In East Pakistan (1947-71)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birth of Bangladesh: Down Memory Lane

Indian Foreign Affairs Journal Vol. 4, No. 3, July - September, 2009, 102-117 ORAL HISTORY Birth of Bangladesh: Down Memory Lane Arundhati Ghose, often acclaimed for espousing wittily India’s nuclear non- proliferation policy, narrates the events associated with an assignment during her early diplomatic career that culminated in the birth of a nation – Bangladesh. Indian Foreign Affairs Journal (IFAJ): Thank you, Ambassador, for agreeing to share your involvement and experiences on such an important event of world history. How do you view the entire episode, which is almost four decades old now? Arundhati Ghose (AG): It was a long time ago, and my memory of that time is a patchwork of incidents and impressions. In my recollection, it was like a wave. There was a lot of popular support in India for Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his fight for the rights of the Bengalis of East Pakistan, fund-raising and so on. It was also a difficult period. The territory of what is now Bangladesh, was undergoing a kind of partition for the third time: the partition of Bengal in 1905, the partition of British India into India and Pakistan and now the partition of Pakistan. Though there are some writings on the last event, I feel that not enough research has been done in India on that. IFAJ: From India’s point of view, would you attribute the successful outcome of this event mainly to the military campaign or to diplomacy, or to the insights of the political leadership? AG: I would say it was all of these. -

'Spaces of Exception: Statelessness and the Experience of Prejudice'

London School of Economics and Political Science HISTORIES OF DISPLACEMENT AND THE CREATION OF POLITICAL SPACE: ‘STATELESSNESS’ AND CITIZENSHIP IN BANGLADESH Victoria Redclift Submitted to the Department of Sociology, LSE, for the degree of PhD, London, July 2011. Victoria Redclift 21/03/2012 For Pappu 2 Victoria Redclift 21/03/2012 Declaration I confirm that the following thesis, presented for examination for the degree of PhD at the London School of Economics and Political Science, is entirely my own work, other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. ____________________ ____________________ Victoria Redclift Date 3 Victoria Redclift 21/03/2012 Abstract In May 2008, at the High Court of Bangladesh, a ‘community’ that has been ‘stateless’ for over thirty five years were finally granted citizenship. Empirical research with this ‘community’ as it negotiates the lines drawn between legal status and statelessness captures an important historical moment. It represents a critical evaluation of the way ‘political space’ is contested at the local level and what this reveals about the nature and boundaries of citizenship. The thesis argues that in certain transition states the construction and contestation of citizenship is more complicated than often discussed. The ‘crafting’ of citizenship since the colonial period has left an indelible mark, and in the specificity of Bangladesh’s historical imagination, access to, and understandings of, citizenship are socially and spatially produced. -

Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions Poster Sessions Continuing

Sessions and Events Day Thursday, January 21 (Sessions 1001 - 1025, 1467) Friday, January 22 (Sessions 1026 - 1049) Monday, January 25 (Sessions 1050 - 1061, 1063 - 1141) Wednesday, January 27 (Sessions 1062, 1171, 1255 - 1339) Tuesday, January 26 (Sessions 1142 - 1170, 1172 - 1254) Thursday, January 28 (Sessions 1340 - 1419) Friday, January 29 (Sessions 1420 - 1466) Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions More than 50 sessions and workshops will focus on the spotlight theme for the 2019 Annual Meeting: Transportation for a Smart, Sustainable, and Equitable Future . In addition, more than 170 sessions and workshops will look at one or more of the following hot topics identified by the TRB Executive Committee: Transformational Technologies: New technologies that have the potential to transform transportation as we know it. Resilience and Sustainability: How transportation agencies operate and manage systems that are economically stable, equitable to all users, and operated safely and securely during daily and disruptive events. Transportation and Public Health: Effects that transportation can have on public health by reducing transportation related casualties, providing easy access to healthcare services, mitigating environmental impacts, and reducing the transmission of communicable diseases. To find sessions on these topics, look for the Spotlight icon and the Hot Topic icon i n the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section beginning on page 37. Poster Sessions Convention Center, Lower Level, Hall A (new location this year) Poster Sessions provide an opportunity to interact with authors in a more personal setting than the conventional lecture. The papers presented in these sessions meet the same review criteria as lectern session presentations. For a complete list of poster sessions, see the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section, beginning on page 37. -

