Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy: Implications for COVID-19 Public Health Messaging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Evaluation Key Outcomes and Addressing Remaining

Vaccine 31S (2013) J73–J78 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Vaccine jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vaccine Key outcomes and addressing remaining challenges—Perspectives from a final ଝ evaluation of the China GAVI project a,1 a,1 a,1 a,1 b c Weizhong Yang , Xiaofeng Liang , Fuqiang Cui , Li Li , Stephen C. Hadler , Yvan J. Hutin , d a,∗ Mark Kane , Yu Wang a Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, China b Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA c Europe Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Stockholm, Sweden d Mercer Island, Washington, USA a r t a b i c s t l r e i n f o a c t Article history: During the China GAVI project, implemented between 2002 and 2010, more than 25 million children Received 6 June 2012 received hepatitis B vaccine with the support of project, and the vaccine proved to be safe and effective. Received in revised form 24 July 2012 With careful consideration for project savings, China and GAVI continually adjusted the budget, addi- Accepted 24 September 2012 tionally allowing the project to spend operational funds to support demonstration projects to improve timely birth dose (TBD), conduct training of EPI staff, and to monitor the project impact. Results from the final evaluation indicated the achievement of key outcomes. As a result of government co-investment, Keywords: human resources at county level engaged in hepatitis B vaccination increased from 29 per county on GAVI Project average in 2002 to 66 in 2009. All project counties funded by the GAVI project use auto-disable syringes Outcomes for hepatitis B vaccination and other vaccines. -

Vaccination Certificate Information Version: 21 July 2021

معلومات عن شهادة التطعيم، بالعربية 中文疫苗接种凭证信息 Informations sur le certificat de vaccination en FRANÇAIS Информация о сертификате вакцинации на РУССКОМ ЯЗЫКЕ Información sobre el Certificado de Vacunación en ESPAÑOL UN SYSTEM-WIDE COVID-19 VACCINATION PROGRAMME VACCINATION CERTIFICATE INFORMATION VERSION: 21 JULY 2021 ABOUT THE UN SYSTEM-WIDE COVID-19 VACCINATION PROGRAMME The UN is committed to ensuring the protection of its personnel. Tasked by the Secretary-General, the Department of Operational Support (DOS) is leading a coordinated, UN-system-wide effort to ensure the availability of vaccine to UN personnel, their dependents and implementing partners. The roll-out of the UN System-wide COVID-19 Vaccination Programme (the “Programme”) for UN personnel will provide a significant boost to the ability of personnel to stay and deliver on the Organization's mandates, to support beneficiaries in the communities they serve, and to contribute to our on-going work to recover better together from the pandemic. Information about the Programme is available at: https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/vaccination ABOUT THE VACCINATION CERTIFICATE Upon administration of the requisite vaccine dosage, a certificate of vaccination is generated through the Programme’s registration platform (the “Platform”). The certificate generated by the Platform uses a standardized format, similar to the one used by the WHO in its “International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis” (Yellow) vaccination booklet. Note: This certificate may not dispense with travel restrictions put in place by the country(ies) of destination. As the nature of the pandemic continues to rapidly evolve, it is highly advisable to check the latest travel regulations. -

Global Dynamics of a Vaccination Model for Infectious Diseases with Asymptomatic Carriers

