Antimuslim Racism in Postunification Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20 Dokumentar Stücke Zum Holocaust in Hamburg Von Michael Batz

„Hört damit auf!“ 20 Dokumentar stücke zum Holocaust in „Hört damit auf!“ „Hört damit auf!“ 20 Dokumentar stücke Hamburg Festsaal mit Blick auf Bahnhof, Wald und uns 20 Dokumentar stücke zum zum Holocaust in Hamburg Das Hamburger Polizei- Bataillon 101 in Polen 1942 – 1944 Betr.: Holocaust in Hamburg Ehem. jüd. Eigentum Die Versteigerungen beweglicher jüdischer von Michael Batz von Michael Batz Habe in Hamburg Pempe, Albine und das ewige Leben der Roma und Sinti Oratorium zum Holocaust am fahrenden Volk Spiegel- Herausgegeben grund und der Weg dorthin Zur Geschichte der Alsterdorfer Anstal- von der Hamburgischen ten 1933 – 1945 Hafenrundfahrt zur Erinnerung Der Hamburger Bürgerschaft Hafen 1933 – 1945 Morgen und Abend der Chinesen Das Schicksal der chinesischen Kolonie in Hamburg 1933 – 1944 Der Hannoversche Bahnhof Zur Geschichte des Hamburger Deportationsbahnhofes am Lohseplatz Hamburg Hongkew Die Emigration Hamburger Juden nach Shanghai Es sollte eigentlich ein Musik-Abend sein Die Kulturabende der jüdischen Hausgemeinschaft Bornstraße 16 Bitte nicht wecken Suizide Hamburger Juden am Vorabend der Deporta- tionen Nach Riga Deportation und Ermordung Hamburger Juden nach und in Lettland 39 Tage Curiohaus Der Prozess der britischen Militärregierung gegen die ehemalige Lagerleitung des KZ Neuengam- me 18. März bis 3. Mai 1946 im Curiohaus Hamburg Sonderbehand- lung nach Abschluss der Akte Die Unterdrückung sogenannter „Ost“- und „Fremdarbeiter“ durch die Hamburger Gestapo Plötzlicher Herztod durch Erschießen NS-Wehrmachtjustiz und Hinrichtungen -

Framing Through Names and Titles in German

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 4924–4932 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Doctor Who? Framing Through Names and Titles in German Esther van den Berg∗z, Katharina Korfhagey, Josef Ruppenhofer∗z, Michael Wiegand∗ and Katja Markert∗y ∗Leibniz ScienceCampus, Heidelberg/Mannheim, Germany yInstitute of Computational Linguistics, Heidelberg University, Germany zInstitute for German Language, Mannheim, Germany fvdberg|korfhage|[email protected] fruppenhofer|[email protected] Abstract Entity framing is the selection of aspects of an entity to promote a particular viewpoint towards that entity. We investigate entity framing of political figures through the use of names and titles in German online discourse, enhancing current research in entity framing through titling and naming that concentrates on English only. We collect tweets that mention prominent German politicians and annotate them for stance. We find that the formality of naming in these tweets correlates positively with their stance. This confirms sociolinguistic observations that naming and titling can have a status-indicating function and suggests that this function is dominant in German tweets mentioning political figures. We also find that this status-indicating function is much weaker in tweets from users that are politically left-leaning than in tweets by right-leaning users. This is in line with observations from moral psychology that left-leaning and right-leaning users assign different importance to maintaining social hierarchies. Keywords: framing, naming, Twitter, German, stance, sentiment, social media 1. Introduction An interesting language to contrast with English in terms of naming and titling is German. -