Community, Nation and Politics in Colonial Bihar (1920-47)

www.ijcrt.org © 2020 IJCRT | Volume 8, Issue 10 October 2020 | ISSN: 2320-2882 COMMUNITY, NATION AND POLITICS IN COLONIAL BIHAR (1920-47) Md Masoom Alam, PhD, JNU Abstract The paper is an attempt to explore, primarily, the nationalist Muslims and their activities in Bihar, since 1937 till 1947. The work, by and large, will discuss the Muslim personalities and institutions which were essentially against the Muslim League and its ideology. This paper will be elaborating many issues related to the Muslims of Bihar during 1920s, 1930s and 1940s such as the Muslim organizations’ and personalities’ fight for the nation and against the League, their contribution in bridging the gulf between Hindus and Muslims and bringing communal harmony in Bihar and others. Moreover, apart from this, the paper will be focusing upon the three core issues of the era, the 1946 elections, the growth of communalism and the exodus of the Bihari Muslims to Dhaka following the elections. The paper seems quite interesting in terms of exploring some of the less or underexplored themes and sub-themes on colonial Bihar and will certainly be a great contribution to the academia. Therefore, surely, it will get its due attention as other provinces of colonial India such as U. P., Bengal, and Punjab. Introduction Most of the writings on India’s partition are mainly focused on the three provinces of British India namely Punjab, Bengal and U. P. Based on these provinces, the writings on the idea of partition and separatism has been generalized with the misperception that partition was essentially a Muslim affair rather a Muslim League affair. -

University of Alberta

University of Alberta The Refugee Woman: Partition of Bengal, Women, and the Everyday of the Nation by Paulomi Chakraborty A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English and Film Studies ©Paulomi Chakraborty Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55963-5 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55963-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance Among the Santal in Bangladesh

The Issue of Identity: State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance among the Santal in Bangladesh PhD Dissertation to attain the title of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Submitted to the Faculty of Philosophische Fakultät I: Sozialwissenschaften und historische Kulturwissenschaften Institut für Ethnologie und Philosophie Seminar für Ethnologie Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg This thesis presented and defended in public on 21 January 2020 at 13.00 hours By Farhat Jahan February 2020 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Reviewers: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Assessment Committee: Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Prof. Dr. Kirsten Endres Prof. Dr. Rahul Peter Das To my parents Noor Afshan Khatoon and Ghulam Hossain Siddiqui Who transitioned from this earth but taught me to find treasure in the trivial matters of life. Abstract The aim of this thesis is to trace transformations among the Santal of Bangladesh. To scrutinize these transformations, the hegemonic power exercised over the Santal and their struggle to construct a Santal identity are comprehensively examined in this thesis. The research locations were multi-sited and employed qualitative methodology based on fifteen months of ethnographic research in 2014 and 2015 among the Santal, one of the indigenous groups living in the plains of north-west Bangladesh. To speculate over the transitions among the Santal, this thesis investigates the impact of external forces upon them, which includes the epochal events of colonization and decolonization, and profound correlated effects from evangelization or proselytization. The later emergence of the nationalist state of Bangladesh contained a legacy of hegemony allowing the Santal to continue to be dominated. -

