Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy: Latest Evidence & Future Directions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vaccination Certificate Information Version: 21 July 2021

معلومات عن شهادة التطعيم، بالعربية 中文疫苗接种凭证信息 Informations sur le certificat de vaccination en FRANÇAIS Информация о сертификате вакцинации на РУССКОМ ЯЗЫКЕ Información sobre el Certificado de Vacunación en ESPAÑOL UN SYSTEM-WIDE COVID-19 VACCINATION PROGRAMME VACCINATION CERTIFICATE INFORMATION VERSION: 21 JULY 2021 ABOUT THE UN SYSTEM-WIDE COVID-19 VACCINATION PROGRAMME The UN is committed to ensuring the protection of its personnel. Tasked by the Secretary-General, the Department of Operational Support (DOS) is leading a coordinated, UN-system-wide effort to ensure the availability of vaccine to UN personnel, their dependents and implementing partners. The roll-out of the UN System-wide COVID-19 Vaccination Programme (the “Programme”) for UN personnel will provide a significant boost to the ability of personnel to stay and deliver on the Organization's mandates, to support beneficiaries in the communities they serve, and to contribute to our on-going work to recover better together from the pandemic. Information about the Programme is available at: https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/vaccination ABOUT THE VACCINATION CERTIFICATE Upon administration of the requisite vaccine dosage, a certificate of vaccination is generated through the Programme’s registration platform (the “Platform”). The certificate generated by the Platform uses a standardized format, similar to the one used by the WHO in its “International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis” (Yellow) vaccination booklet. Note: This certificate may not dispense with travel restrictions put in place by the country(ies) of destination. As the nature of the pandemic continues to rapidly evolve, it is highly advisable to check the latest travel regulations. -

Global Dynamics of a Vaccination Model for Infectious Diseases with Asymptomatic Carriers

MATHEMATICAL BIOSCIENCES doi:10.3934/mbe.2016019 AND ENGINEERING Volume 13, Number 4, August 2016 pp. 813{840 GLOBAL DYNAMICS OF A VACCINATION MODEL FOR INFECTIOUS DISEASES WITH ASYMPTOMATIC CARRIERS Martin Luther Mann Manyombe1;2 and Joseph Mbang1;2 Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science University of Yaounde 1, P.O. Box 812 Yaounde, Cameroon 1;2;3; Jean Lubuma and Berge Tsanou ∗ Department of Mathematics and Applied Mathematics University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0002, South Africa (Communicated by Abba Gumel) Abstract. In this paper, an epidemic model is investigated for infectious dis- eases that can be transmitted through both the infectious individuals and the asymptomatic carriers (i.e., infected individuals who are contagious but do not show any disease symptoms). We propose a dose-structured vaccination model with multiple transmission pathways. Based on the range of the explic- itly computed basic reproduction number, we prove the global stability of the disease-free when this threshold number is less or equal to the unity. Moreover, whenever it is greater than one, the existence of the unique endemic equilibrium is shown and its global stability is established for the case where the changes of displaying the disease symptoms are independent of the vulnerable classes. Further, the model is shown to exhibit a transcritical bifurcation with the unit basic reproduction number being the bifurcation parameter. The impacts of the asymptomatic carriers and the effectiveness of vaccination on the disease transmission are discussed through through the local and the global sensitivity analyses of the basic reproduction number. Finally, a case study of hepatitis B virus disease (HBV) is considered, with the numerical simulations presented to support the analytical results. -

The Hepatitis B Vaccine Is the Most Widely Used Vaccine in the World, with Over 1 Billion Doses Given

Hepatitis B Vaccine Protect Yourself and Those You Love What is Hepatitis B? Hepatitis B is the most common serious liver infection in the world. It is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), which attacks liver cells and can lead to liver failure, cirrhosis (scarring), or liver cancer later in life. The virus is transmitted through direct contact with infected blood and bodily fluids, and from an infected woman to her newborn at birth. Is there a safe vaccine for hepatitis B? YES! The good news is that there is a safe and effective vaccine for hepatitis B. The vaccine is a series, typically given as three shots over a six-month period that will provide a lifetime of protection. You cannot get hepatitis B from the vaccine – there is no human blood or live virus in the vaccine. The hepatitis B vaccine is the most widely used vaccine in the world, with over 1 billion doses given. The hepatitis B vaccine is the first "anti-cancer" vaccine because it can help prevent liver cancer! Who should be vaccinated against hepatitis B? The World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend the hepatitis B vaccine for all newborns and children up to 18 years of age, and all high-risk adults. All infants should receive the first dose of the vaccine in the delivery room or in the first 24 hours of life, preferably within 12 hours. (CDC recommends the first dose within 12 hours vs. the WHO recommendation of 24 hours.) The HBV vaccine is recommended to anyone who is at high risk of infection. -

