch the lives of humble people in tiny villages, as they touch the lives of those in the bustling metropolises. 4. We are taking a two-pronged approach, scripted on the one hand, by a sustainable, efficient and rapidly growing Indian Railways, and on the other, by an acute sense of social responsibility towards the common people of this nation. -

Good Stories Under Howrah Police Commissionerate As on 10.04.2017 Any Other Sl

Good Stories under Howrah Police Commissionerate as on 10.04.2017 Any other Sl. Case details (Gist) with section Details report of Investigation Any recovery / detection important No. information Howrah P.S. Case No. 772/16 dtd.- 19/12/16 U/S- 379 I.P.C. On 18.12.16 in between Stolen Motor Cycle has been recovered Recovered the stolen Motor Cycle being no. WB-38AD/5309. 22:30 hrs. to 05:00 hrs unknown miscreant stolen away complainant’s Black colour Bajaj Pulsar 150 CC motorcycle, having Reg. No. WB/38AD-5309, Chassis No. 1 MDZA11CZ3ECCO9642, Engine No. MHZCEC87894 which was parked in front of his friend’s house at 129/1 Noor Mahammed Musnhi Lane, PS & Dist. Howrah. Howrah P.S. Case No. 108/17 dtd.- 25/02/17 U/S- 25(1B)(a)/29/35 Arms Act. On Two accused persons have been arrested. Recovered 1 country made improvised fire arms and 02 ammunitions. 25.02.17 at 00:05 source information that one Samshad Alam and another Raja of Tikiapara will hand over a consignment of arms and ammunition to one Anwar of Jagaddal accordingly the complainant along with others left from PS to work-out the information at reached towards Railway Museum Southern side and found one motorcycle came from Telkolghat side in a very high speed and the rider was wearing a 2 full covered helmet and stopped in front of the targeted person and started talking with them. But after a hot chase we able to detained one of the person who is carrying a shopping bag in his right hand grip. -

Chapter II METHODOLOGY, STUDY AREA and the POPULATION

Chapter II METHODOLOGY, STUDY AREA AND THE POPULATION Chapter II METHODOLOGY, STUDY AREA AND THE POPULATION This study is exploratory in nature. It makes an attempt to understand the life of the street children living in Howrah railway station and its adjoining areas of West Bengal. Particularly the Howrah station and its surroundings, within the jurisdiction of ward No 19 of Howrah Municipal Corporation (HMC), is the place which had been selected for the purpose of present study. A large number of street children is always found in and around the Howrah station premises like Howrah bustand, Martin bridge slum, Sabji (Vegitable) Market, Ganga ghat area and Rail museum etc. On and average around 170 to 180 street children are found around this place of which 75 were selected as informants for in depth interview. They were selected randomly from different platforms of Howrah station and from its adjoining areas. They were interviewed with an interview schedule. The sample survey was conducted on the street children belonging to the age group between 6 to 15 years. Method of Data Collection At the outset a census schedule was administered to make a quick enumeration of the street children living in the study area with an aim to get an idea about their socio-economic back ground in general. Secondly in the present study, an interview schedule, especially designed for the street children, was used for data collection. The sampled respondents were interviewed personally in view of following reasons. 1. Respondents were mostly illiterate. So they were needed to approach individually and to record their answers properly. -

Eastern Railway Divisional Railway Manager's Office, Howrah OPEN

Eastern Railway Divisional Railway Manager’s Office, Howrah OPEN TENDER NOTICE Tender Notice No. MC/2/S/Blanket/Rep/IV dated 03.11.2015 Blanket repairing by flap stitching of edges and ‘IR’ embroidery marking as per specimen at Tikiapara and Sorting Yard Coaching 1. Name of work with location : Complex of Howrah Division for a period of 3 years under CDO/TKPR Rs.20,05,265/- (Rupees twenty lakh five thousand two hundred 2. Tender value : sixty five) only 3. Earnest Money to be deposited : Rs.40,110/- (Rupees forty thousand one hundred ten) only 4. Cost of Tender Document : Rs.3,000/- (Rupees three thousand) only Office of the Senior Divisional Mechanical Engineer (C&W), Address of the Office from where the 5. : Howrah at Divisional Railway Manager’s Office, Eastern Railway, Tender Document can be obtained Howrah (beside Howrah Station), PIN – 711101. On all working days from 24.11.2015 to 14.12.2015 between 11:00 6. Date of obtaining Tender Document : hrs and 18:00 hrs. From 04.12.2015 to 14.12.2015 between 11:00 hrs and 18:00 hrs 6. Period for submission of Tender : on all working days and on 15.12.2015 up to 14:00 hrs. 7. Date and Time for opening of Tender : 15.12.2015 at 15:00 hrs. Website Particulars where complete 8. : www.er.indianrailways.gov.in details of Tender can be downloaded Notice Board Location where complete 9. : Notice Board of Rolling Stock Branch at DRM Office, Howrah details of Tender can be seen Sr. -