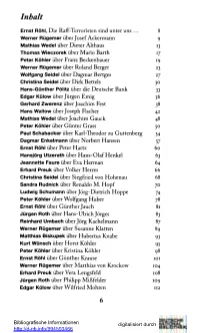

Inhalt Ernst Röhl, Die Raff-Terroristen Sind Unter Uns

Inhalt Ernst Röhl, Die Raff-Terroristen sind unter uns ... 8 Werner Rügemer über Josef Ackermann 9 Mathias Wedel über Dieter Althaus 13 Thomas Wieczorek über Mario Barth 17 Peter Köhler über Franz Beckenbauer 19 Werner Rügemer über Roland Berger 23 Wolfgang Seidel über Dagmar Bertges 27 Christina Seidel über Dirk Bettels 30 Hans-Günther Pölitz über die Deutsche Bank 33 Edgar Külow über Jürgen Emig 36 Gerhard Zwerenz über Joachim Fest 38 Hans Wallow über Joseph Fischer 42 Mathias Wedel über Joachim Gauck 48 Peter Köhler über Günter Grass 50 Paul Schabacker über Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg 54 Dagmar Enkelmann über Norbert Hansen 57 Ernst Röhl über Peter Hartz 60 Hansjörg Utzerath über Hans-Olaf Henkel 63 Jeannette Faure über Eva Herman 64 Erhard Preuk über Volker Herres 66 Christina Seidel über Siegfried von Hohenau 68 Sandra Rudnick über Renaldo M. Hopf 70 Ludwig Schumann über Jörg-Dietrich Hoppe 74 Peter Köhler über Wolfgang Huber 78 Ernst Röhl über Günther Jauch 81 Jürgen Roth über Hans-Ulrich Jorges 83 Reinhard Limbach über Jörg Kachelmann 87 Werner Rügemer über Susanne Klatten 89 Matthias Biskupek über Hubertus Knabe 93 Kurt Wünsch über Horst Köhler 95 Peter Köhler über Kristina Köhler 98 Ernst Röhl über Günther Krause 101 Werner Rügemer über Matthias von Krockow 104 Erhard Preuk über Vera Lengsfeld 108 Jürgen Roth über Philipp Mißfelder 109 Edgar Külow über Wilfried Mohren 112 Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch http://d-nb.info/994503466 Paul Schabacker über Franz Müntefering 115 Christoph Hofrichter über Günther Oettinger 120 Reinhard Limbach über Hubertus Pellengahr 122 Stephan Krull über Ferdinand Piëch 123 Ernst Röhl über Heinrich von Pierer 127 Paul Schabacker über Papst Benedikt XVI. -

![Detering | Was Heißt Hier »Wir«? [Was Bedeutet Das Alles?] Heinrich Detering Was Heißt Hier »Wir«? Zur Rhetorik Der Parlamentarischen Rechten](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3046/detering-was-hei%C3%9Ft-hier-%C2%BBwir%C2%AB-was-bedeutet-das-alles-heinrich-detering-was-hei%C3%9Ft-hier-%C2%BBwir%C2%AB-zur-rhetorik-der-parlamentarischen-rechten-173046.webp)

Detering | Was Heißt Hier »Wir«? [Was Bedeutet Das Alles?] Heinrich Detering Was Heißt Hier »Wir«? Zur Rhetorik Der Parlamentarischen Rechten

Detering | Was heißt hier »wir«? [Was bedeutet das alles?] Heinrich Detering Was heißt hier »wir«? Zur Rhetorik der parlamentarischen Rechten Reclam Reclams UniveRsal-BiBliothek Nr. 19619 2019 Philipp Reclam jun. Verlag GmbH, Siemensstraße 32, 71254 Ditzingen Gestaltung: Cornelia Feyll, Friedrich Forssman Druck und Bindung: Kösel GmbH & Co. KG, Am Buchweg 1, 87452 Altusried-Krugzell Printed in Germany 2019 Reclam, UniveRsal-BiBliothek und Reclams UniveRsal-BiBliothek sind eingetragene Marken der Philipp Reclam jun. GmbH & Co. KG, Stuttgart ISBn 978-3-15-019619-9 Auch als E-Book erhältlich www.reclam.de Inhalt Reizwörter und Leseweisen 7 Wir oder die Barbarei 10 Das System der Zweideutigkeit 15 Unser Deutschland, unsere Vernichtung, unsere Rache 21 Ich und meine Gemeinschaft 30 Tausend Jahre, zwölf Jahre 34 Unsere Sprache, unsere Kultur 40 Anmerkungen 50 Nachbemerkung 53 Leseempfehlungen 58 Über den Autor 60 »Sie haben die unglaubwürdige Kühnheit, sich mit Deutschland zu verwechseln! Wo doch vielleicht der Augenblick nicht fern ist, da dem deutschen Volke das Letzte daran gelegen sein wird, nicht mit ihnen verwechselt zu werden.« Thomas Mann, Ein Briefwechsel (1936) Reizwörter und Leseweisen Die Hitlerzeit – ein »Vogelschiss«; die in Hamburg gebo- rene SPD-Politikerin Aydan Özoğuz – ein Fall, der »in Ana- tolien entsorgt« werden sollte; muslimische Flüchtlinge – »Kopftuchmädchen und Messermänner«: Formulierungen wie diese haben in den letzten Jahren und Monaten im- mer von neuem für öffentliche Empörung, für Gegenreden und Richtigstellungen -

