Tidal Variations in the Sundarbans Estuarine System, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By the Histories of Sea and Fiction in Its Roar: Fathoming the Generic Development of Indian Sea-Fiction in Amitav Ghosh’S Sea of Poppies

ISSN 2249-4529 www.pintersociety.com GENERAL ISSUE VOL: 8, No.: 1, SPRING 2018 UGC APPROVED (Sr. No.41623) BLIND PEER REVIEWED About Us: http://pintersociety.com/about/ Editorial Board: http://pintersociety.com/editorial-board/ Submission Guidelines: http://pintersociety.com/submission-guidelines/ Call for Papers: http://pintersociety.com/call-for-papers/ All Open Access articles published by LLILJ are available online, with free access, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License as listed on http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Individual users are allowed non-commercial re-use, sharing and reproduction of the content in any medium, with proper citation of the original publication in LLILJ. For commercial re-use or republication permission, please contact [email protected] 144 | By the Histories of Sea and Fiction in its Roar: Fathoming the Generic Development of Indian Sea-Fiction in Amitav Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies By the Histories of Sea and Fiction in its Roar: Fathoming the Generic Development of Indian Sea-Fiction in Amitav Ghosh’s Sea of Poppies Smriti Chowdhuri Abstract: Indian literature has betrayed a strange indifference to sea-experience and sea-culture as a subject of literary interest though it cannot overlook the repercussions of sea voyages on Indian social, political and economic conditions specifically after colonization. Consequently, nautical fiction as a category of writing can hardly be traced in the history of Indian literature. Nautical fiction as a substantial body of writing emerged from Anglo-American history of maritime experience. This paper is an attempt to perceive Amitav Ghosh’s novel, Sea of Poppies as an Indian response to the sub-genre. -

As Rich in Beauty As in Historic Sites, North India and Rajasthan Is a Much Visited Region

India P88-135 18/9/06 14:35 Page 92 Rajasthan & The North Introduction As rich in beauty as in historic sites, North India and Rajasthan is a much visited region. Delhi, the entry point for the North can SHOPPING HORSE AND CAMEL SAFARIS take you back with its vibrancy and Specialities include marble inlay work, precious Please contact our reservations team for details. and semi-precious gemstones, embroidered and growth from its Mughal past and British block-printed fabrics, miniature Mughal-style FAIRS & FESTIVALS painting, famous blue pottery, exquisitely carved Get caught up in the excitement of flamboyant rule. The famous Golden Triangle route furniture, costume jewellery, tribal artefacts, and religious festivals celebrated with a special local starts here and takes in Jaipur and then don't forget to get some clothes tailor-made! farvour. onwards to the Taj Mahal at Agra. There’s SHOPPING AREAS Feb - Jaisalmer Desert Festival, Jaisalmer Agra, marble and stoneware inlay work Taj so much to see in the region with Mughal complex, Fatehbad Raod and Sabdar Bazaar. Feb - Taj Mahotsav, Agra influence spreading from Rajasthan in Delhi, Janpath, Lajpat Nagar, Chandini Chowk, Mar - Holi, North India the west to the ornate Hindu temples of Sarojini Nagar and Ajmal Khan Market. Mar - Elephant Festival, Jaipur Khajuraho and Orcha in the east, which Jaipur, Hawa Mahal area, Chowpars for printed Apr - Ganghur Festival, Rajasthan fabrics, Johari Bazaar for jewellery and gems, leads to the holy city of Varanasi where silverware etc. Aug - Sri Krishna Janmasthami, Mathura - Vrindavan pilgrims gather to bathe in the crowded Jodhpur, Sojati Gate and Station area, Tripolia Bazaar, Nai Sarak and Sardar Market. -

WEST BENGAL POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD (Department of Environment, Government of West Bengal)

WEST BENGAL POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD (Department of Environment, Government of West Bengal) Paribesh Bhawan,10A, Block – LA, Sector III, Salt Lake Kolkata – 700 098, Ph.: (033)2335 8212, Fax : (033)2335-8073 Website: www.wbpcb.gov.in Memo No. 2097-5L/WPB/2012/U-00288 Dated : 03-10-2012 CLOSURE ORDER WITH DISCONNECTION OF ELECTRICITY WHEREAS a public complaint was received by the West Bengal Pollution Control Board (hereinafter will be referred to as the ÁState Board©), on 02-01-2012, 03-01-2012 and subsequently on 05-07-2012 against M/s. Unique Switch Gear located at 46 Madhusudan Palchowdhury 1 st Bye Lane, P.S. Howrah, Dist. Howrah, alleging noise and air pollution due to engineering and sheet metal fabrication activities with spray painting. AND WHEREAS the unit was called for hearing on 15-02-2012 by the State Board to remain present with all statutory licenses, including `Consent to Establish(NOC)/Consent to Operate' of the State Board but nobody appeared on behalf of the unit. AND WHEREAS the unit was called for hearing again on 09-04-2012 by the State Board due to its gross violation of environmental norms and this time also nobody appeared on behalf of the unit and the unit was directed to submit the copy of trade licence and NOC & Consent of State Board within 24-04-2012 positively. AND WHEREAS the unit was called for hearing again on 27-08-2012 and this time also nobody appeared on behalf of the unit. NOW THEREFORE, considering non-compliance of directions of State Board, M/s. -

