1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Detailed Table of Contents (PDF Download)

CONTENTS Preface xix Introduction xxi Acknowledgments xxvii PART I CONTENT REGULATION 1 CHAPTER 1 BOOKS AND MAGAZINES 3 A. Violence 3 Rice v. Paladin Enterprises 4 Braun v. Soldier of Fortune Magazine, Inc. 11 Einmann v. Soldier of Fortune Magazine, Inc. 18 B. Censorship 25 Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan 25 CHAPTER 2 MUSIC 29 A. Violence 29 Weirum v. RKO General, Inc. 29 McCollum v. CBS, Inc. 33 Matarazzo v. Aerosmith Productions, Inc. 40 Davidson v. Time Warner 42 Pahler v. Slayer 51 B. Censorship 56 Luke Records v. Navarro 57 Marilyn Manson v. N.J. Sports & Exposition Auth. 60 Southeastern Promotions, Ltd. v. Conrad 71 xi xii Contents CHAPTER 3 TELEVISION 79 A. Violence 79 Olivia N. v. NBC 80 Graves v. WB 84 Zamora v. CBS 89 B. Censorship 94 Writers Guild of Am., West Inc. v. ABC, Inc. 94 F.C.C. v. Fox Television Stations, Inc. 103 CHAPTER 4 FILM 115 A. Violence 115 Byers v. Edmondson 117 Lewis v. Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. 122 B. Censorship 128 Swope v. Lubbers 128 Appendix 1: The Movie Rating System 134 United Artists Corporation v. Maryland State Board of Censors 141 Miramax Films Corp. v. Motion Picture Ass’n of Am., Inc. 145 C. Both Sides of the Censor Debate 151 MPAA Ratings Chief Defends Movie Ratings 151 Censuring the Movie Censors 153 CHAPTER 5 VIDEO GAMES 159 A. Violence 159 Watters v. TSR 160 James v. Meow Media 164 Sanders v. Acclaim Entertainment, Inc. 174 Wilson v. Midway Games 186 B. Censorship 189 Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Assoc. -

La Construcción Histórica En La Cinematografía Norteamericana

Tesis doctoral Luis Laborda Oribes La construcción histórica en la cinematografía norteamericana Dirigida por Dr. Javier Antón Pelayo Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Departamento de Historia Moderna Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona 2007 La historia en la cinematografía norteamericana Luis Laborda Oribes Agradecimientos Transcurridos ya casi seis años desde que inicié esta aventura de conocimiento que ha supuesto el programa de doctorado en Humanidades, debo agradecer a todos aquellos que, en tan tortuoso y apasionante camino, me han acompañado con la mirada serena y una palabra de ánimo siempre que la situación la requiriera. En el ámbito estrictamente universitario, di mis primeros pasos hacia el trabajo de investigación que hoy les presento en la Universidad Pompeu Fabra, donde cursé, entre las calles Balmes y Ramon Trias Fargas, la licenciatura en Humanidades. El hado o mi más discreta voluntad quisieron que iniciara los cursos de doctorado en la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, donde hoy concluyo felizmente un camino repleto de encuentros. Entre la gente que he encontrado están aquellos que apenas cruzaron un amable saludo conmigo y aquellos otros que hicieron un alto en su camino y conversaron, apaciblemente, con el modesto autor de estas líneas. A todos ellos les agradezco cuanto me ofrecieron y confío en haber podido ofrecerles yo, a mi vez, algo más que hueros e intrascendentes vocablos o, como escribiera el gran bardo inglés, palabras, palabras, palabras,... Entre aquellos que me ayudaron a hacer camino se encuentra en lugar destacado el profesor Javier Antón Pelayo que siempre me atendió y escuchó serenamente mis propuestas, por muy extrañas que resultaran. -

Literary Miscellany

Literary Miscellany Including Recent Acquisitions. Catalogue 286 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.reeseco.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are consid- ered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering and a Fax machine for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inven- tory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment. Institutional billing requirements may, as always, be accommodated upon request. -