MATHEMATICAL BIOSCIENCES doi:10.3934/mbe.2016019 AND ENGINEERING Volume 13, Number 4, August 2016 pp. 813{840 GLOBAL DYNAMICS OF A VACCINATION MODEL FOR INFECTIOUS DISEASES WITH ASYMPTOMATIC CARRIERS Martin Luther Mann Manyombe1;2 and Joseph Mbang1;2 Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science University of Yaounde 1, P.O. Box 812 Yaounde, Cameroon 1;2;3; Jean Lubuma and Berge Tsanou ∗ Department of Mathematics and Applied Mathematics University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0002, South Africa (Communicated by Abba Gumel) Abstract. In this paper, an epidemic model is investigated for infectious dis- eases that can be transmitted through both the infectious individuals and the asymptomatic carriers (i.e., infected individuals who are contagious but do not show any disease symptoms). We propose a dose-structured vaccination model with multiple transmission pathways. Based on the range of the explic- itly computed basic reproduction number, we prove the global stability of the disease-free when this threshold number is less or equal to the unity. Moreover, whenever it is greater than one, the existence of the unique endemic equilibrium is shown and its global stability is established for the case where the changes of displaying the disease symptoms are independent of the vulnerable classes. Further, the model is shown to exhibit a transcritical bifurcation with the unit basic reproduction number being the bifurcation parameter. The impacts of the asymptomatic carriers and the effectiveness of vaccination on the disease transmission are discussed through through the local and the global sensitivity analyses of the basic reproduction number. Finally, a case study of hepatitis B virus disease (HBV) is considered, with the numerical simulations presented to support the analytical results. -

UNHCR COVID-19 Global Emergency Response

GLOBAL COVID-19 EMERGENCY RESPONSE 17 February 2021 UNHCR COVID-19 Preparedness and Response Highlights COVID-19 update ■ UNHCR and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, signed a Memorandum of Over 46,000 Understanding (MoU) on 03 February 2020, with the overall goal of ensuring reported cases refugees and other forcibly displaced can access vaccines on par with of COVID-19 nationals. The MoU also looks at expanding coverage and quality of among forcibly displaced people immunization services, promoting equity in access and uptake of vaccines, and strengthening health systems at community and primary care level. across 103 countries ■ Jordan has become one of the world’s first countries to start COVID-19 vaccinations for refugees, including vaccinations in Za’atari refugee camp on 15 February. UNHCR has been working with the Jordanian government to increase of vaccinate refugees and provide critical health, sanitation, hygiene and logistical some 7,500 cases compared support. UNHCR appeals to all countries to follow suit and include refugees in to the previous their national vaccination drives in line with COVAX allocation principles. reporting period ■ In 2020, 39.4 million persons of concern received COVID-19 assistance (numbers as of 08 February including access to protection services, shelter, health, and education. This 2021) includes over 8.5 million individuals who received cash assistance. ■ Despite an estimated 1.44 million refugees in urgent need of resettlement globally, less than 23,000 were resettled through UNHCR last year. These are the lowest refugee resettlement numbers UNHCR has witnessed in almost two decades. The drop stems from low quotas put forward by states, as well as the impact of COVID-19, which delayed departures and programmes. -

Vaccine Hesitancy

WHY CHILDREN WORKSHOP ON IMMUNIZATIONS ARE NOT VACCINATED? VACCINE HESITANCY José Esparza MD, PhD - Adjunct Professor, Institute of Human Virology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA - Robert Koch Fellow, Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany - Senior Advisor, Global Virus Network, Baltimore, MD, USA. Formerly: - Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Seattle, WA, USA - World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland The value of vaccination “The impact of vaccination on the health of the world’s people is hard to exaggerate. With the exception of safe water, no other modality has had such a major effect on mortality reduction and population growth” Stanley Plotkin (2013) VACCINES VAILABLE TO PROTECT AGAINST MORE DISEASES (US) BASIC VACCINES RECOMMENDED BY WHO For all: BCG, hepatitis B, polio, DTP, Hib, Pneumococcal (conjugated), rotavirus, measles, rubella, HPV. For certain regions: Japanese encephalitis, yellow fever, tick-borne encephalitis. For some high-risk populations: typhoid, cholera, meningococcal, hepatitis A, rabies. For certain immunization programs: mumps, influenza Vaccines save millions of lives annually, worldwide WHAT THE WORLD HAS ACHIEVED: 40 YEARS OF INCREASING REACH OF BASIC VACCINES “Bill Gates Chart” 17 M GAVI 5.6 M 4.2 M Today (ca 2015): <5% of children in GAVI countries fully immunised with the 11 WHO- recommended vaccines Seth Berkley (GAVI) The goal: 50% of children in GAVI countries fully immunised by 2020 Seth Berkley (GAVI) The current world immunization efforts are achieving: • Equity between high and low-income countries • Bringing the power of vaccines to even the world’s poorest countries • Reducing morbidity and mortality in developing countries • Eliminating and eradicating disease WHY CHILDREN ARE NOT VACCINATED? •Vaccines are not available •Deficient health care systems •Poverty •Vaccine hesitancy (reticencia a la vacunacion) VACCINE HESITANCE: WHO DEFINITION “Vaccine hesitancy refers to delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services. -

