Troy Last War of the Heroic Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odyssey Glossary of Names

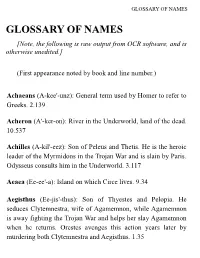

GLOSSARY OF NAMES GLOSSARY OF NAMES [Note, the following is raw output from OCR software, and is otherwise unedited.] (First appearance noted by book and line number.) Achaeans (A-kee'-unz): General term used by Homer to reFer to Greeks. 2.139 Acheron (A'-ker-on): River in the Underworld, land of the dead. 10.537 Achilles (A-kil'-eez): Son of Peleus and Thetis. He is the heroic leader of the Myrmidons in the Trojan War and is slain by Paris. Odysseus consults him in the Underworld. 3.117 Aeaea (Ee-ee'-a): Island on which Circe lives. 9.34 Aegisthus (Ee-jis'-thus): Son of Thyestes and Pelopia. He seduces Clytemnestra, wife of Agamemnon, while Agamemnon is away fighting the Trojan War and helps her slay Agamemnon when he returns. Orestes avenges this action years later by murdering both Clytemnestra and Aegisthus. 1.35 GLOSSARY OF NAMES Aegyptus (Ee-jip'-tus): The Nile River. 4.511 Aeolus (Ee'-oh-lus): King of the island Aeolia and keeper of the winds. 10.2 Aeson (Ee'-son): Son oF Cretheus and Tyro; father of Jason, leader oF the Argonauts. 11.262 Aethon (Ee'-thon): One oF Odysseus' aliases used in his conversation with Penelope. 19.199 Agamemnon (A-ga-mem'-non): Son oF Atreus and Aerope; brother of Menelaus; husband oF Clytemnestra. He commands the Greek Forces in the Trojan War. He is killed by his wiFe and her lover when he returns home; his son, Orestes, avenges this murder. 1.36 Agelaus (A-je-lay'-us): One oF Penelope's suitors; son oF Damastor; killed by Odysseus. -

JONATHAN FENNO Curriculum Vitae

JONATHAN FENNO Curriculum Vitae SPECIAL INTERESTS Greek and Latin Poetry, Greek Religion, Ancient Athletics, Romans in Cinema DISSERTATION Poet, Athletes, and Heroes: Theban and Aeginetan Identity in Pindar's Aeginetan Odes DEGREES IN CLASSICS 6/1995 Ph.D., UCLA 6/1989 M.A., UCLA 5/1986 B.A. Summa cum Laude, Concordia College, Moorhead, Minnesota ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2009– Associate Professor, University of Mississippi 2002–09 Assistant Professor, University of Mississippi 2002 Adjunct Assistant Professor, Gettysburg College 1999–2001 Assistant Professor, College of Charleston 1996–99 Visiting Assistant Professor, College of Charleston 1995–96 Lecturer, UCLA 1988–95 Teaching Assistant, UCLA ARTICLES PUBLISHED “The Wrath and Vengeance of Swift-Footed Aeneas in Iliad XIII” Phoenix 62 (2008) 145–61 “The Mist Shed by Zeus in Iliad XVII” The Classical Journal 104.1 (2008) 1–9 “‘A Great Wave against the Stream’: Water Imagery in Iliadic Battle Scenes” American Journal of Philology 126.4 (2005) 475–504 “Semonides 7.43: A Hard/Stubborn Ass” Mnemosyne 58.3 (2005) 408–11 “Setting Aright the House of Themistius in Pindar’s Nemean 5 and Isthmian 6” Hermes 133.3 (2005) 294–311 “Praxidamas' Crown and the Omission at Pindar Nemean 6.18” Classical Quarterly 53.2 (2003) 338–46 PAPERS PRESENTED “Typical Heroic Careers and Large-Scale Design in the Iliad” CAMWS 2015 “Odysseus and Hector in the Iliad” CAMWS 2014 “The Schedius Sequence and the Alternating Rhythm of the Iliadic Battle Narrative” CAMWS 2013 “Stretching out the Battle in Equal Portions: An Iliadic -