History of the Welles Family in England

HISTORY OFHE T WELLES F AMILY IN E NGLAND; WITH T HEIR DERIVATION IN THIS COUNTRY FROM GOVERNOR THOMAS WELLES, OF CONNECTICUT. By A LBERT WELLES, PRESIDENT O P THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OP HERALDRY AND GENBALOGICAL REGISTRY OP NEW YORK. (ASSISTED B Y H. H. CLEMENTS, ESQ.) BJHttl)n a account of tljt Wu\\t% JFamtlg fn fHassssacIjusrtta, By H ENRY WINTHROP SARGENT, OP B OSTON. BOSTON: P RESS OF JOHN WILSON AND SON. 1874. II )2 < 7-'/ < INTRODUCTION. ^/^Sn i Chronology, so in Genealogy there are certain landmarks. Thus,n i France, to trace back to Charlemagne is the desideratum ; in England, to the Norman Con quest; and in the New England States, to the Puri tans, or first settlement of the country. The origin of but few nations or individuals can be precisely traced or ascertained. " The lapse of ages is inces santly thickening the veil which is spread over remote objects and events. The light becomes fainter as we proceed, the objects more obscure and uncertain, until Time at length spreads her sable mantle over them, and we behold them no more." Its i stated, among the librarians and officers of historical institutions in the Eastern States, that not two per cent of the inquirers succeed in establishing the connection between their ancestors here and the family abroad. Most of the emigrants 2 I NTROD UCTION. fled f rom religious persecution, and, instead of pro mulgating their derivation or history, rather sup pressed all knowledge of it, so that their descendants had no direct traditions. On this account it be comes almost necessary to give the descendants separately of each of the original emigrants to this country, with a general account of the family abroad, as far as it can be learned from history, without trusting too much to tradition, which however is often the only source of information on these matters. -

Charles Bartlett Interviewer: Fred Holborn Date of Interview: January 6, 1965 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C

Charles Bartlett Oral History Interview – JFK #1, 1/6/1965 Administrative Information Creator: Charles Bartlett Interviewer: Fred Holborn Date of Interview: January 6, 1965 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C. Length: 91 pp. Biographical Note Bartlett, Washington correspondent for the Chattanooga Times from 1948 to 1962, columnist for the Chicago Daily News, and personal friend of John F. Kennedy (JFK), discusses his role in introducing Jacqueline Bouvier to JFK, JFK’s relationship with Lyndon Baines Johnson, and JFK’s Cabinet appointments, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed October 11, 1983, copyright of these materials has been assigned to United States Government. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. Direct your questions concerning copyright to the reference staff. -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR CECIL B. LYON Interviewed

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR CECIL B. LYON Interviewed by: John Bovey Initial interview date: October 26, 1988 Copyright 1998 A ST TABLE OF CONTENTS Early career System of promotion in Foreign Service areer officers v. political appointees uba 1931 Economic and political discontent Issuing visas Hong Kong 1932-1933 Trachoma hinese section of Hong Kong Scattering ashes in the Seven Seas To)yo 1933 Japanese reverence for emperor Relations ,ith Japanese Embassy postings policies Sambo and the emperor Pe)ing 1934-193. Japanese invasion Playing polo hinese response invasion E/periences ,ith hinese coolie hiang Kai-she) American civilians in Pe)ing Order for hile hile 193.-1943 Ambassador Norman Armour Inauguration and E/-president Alessandri 1 1S attitude to,ard hile Disparity in income distribution Ambassador 2o,ers Pearl Harbor attac) 1S pressure on hile to brea) relations ,ith A/is 3ice-President 4allace5s visit Attempted meeting bet,een 4allace and Alessandri hilean political situation airo 193.-1943 King Farou) President Roosevelt5s visit Ibn Saud 2ritish presence in Egypt River Plate Affairs 1946-194. Rio Treaty 1947 Revolution during the 2ogota onference8 2ogotaso 4arsa, 194.-1950 2erlin airlift Post-,ar 4arsa, Relations ,ith Poles Disappearance of the Field family Polish airports Polish reaction to Korean 4ar atholicism in Poland 2erlin 1951-1954 Spandau prison ontrast bet,een East and 4est 2erlin Soviet-1S relations in 2erlin Ta)ing Adlai Stevenson to East 2erlin State Department 1954-1955 Mc arthyism Relations ,ith Secretary Dulles and Adenauer Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs hile 1956-195. -

Ocm08458220-1808.Pdf (13.45Mb)