Politische Jugendstudie Von BRAVO Und Yougov

Politische Jugendstudie von BRAVO und YouGov © 2017 YouGov Deutschland GmbH Veröffentlichungen - auch auszugsweise - bedürfen der schriftlichen Zustimmung durch die Bauer Media Group und die YouGov Deutschland GmbH. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Zusammenfassung 2. Ergebnisse 3. Untersuchungsdesign 4. Über YouGov und Bauer Media Group © YouGov 2017 – Politische Jugendstudie von Bravo und YouGov 2 Zusammenfassung 3 Zusammenfassung I Politisches Interesse § Das politische Interesse bei den jugendlichen Deutschen zwischen 14 und 17 Jahren fällt sehr gemischt aus (ca. 1/3 stark interessiert, 1/3 mittelmäßig und 1/3 kaum interessiert). Das Vorurteil über eine politisch desinteressierte Jugend lässt sich nicht bestätigen. § Kontaktpunkte zu politischen Themen haben die Jugendlichen vor allem in der Schule (75 Prozent). An zweiter Stelle steht die Familie (57 Prozent), gefolgt von den Freunden (47 Prozent). Vor allem die politisch stark Interessierten diskutieren politische Themen auch im Internet (17 Prozent Gesamt). § Nur ein gutes Drittel beschäftigt sich intensiv und regelmäßig mit politischen Themen . Bei ähnlich vielen spielt Politik im eigenem Umfeld keine große Rolle. Dennoch erkennt der Großteil der Jugendlichen (80 Prozent) die Bedeutung von Wahlen, um die eigenen Interessen vertreten zu lassen. Eine Mehrheit (65 Prozent) wünscht sich ebenfalls mehr politisches Engagement der Menschen. Bei Jungen zeigt sich dabei eine stärkere Beschäftigung mit dem Thema Politik als bei Mädchen. Informationsverhalten § Ihrem Alter entsprechend informieren sich die Jugendlichen am häufigsten im Schulunterricht über politische Themen (51 Prozent „sehr häufig“ oder „häufig“) . An zweiter Stelle steht das Fernsehen (48 Prozent), gefolgt von Gesprächen mit Familie, Bekannten oder Freunden (43 Prozent). Mit News-Apps und sozialen Netzwerken folgen danach digitale Kanäle. Print-Ausgaben von Zeitungen und Zeitschriften spielen dagegen nur eine kleinere Rolle. -