Vaccinator Training Plan Workstream 4: Vaccine Process and Workforce Subgroup 3: Workforce Planning and Training

Vaccinator Training Plan Workstream 4: Vaccine Process and Workforce Subgroup 3: Workforce Planning and Training Health Service Executive Vaccinator Training Plan COVID-19 Vaccination Programme Subgroup 3: Workforce Planning and Prepared by Training [New Vaccinator Working Group] David Walsh, Workstream Lead Approved by Vaccination Process and Workforce Date 15th April2021 Version 02 1 Vaccinator Training Plan Workstream 4: Vaccine Process and Workforce Subgroup 3: Workforce Planning and Training Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope of the Training Programme .................................................................................................................. 3 Training Programme Delivery Approach ........................................................................................................ 6 Develop Training Programmes.................................................................................................................... 6 Deliver Vaccinator Training ......................................................................................................................... 7 Delivering the Training .................................................................................................................................... 9 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... -

Vaccine Hesitancy

WHY CHILDREN WORKSHOP ON IMMUNIZATIONS ARE NOT VACCINATED? VACCINE HESITANCY José Esparza MD, PhD - Adjunct Professor, Institute of Human Virology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA - Robert Koch Fellow, Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany - Senior Advisor, Global Virus Network, Baltimore, MD, USA. Formerly: - Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, WA, USA - World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland The value of vaccination “The impact of vaccination on the health of the world’s people is hard to exaggerate. With the exception of safe water, no other modality has had such a major effect on mortality reduction and population growth” Stanley Plotkin (2013) VACCINES VAILABLE TO PROTECT AGAINST MORE DISEASES (US) BASIC VACCINES RECOMMENDED BY WHO For all: BCG, hepatitis B, polio, DTP, Hib, Pneumococcal (conjugated), rotavirus, measles, rubella, HPV. For certain regions: Japanese encephalitis, yellow fever, tick-borne encephalitis. For some high-risk populations: typhoid, cholera, meningococcal, hepatitis A, rabies. For certain immunization programs: mumps, influenza Vaccines save millions of lives annually, worldwide WHAT THE WORLD HAS ACHIEVED: 40 YEARS OF INCREASING REACH OF BASIC VACCINES “Bill Gates Chart” 17 M GAVI 5.6 M 4.2 M Today (ca 2015): <5% of children in GAVI countries fully immunised with the 11 WHO- recommended vaccines Seth Berkley (GAVI) The goal: 50% of children in GAVI countries fully immunised by 2020 Seth Berkley (GAVI) The current world immunization efforts are achieving: • Equity between high and low-income countries • Bringing the power of vaccines to even the world’s poorest countries • Reducing morbidity and mortality in developing countries • Eliminating and eradicating disease WHY CHILDREN ARE NOT VACCINATED? •Vaccines are not available •Deficient health care systems •Poverty •Vaccine hesitancy (reticencia a la vacunacion) VACCINE HESITANCE: WHO DEFINITION “Vaccine hesitancy refers to delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services. -

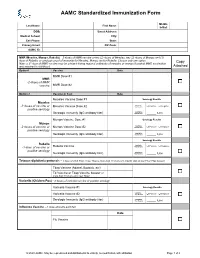

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form Middle Last Name: First Name: Initial: DOB: Street Address: Medical School: City: Cell Phone: State: Primary Email: ZIP Code: AAMC ID: MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella) – 2 doses of MMR vaccine or two (2) doses of Measles, two (2) doses of Mumps and (1) dose of Rubella; or serologic proof of immunity for Measles, Mumps and/or Rubella. Choose only one option. Copy Note: a 3rd dose of MMR vaccine may be advised during regional outbreaks of measles or mumps if original MMR vaccination was received in childhood. Attached Option1 Vaccine Date MMR Dose #1 MMR -2 doses of MMR vaccine MMR Dose #2 Option 2 Vaccine or Test Date Measles Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Measles Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Measles Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Mumps Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Mumps Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Mumps Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Serology Results Rubella Qualitative Positive Negative -1 dose of vaccine or Rubella Vaccine Titer Results: positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis – 1 dose of adult Tdap; if last Tdap is more than 10 years old, provide date of last Td or Tdap booster Tdap Vaccine (Adacel, Boostrix, etc) Td Vaccine or Tdap Vaccine booster (if more than 10 years since last Tdap) Varicella (Chicken Pox) - 2 doses of varicella vaccine or positive serology Varicella Vaccine #1 Serology Results Qualitative Varicella Vaccine #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Quantitative Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Influenza Vaccine --1 dose annually each fall Date Flu Vaccine © 2020 AAMC. -

