Charles Bartlett Interviewer: Fred Holborn Date of Interview: January 6, 1965 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henry Cabot Lodge

1650 Copyright by CLP Research Partial Genealogy of the Lodges Main Political Affiliation: (of Massachusetts & Connecticut) 1763-83 1789-1823 Federalist ?? 1824-33 National Republican ?? 1700 1834-53 Whig ?? 1854- Republican 1750 Giles Lodge (1770-1852); (planter/merchant) (Emigrated from London, England to Santo Domingo, then Massachusetts, 1791) See Langdon of NH = Abigail Harris Langdon Genealogy (1776-1846) (possibly descended from John, son of John Langdon, 1608-97) 1800 10 Others John Ellerton Lodge (1807-62) (moved to New Orleans, 1824); (returned to Boston with fleet of merchant ships, 1835) (engaged in trade with China); (died in Washington state) See Cabot of MA = Anna Sophia Cabot Genealogy (1821-1901) Part I Henry Cabot Lodge (1850-1924) 1850 (MA house, 1880); (ally of Teddy Roosevelt) See Davis of MA (US House, 1887-93); (US Senate, 1893-1924; opponent of League of Nations) Genealogy Part I = Ann Cabot Mills Davis (1851-1914) See Davis of MA Constance Davis George Cabot Lodge Genealogy John Ellerton Lodge Cabot Lodge (1873-1909) Part I (1878-1942) (1872-after 1823) = Matilda Elizabeth Frelinghuysen Davis (1875-at least 1903) (Oriental art scholar) = Col. Augustus Peabody Gardner = Mary Connally (1885?-at least 1903) (1865-1918) Col. Henry Cabot Lodge Cmd. John Davis Lodge Helena Lodge 1900(MA senate, 1900-01) (from Canada) (US House, 1902-17) (1902-85); (Rep); (newspaper reporter) (1903-85); (Rep) (1905-at least 1970) (no children) (WWI/US Army) (MA house, 1933-36); (US Senate, 1937-44, 1947-53; (movie actor, 1930s-40s); -

Hclassification

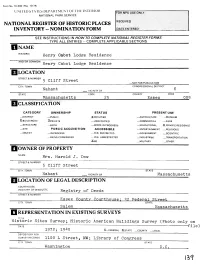

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATHS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Henry Cabot Lodge Residence AND/OR COMMON Henry Cabot Lodge Residence 5 Cliff Street .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Nahant VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Essex 009 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION -XNO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mrs. Harold J. Dow STREET & NUMBER 5 Cliff Street CITY, TOWN STATE Nahant VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Essex County Courthouse: ^2 Federal Street CITY, TOWN STATE Salem Massachusetts I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey; Historic American Buildings Survey (Photo only on DATE ————————————————————————————————————file) 1972; 19^0 X_FEDERAL 2LSTATE _COUNTY _J_OCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS 1100 L Street, NW; Library of Congress Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 3C ORIGINAL SITE X_QOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE This two-story, hip-roofed, white stucco-^covered, lavender- trimmed, brick villa is the only known extant residence associated with Henry Cabot Lodge. -

Pka S&D 1948 Sep

IIKA INITIATES! NOW YOU CAN WEAR A III{ A BA.DGE ORDER IT TODAY FROM THIS OFFICIAL PRICE LIST- PLAIN -UNJEWELED Sister Pin or No. 0 No. 2 No. 3 Plain Be vel Border................... ....................................................... $ 5.25 $ 6.50 $ 9.00 Nugget or Engrdved Border ................................................. ....... 5.7 5 7.00 10.50 Nugget or Engraved Border with 4 Pearl Points........ 7.50 B.75 12 .00 S. M. C . Key ............................................................................ SB .50 S CARP FULL CROWN SET JEWELS No. 0 No. 2 No. 21/, No. 3 Pearl Border ................. ............................ ................. $ 11.50 s 16.00 $ 19.50 $ 22 .50 Pearl Border, C ape Ruby Po ints....... ..................... 11.50 16.00 19.50 22.50 P.earl Bo rder, Ruby or Sapphire Po ints ................ 13.25 17 .50 22 .50 27.50 Pearl Border, Emerald Points ... ·-··························· 16.50 22.00 25.00 30.00 Pearl Border, Di amond Points ................................ 39.50 52.75 62 .50 Bl.50 No.2 c~ . SeT Pea rl and Sapphire Alternating ............................ 16.50 21.00 25.00 30.50 PLAIN PEARL N o. 2 Pea rl and Ruby Alternating ....... .. .... 16.50 21.00 25.00 30.50 Pearl a nd Emera ld Alternating ............................. IB.OO 24.00 30.00 35.00 ~ I Ct. SeT Pearl Diamond Alternating 64 .50 BB .50 105 .50 140.50 and i L"RC I!. All Ruby Border........ IB .OO 23.00 30.00 32 .50 ····················· ~--~' •' Ruby Border, Diamond Poi nts ................................ 44 .00 59.00 73.00 91.50 .. " Ruby a nd Dia mond A lternat ing ·························- 70.00 94.75 11 6.00 150.50 Emerald and Di a mond Alternating ..................... -