Dares Phrygius' De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological Commentary and Translation

Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Dares Phrygius' De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological Commentary and Translation Jonathan Cornil Scriptie voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van Master in de Taal- en letterkunde (Latijn – Engels) 2011-2012 Promotor: Prof. Dr. W. Verbaal ii Table of Contents Table of Contents iii Foreword v Introduction vii Chapter I. De Excidio Trojae Historia: Philological and Historical Comments 1 A. Dares and His Historia: Shrouded in Mystery 2 1. Who Was ‘Dares the Phrygian’? 2 2. The Role of Cornelius Nepos 6 3. Time of Origin and Literary Environment 9 4. Analysing the Formal Characteristics 11 B. Dares as an Example of ‘Rewriting’ 15 1. Homeric Criticism and the Trojan Legacy in the Middle Ages 15 2. Dares’ Problematic Connection with Dictys Cretensis 20 3. Comments on the ‘Lost Greek Original’ 27 4. Conclusion 31 Chapter II. Translations 33 A. Translating Dares: Frustra Laborat, Qui Omnibus Placere Studet 34 1. Investigating DETH’s Style 34 2. My Own Translations: a Brief Comparison 39 3. A Concise Analysis of R.M. Frazer’s Translation 42 B. Translation I 50 C. Translation II 73 D. Notes 94 Bibliography 95 Appendix: the Latin DETH 99 iii iv Foreword About two years ago, I happened to be researching Cornelius Nepos’ biography of Miltiades as part of an assignment for a class devoted to the study of translating Greek and Latin texts. After heaping together everything I could find about him in the library, I came to the conclusion that I still needed more information. So I decided to embrace my identity as a loyal member of the ‘Internet generation’ and began my virtual journey through the World Wide Web in search of articles on Nepos. -

'The Judgement of Paris' from Robert Graves

Extract, regarding ‘The Judgement of Paris’, from Robert Graves, The Greek Myths: Volume Two. h. Paris's noble birth was soon disclosed by his outstanding beauty, intelligence, and strength: when little more than a child, he routed a band of cattle-thieves and recovered the cows they had stolen, thus winning the surname Alexander.1 Though ranking no higher than a slave at this time, Paris became the chosen lover of Genone, daughter of the river Oeneus, a fountain-nymph. She had been taught the art of prophecy by Rhea, and that of medicine by Apollo while he was acting as Laomedon's herdsman. Paris and Oenone used to herd their flocks and hunt together; he carved her name in the bark of beech-trees and poplars.2 His chief amusement was setting Agelaus's bulls to fight one another; he would crown the victor with flowers, and the loser with straw. When one bull began to win consistently, Paris pitted it against the champions of his neighbours' herds, all of which were defeated. At last he offered to set a golden crown upon the horns of any bull that could overcome his own; so, for a jest, Ares turned himself into a bull, and won the prize. Paris's unhesitating award of this crown to Ares surprised and pleased the gods as they watched from Olympus; which is why Zeus chose him to arbitrate between the three goddesses.3 i. He was herding his cattle on Mount Gargarus, the highest peak of Ida, when Hermes, accompanied by Hera, Athene, and Aphrodite, delivered the golden apple and Zeus's message: 'Paris, since you are as handsome as you are wise in affairs of the heart, Zeus commands you to judge which of these goddesses is the fairest.' Paris accepted the apple doubtfully. -

1 Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer's Iliad Senior Thesis

Divine Intervention and Disguise in Homer’s Iliad Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Undergraduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Classical Studies Professor Joel Christensen, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Joana Jankulla May 2018 Copyright by Joana Jankulla 1 Copyright by Joana Jankulla © 2018 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Joel Christensen. Thank you, Professor Christensen for guiding me through this process, expressing confidence in me, and being available whenever I had any questions or concerns. I would not have been able to complete this work without you. Secondly, I would like to thank Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Professor Cheryl Walker for reading my thesis and providing me with feedback. The Classics Department at Brandeis University has been an instrumental part of my growth in my four years as an undergraduate, and I am eternally thankful to all the professors and staff members in the department. Thank you to my friends, specifically Erica Theroux, Sarah Jousset, Anna Craven, Rachel Goldstein, Taylor McKinnon and Georgie Contreras for providing me with a lot of emotional support this year. I hope you all know how grateful I am for you as friends and how much I have appreciated your love this year. Thank you to my mom for FaceTiming me every time I was stressed about completing my thesis and encouraging me every step of the way. Finally, thank you to Ian Leeds for dropping everything and coming to me each time I needed it. -