Smart Border Management: Indian Coastal and Maritime Security

Contents Foreword p2/ Preface p3/ Overview p4/ Current initiatives p12/ Challenges and way forward p25/ International examples p28/Sources p32/ Glossary p36/ FICCI Security Department p38 Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security September 2017 www.pwc.in Dr Sanjaya Baru Secretary General Foreword 1 FICCI India’s long coastline presents a variety of security challenges including illegal landing of arms and explosives at isolated spots on the coast, infiltration/ex-filtration of anti-national elements, use of the sea and off shore islands for criminal activities, and smuggling of consumer and intermediate goods through sea routes. Absence of physical barriers on the coast and presence of vital industrial and defence installations near the coast also enhance the vulnerability of the coasts to illegal cross-border activities. In addition, the Indian Ocean Region is of strategic importance to India’s security. A substantial part of India’s external trade and energy supplies pass through this region. The security of India’s island territories, in particular, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, remains an important priority. Drug trafficking, sea-piracy and other clandestine activities such as gun running are emerging as new challenges to security management in the Indian Ocean region. FICCI believes that industry has the technological capability to implement border management solutions. The government could consider exploring integrated solutions provided by industry for strengthening coastal security of the country. The FICCI-PwC report on ‘Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security’ highlights the initiatives being taken by the Central and state governments to strengthen coastal security measures in the country. -

West Bengal Police Recruitment Board Araksha Bhaban, Sector – Ii, Block - Dj Salt Lake City, Kolkata – 700091

WEST BENGAL POLICE RECRUITMENT BOARD ARAKSHA BHABAN, SECTOR – II, BLOCK - DJ SALT LAKE CITY, KOLKATA – 700091 INFORMATION TO APPLICANTS FOR ‘OFF-LINE’ SUBMISSION OF APPLICATION FOR RECRUITMENT TO THE POST OF STAFF OFFICER CUM INSTRUCTOR IN CIVIL DEFENCE ORGANISATION WEST BENGAL UNDER THE DEPARTMENT OF DISASTER MANAGEMENT & CIVIL DEFENCE, GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL 1. NAME OF THE POST & PAY SCALE:- Staff Officer-cum-Instructor in Civil Defence Organisation, West Bengal under the Department of Disaster Management & Civil Defence, Govt. of West Bengal in the Pay Scale 7,100 – 37,600/- (i.e. Pay Band-3) + Grade Pay Rs. 3,600/- plus other admissible allowances. 2. NUMBER OF VACANCIES :- Staff Officer-cum-Instructor in Sl. No. Category Civil Defence Organisation, West Bengal 1. Unreserved (UR) 67 2. Scheduled Caste 28 3. Scheduled Tribe 08 4. OBC - A 13 5. OBC - B 09 TOTAL 125 NOTE : - Total vacancies as stated above is purely provisional and subject to marginal changes. 3. ELIGIBILITY :- A. The applicant must be a citizen of India. B. Educational Qualification :- The applicant must have a bachelor’s degree in any discipline from a recognized university or its equivalent. C. Language :- (i) The applicant must be able to speak, read and write Bengali Language. However, this provision will not be applicable to persons who are permanent residents of hill sub-divisions of Darjeeling and Kalimpong Districts. (ii) For applicants from hill sub-divisions of Darjeeling and Kalimpong District, the provisions laid down in the West Bengal Official language Act, 1961 will be applicable. D. AGE :- The applicant must not be below 20 years and not more than 39 years as on 01.01.2019. -