1,1>N\1( AACHtVES ** Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from University of Massachusetts, Boston http://www.archive.org/details/pocketalmanackfo1808amer ; HUSETTS ttttter UnitedStates Calendar; For the Year of our LORD 13 8, the Thirty-fecond of American Independence* CONTAINING . Civil, Ecclrfaflirol, Juiicial, and Military Lids in MASSACHUSE i'TS ; Associations, and Corporate Institutions, tor literary, agricultural, .nd amritablt Purpofes. 4 Lift of Post-Towns in Majfacjufetts, with the the o s s , Names of P r-M a ters, Catalogues of the Officers of the GENERAL GOVERNMENT, its With feveral Departments and Eftabiifhments ; Tunes of jhc Sittings ol the feveral Courts ; Governors in each State ; Public Duties, &c. USEFUL TABLES And a Variety of other intereftiljg Articles. * boston : Publiflied by JOHN WEtT, and MANNING & LORING. Sold, wholesale and retail, at their Book -Stores, CornhUl- P*S# ^ytu^r.-^ryiyn^gw tfj§ : — ECLIPSES for 1808. will eclipfes .his THERE befiv* year ; three of the Sun, and two of the Moon, as follows : • I. The firit will be a total eclipfe of the Moon, on Tuefday morning, May io, which, if clear weather, will be viiible as follows : H. M. Commencement of the eclipfe 1 8^ The beginning or total darknefs 2 6 | Mean The middle of the eciiple - 2 53 )> iimc Ending of total darkneis - 3 40 | morning. "Ending of the eclipfe 4 ^8 J The duration of this is eclipfe 3 hours and 30 minutes ; the duration of total darkneis, 1 hour 34 minutes ; and the cbfcunty i8| digits, in the fouthern half of the earth's (hatiow. -

162 Congressional Record-House

162 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE JANUARY 7 He also, from the Committee on Post Offices and Post RULES OF CIVIL PROCEDURE, UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURTS Roads, reported favorably the nominations of several post Mr. LAMBETH. Mr. Speaker, from the Committee on masters. Printing I report back favorably <H. Rept. No. 1663) a reso The PRESIDING OFFICER. The reports will be placed lution and ask for its immediate consideration. on the Executive Calendar. The Clerk read as follows: EXECUTIVE MESSAGES REFERRED House Resolution 395 The PRESIDING OFFICER (Mr. NEELY in the chair), as Resolved, That 9,000 additional copies of House Document 460, current session, entitled "A letter from the Attorney General of in executive session, laid before the Senate messages from the United States transmitting the Rules of Civil Procedure for the the President of the United States submitting several nomi District Courts of the United States," be printed for the use of the nations, a treaty, and a convention, which were referred to House document room. the appropriate committees. Mr. COCHRAN. Mr. Speaker, will the gentleman yield (For nominations this day received, see the end of Senate for a question? proceedings.) Mr. LAMBETH. I yield. RECESS Mr. COCHRAN. Does not the gentleman feel that it Mr. BARKLEY. I move that the Senate take a recess until would be fairer to the Members of the House if the dis 11 o'clock tomorrow morning. tribution were through the folding room· instead of the The motion was agreed to; and (at 5 o'clock and 10 min House document room? This is a very, very · important utes p.m.) the Senate took a recess until tomorrow, Satur- document. -

Allied Relations and Negotiations with Spain A

Allied Relations and Negotiations With Spain A. From Spanish "Non-Belligerency" to Spanish Neutrality1 Shortly after the outbreak of the War in September 1939, Spanish dictator General Francisco Franco released an official decree of neutrality in the conflict, despite his open ideological affinity with the Axis leaders who had provided him with critical support in the Spanish Civil War. Nevertheless, he hovered on the brink of intervention on the side of the Axis through much of 1940 and 1941, and even contributed a force of Spanish volunteers estimated to be as many as 40,000, known as the Blue Division, which served as the German 250th Division on the Russian Front from mid-1941 until October 1943. The possibility of Spanish belligerency was premised on an early German victory over Britain and on German agreement to Spanish territorial expansion in Africa into French Morocco and perhaps even in Europe at the expense its neighbors, Vichy France and neutral Portugal. The United States and Britain joined in a continuing effort to keep Franco's Spain out of the War by providing essential exports like gasoline and grain to prop up the Spanish economy, which had been in a state of collapse since the end of the Spanish Civil War. The close ideological and political ties between the Franco dictatorship and those of Germany and Italy were never misapprehended by the United States and Britain. After 1941 Spain drifted gradually from imminent belligerency toward a demonstratively pro-Axis neutrality. Spain cooperated with the Allies in humanitarian efforts, allowing safe passage through Spain of downed Allied fliers, escaped Allied prisoners, and civilian refugees, including Jews.2 The nature of Spain's neutrality in World War II turned in significant measure on Allied and Spanish perceptions of the danger of German invasion. -