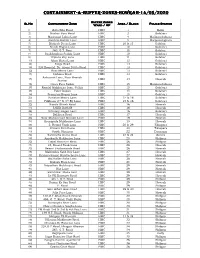

Containment-&-Buffer-Zones

CONTACONTAINMENTINMENTINMENT----&&&&----BUFFERBUFFERBUFFER----ZONESZONESZONES----HOWRAHHOWRAHHOWRAH----10101010/05//05//05/20202020 BUFFER ZONES SL NO CONTAINMENT ZONE AREA /// BLOCK POLICE STATION WARD /// GPGPGP 1) Matrumal Lohia Lane HMC 4 Malipanchghara 2) Sombhu Halder Lane HMC 5 Malipanchghara 3) Bhairab Dutta Lane HMC 10 & 15 Golabari 4) Nandi Bagan Lane HMC 10 Golabari 5) 360, G.T. R oad HMC 10 Golabari 6) Atul Ghosh Lane HMC 12 Golabari 7) Alam Mistri Lane HMC 13 Golabari 8) Kings Road HMC 13 Golabari 9) ILS Hospital, Dr. Abani Dutta Road HMC 13 Golabari 10) Rose Merry Lane HMC 13 Golabari 11) Ashutosh Lane, Near Howrah Station HMC 14 Howrah 12) Oriya Para Salkia HMC 15 Malipanchghara 13) Kapoor Galli HMC 15 Golabari 14) Ramlal Mukherjee lane, Salkia HMC 15 Golabari 15) Fakir Bagan HMC 15 Golabari 16) Sanatan Mistry Lane HMC 15 & 16 Golabari 17) Pilkhana 2 nd & 3 rd By Lane HMC 15 & 16 Golabari 18) Nanda Ghosh Road HMC 16 Howrah 19) Fakir Bagan HMC 16 Howrah 20) Srimony Bagan Lane HMC 16 Golabari 21) Belilious Road HMC 17 Howrah 22) Laxman Das Lane HMC 18 Howrah 23) District Hospital premises Hqts HMC 19 Howrah 24) Noor Muhammad Munsh i Lane HMC 19 Howrah 25) Gauripada Mukherjee Lane HMC 19 Howrah 26) Basiruddin Munshi Lane HMC 19 & 20 Howrah 27) Jolapara Masjid Lane HMC 19, 20 & 42 Howrah 28) 2, Round Tank Lane HMC 20 Tikiapara 29) South Shanpur HMC 22 Dasnagar 30) Narsingha Dutta Road HMC 23 & 24 Bantra 31) Jaynarayan Babu Ananda Dutta Lane HMC 24 Bantra 32) Aprokadh Mukherjee Lane HMC 25 Shibpur 33) Baishnab Para Lane HMC 26 Howrah 34) Dayal Banerjee Road HMC 26 Shibpur 35) 15, Round Tank Lane HMC 26 Howrah 36) Mahendra Nath Roy Lane HMC 27 Howrah 37) Jogmaya Devi Lane HMC 27 Howrah 38) Krishna Kamal Bhattacharya Lane HMC 27 Howrah 39) Raj Ballav Saha Lane HMC 28 Howrah 40) Nityadhan Mukherjee Road HMC 29 Howrah 41) Hat Lane HMC 29 Howrah 42) Rameswar Maliya Lane HMC 29 Howrah 43) Dr PK Banerjee Road HMC 29 Howrah 44) 48/1, G.T. -