Hepatitis B Vaccine – Frequently Asked Questions (Information from the CDC)

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form 2020 Hepatitis B Vaccine – Frequently Asked Questions (Information from the CDC) 1. What are the hepatitis B vaccines licensed for use in the United States? Three single-antigen vaccines and two combination vaccines are currently licensed in the United States. Single-antigen hepatitis B vaccines: • ENGERIX-B® • RECOMBIVAX HB® • HEPLISAV-B™ Combination vaccines: • PEDIARIX®: Combined hepatitis B, diphtheria, tetanus, acellular pertussis (DTaP), and inactivated poliovirus (IPV) vaccine. Cannot be administered before age 6 weeks or after age 7 years. • TWINRIX®: Combined Hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccine. Recommended for people aged ≥18 years who are at increased risk for both HAV and HBV infections. 2. What are the recommended schedules for hepatitis B vaccination? The vaccination schedule most often used for children and adults is three doses given at 0, 1, and 6 months. Alternate schedules have been approved for certain vaccines and/or populations. A new formulation, Heplisav-B (HepB-CpG), is approved to be given as two doses one month apart. 3. If there is an interruption between doses of hepatitis B vaccine, does the vaccine series need to be restarted? No. The series does not need to be restarted but the following should be considered: • If the vaccine series was interrupted after the first dose, the second dose should be administered as soon as possible. • The second and third doses should be separated by an interval of at least 8 weeks. • If only the third dose is delayed, it should be administered as soon as possible. 4. Is it harmful to administer an extra dose of hepatitis B vaccine or to repeat the entire vaccine series if documentation of the vaccination history is unavailable or the serology test is negative? No, administering extra doses of single-antigen hepatitis B vaccine is not harmful. -

Statements Contained in This Release As the Result of New Information Or Future Events Or Developments

Pfizer and BioNTech Provide Update on Booster Program in Light of the Delta-Variant NEW YORK and MAINZ, GERMANY, July 8, 2021 — As part of Pfizer’s and BioNTech’s continued efforts to stay ahead of the virus causing COVID-19 and circulating mutations, the companies are providing an update on their comprehensive booster strategy. Pfizer and BioNTech have seen encouraging data in the ongoing booster trial of a third dose of the current BNT162b2 vaccine. Initial data from the study demonstrate that a booster dose given 6 months after the second dose has a consistent tolerability profile while eliciting high neutralization titers against the wild type and the Beta variant, which are 5 to 10 times higher than after two primary doses. The companies expect to publish more definitive data soon as well as in a peer-reviewed journal and plan to submit the data to the FDA, EMA and other regulatory authorities in the coming weeks. In addition, data from a recent Nature paper demonstrate that immune sera obtained shortly after dose 2 of the primary two dose series of BNT162b2 have strong neutralization titers against the Delta variant (B.1.617.2 lineage) in laboratory tests. The companies anticipate that a third dose will boost those antibody titers even higher, similar to how the third dose performs for the Beta variant (B.1.351). Pfizer and BioNTech are conducting preclinical and clinical tests to confirm this hypothesis. While Pfizer and BioNTech believe a third dose of BNT162b2 has the potential to preserve the highest levels of protective efficacy against all currently known variants including Delta, the companies are remaining vigilant and are developing an updated version of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine that targets the full spike protein of the Delta variant. -

COVID-19 Vaccines Frequently Asked Questions

Page 1 of 12 COVID-19 Vaccines 2020a Frequently Asked Questions Michigan.gov/Coronavirus The information in this document will change frequently as we learn more about COVID-19 vaccines. There is a lot we are learning as the pandemic and COVID-19 vaccines evolve. The approach in Michigan will adapt as we learn more. September 29, 2021. Quick Links What’s new | Why COVID-19 vaccination is important | Booster and additional doses | What to expect when you get vaccinated | Safety of the vaccine | Vaccine distribution/prioritization | Additional vaccine information | Protecting your privacy | Where can I get more information? What’s new − Pfizer booster doses recommended for some people to boost waning immunity six months after completing the Pfizer vaccine. Why COVID-19 vaccination is important − If you are fully vaccinated, you don’t have to quarantine after being exposed to COVID-19, as long as you don’t have symptoms. This means missing less work, school, sports and other activities. − COVID-19 vaccination is the safest way to build protection. COVID-19 is still a threat, especially to people who are unvaccinated. Some people who get COVID-19 can become severely ill, which could result in hospitalization, and some people have ongoing health problems several weeks or even longer after getting infected. Even people who did not have symptoms when they were infected can have these ongoing health problems. − After you are fully vaccinated for COVID-19, you can resume many activities that you did before the pandemic. CDC recommends that fully vaccinated people wear a mask in public indoor settings if they are in an area of substantial or high transmission. -