Astrocladistics of the Jovian Trojan Swarms

MNRAS 000,1–26 (2020) Preprint 23 March 2021 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 Astrocladistics of the Jovian Trojan Swarms Timothy R. Holt,1,2¢ Jonathan Horner,1 David Nesvorný,2 Rachel King,1 Marcel Popescu,3 Brad D. Carter,1 and Christopher C. E. Tylor,1 1Centre for Astrophysics, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, QLD, Australia 2Department of Space Studies, Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO. USA. 3Astronomical Institute of the Romanian Academy, Bucharest, Romania. Accepted XXX. Received YYY; in original form ZZZ ABSTRACT The Jovian Trojans are two swarms of small objects that share Jupiter’s orbit, clustered around the leading and trailing Lagrange points, L4 and L5. In this work, we investigate the Jovian Trojan population using the technique of astrocladistics, an adaptation of the ‘tree of life’ approach used in biology. We combine colour data from WISE, SDSS, Gaia DR2 and MOVIS surveys with knowledge of the physical and orbital characteristics of the Trojans, to generate a classification tree composed of clans with distinctive characteristics. We identify 48 clans, indicating groups of objects that possibly share a common origin. Amongst these are several that contain members of the known collisional families, though our work identifies subtleties in that classification that bear future investigation. Our clans are often broken into subclans, and most can be grouped into 10 superclans, reflecting the hierarchical nature of the population. Outcomes from this project include the identification of several high priority objects for additional observations and as well as providing context for the objects to be visited by the forthcoming Lucy mission. -

Helen of Troy

T H E P O E T I C A L WO R K S A N D R E W L A N G I V OL . V TH E P O E T I CAL Wo rm s * W L A 3 ! d i b N E ted y M rs. L A G I N F 0UR VOLUM ES . VOL V . I With Port r ai n m (J r ee o L o g a l s n 63 L . P a te rn oste r R ow n E C . 39 , Lo don , . 4, N ew Y o rk Tor n to , o Bo m ba Ca c u t ta a nd M a a s y , l , d r $3“ k; on( 9 e! TH E PO ET I C AL WO R K S dited N G E by M r s . LA I N F OUR V OLUM ES V O L . I V 8 Ll O 3 \V ith P or tr a i ’ a tc rn ost r R w do n e o Lo n E C . , , . N ew Y r k T r n t o , o o o B m ba C a c u a a n d M a a s o y , l t t , d r fi %L eff M a d e i n! G r ea t TA BLE OF CON TE N TS V OLUM E I V XV H EL EN OF TR OY D edic a t io n : To a ll Old F ri e nd s The Com i ng ofP a ris Th e S p e ll ofAp h rodite Th e F light ofH e l e n Th e D e a th ofCo ry t h u s Th e \V a r Th e S a c k o fT ro T h e R u n o fH n y . -

Nick Susa Epic Mythomemology – the Iliad Book 1: Achilles Was Fighting

Nick Susa Epic Mythomemology – The Iliad Book 1: Achilles was fighting alongside Agamemnon, the King of Argos, during the Trojan war. After winning a battle each was given a war prize, a woman. Achilles was given Briseis, and Agamemnon was given Chryseis. However, the father of Chryseis, Chryses, who was also a priest of Apollo, wasn’t ready to part with his daughter and came with a ransom for his daughter for King Agamemnon. Agamemnon refused the ransom in favor of keeping Chryseis and threatened the priest. Horrified and upset the priest (Chryses) calls upon Apollo and asks him to put a plague upon the Achaean armies, one of which Agamemnon leads. For nine days the armies were struck with a plague, on the tenth Achilles called a meeting to find the reason for the plague. Calchas, a prophet and follower of Apollo, being protected by Achilles, explains that Agamemnon refusing the ransom was the reason for the plague and he must return the girl and make a sacrifice of one hundred cows to Apollo in order to end the plague. Agamemnon decides to appease Apollo, but only if he can take away Achilles war prize, Briseis. Achilles doesn’t believe that Agamemnon should gain Briseis, so the two begin to argue. Achilles decides that he and his men shall not fight in the war because of Agamemnon’s actions. After Agamemnon takes Briseis away, Achilles cries and prays to his mother, Thetis, asking her to have Zeus grant the Achaean armies many loses. Zeus was not around to be asked though, but after twelve days, he returns and promises to Thetis that he will grant the Trojans many victories and the Achaeans many losses. -