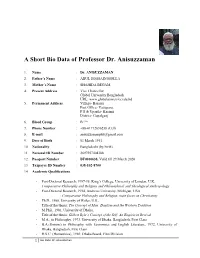

1. Prof. Dr. ANISUZZAMAN

A Short Bio Data of Professor Dr. Anisuzzaman 1. Name : Dr. ANISUZZAMAN 2. Father’s Name : ABUL HOSSAIN MOLLA 3. Mother’s Name : SHAHIDA BEGAM 4. Present Address : Vice Chancellor Global University Bangladesh URL: www.globaluniversity.edu.bd 5. Permanent Address : Village- Barasur Post Office- Vatiapara, P S & Upazila- Kasiani District- Gopalganj 6. Blood Group : B+(ve) 7. Phone Number : +88-01712036238 (Cell) 8. E-mail : [email protected] 9. Date of Birth : 01 March 1951 10. Nationality : Bangladeshi (by birth) 11. National ID Number : 2697557404388 12. Passport Number : BF0010638, Valid till 29 March 2020 13. Taxpayer ID Number : 038-102-8700 14. Academic Qualifications : - Post-Doctoral Research, 1997-98, King’s College, University of London, U.K. Comparative Philosophy and Religion and Philosophical and Theological Anthropology - Post-Doctoral Research, 1994, Andrews University, Michigan, USA : Comparative Philosophy and Religion, main focus on Christianity - Ph.D., 1988, University of Wales, U.K., Title of the thesis: The Concept of Man: Dualism and the Western Tradition - M.Phil., 1981, University of Dhaka, Title of the thesis: Gilbert Ryle’s Concept of the Self: An Empiricist Revival - M.A., in Philosophy, 1973, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh, First Class - B.A.(Honors) in Philosophy with Economics and English Literature, 1972, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh, First Class - H.S.C. (Humanities), 1969, Dhaka Board, First Division 1 Bio Data: Dr. Anisuzzaman - S.S.C., (Humanities), 1967, Dhaka Board, First Division 15. Fields -

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

Report on Citizenship Law:Pakistan

CITIZENSHIP COUNTRY REPORT 2016/13 REPORT ON DECEMBER CITIZENSHIP 2016 LAW:PAKISTAN AUTHORED BY FARYAL NAZIR © Faryal Nazir, 2016 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. EUDO Citizenship Observatory Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies in collaboration with Edinburgh University Law School Report on Citizenship Law: Pakistan RSCAS/EUDO-CIT-CR 2016/13 December 2016 © Faryal Nazir, 2016 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS), created in 1992 and directed by Professor Brigid Laffan, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research on the major issues facing the process of European integration, European societies and Europe’s place in 21st century global politics. The Centre is home to a large post-doctoral programme and hosts major research programmes, projects and data sets, in addition to a range of working groups and ad hoc initiatives. The research agenda is organised around a set of core themes and is continuously evolving, reflecting the changing agenda of European integration, the expanding membership of the European Union, developments in Europe’s neighbourhood and the wider world. -

People Without History

People Without History Seabrook T02250 00 pre 1 24/12/2010 10:45 Seabrook T02250 00 pre 2 24/12/2010 10:45 People Without History India’s Muslim Ghettos Jeremy Seabrook and Imran Ahmed Siddiqui Seabrook T02250 00 pre 3 24/12/2010 10:45 First published 2011 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 www.plutobooks.com Distributed in the United States of America exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 Copyright © Jeremy Seabrook and Imran Ahmed Siddiqui 2011 The right of Jeremy Seabrook and Imran Ahmed Siddiqui to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3114 0 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3113 3 Paperback Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Designed and produced for Pluto Press by Chase Publishing Services Ltd, 33 Livonia Road, Sidmouth, EX10 9JB, England Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed digitally by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, UK and Edwards Bros in the USA Seabrook T02250 00 pre 4 24/12/2010 10:45 Contents Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 1. -