THE TAKING of AMERICA, 1-2-3 by Richard E

THE TAKING OF AMERICA, 1-2-3 by Richard E. Sprague Richard E. Sprague 1976 Limited First Edition 1976 Revised Second Edition 1979 Updated Third Edition 1985 About the Author 2 Publisher's Word 3 Introduction 4 1. The Overview and the 1976 Election 5 2. The Power Control Group 8 3. You Can Fool the People 10 4. How It All BeganÐThe U-2 and the Bay of Pigs 18 5. The Assassination of John Kennedy 22 6. The Assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King and Lyndon B. Johnson's Withdrawal in 1968 34 7. The Control of the KennedysÐThreats & Chappaquiddick 37 8. 1972ÐMuskie, Wallace and McGovern 41 9. Control of the MediaÐ1967 to 1976 44 10. Techniques and Weapons and 100 Dead Conspirators and Witnesses 72 11. The Pardon and the Tapes 77 12. The Second Line of Defense and Cover-Ups in 1975-1976 84 13. The 1976 Election and Conspiracy Fever 88 14. Congress and the People 90 15. The Select Committee on Assassinations, The Intelligence Community and The News Media 93 16. 1984 Here We ComeÐ 110 17. The Final Cover-Up: How The CIA Controlled The House Select Committee on Assassinations 122 Appendix 133 -2- About the Author Richard E. Sprague is a pioneer in the ®eld of electronic computers and a leading American authority on Electronic Funds Transfer Systems (EFTS). Receiving his BSEE degreee from Purdue University in 1942, his computing career began when he was employed as an engineer for the computer group at Northrup Aircraft. He co-founded the Computer Research Corporation of Hawthorne, California in 1950, and by 1953, serving as Vice President of Sales, the company had sold more computers than any competitor. -

Mr. Tuck's File of Letters from Jennifer M

Mr. Tuck’s File of Letters from Jennifer M. Allocca’s research; additional notes by Dan Rothman The “Bulletin of the Essex Institute” (Volume XX. 1888. Salem, Mass. Printed 1889.) describes a September 1887 presentation to the Institute by Mr. J. D. Tuck, which provides additional information about the New Boston counterfeiters. https://books.google.com/books?id=BKQUAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA28&lpg=PA28 Joseph Dane Tuck (1817-1900) was a tailor who was born in Beverly, MA and died in that town. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Essex_Institute tells us that the Essex Institute (1848–1992) in Salem, Massachusetts, was “a literary, historical and scientific society.” It maintained a museum, library, historic houses; arranged educational programs; and issued numerous scholarly publications. In 1992 the institute merged with the Peabody Museum of Salem to form the Peabody Essex Museum. The correspondence in Mr. Tuck’s file gives us an interesting picture of how Boston-area bankers struggled with the expensive problem of counterfeit bills. Representatives of the banks whose notes had been counterfeited met to discuss what should be done. They feared that Mr. Peasley (or Peaslee) who had engraved the plates would flee when he learned of the arrest of the New Boston counterfeiters. The bankers knew that Stephen Burroughs, the most famous counterfeiter of his day, was busy producing paper currency in Stanstead, Quebec (in the Eastern Townships of Lower Canada), just a few miles north of the Vermont border. How could they apprehend him and place him “in the way to the Gallows”? They worried that at least one of the bailiffs they might send to Stanstead to collect evidence and arrest the counterfeiters was himself a member of the gang. -

John Davis Lodge Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft9c6007r1 Online items available Register of the John Davis Lodge papers Finding aid prepared by Grace Hawes and Katherine Reynolds Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 1998 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the John Davis Lodge 86005 1 papers Title: John Davis Lodge papers Date (inclusive): 1886-1987 Collection Number: 86005 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 288 manuscript boxes, 27 oversize boxes, 3 cubic foot boxes, 1 card file box, 3 album boxes, 121 envelopes, 2 sound cassettes, 1 sound tape reel, 1 sound disc(156.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, speeches and writings, dispatches, reports, memoranda, clippings, other printed matter, photographs, sound recordings, and motion picture film relating to the Republican Party, national and Connecticut politics, and American foreign relations, especially with Spain, Argentina and Switzerland. Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org. Creator: Lodge, John Davis, 1903-1985 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access Boxes 310-311 closed. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1986. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], John Davis Lodge papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Alternate Forms Available Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1962-09-20