8.1.1 ¢ [ रेल े South Eastern Railway

8.1.1 दO>ण पूव रेलवे SOUTH EASTERN RAILWAY 20192019----2020 के िलए पƗरसंपिēयĪ कƙ खरीद , िनमाϕण और बदलाव Assets-Acquisition, Construction and Replacement for 2019-20 (Figures in thousand of Rupees)(आंकड़े हजार Đ . मĞ) पूंजी पूंजी िनिध मूआिन िविन संिन रारेसंको जोड़ िववरण Particulars Capital CF DRF. DF SF RRSK TOTAL 11 (a) New Lines (Construction) 6,00 .. .. .. .. .. 6,00 14 G Gauge Conversion 1,01,00 .. .. .. .. .. 1,01,00 15 ह Doubling 50,00 .. .. .. .. .. 50,00 16 - G Traffic Facilities-Yard 44,34,02 .. 5,90 6,79,00 .. 79,52,99 130,71,91 G ^ G Remodelling & Others 17 Computerisation 2,01,00 .. 5,00,00 17,01 .. .. 7,18,01 21 Rolling Stock 7,29,51 .. .. .. .. 18,32,95 25,62,46 22 * 4 - Leased Assets - Payment 583,19,70 231,50,30 .. .. .. .. 814,70,00 of Capital Component 29 E G - Road Safety Works-Level .. .. .. .. .. 61,84,08 61,84,08 Crossings. 30 E G -/ Road Safety Works-Road .. .. .. .. .. 177,61,00 177,61,00 Over/Under Bridges. 31 Track Renewals .. .. .. .. .. 658,05,01 658,05,01 32 G Bridge Works .. .. .. .. .. 44,91,38 44,91,38 33 G Signalling and .. .. .. .. .. 125,95,28 125,95,28 Telecommunication 36 ^ G - G Other Electrical Works 1,39,48 .. 4,46,62 3,76,99 .. 3,38,53 13,01,62 K excl TRD 37 G G Traction Distribution 1,00,99 .. .. .. .. 41,30,18 42,31,17 Works 41 U Machinery & Plant 2,43,54 . -

Howrah City Police Gazette, August 1, 2011

HOWRAH POLICE GAZETTE Government of West Bengal September 2, 2020 Part I Part- II Orders by Commissioner of Police & Deputy Order by the Governor of West Bengal Commissioner of Police, Howrah ORDER Government of West Bengal Office of the Commissioner of Police Government of West Bengal Howrah Home & Hill Affairs Department Police Service Cell ORDER Block-IV, 1st Floor, Writers’ Buildings Kolkata – 700 001. CO No. 1900 Dated : 17.08.2020 No. 681-P.S. Cell/HR/O/3P-10/17 Date : 13.08.2020 Shri Krishnendu Mondal, Inspector of Police, HPC is posted as Inspector, Control Room, Howrah Police Commissionerate and he NOTIFICATION will also hold the additional charge of OC, Licence Section, HPC until further order. The Governor is pleased to appoint the following Inspectors of Police (Armed Branch) to the rank of Deputy Superintendent of Sd./- Police (Armed Branch) with place of posting as noted against each, Commissioner of Police on promotion, with usual pay and allowances in terms of the West Howrah. Bengal Service (ROPA) Rules, 2019, i.e. (Rs. 56,100/- - Rs. 1,44,300/) Level 16 (“Pay Matrix Level”) with effect from the date/s of their assuming charges and until further orders:- Place of Sl. Name of the Present Place of posting Posting on No. officers Government of West Bengal promotion Office of the Commissioner of Police IC 2nd Hooghly Bridge, Atunu Howrah 14. Howrah Police AC, PTS, Salua Banerjee Commissionerate ORDER TI (HQ), Md. Abid AC, RAF Bn., 16. Howrah Police Hossain Durgapur CO No. 1977 Dated : 26.08.2020 Commissionerate During the quarantine period of OC, Bally PS, Howrah PC, These appointments are made in the interest of public service. -