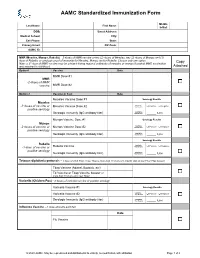

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form

AAMC Standardized Immunization Form Middle Last Name: First Name: Initial: DOB: Street Address: Medical School: City: Cell Phone: State: Primary Email: ZIP Code: AAMC ID: MMR (Measles, Mumps, Rubella) – 2 doses of MMR vaccine or two (2) doses of Measles, two (2) doses of Mumps and (1) dose of Rubella; or serologic proof of immunity for Measles, Mumps and/or Rubella. Choose only one option. Copy Note: a 3rd dose of MMR vaccine may be advised during regional outbreaks of measles or mumps if original MMR vaccination was received in childhood. Attached Option1 Vaccine Date MMR Dose #1 MMR -2 doses of MMR vaccine MMR Dose #2 Option 2 Vaccine or Test Date Measles Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Measles Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Measles Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Mumps Vaccine Dose #1 Serology Results Mumps Qualitative -2 doses of vaccine or Mumps Vaccine Dose #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Serology Results Rubella Qualitative Positive Negative -1 dose of vaccine or Rubella Vaccine Titer Results: positive serology Quantitative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis – 1 dose of adult Tdap; if last Tdap is more than 10 years old, provide date of last Td or Tdap booster Tdap Vaccine (Adacel, Boostrix, etc) Td Vaccine or Tdap Vaccine booster (if more than 10 years since last Tdap) Varicella (Chicken Pox) - 2 doses of varicella vaccine or positive serology Varicella Vaccine #1 Serology Results Qualitative Varicella Vaccine #2 Titer Results: Positive Negative Serologic Immunity (IgG antibody titer) Quantitative Titer Results: _____ IU/ml Influenza Vaccine --1 dose annually each fall Date Flu Vaccine © 2020 AAMC. -

Statements Contained in This Release As the Result of New Information Or Future Events Or Developments

Pfizer and BioNTech Provide Update on Booster Program in Light of the Delta-Variant NEW YORK and MAINZ, GERMANY, July 8, 2021 — As part of Pfizer’s and BioNTech’s continued efforts to stay ahead of the virus causing COVID-19 and circulating mutations, the companies are providing an update on their comprehensive booster strategy. Pfizer and BioNTech have seen encouraging data in the ongoing booster trial of a third dose of the current BNT162b2 vaccine. Initial data from the study demonstrate that a booster dose given 6 months after the second dose has a consistent tolerability profile while eliciting high neutralization titers against the wild type and the Beta variant, which are 5 to 10 times higher than after two primary doses. The companies expect to publish more definitive data soon as well as in a peer-reviewed journal and plan to submit the data to the FDA, EMA and other regulatory authorities in the coming weeks. In addition, data from a recent Nature paper demonstrate that immune sera obtained shortly after dose 2 of the primary two dose series of BNT162b2 have strong neutralization titers against the Delta variant (B.1.617.2 lineage) in laboratory tests. The companies anticipate that a third dose will boost those antibody titers even higher, similar to how the third dose performs for the Beta variant (B.1.351). Pfizer and BioNTech are conducting preclinical and clinical tests to confirm this hypothesis. While Pfizer and BioNTech believe a third dose of BNT162b2 has the potential to preserve the highest levels of protective efficacy against all currently known variants including Delta, the companies are remaining vigilant and are developing an updated version of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine that targets the full spike protein of the Delta variant. -