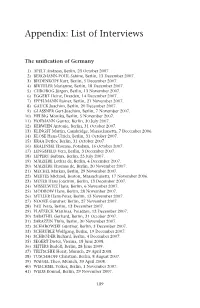

Appendix: List of Interviews

Appendix: List of Interviews The unification of Germany 1) APELT Andreas, Berlin, 23 October 2007. 2) BERGMANN-POHL Sabine, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 3) BIEDENKOPF Kurt, Berlin, 5 December 2007. 4) BIRTHLER Marianne, Berlin, 18 December 2007. 5) CHROBOG Jürgen, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 6) EGGERT Heinz, Dresden, 14 December 2007. 7) EPPELMANN Rainer, Berlin, 21 November 2007. 8) GAUCK Joachim, Berlin, 20 December 2007. 9) GLÄSSNER Gert-Joachim, Berlin, 7 November 2007. 10) HELBIG Monika, Berlin, 5 November 2007. 11) HOFMANN Gunter, Berlin, 30 July 2007. 12) KERWIEN Antonie, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 13) KLINGST Martin, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 7 December 2006. 14) KLOSE Hans-Ulrich, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 15) KRAA Detlev, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 16) KRALINSKI Thomas, Potsdam, 16 October 2007. 17) LENGSFELD Vera, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 18) LIPPERT Barbara, Berlin, 25 July 2007. 19) MAIZIÈRE Lothar de, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 20) MAIZIÈRE Thomas de, Berlin, 20 November 2007. 21) MECKEL Markus, Berlin, 29 November 2007. 22) MERTES Michael, Boston, Massachusetts, 17 November 2006. 23) MEYER Hans Joachim, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 24) MISSELWITZ Hans, Berlin, 6 November 2007. 25) MODROW Hans, Berlin, 28 November 2007. 26) MÜLLER Hans-Peter, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 27) NOOKE Günther, Berlin, 27 November 2007. 28) PAU Petra, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 29) PLATZECK Matthias, Potsdam, 12 December 2007. 30) SABATHIL Gerhard, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 31) SARAZZIN Thilo, Berlin, 30 November 2007. 32) SCHABOWSKI Günther, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 33) SCHÄUBLE Wolfgang, Berlin, 19 December 2007. 34) SCHRÖDER Richard, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 35) SEGERT Dieter, Vienna, 18 June 2008. -

Plenarprotokoll 15/56

Plenarprotokoll 15/56 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 56. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 3. Juli 2003 Inhalt: Begrüßung des Marschall des Sejm der Repu- rung als Brücke in die Steuerehr- blik Polen, Herrn Marek Borowski . 4621 C lichkeit (Drucksache 15/470) . 4583 A Begrüßung des Mitgliedes der Europäischen Kommission, Herrn Günter Verheugen . 4621 D in Verbindung mit Begrüßung des neuen Abgeordneten Michael Kauch . 4581 A Benennung des Abgeordneten Rainder Tagesordnungspunkt 19: Steenblock als stellvertretendes Mitglied im a) Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Michael Programmbeirat für die Sonderpostwert- Meister, Friedrich Merz, weiterer Ab- zeichen . 4581 B geordneter und der Fraktion der CDU/ Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisung . 4582 D CSU: Steuern: Niedriger – Einfa- cher – Gerechter Erweiterung der Tagesordnung . 4581 B (Drucksache 15/1231) . 4583 A b) Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Hermann Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 1: Otto Solms, Dr. Andreas Pinkwart, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion Abgabe einer Erklärung durch den Bun- der FDP: Steuersenkung vorziehen deskanzler: Deutschland bewegt sich – (Drucksache 15/1221) . 4583 B mehr Dynamik für Wachstum und Be- schäftigung 4583 A Gerhard Schröder, Bundeskanzler . 4583 C Dr. Angela Merkel CDU/CSU . 4587 D in Verbindung mit Franz Müntefering SPD . 4592 D Dr. Guido Westerwelle FDP . 4596 D Tagesordnungspunkt 7: Krista Sager BÜNDNIS 90/ a) Erste Beratung des von den Fraktionen DIE GRÜNEN . 4600 A der SPD und des BÜNDNISSES 90/ DIE GRÜNEN eingebrachten Ent- Dr. Guido Westerwelle FDP . 4603 B wurfs eines Gesetzes zur Förderung Krista Sager BÜNDNIS 90/ der Steuerehrlichkeit DIE GRÜNEN . 4603 C (Drucksache 15/1309) . 4583 A Michael Glos CDU/CSU . 4603 D b) Erste Beratung des von den Abgeord- neten Dr. Hermann Otto Solms, Hubertus Heil SPD . -