WRATH of ACHILLES: the MYTHS of the TROJAN WAR “The Feast of Peleus”

SING, GODDESS OF THE WRATH OF ACHILLES: THE MYTHS OF THE TROJAN WAR “The Feast Of Peleus” E. Burne-Jones (1872-81) Eris The Greek Goddess of Chaos Paris and the nymph Oinone happy on Mt. Ida Peter Paul Rubens, “Judgment Of Paris” Salvador Dali, “The Judgment of Paris” (1960-64) “Paris and Helen,” Jacques-Louis David (1788) “The Abduction of Helen” From an illuminated edition of Ovid’s Metamorphosis (late 15th c.) OATH OF TYNDAREUS When Helen reached marriageable age, the greatest kings and warriors from all Greece sought to win her hand. They brought magnificent gifts to her mortal father Tyndareus. The suitors included Ajax, Peleus, Diomedes, Patroclus and Odysseus. In return for Tyndareus’ niece Penelope in marriage, Odysseus drew up an oath to be taken by all the suitors. They would swear to accept the choice of Tyndareus. If any man ever took Helen by force, they would fight to regain her for her lawful husband. Tyndareus selected Menelaus, king of Sparta, who had brought the most valuable gifts. “Odysseus’ Induction,” Heywood Hardy (1874) “Thetis Dips Achilles Into The River Syx” Antoine Borel (18th c.) Achilles taught to play the lyre by Chiron Jan de Bray, “The Discovery of Achilles Among the Daughters of Lycomedes” [1664] Aulis today Achilles wounds Telephus in Mysia Iphigenia, Achilles, Clytemnestra and Agamemnon at Aulis “Sacrifice of Iphigenia at Aulis,” A wall painting from the House of the Tragic Poet at Pompeii 63-70 CE Peter Pietersz Lastman, “Orestes and Pylades Disputing the Altar” (1614) Philoctetes with Heracles’ bow on Lemnos Protesilaus steps ashore at Troy Patroclus separates Briseis from Achilles Briseis and Agamemnon Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, “Jupiter and Thetis” (1811) Paris and Menelaus in single combat Aeneas and Aphrodite were both wounded by Diomedes “Achilles Receives Agamemnon’s Messengers,” Jacques-Louis David (1801) “Helen on the Walls of Troy,” -Gustave Moreau, c. -

(2018). Gazing at Helen with Stesichorus. in A. Kampakoglou, & A

Finglass, P. J. (2018). Gazing at Helen with Stesichorus. In A. Kampakoglou, & A. Novokhatko (Eds.), Gaze, Vision, and Visuality in Ancient Greek Literature (pp. 140–159). (Trends in Classics Supplements; Vol. 54). Walter de Gruyter GmbH. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110571288-007 Peer reviewed version License (if available): CC BY-NC-ND Link to published version (if available): 10.1515/9783110571288-007 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the accepted author manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via De Gruyter at DOI 10.1515/9783110571288-007. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ GAZING AT HELEN WITH STESICHORUS P. J. Finglass οἳ δ’ ὡς οὖν εἴδονθ’ Ἑλένην ἐπὶ πύργον ἰοῦσαν, 155 ἦκα πρὸς ἀλλήλους ἔπεα πτερόεντ’ ἀγόρευον· οὐ νέμεσις Τρῶας καὶ ἐϋκνήμιδας Ἀχαιοὺς τοιῆιδ’ ἀμφὶ γυναικὶ πολὺν χρόνον ἄλγεα πάσχειν· αἰνῶς ἀθανάτηισι θεῆις εἰς ὦπα ἔοικεν· ἀλλὰ καὶ ὧς τοίη περ ἐοῦσ’ ἐν νηυσὶ νεέσθω, 160 μηδ’ ἡμῖν τεκέεσσί τ’ ὀπίσσω πῆμα λίποιτο. Hom. Il. 3.154-60 When they saw Helen on her way to the tower, they began to speak winged words quietly to each other. ‘It is no cause for anger that the Trojans and well-greaved Achaeans should long suffer pains on behalf of such a woman. -