COVID-19 Vaccines Frequently Asked Questions

Page 1 of 12 COVID-19 Vaccines 2020a Frequently Asked Questions Michigan.gov/Coronavirus The information in this document will change frequently as we learn more about COVID-19 vaccines. There is a lot we are learning as the pandemic and COVID-19 vaccines evolve. The approach in Michigan will adapt as we learn more. September 29, 2021. Quick Links What’s new | Why COVID-19 vaccination is important | Booster and additional doses | What to expect when you get vaccinated | Safety of the vaccine | Vaccine distribution/prioritization | Additional vaccine information | Protecting your privacy | Where can I get more information? What’s new − Pfizer booster doses recommended for some people to boost waning immunity six months after completing the Pfizer vaccine. Why COVID-19 vaccination is important − If you are fully vaccinated, you don’t have to quarantine after being exposed to COVID-19, as long as you don’t have symptoms. This means missing less work, school, sports and other activities. − COVID-19 vaccination is the safest way to build protection. COVID-19 is still a threat, especially to people who are unvaccinated. Some people who get COVID-19 can become severely ill, which could result in hospitalization, and some people have ongoing health problems several weeks or even longer after getting infected. Even people who did not have symptoms when they were infected can have these ongoing health problems. − After you are fully vaccinated for COVID-19, you can resume many activities that you did before the pandemic. CDC recommends that fully vaccinated people wear a mask in public indoor settings if they are in an area of substantial or high transmission. -

Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule

Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule UNITED STATES for ages 19 years or older 2021 Recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices How to use the adult immunization schedule (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip) and approved by the Centers for Disease Determine recommended Assess need for additional Review vaccine types, Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov), American College of Physicians 1 vaccinations by age 2 recommended vaccinations 3 frequencies, and intervals (www.acponline.org), American Academy of Family Physicians (www.aafp. (Table 1) by medical condition and and considerations for org), American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (www.acog.org), other indications (Table 2) special situations (Notes) American College of Nurse-Midwives (www.midwife.org), and American Academy of Physician Assistants (www.aapa.org). Vaccines in the Adult Immunization Schedule* Report y Vaccines Abbreviations Trade names Suspected cases of reportable vaccine-preventable diseases or outbreaks to the local or state health department Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine Hib ActHIB® y Clinically significant postvaccination reactions to the Vaccine Adverse Event Hiberix® Reporting System at www.vaers.hhs.gov or 800-822-7967 PedvaxHIB® Hepatitis A vaccine HepA Havrix® Injury claims Vaqta® All vaccines included in the adult immunization schedule except pneumococcal 23-valent polysaccharide (PPSV23) and zoster (RZV) vaccines are covered by the Hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccine HepA-HepB Twinrix® Vaccine Injury Compensation Program. Information on how to file a vaccine injury Hepatitis B vaccine HepB Engerix-B® claim is available at www.hrsa.gov/vaccinecompensation. Recombivax HB® Heplisav-B® Questions or comments Contact www.cdc.gov/cdc-info or 800-CDC-INFO (800-232-4636), in English or Human papillomavirus vaccine HPV Gardasil 9® Spanish, 8 a.m.–8 p.m. -

The Mississippi Covid-19 Vaccine Confidence Survey: Population Results Report

MAY 2021 THE MISSISSIPPI COVID-19 VACCINE CONFIDENCE SURVEY: POPULATION RESULTS Report A collaborative population-based study The Mississippi Community Engagement Alliance Against COVID-19 Disparities (CEAL) Team The Mississippi State Department of Health: Office of Preventive Health and Health Equity EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Since the Spring of 2020, the Novel 2019 Office of Preventive Health and Health Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic has Equity (OPHHE) disseminated a statewide impacted Mississippians of every race, vaccine confidence survey beginning end ethnicity, age, gender, and income bracket. of December 2020 and collecting data Unfortunately, it has disproportionately until March 2021. The survey is intended to impacted Mississippians of color, the elderly, be representative of Mississippians, with and those living with chronic disease. For intentional efforts invested to reach lower most of the past year, the State has worked income and rural Mississippi populations, as to protect its population through preventive well as the state’s Black, Hispanic (Latino/ measures such as social distancing and Latinx), Asian (including the Vietnamese personal protective equipment. However, population of the Gulf Coast), and Native with the release of COVID-19 Vaccines to American/Choctaw communities. The sur- the public, the population of Mississippi has vey was administered in three languages- the opportunity to embrace a long-term English, Spanish, and Vietnamese- through a solution to COVID-19. That is, if Mississippians mixed-modal survey effort, including: web- are willing to receive the vaccine. To based, paper-based, and verbal-oratory assess Mississippians’ COVID-19 Vaccine administration. All targeted populations confidence, the Mississippi Community were ultimately reached and are represented Engagement Alliance Against COVID-19 in the over 11,000 completed responses Disparities (CEAL) Team and the Mississippi from all 82 of Mississippi’s counties. -