Mitteilung Tagesordnung

19. Wahlperiode Ausschuss für Inneres und Heimat Mitteilung Berlin, den 4. Februar 2021 Die 119. Sitzung des Ausschusses für Inneres und Sekretariat Heimat Telefon: +49 30 227-32858 Fax: +49 30 227-36994 findet statt am Mittwoch, dem 10. Februar 2021, 10:00 Uhr Sitzungssaal im Reichstagsgebäude, Raum 3 N 001 Telefon: 030/227-33246 (Fraktionssitzungssaal der CDU/CSU) Fax: 030/227-56084 11011 Berlin, Platz der Republik 1 Achtung! Abweichender Sitzungsort! Tagesordnung Tagesordnungspunkt 1 Bericht des Bundesministeriums des Innern, für Bau und Heimat über die aktuellen innenpoliti- schen Maßnahmen angesichts der COVID-19-Pandemie Tagesordnungspunkt 2 a) Gesetzentwurf der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und Federführend: SPD Ausschuss für Inneres und Heimat Mitberatend: Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Erprobung weiterer Ausschuss für Recht und Verbraucherschutz elektronischer Verfahren zur Erfüllung der beson- Ausschuss für Wirtschaft und Energie deren Meldepflicht in Beherbergungsstätten Ausschuss für Tourismus Ausschuss Digitale Agenda BT-Drucksache 19/26176 Berichterstatter/in: Abg. Marc Henrichmann [CDU/CSU] Abg. Helge Lindh [SPD] Abg. Dr. Christian Wirth [AfD] Abg. Manuel Höferlin [FDP] Abg. Ulla Jelpke [DIE LINKE.] Abg. Dr. Konstantin von Notz [BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN] Voten angefordert für den: 10.02.2021 19. Wahlperiode Seite 1 von 13 Ausschuss für Inneres und Heimat b) Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Marcel Klinge, Federführend: Manuel Höferlin, Michael Theurer, weiterer Abge- Ausschuss für Inneres und Heimat ordneter und der Fraktion der FDP Mitberatend: Ausschuss für Wirtschaft und Energie Digitale Signatur von Meldescheinen in Beherber- Ausschuss für Tourismus gungsstätten – Bürokratie abbauen Berichterstatter/in: BT-Drucksache 19/9223 Abg. Marc Henrichmann [CDU/CSU] Abg. Helge Lindh [SPD] Abg. -

Britta Haßelmann (BÜNDNIS 90/ Dr

Plenarprotokoll 19/103 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 103. Sitzung Berlin, Mittwoch, den 5. Juni 2019 Inhalt: Ausschussüberweisungen 12527 A Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12531 B Alexander Graf Lambsdorff (FDP) 12531 D Tagesordnungspunkt 1: Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12532 A Befragung der Bundesregierung Alexander Graf Lambsdorff (FDP) 12532 A Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12527 C Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12532 B Markus Frohnmaier (AfD) 12528 C Matern von Marschall (CDU/CSU) 12532 D Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12528 D Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12533 A Markus Frohnmaier (AfD) 12529 A Eva-Maria Schreiber (DIE LINKE) 12533 B Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12529 A Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12533 B Dr Christoph Hoffmann (FDP) 12529 B Eva-Maria Schreiber (DIE LINKE) 12533 C Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12529 C Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12533 D Dr Christoph Hoffmann (FDP) 12529 C Ottmar von Holtz (BÜNDNIS 90/ Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12529 C DIE GRÜNEN) 12533 D Volker Kauder (CDU/CSU) 12529 D Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12534 A Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12529 D Ottmar von Holtz (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) 12534 B Helin Evrim Sommer (DIE LINKE) 12530 A Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12534 B Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12530 B Dietmar Friedhoff (AfD) 12534 C Helin Evrim Sommer (DIE LINKE) 12530 B Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12534 C Dr Gerd Müller, Bundesminister BMZ 12530 C Dietmar Friedhoff (AfD) 12534 D Agnieszka Brugger -

The Bells in Their Silence: Travels Through Germany'