Vaccinator Required Pre-Clinic Training

Vaccinator required pre-clinic training Training (click title to be directed to training PDF or website) Type of Training Page number POD Vaccination Clinic Overview PDF 2 POD Role Description PDF 18 Complete COVID-19 Vaccine Training: General Overview of Web training Web Immunization Best Practices for Healthcare Providers Moderna - CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccine: What Healthcare Web training Web Professionals Need to Know Moderna’s EUA Factsheet for providers PDF 23 Moderna’s EUA Factsheet for recipients PDF 45 Review of information on Moderna’s website Webpage Web Review of CDC’s information on Moderna vaccine Webpage Web Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine; Vaccine Preparation and Webpage Web Administration Summary Pfizer - CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccine: What Healthcare Professionals Web training Web Need to Know Pfizer’s EUA Factsheet for providers PDF 50 Pfizer’s EUA Factsheet for recipients PDF 80 Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine; Vaccine Preparation and Webpage Web Administration Summary Review CDC’s information on Pfizer’s vaccine Webpage Web Health Department’s Immunization Protocol PDF 86 Health Department’s Medical Orders for COVID-19 Vaccines PDF 89 Health Department’s Bloodborne Pathogen Plan and Appendices PDF 93 2, 4, 5 & 6 Health Department’s Emergency Care and Adverse Event PDF 111 Guidelines Health Department’s Epinephrine Medical Order PDF 116 VAMS Sheet for Healthcare Providers and video attached to email PDF 118 When I Work Training PDF 119 Agency of Human Services HIPAA Awareness Training PDF 132 Review CDC’s Interim Considerations: Preparing -

Immunogenicity and Safety of a Third Dose, and Immune Persistence Of

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.23.21261026; this version posted July 25, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Immunogenicity and safety of a third dose, and immune persistence of 2 CoronaVac vaccine in healthy adults aged 18-59 years: interim results 3 from a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical 4 trial 5 6 Hongxing Pan MSc1*, Qianhui Wu MPH2*, Gang Zeng Ph.D.3*, Juan Yang Ph.D.1, Deyu 7 Jiang MSc4, Xiaowei Deng MSc2, Kai Chu MSc1, Wen Zheng BSc2, Fengcai Zhu M.D.5†, 8 Hongjie Yu M.D. Ph.D.2,6,7†, Weidong Yin MBA8† 9 10 Affiliations 11 1. Vaccine Evaluation Institute, Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and 12 Prevention, Nanjing, China 13 2. School of Public Health, Fudan University, Key Laboratory of Public Health Safety, 14 Ministry of Education, Shanghai, China 15 3. Clinical Research Department, Sinovac Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China 16 4. Covid-19 Vaccine Department, Sinovac Life Sciences Co., Ltd., Beijing, China 17 5. Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Nanjing, China 18 6. Shanghai Institute of Infectious Disease and Biosecurity, Fudan University, 19 Shanghai, China 20 7. Department of Infectious Diseases, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, 21 Shanghai, China 22 8. Sinovac Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. -

Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule

Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule UNITED STATES for ages 19 years or older 2021 Recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices How to use the adult immunization schedule (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip) and approved by the Centers for Disease Determine recommended Assess need for additional Review vaccine types, Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov), American College of Physicians 1 vaccinations by age 2 recommended vaccinations 3 frequencies, and intervals (www.acponline.org), American Academy of Family Physicians (www.aafp. (Table 1) by medical condition and and considerations for org), American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (www.acog.org), other indications (Table 2) special situations (Notes) American College of Nurse-Midwives (www.midwife.org), and American Academy of Physician Assistants (www.aapa.org). Vaccines in the Adult Immunization Schedule* Report y Vaccines Abbreviations Trade names Suspected cases of reportable vaccine-preventable diseases or outbreaks to the local or state health department Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine Hib ActHIB® y Clinically significant postvaccination reactions to the Vaccine Adverse Event Hiberix® Reporting System at www.vaers.hhs.gov or 800-822-7967 PedvaxHIB® Hepatitis A vaccine HepA Havrix® Injury claims Vaqta® All vaccines included in the adult immunization schedule except pneumococcal 23-valent polysaccharide (PPSV23) and zoster (RZV) vaccines are covered by the Hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccine HepA-HepB Twinrix® Vaccine Injury Compensation Program. Information on how to file a vaccine injury Hepatitis B vaccine HepB Engerix-B® claim is available at www.hrsa.gov/vaccinecompensation. Recombivax HB® Heplisav-B® Questions or comments Contact www.cdc.gov/cdc-info or 800-CDC-INFO (800-232-4636), in English or Human papillomavirus vaccine HPV Gardasil 9® Spanish, 8 a.m.–8 p.m.