Parental Attitudes About Sexually Transmitted Infection Vaccination for Their Adolescent Children

ARTICLE Parental Attitudes About Sexually Transmitted Infection Vaccination for Their Adolescent Children Gregory D. Zimet, PhD; Rose M. Mays, RN, PhD; Lynne A. Sturm, PhD; April A. Ravert, MS; Susan M. Perkins, PhD; Beth E. Juliar, MA, MS Objectives: To evaluate parental attitudes about adoles- Results: The mean vaccine scenario rating was 81.3. Sexu- cent vaccination as a function of vaccine characteristics, in- ally transmitted infection vaccines (mean, 81.3) were not cluding whether the vaccine prevented a sexually transmit- rated differently than non-STI vaccines (mean, 80.0). Con- tedinfection(STI),andtoexplorepossiblesociodemographic joint analysis indicated that severity of infection and vac- predictors of acceptability of STI vaccines. cine efficacy had the strongest influence on ratings, fol- lowed by availability of behavioral prevention. Mode of Design: Participants were 278 parents who accompa- transmission had a negligible effect on ratings. Child age nied their children (69.1% female, aged 12-17 years) to (P=.08) and sex (P=.77), parent age (P=.32) and educa- appointments at medical clinics. By using computer- tion (P=.34), insurance status (P=.08), and data collection based questionnaires, parents rated 9 hypothetical vac- site (P=.48) were not significantly associated with STI vac- cine scenarios, each of which was defined along 4 di- cine acceptability. mensions: mode of transmission (STI or non-STI), severity Conclusions: Parents were accepting of the idea of vac- of infection (curable, chronic, or fatal), vaccine efficacy cinating their adolescent children against STIs. The most (50%, 70%, or 90%), and availability of behavioral meth- salient issues were severity of infection and vaccine ef- ods for prevention (available or not available). -

Improving Vaccination Coverage Fact Sheet

Improving Vaccination Coverage Fact Sheet Improving Vaccination Coverage for Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Public confidence in immunization is critical to sustaining and increasing vaccination coverage rates and preventing outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases (VPDs). There is some evidence suggesting vaccination requirements that have broad reach, limited exemption criteria, and strong enforcement may help promote higher rates of vaccination coverage along with complementary actions such as monitoring VPD cases, vaccination coverage, and exemption rates; and also reporting on recent VPD outbreaks. Importation of measles into the U.S. emphasizes the importance of sustaining and increasing vaccination coverage rates to prevent outbreaks of VPDs. Measles is a highly-contagious respiratory disease caused by a virus. It spreads through the air through coughing and sneezing. Measles starts with a fever, runny nose, cough, red eyes, and sore throat, and is followed by a rash that spreads all over the body. About three out of 10 people who get measles will develop one or more complications including pneumonia, ear infections, or diarrhea. Complications are more common in children younger than age 5 and adults. Measles cases and outbreaks still occur in countries in Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific. Worldwide, about 20 million people get measles each year; about 146,000 die. Each year, unvaccinated people get infected while in other countries and bring the disease into the United States and spread it to others. Since 2000, when measles was declared eliminated from the U.S., the annual number of people reported to have measles ranged from a low of 37 people in 2004 to a high of 668 people in 2014.