H-German Buse on Gorra, 'The Bells in their Silence: Travels Through Germany' Review published on Sunday, January 1, 2006 Michael Gorra. The Bells in their Silence: Travels Through Germany. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004. xvii + 211 pp. $26.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-691-11765-2. Reviewed by Dieter K. Buse (Department of History, Laurentian University)Published on H- German (January, 2006) Travel Writing on Postwar Germany Ulrich Giersch's book, Walking Through Time in Weimar: A Criss-Cross Guide to Cultural History, Weaving Between Goethe's Home and Buchenwald (1999) set Goethe's idyllic house, garden, and literary works against the horrors of the nearby Buchenwald concentration camp. Ralph Giordano, the moralist and philosopher who had previously taken Germans to task for not addressing their past, authored Deutschlandreise: Aufzeichnung aus einer schwierigen Heimat (1998). He too noted the Weimar and Buchenwald contrast as he wandered throughout his country revealing warts and novelties. He acknowledged the difficulties of selection as he criss-crossed the past and the present of his homeland trying to find out what Germans thought. Interwoven with his findings were allusions to earlier literary works, including other travel accounts. He concluded that in 1996 his country was a very different place than during the first half of the twentieth century. Gone were the militarists, the loud antisemites, the horrid jurists, the révanchists, and the profiteers from Rhine and Ruhr whom Kurt Tucholsky satirized so well. Giordano closed by citing Tucholsky on the necessity for "the quiet love of our Heimat" adding a definitive "Ja!" The French travel writer Patrick Démerin in Voyage en Allemagne (1988) wrote just before the Berlin Wall opened. -

German Post-Socialist Memory Culture

8 HERITAGE AND MEMORY STUDIES Bouma German Post-Socialist MemoryGerman Culture Post-Socialist Amieke Bouma German Post-Socialist Memory Culture Epistemic Nostalgia FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS German Post-Socialist Memory Culture FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Heritage and Memory Studies This ground-breaking series examines the dynamics of heritage and memory from a transnational, interdisciplinary and integrated approaches. Monographs or edited volumes critically interrogate the politics of heritage and dynamics of memory, as well as the theoretical implications of landscapes and mass violence, nationalism and ethnicity, heritage preservation and conservation, archaeology and (dark) tourism, diaspora and postcolonial memory, the power of aesthetics and the art of absence and forgetting, mourning and performative re-enactments in the present. Series Editors Ihab Saloul and Rob van der Laarse, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands Editorial Board Patrizia Violi, University of Bologna, Italy Britt Baillie, Cambridge University, UK Michael Rothberg, University of Illinois, USA Marianne Hirsch, Columbia University, USA Frank van Vree, NIOD and University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS German Post-Socialist Memory Culture Epistemic Nostalgia Amieke Bouma Amsterdam University Press FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Cover illustration: Kalter Abbruch Source: Bernd Kröger, Adobe Stock Cover -

Afd) a New Actor in the German Party System

INTERNATIONAL POLICY ANALYSIS Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) A New Actor in the German Party System MARCEL LEWANDOWSKY March 2014 The Alternative für Deutschland (AfD – Alternative for Germany) is a new party in the conservative/economic liberal spectrum of the German party system. At present it is a broad church encompassing various political currents, including classic ordo-liberals, as well as euro-sceptics, conservatives and right-wingers of different stripes. The AfD has not yet defined its political platform, which is still shaped by periodic flare-ups of different groups positioning themselves within the party or by individual members. The AfD’s positions are mainly critical of Europe and the European Union. It advo- cates winding up the euro area, restoration of national currencies or small currency unions and renationalisation of decision-making processes in the EU. When it comes to values it represents conservative positions. As things stand at the moment, given its rudimentary political programme, the AfD is not a straightforward right-wing populist party in the traditional sense. The populist tag stems largely from the party’s campaigning, in which it poses as the mouthpiece of »the people« and of the »silent majority«. With regard to its main topics, the AfD functions as a centre-right protest party. At the last Bundestag election in 2013 it won voters from various political camps. First studies show that although its sympathisers regard themselves as occupying the political centre, they represent very conservative positions on social and integra- tion-policy issues. Marcel Lewandowsky | ALternativE füR DEutschland (AfD) Content 1. Origins and Development.