Containment-&-Buffer-Zones

CONTACONTAINMENTINMENTINMENT----&&&&----BUFFERBUFFERBUFFER----ZONESZONESZONES----HOWRAHHOWRAHHOWRAH----14141414/05//05//05/20202020 Buffer Zones SlSlSl NoNoNo Containment Zone Area /// Block Police Station Ward /// GPGPGP 1) Zaya Bibi Road HMC 1 Belur 2) Naskar Para Road HMC 2 Golabari 3) Matrumal Lohia Lane HMC 4 Malipanchghara 4) Sombhu Halder Lane HMC 5 Malipanchghara 5) Bhairab Dutta Lane HMC 10 & 15 Golabari 6) Nandi Bagan Lane HMC 10 Golabari 7) 360, G.T. Road HMC 10 Golabari 8) Sasibhushan Sarkar Lane HMC 10 Golabari 9) Tripura Roy Lane HMC 11 Golabari 10) Alam Mistri Lane HMC 13 Golabari 11) Kings Road HMC 13 Golabari 12) ILS Hospital, Dr. Abani Dutta Road HMC 13 Golabari 13) Rose Merry Lane HMC 13 Golabari 14) Dobson Road HMC 13 Golabari Ashutosh Lane, Near Howrah 15) HMC 14 Howrah Station 16) Oriya Para Salkia HMC 15 Malipanchghara 17) Ramlal Mukherjee lane, Salkia HMC 15 Golabari 18) Fakir Bagan HMC 15 Golabari 19) Sreemani Bagan Lane HMC 15 Golabari 20) Sanatan Mistry Lane HMC 15 & 16 Golabari 21) Pilkhana 2 nd & 3 rd By Lane HMC 15 & 16 Golabari 22) Nanda Ghosh Road HMC 16 Howrah 23) FAKIR BAGAN HMC 16 Howrah 24) Srimony Bagan Lane HMC 16 Golabari 25) Belilious Road HMC 17 Howrah 26) Noor Muhammad Munshi Lane HMC 19 Howrah 27) Ga uripada Mukherjee Lane HMC 19 Howrah 28) 2, Round Tank Lane HMC 20 & 29 Tikiapara 29) Srinath Porel Lane HMC 20 Tikiapara 30) South Shanpur HMC 22 Dasnagar 31) Narsingha Dutta Road HMC 23 & 24 Bantra 32) Aprokadh Mukherjee Lane HMC 25 Shibpur 33) Dayal Banerjee Road HMC 26 Shibpur 34) 15, Round Tank Lane HMC 26 Howrah 35) Swami Vivekananda Road HMC 26 Howrah 36) Mahendra Nath Roy Lane HMC 27 Howrah 37) Krishna Kamal Bhattacharya Lane HMC 27 Howrah 38) Raj Ballav Saha Lane HMC 28 Howrah 39) Kailash Bose Lane HMC 28 Howrah 40) Nityadhan Mukherjee Road HMC 29 Howrah 41) Hat Lane HMC 29 Howrah 42) Rameswar Malia Lane HMC 29 Howrah 43) Dr PK Banerjee Road HMC 29 Howrah 44) 48/1, G.T. -

Annexure – 3 & 4 Sl. No. Particulars Year Amount (Rs.) 1 Supply and Installation of High Mast Light at Tikiapara, Howrah

Annexure – 3 & 4 Sl. Particulars Year Amount No. (Rs.) 1 Supply and Installation of High Mast Light at Tikiapara, Howrah 2015-16 4,98,871.00 2 4 nos. of Grill installation at PMY,Khalore, Bagnan -Do- 1,64,074.00 3 Construction of Sufal Bangla Market Herb at Mandirtala, Howrah -Do- 2,77,793.00 4 Construction for improvement of Market Link Road at -Do- 18,20,969.00 DihibhushutDakshin Primary School towards Ghola Primary School, Dihibhushut, Howrah 5 Installation of 29 LED Street Light at different area under 178 Uluberua -Do- 2,61,053.00 AC, Ulubeira, Howrah 6 Improvement of market Link Road at House of Mohan mallick lane -Do- 20,53,578.00 towards GargBhawanipur market, GarhBhawanipur, Howrah 7 Construction for improvement of Market Link Road from Tulsiberia -Do- 22,54,095.00 Bazar to Tulsiberia West Primary School under Tulsiberia GP, Howrah 8 Sinking of 5 nos. of Tube Well under 178 Uluberia AC area, Uluberia, -Do- 4,60,037.00 Howrah 9 Improvement of Concrete Market Link Road at Bhutnath Mukherjee -Do- 4,44,641.00 Road and repairing of Drain with Dustbin located at ward no. 33 under HMC, Howrah 10 Installation of 22 Nos. street LightatAbinash Banerjee Lane Ward no. 33 -Do- 3,44,671.00 under HMC, Howrah 11 Construction of Market Link Road at Anantadeb Mukherjee Lane from -Do- 3,37,266.00 2/5/8 to 2/5/12 located at ward no 33, Central Howrah under HMC, Howrah 12 Construction for improvement of Market Link Road at Kestra Banerjee -Do- 2,24,062.00 Lane from 90/2/1 to 39/9 located at Ward No.