Border Security Force Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India

Border Security Force Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India RECRUITMENT OF MERITORIOUS SPORTSPERSONS TO THE POST OF CONSTABLE (GENERAL DUTY) UNDER SPORTS QUOTA 2020-21 IN BORDER SECURITY FORCE Application are invited from eligible Indian citizen (Male & Female) for filling up 269 vacancies for the Non- Gazetted & Non Ministerial post of Constable(General Duty) in Group “C” on temporary basis likely to be made permanent in Border Security Force against Sports quota as per table at Para 2(a). Application from candidate will be accepted through ON-LINE MODE only. No other mode for submission is allowed. ONLINE APPLICATION MODE WILL BE OPENED W.E.F.09/08/2021 AT 00:01 AM AND WILL BE CLOSED ON 22/09/2021 AT 11:59 PM. 2. Vacancies :- a) There are 269 vacancies in the following Sports/Games disciplines :- S/No. Name of Team Vac Nos of events/weight category 1 Boxing(Men) 49 Kg-2 52 Kg-1 56 Kg-1 60 Kg-1 10 64 Kg-1 69 Kg-1 75 Kg-1 81 Kg-1 91 + Kg-1 Boxing(Women) 10 48 Kg-1 51 Kg-1 54 Kg-1 57 Kg-1 60 Kg-1 64 Kg-1 69 Kg-1 71 Kg-1 81 Kg-1 81 + Kg-1 2 Judo(Men) 08 60 Kg-1 66 Kg-1 73 Kg-1 81 Kg-2 90 Kg-1 100 Kg-1 100 + Kg-1 Judo(Women) 08 48 Kg-1 52 Kg-1 57 Kg-1 63 Kg-1 70 Kg-1 78 Kg-1 78 + Kg-2 3 Swimming(Men) 12 Swimming Indvl Medley -1 Back stroke -1 Breast stroke -1 Butterfly Stroke -1 Free Style -1 Water polo Player-3 Golkeeper-1 Diving Spring/High board-3 Swimming(Women) 04 Water polo Player-3 Diving Spring/High board-1 4 Cross Country (Men) 02 10 KM-2 Cross Country(Women) 02 10 KM -2 5 Kabaddi (Men) 10 Raider-3 All-rounder-3 Left Corner-1 Right Corner1 Left Cover -1 Right Cover-1 6 Water Sports(Men) 10 Left-hand Canoeing-4 Right-hand Canoeing -2 Rowing -1 Kayaking -3 Water Sports(Women) 06 Canoeing -3 Kayaking -3 7 Wushu(Men) 11 48 Kg-1 52 Kg-1 56 Kg-1 60 Kg-1 65 Kg-1 70 Kg-1 75 Kg-1 80 Kg-1 85 Kg-1 90 Kg-1 90 + Kg-1 8 Gymnastics (Men) 08 All-rounder -2 Horizontal bar-2 Pommel-2 Rings-2 9 Hockey(Men) 08 Golkeeper1 Forward Attacker-2 Midfielder-3 Central Full Back-2 10 Weight Lifting(Men) 08 55 Kg-1 61 Kg-1 67 Kg-1 73 Kg-1 81 Kg-1 89 Kg-1 96 Kg-1 109 + Kg-1 Wt. -

Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban Joint Management Platform

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Stakeholderfor andAnalysis Plan Engagement Sund arban Joint ManagementarbanJoint Platform Document Information Title Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban Joint Management Platform Submitted to The World Bank Submitted by International Water Association (IWA) Contributors Bushra Nishat, AJM Zobaidur Rahman, Sushmita Mandal, Sakib Mahmud Deliverable Report on Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban description Joint Management Platform Version number Final Actual delivery date 05 April 2016 Dissemination level Members of the BISRCI Consortia Reference to be Bushra Nishat, AJM Zobaidur Rahman, Sushmita Mandal and Sakib used for citation Mahmud. Stakeholder Analysis and Engagement Plan for Sundarban Joint Management Platform (2016). International Water Association Cover picture Elderly woman pulling shrimp fry collecting nets in a river in Sundarban by AJM Zobaidur Rahman Contact Bushra Nishat, Programmes Manager South Asia, International Water Association. [email protected] Prepared for the project Bangladesh-India Sundarban Region Cooperation (BISRCI) supported by the World Bank under the South Asia Water Initiative: Sundarban Focus Area Table of Contents Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... i 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... -

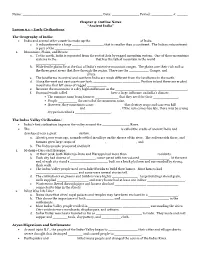

Chapter 9: Outline Notes “Ancient India” Lesson 9.1 – Early Civilizations

Name: ______________________________________ Date: _____________ Period: __________ #: _____ Chapter 9: Outline Notes “Ancient India” Lesson 9.1 – Early Civilizations The Geography of India: India and several other countries make up the _______________________ of India. o A subcontinent is a large _______________ that is smaller than a continent. The Indian subcontinent is part of the ____________. 1. Mountains, Plains, and Rivers: a. To the north, India is separated from the rest of Asia by rugged mountain system. One of these mountains systems in the __________________ that has the tallest mountain in the world ____________ ______________. b. Wide fertile plains lie at the foot of India’s extensive mountain ranges. The plains owe their rich soil to the three great rivers that flow through the region. These are the _________, Ganges, and ________________________ rivers. c. The landforms in central and southern India are much different from the landforms in the north. d. Along the west and east coasts are lush ______________ ________. Further inland there are eroded mountains that left areas of rugged _________. e. Between the mountains is a dry highland known as the ____________________ ______________. f. Seasonal winds called ____________________ have a large influence on India’s climate. The summer rains bring farmers ___________ that they need for their ____________. People _________ the arrival of the monsoon rains. However, they sometimes cause ______________ that destroy crops and can even kill _______________ and ________________. If the rain comes too late, there may be a long dry period called a _________________. The Indus Valley Civilization: India’s first civilization began in the valley around the _____________ River. -