A70 Pkit 4.Pdf

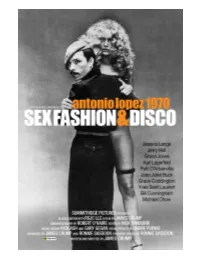

PRESS KIT Antonio Lopez 1970: Sex Fashion & Disco A Film by James Crump Featuring: Jessica Lange, Grace Jones, Bob Colacello, Jerry Hall,Grace Coddington, Patti D’Arbanville, Karl Lagerfeld, Juan Ramos, Bill Cunningham, Jane Forth, Yves Saint Laurent, Donna Jordan, Paul Caranicas, Joan Juliet Buck, Corey Tippin and Michael Chow. Film soundtrack features music by: Donna Summer,Marvin Gaye, Evelyn “Champagne” King, Isaac Hayes,Curtis Mayfield, Chic and the Temptations. Summitridge Pictures and RSJC LLC present a film by James Crump. Edited by Nick Tamburri. Visual Effects by Andre Purwo. Cinematography by Robert O’Haire. Produced by James Crump and Ronnie Sassoon. Sex Fashion & Disco is a feature documentary-based time capsule concerning Paris and New York between 1969 and 1973 and viewed through the eyes of Antonio Lopez (1943-1987), the dominant fashion illustrator of the time, and told through the lives of his colorful and some-times outrageous milieu. A native of Puerto Rico and raised in The Bronx, Antonio was a seductive arbiter of style and glamour who, beginning in the 1960s, brought elements of the urban street and ethnicity to bear on a postwar fashion world desperate for change and diversity. Counted among Antonio’s discoveries— muses of the period—were unusual beauties such as Cathee Dahmen, Grace Jones, Pat Cleveland, Tina Chow, Jessica Lange, Jerry Hall and Warhol Superstars Donna Jordan, Jane Forth and Patti D’Arbanville among others. Antonio’s inner circle in New York during this period was also comprised of his personal and creative partner, Juan Ramos (1942-1995), also Puerto Rican-born and raised in Harlem, makeup artist Corey Tippin and photographer Bill Cunningham, among others. -

House Okays $5 Billion for Energy Research

> PAGE TWENTY-TWO - MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD, Manchester. Conn., Fri„ June 20, 1975 Testimonial OBITUARIES Enters Race FIRE C A L L S Canceled At his request, the For District Board testimonial planned for Thomas MANCHESTER (Manchester Ambulance) C. Monahan has been called off. lianrljfHtPr Surntng M? ralb Thursday, 11:47 a.m. — gas A third North End man has Flynn, 34, is supervisor of Thursday, 4:04 p.m. — auto Monahan is retiring from the Mrs. Marcella H. Hayes washdown at 17 Armory St. announced he is a candidate for control support functions at accident on 1-84 in the west post he has held for over 16 Raymond Brunell, 47; Mrs. Marcella Hickey Hayes, (Town) MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, JUNE 21, 1975 - VOL. XCIV, No. 223 the Eighth District Board of Combustion Engineering. He is years as Manchester chief Manchester—A City of Village Charm t w e n t y -t w o p a g e s 65, of 206 Oakland St. died bound lane. See story in today’s PRICE: FIFTEEN CENTS Directors. He is John C. Flynn a graduate of Manchester High Today, 1:01 a.m. — auto acci building inspector. He was Thursday at Manchester Herald. (Manchester Am Mental Health Officer Jr. of 31 Strong St. School and has a bachelor’s dent on Hartford Rd. caused the assistant building inspector for Memorial Hospital. She was the bulance) Flynn joins William L. degree from the University of downing of some wires. (Town) over three years before t^ t. widow of John Hayes. Today, 1:59 a.m. -

John Davis Lodge Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft9c6007r1 Online items available Register of the John Davis Lodge papers Finding aid prepared by Grace Hawes and Katherine Reynolds Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 1998 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the John Davis Lodge 86005 1 papers Title: John Davis Lodge papers Date (inclusive): 1886-1987 Collection Number: 86005 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 288 manuscript boxes, 27 oversize boxes, 3 cubic foot boxes, 1 card file box, 3 album boxes, 121 envelopes, 2 sound cassettes, 1 sound tape reel, 1 sound disc(156.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, speeches and writings, dispatches, reports, memoranda, clippings, other printed matter, photographs, sound recordings, and motion picture film relating to the Republican Party, national and Connecticut politics, and American foreign relations, especially with Spain, Argentina and Switzerland. Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org. Creator: Lodge, John Davis, 1903-1985 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access Boxes 310-311 closed. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1986. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], John Davis Lodge papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Alternate Forms Available Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org.