Liberation War of Bangladesh

Bangladesh Liberation War, 1971 By: Alburuj Razzaq Rahman 9th Grade, Metro High School, Columbus, Ohio The Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 was for independence from Pakistan. India and Pakistan got independence from the British rule in 1947. Pakistan was formed for the Muslims and India had a majority of Hindus. Pakistan had two parts, East and West, which were separated by about 1,000 miles. East Pakistan was mainly the eastern part of the province of Bengal. The capital of Pakistan was Karachi in West Pakistan and was moved to Islamabad in 1958. However, due to discrimination in economy and ruling powers against them, the East Pakistanis vigorously protested and declared independence on March 26, 1971 under the leadership of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. But during the year prior to that, to suppress the unrest in East Pakistan, the Pakistani government sent troops to East Pakistan and unleashed a massacre. And thus, the war for liberation commenced. The Reasons for war Both East and West Pakistan remained united because of their religion, Islam. West Pakistan had 97% Muslims and East Pakistanis had 85% Muslims. However, there were several significant reasons that caused the East Pakistani people to fight for their independence. West Pakistan had four provinces: Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan, and the North-West Frontier. The fifth province was East Pakistan. Having control over the provinces, the West used up more resources than the East. Between 1948 and 1960, East Pakistan made 70% of all of Pakistan's exports, while it only received 25% of imported money. In 1948, East Pakistan had 11 fabric mills while the West had nine. -

Dear Aspirant with Regard

DEAR ASPIRANT HERE WE ARE PRESENTING YOU A GENRAL AWERNESS MEGA CAPSULE FOR IBPS PO, SBI ASSOT PO , IBPS ASST AND OTHER FORTHCOMING EXAMS WE HAVE UNDERTAKEN ALL THE POSSIBLE CARE TO MAKE IT ERROR FREE SPECIAL THANKS TO THOSE WHO HAS PUT THEIR TIME TO MAKE THIS HAPPEN A IN ON LIMITED RESOURCE 1. NILOFAR 2. SWETA KHARE 3. ANKITA 4. PALLAVI BONIA 5. AMAR DAS 6. SARATH ANNAMETI 7. MAYANK BANSAL WITH REGARD PANKAJ KUMAR ( Glory At Anycost ) WE WISH YOU A BEST OF LUCK CONTENTS 1 CURRENT RATES 1 2 IMPORTANT DAYS 3 CUPS & TROPHIES 4 4 LIST OF WORLD COUNTRIES & THEIR CAPITAL 5 5 IMPORTANT CURRENCIES 9 6 ABBREVIATIONS IN NEWS 7 LISTS OF NEW UNION COUNCIL OF MINISTERS & PORTFOLIOS 13 8 NEW APPOINTMENTS 13 9 BANK PUNCHLINES 15 10 IMPORTANT POINTS OF UNION BUDGET 2012-14 16 11 BANKING TERMS 19 12 AWARDS 35 13 IMPORTANT BANKING ABBREVIATIONS 42 14 IMPORTANT BANKING TERMINOLOGY 50 15 HIGHLIGHTS OF UNION BUDGET 2014 55 16 FDI LLIMITS 56 17 INDIAS GDP FORCASTS 57 18 INDIAN RANKING IN DIFFERENT INDEXS 57 19 ABOUT : NABARD 58 20 IMPORTANT COMMITTEES IN NEWS 58 21 OSCAR AWARD 2014 59 22 STATES, CAPITAL, GOVERNERS & CHIEF MINISTERS 62 23 IMPORTANT COMMITTEES IN NEWS 62 23 LIST OF IMPORTANT ORGANIZATIONS INDIA & THERE HEAD 65 24 LIST OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS AND HEADS 66 25 FACTS ABOUT CENSUS 2011 66 26 DEFENCE & TECHNOLOGY 67 27 BOOKS & AUTHOURS 69 28 LEADER”S VISITED INIDIA 70 29 OBITUARY 71 30 ORGANISATION AND THERE HEADQUARTERS 72 31 REVOLUTIONS IN AGRICULTURE IN INDIA 72 32 IMPORTANT DAMS IN INDIA 73 33 CLASSICAL DANCES IN INDIA 73 34 NUCLEAR POWER