Kolkata, Friday, 02N D February, 2018

Registered No. C604 Vol No. 02 of 2018 WEST BENGAL POLICE GAZETTE Published by Authority For departmental use only K O L K A T A , F R I D A Y , 02 N D F EBRUARY , 2018 PART - I GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL Home and Hill Affairs Department Police Establishment Branch Nabanna, 325, Sarat Chatterjee Road Mandirtala, Shibpur, From: Shri A. Sen, Howrah – 711 102 From : K. Chowdhury, Assistant Secretary to the Govt. of West Bengal. To : The Director General & Inspector General of Police, West Bengal, Bhabani Bhawan, Alipore, Kolkata – 700 027. No. 149 – PL/PB/3P-08/17 Dated : 10.01.2018 Sub. : Engagement of 55 (fifty five) Drivers on contractual basis in IB, West Bengal. The undersigned is directed to refer to his notes vide No. ORG-213/17 dated 11.10.1017 in the Secretariat File No. PB/3P-08/17 and Memo. No. 1151/ORG dated 08.08.2017 of Addl. Director General & Inspector General of Police, Establishment, West Bengal and to say that the proposal for engagement of 55 (fifty five) Drivers on contractual basis in IB, West Bengal was under active consideration of the Government for some time past. 2. Now, the undersigned is directed to say that the Governor, after careful consideration of the matter, has been pleased to accord approval for engagement of 55 (fifty five) Drivers on contractual basis in IB, West Bengal for driving the existing vehicles of IB, West Bengal. Such contractual engagement should be made purely on temporary basis only for a period of 1 (one) year at a consolidated remuneration of Rs. -

West Bengal Towards Change

West Bengal Towards Change Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation Research Foundation Published By Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation 9, Ashoka Road, New Delhi- 110001 Web :- www.spmrf.org, E-Mail: [email protected], Phone:011-23005850 Index 1. West Bengal: Towards Change 5 2. Implications of change in West Bengal 10 politics 3. BJP’s Strategy 12 4. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 14 Statements on West Bengal – excerpts 5. Statements of BJP National President 15 Amit Shah on West Bengal - excerpts 6. Corrupt Mamata Government 17 7. Anti-people Mamata government 28 8. Dictatorship of the Trinamool Congress 36 & Muzzling Dissent 9. Political Violence and Murder in West 40 Bengal 10. Trinamool Congress’s Undignified 49 Politics 11. Politics of Appeasement 52 12. Mamata Banerjee’s attack on India’s 59 federal structure 13. Benefits to West Bengal from Central 63 Government Schemes 14. West Bengal on the path of change 67 15. Select References 70 West Bengal: Towards Change West Bengal: Towards Change t is ironic that Bengal which was once one of the leading provinces of the country, radiating energy through its spiritual and cultural consciousness across India, is suffering today, caught in the grip Iof a vicious cycle of the politics of violence, appeasement and bad governance. Under Mamata Banerjee’s regime, unrest and distrust defines and dominates the atmosphere in the state. There is a no sphere, be it political, social or religious which is today free from violence and instability. It is well known that from this very land of Bengal, Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore had given the message of peace and unity to the whole world by establishing Visva Bharati at Santiniketan. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

Over the Years

Over the Years Indra Rai Sharma Over the Years -A Photo Autobiography In 2010 before going to US, I had been going through my old papers. As it appeared, I had wished to pen down my autobiography long back. In my diary on February 10, 1963, I had written that if I would ever write my autobiography, I would caption it ‘My Life and Dreams’. In 1997 again, in my acceptance letter to the notice regarding my impending retirement that I sent on June 23, to Mr. A. Sankara Narayanan, Executive Director, M/S Hindustan Motors, I wrote: “I wish I could pen down my years at HM some day and hope that it would provide useful insight for our budding engineers as Lee Iacocca’s biography or the book ’On a clear day you can see General Motors’ provided to millions of it readers.’ I knew that I was not that great a name in HM or industry, though I aspired to be one. Perhaps I didn’t select the right profession or I couldn’t take advantage of the opportunity that I got to convert the same to become big. I remember my teasing of my grandmother and later on my mother in school days by telling them time and again that they should not expect me to do routine household work, as I would be a big man. Later on I joked with some close friends and their wives that one day I would get into number 1 Rajpath. I meant Rastrapati Bhawan. I failed to become as great or big as I wanted but I did work very hard for every assignment that I got.