Trojan War - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Trojan War from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia for the 1997 Film, See Trojan War (Film)

5/14/2014 Trojan War - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Trojan War From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For the 1997 film, see Trojan War (film). In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen Trojan War from her husband Menelaus king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and has been narrated through many works of Greek literature, most notably through Homer's Iliad. The Iliad relates a part of the last year of the siege of Troy; its sequel, the Odyssey describes Odysseus's journey home. Other parts of the war are described in a cycle of epic poems, which have survived through fragments. Episodes from the war provided material for Greek tragedy and other works of Greek literature, and for Roman poets including Virgil and Ovid. The war originated from a quarrel between the goddesses Athena, Hera, and Aphrodite, after Eris, the goddess of strife and discord, gave them a golden apple, sometimes known as the Apple of Discord, marked "for the fairest". Zeus sent the goddesses to Paris, who judged that Aphrodite, as the "fairest", should receive the apple. In exchange, Aphrodite made Helen, the most beautiful Achilles tending the wounded Patroclus of all women and wife of Menelaus, fall in love with Paris, who (Attic red-figure kylix, c. 500 BC) took her to Troy. Agamemnon, king of Mycenae and the brother of Helen's husband Menelaus, led an expedition of Achaean The war troops to Troy and besieged the city for ten years because of Paris' Setting: Troy (modern Hisarlik, Turkey) insult. -

Pausanias' Description of Greece

BONN'S CLASSICAL LIBRARY. PAUSANIAS' DESCRIPTION OF GREECE. PAUSANIAS' TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH \VITTI NOTES AXD IXDEX BY ARTHUR RICHARD SHILLETO, M.A., Soiiii'tinie Scholar of Trinity L'olltge, Cambridge. VOLUME IT. " ni <le Fnusnnias cst un homme (jui ne mnnquo ni de bon sens inoins a st-s tlioux." hnniie t'oi. inais i}iii rn>it ou au voudrait croire ( 'HAMTAiiNT. : ftEOROE BELL AND SONS. YOUK STIIKKT. COVKNT (iAKDKX. 188t). CHISWICK PRESS \ C. WHITTINGHAM AND CO., TOOKS COURT, CHANCEKV LANE. fA LC >. iV \Q V.2- CONTEXTS. PAGE Book VII. ACHAIA 1 VIII. ARCADIA .61 IX. BtEOTIA 151 -'19 X. PHOCIS . ERRATA. " " " Volume I. Page 8, line 37, for Atte read Attes." As vii. 17. 2<i. (Catullus' Aft is.) ' " Page 150, line '22, for Auxesias" read Anxesia." A.-> ii. 32. " " Page 165, lines 12, 17, 24, for Philhammon read " Philanimon.'' " " '' Page 191, line 4, for Tamagra read Tanagra." " " Pa ire 215, linu 35, for Ye now enter" read Enter ye now." ' " li I'aijf -J27, line 5, for the Little Iliad read The Little Iliad.'- " " " Page ^S9, line 18, for the Babylonians read Babylon.'' " 7 ' Volume II. Page 61, last line, for earth' read Earth." " Page 1)5, line 9, tor "Can-lira'" read Camirus." ' ; " " v 1'age 1 69, line 1 , for and read for. line 2, for "other kinds of flutes "read "other thites.'' ;< " " Page 201, line 9. for Lacenian read Laeonian." " " " line 10, for Chilon read Cliilo." As iii. 1H. Pago 264, " " ' Page 2G8, Note, for I iad read Iliad." PAUSANIAS. BOOK VII. ACIIAIA.