• enate Promises Force to Stop Red Advances In Cuba WASHINGTON (A'I - 'rwo Senate committees hung out a blunt ad I vance warning 1.0 the Communist world Wednesday ; The United States • will use force i( necessary to halt the advance of Communism in this ~ hemisphere. .. The Senate Foreign Relations and Armed Services committees The ·Weather unanimously approved II joint resolution stilling U.S. determination ; "To prevent by whatever means may be necessary, including the F.lr and c.... IIII'*' cM! I.V, nse of arms, the Ma rxist-Leninist regime in Cuba from extending by wilh hlths In tM 6ft. Plrtly lorce or threat of force its aggressive or subversive activities to any an douety .nd warlMr ItIIltht, plIrt of this hemisphere." I 011 ~ey House FOI'eign Affairs Com- [OI·t of a European power to ex Serving the State University of Io wa and the People of Iowa City tnlttec !l'cmbers were in consult~· lend its syslem into the Weslern Uon with the Sena~e groups III Hemisphere ; the Rio treaty of Established in 1868 Associated Pre:s Leased Wire and Wirephoto 10wa City, 10WII, Thursday, September 20, 1 2 hammering out the final language. 1947 which holds that an attack j Their commiltee was working on a on ~ne American stale would be similar resolulion_ ~II attack on all ; and the declara- The firm statement Or policy, ti(ln of loreign ministers at Punta expected to be approved Thursday del Este, Uruguay, last January. • by both houses of Congress and That declaration stated: "The sent lo Presidcnt Kennedy for his present government of Cuba has signature, also states U.S. -

Noticias De Actualidad. Núm. 8, 15 De Abril De 1957

TAOS, RELIQUIA ESPAÑOLA EN NORTEAMÉRICA o si, por el contrario, pueden concurrir a él escritores de otros países.—-Pedro José Ro dríguez, Salamanca. 12.—El Premio Pulitzer de novela se otor ga a una creación imaginaria, publicada en forma de libro durante el año de que se tra te, por un autor norteamericano. Preferi blemente debe referirse a un aspecto de la vida en los Estados Unidos. para que el deudor envíe un cheque o el im das células nerviosas de la médula, que no se porte en metálico de su pago. regeneran. Lo único que de momento se pue PETRÓLEO de lograr es, como usted dice, prevenirse con Las perforaciones petrolíferas que se reali EL ORIGEN DEL $ tra tan terrible enfermedad. zan en España con técnicos americanos, ¿ co NOTICIAS DE ACTUALIDAD quiere saber la ¿ Es verdad que el símbolo del dólar tiene rresponden al programa de Cooperación Eco opinión de sus lectores sobre cuestiones de su origen en el escudo de Carlos I de España? MARINE CORPS nómica?—Wladimir Nadal, Lérida. muflió interés para España y los Estados Uni —José Millas, Bétera (Valencia). Quisiera saber: (1) Si la Infantería de Ma R.—No. Dichas perforaciones están patroci dos. Escríbanos expresando su punto de vis B.—Se ha buscado un precedente español rina norteamericana está totalmente indepen nadas por el I. N. I. ta. El autor de cada carta seleccionada para de la marca del dólar, el familiar símbolo #. dizada de la Marina; (2) si los mandos de la su publicación recibirá un libro como premio. Este puede ser la columna de Hércules de al Marina pueden alcanzar mayor graduación AL CÉSAR.. -

On 8Th Ballot; Ontest

.-film-*.. -Tfjili— /-o-r'y 1 •:V ' f. 'i! ;,*■ - T . ■ ' • ■ . - , , , ’ 75' r -V , ^ ■ . I ■ ■ ■ ■ •: ■ •• ' •' ■■■■■■■■•.•'.A'...'.. * ‘ •/. V * v ’' ‘ 7 ''; •. ■■ ,V' ^ ‘ ■ V. • '1 - ‘ i." V ■ 1' , “ , ■. f- -f ’• ,v .V * ^A. -i . I *', w *'< . \ 5--4'; f'- -'fff. V-'t« »■' TUESDAY, JUNE i, IteS : Average Dally Not Prcaa Rub *'■. <■ •••' • .• Snntta^ . Far 'pw Badad The WMthor . : Juae's. iS«S , ' Forecast of U.,a. WaatkiW B rip k ^ ' 'i«<i>*ifi'ii«iiii»i' ss#* . .K il Wild had been,oharged wtth oMsto- i n>e June conference of dear and seal te^gh^ Lsiw |a . '1- the Service Bureau for Women’s l2thC iraiit tog iiioBagr or, g o ^ uhdtr. gala* LARRABEE'S 13,595 js.y.4, w S lib W T d w ii OrganlsaUons.wW lintude oonvet- pratiiiaao. The oooO tovolvad a had r ef the AnOt 800. T h a n d ay. onany' 'wM siaosiU b a r b e r s h o p ■ tft' aatton houM - w ith International eh«BI| Paid to gwid daith fOr auto XtotU June 2L ROhwrt M le h a ^ ef OhmalaUeB aHe mUd. High 7I| to 80. ^ Court Cases work oone’cn ms oar. Raatltutkto ,10, M ' 800 caiarter Oak St, for ^mtumm- o* aw jKwnimr vlsiton, exhOdta, open fbrums ispraoNsnuan Manc^$ter-^A CUy of ViUage Charm H i l l . ..... .... .......... .......... ... ............ - f i i » 9 m t n f ■owUarlM«a«, wlU w et and organisation teetmlqtM classes has been or la hatog made. It wSs court .trial to (toarge of larceny — reported, value Oil, ' ' " ’ . Open Tlmroday, WrMay. -

01Connectorjul

The CONNector - JULY 2001 JULY 2001 Volume 3 Number 3 IN THIS ISSUE The State Librarian's Column The State Librarian s reflects upon the vast network of close collaboration between the State Library and all segments of the library community. State Library Board Notes Significant activities of the State Library Board as per the May 21, 2001 meeting. Governor's Service Awards - July 2000 - July, 2001 Congratulations to four of our CSL employees for excellent service. CSL Affirmative Action Plan 2001 The State Commission on Human Rights and Opportunities (CHRO) gave approval of the 2001 Affirmative Action Plan. A message from Kendall Wiggin to CHRO Director Cynthia Watts Elder confirms our commitment to affirmative action. Employee Recognition Awards for Years of State Service Employees were recognized for their years of state service in Memorial Hall, Museum of Connecticut History on June 11, 2001. Partnerships Eagle Scout Candidate Creates "Sensory Garden" This "Sensory Garden" garden spans the entire front of the library comes alive for people with different disabilities. LBPH is grateful to James Dossot for leading the team to create this wonderful environment for its patrons. History Day Students and the Connecticut State Library Students participating in the 2001 National History Day competition were shown the collections and resources the Connecticut State Library has to offer. Connecticut State Library New Hours The new hours of the Connecticut State Library starting July 28, 2001. Honoring the Past Biographies of Judges & Attorneys Selected biographies, obituaries and remarks of notable judges and attorneys can be found in the original early volumes of the Connecticut Report, including comprehensive information about Noah Webster. -

![Papers of Clare Boothe Luce [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4480/papers-of-clare-boothe-luce-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-1694480.webp)

Papers of Clare Boothe Luce [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF

Clare Boothe Luce A Register of Her Papers in the Library of Congress Prepared by Nan Thompson Ernst with the assistance of Joseph K. Brooks, Paul Colton, Patricia Craig, Michael W. Giese, Patrick Holyfield, Lisa Madison, Margaret Martin, Brian McGuire, Scott McLemee, Susie H. Moody, John Monagle, Andrew M. Passett, Thelma Queen, Sara Schoo and Robert A. Vietrogoski Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2003 Contact information: http://lcweb.loc.gov/rr/mss/address.html Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2003 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms003044 Latest revision: 2008 July Collection Summary Title: Papers of Clare Boothe Luce Span Dates: 1862-1988 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1930-1987) ID No.: MSS30759 Creator: Luce, Clare Boothe, 1903-1987 Extent: 460,000 items; 796 containers plus 11 oversize, 1 classified, 1 top secret; 319 linear feet; 41 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Journalist, playwright, magazine editor, U.S. representative from Connecticut, and U.S. ambassador to Italy. Family papers, correspondence, literary files, congressional and ambassadorial files, speech files, scrapbooks, and other papers documenting Luce's personal and public life as a journalist, playwright, politician, member of Congress, ambassador, and government official. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. Personal Names Barrie, Michael--Correspondence. Baruch, Bernard M. -

Henry Cabot Lodge Collection: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8hm5fk8 No online items Henry Cabot Lodge Collection: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Gayle M. Richardson, July 8, 2010. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2010 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Henry Cabot Lodge Collection: mssHM 73270-73569 1 Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Henry Cabot Lodge Collection Dates (inclusive): 1871-1925 Collection Number: mssHM 73270-73569 Creator: Lodge, Henry Cabot, 1850-1924. Extent: 300 pieces in 6 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection consists of correspondence and a small amount of printed ephemera of American statesman Henry Cabot Lodge (1850-1924). The majority of the letters are by Lodge; these include a very small number of personal letters but are mainly letters by Lodge to other political leaders of the time or to his Massachusetts constituents. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher.