The Cabots of Boston - Early Aviation Enthusiasts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

51 Hot-Air Balloons

We’re on the www. Thanks to Don Taylor the MAAA has now its own individual Internet web site. Look us up on www.aussiemossie.asn.au. Don has slaved over a hot PC for many nights teaching himself how to undertake the task, and the result as you will see is a credit to him. He welcomes all feedback, as well as genuine articles that are unique, as he does not want the site to be just another list of numbers but wants to have articles that portray the human side as well. You can email him with your anecdotes via the Contact Us section on the site. Our thanks also go to stalwart Brian Fillery for making his personal site available to the MAAA for the past few years. It was greatly ap- preciated. By the way if you are look- ing for the home page, there is not one, it is now known as the Hangar page (Don’s humour—you can tell by the smirk on his face). THE AUSSIE MOSSIE / APRIL 2008 / 1 The President’s Log—by Alan Middleton OAM in the RAAF post 1945, retiring ers moved into Coomalie Creek in with the rank of Air Vice Mar- November 1942 and it remained an shal. operational base until the end of the The Gillespie Room is named war. for Sqn Ldr Jim Gillespie, a Pilot with 87 who died as a A report was recently seen in an result of a crash on takeoff at Airforce Association publication on Coomalie Creek on 2 August the death of Fred Stevens DFC, the 1945. -

Charles Bartlett Interviewer: Fred Holborn Date of Interview: January 6, 1965 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C

Charles Bartlett Oral History Interview – JFK #1, 1/6/1965 Administrative Information Creator: Charles Bartlett Interviewer: Fred Holborn Date of Interview: January 6, 1965 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C. Length: 91 pp. Biographical Note Bartlett, Washington correspondent for the Chattanooga Times from 1948 to 1962, columnist for the Chicago Daily News, and personal friend of John F. Kennedy (JFK), discusses his role in introducing Jacqueline Bouvier to JFK, JFK’s relationship with Lyndon Baines Johnson, and JFK’s Cabinet appointments, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed October 11, 1983, copyright of these materials has been assigned to United States Government. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. Direct your questions concerning copyright to the reference staff. -

1/98 Germany (Country Code +49) Communication of 5.V.2020: The

Germany (country code +49) Communication of 5.V.2020: The Bundesnetzagentur (BNetzA), the Federal Network Agency for Electricity, Gas, Telecommunications, Post and Railway, Mainz, announces the National Numbering Plan for Germany: Presentation of E.164 National Numbering Plan for country code +49 (Germany): a) General Survey: Minimum number length (excluding country code): 3 digits Maximum number length (excluding country code): 13 digits (Exceptions: IVPN (NDC 181): 14 digits Paging Services (NDC 168, 169): 14 digits) b) Detailed National Numbering Plan: (1) (2) (3) (4) NDC – National N(S)N Number Length Destination Code or leading digits of Maximum Minimum Usage of E.164 number Additional Information N(S)N – National Length Length Significant Number 115 3 3 Public Service Number for German administration 1160 6 6 Harmonised European Services of Social Value 1161 6 6 Harmonised European Services of Social Value 137 10 10 Mass-traffic services 15020 11 11 Mobile services (M2M only) Interactive digital media GmbH 15050 11 11 Mobile services NAKA AG 15080 11 11 Mobile services Easy World Call GmbH 1511 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1512 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1514 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1515 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1516 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1517 11 11 Mobile services Telekom Deutschland GmbH 1520 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone GmbH 1521 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone GmbH / MVNO Lycamobile Germany 1522 11 11 Mobile services Vodafone -

Bundesländer-Kartei

Baden - Württemberg Ideenbox - © Grundschul © Grundschul Bayern Ideenbox - © Grundschul © Grundschul Baden - Württemberg Fläche: 35.751,46 km² Einwohnerzahl: ca. 11.069.530 → 310 Einwohner pro km² Landeshauptstadt: Stuttgart Bekannte Städte: Heidelberg, Heilbronn, Freiburg, Karlsruhe, Mannheim, Pforzheim, Reutlingen, Ulm Längste Flüsse: Rhein, Donau, Neckar, Kocher, Jagst Höchste Berge: Feldberg (1493 m), Seebuck (1449 m), Herzogenhorn (1415 m) Bekannte Landschaften: Schwarzwald, Schwäbische Alb, Odenwald, Bodensee Sehenswürdigkeiten: Schloss Heidelberg, Burg Hohenzollern, Ulmer Münster, Wilhelma, Mercedes-Benz-Museum, Titisee, Pfahlbauten Uhldingen Angeberwissen: Baden-Württemberg wurde am 25. April 1952 aus den Ländern Württemberg- Hohenzollern, Baden und Württemberg-Baden gegründet. Bayern Fläche: 70.541,57 km² Einwohnerzahl: ca. 13.124.730 → 186 Einwohner pro km² Landeshauptstadt: München Bekannte Städte: Nürnberg, Augsburg, Regensburg, Ingolstadt, Fürth, Würzburg, Erlangen Längste Flüsse: Donau, Main, Inn, Iller, Lech, Isar Höchste Berge: Zugspitze (2962 m), Schneefernkopf (2875 m), Wetterspitzen (2747 m) Bekannte Landschaften: Altmühltal, Bayrischer Wald, Fränkische Schweiz, Bodensee Sehenswürdigkeiten: Schloss Neuschwanstein, Nürnberger Kaiserburg, Bamberger Dom Angeberwissen: Bayern ist das größte Bundesland Deutschlands. Bayern ist seit 1918 ein Freistaat, wurde also von da an nicht mehr von einem König regiert. Die Bezeichnung blieb erhalten, obwohl heute alle Bundesländer gleichberechtigt sind. Berlin Ideenbox - © Grundschul -

Henry Cabot Lodge

1650 Copyright by CLP Research Partial Genealogy of the Lodges Main Political Affiliation: (of Massachusetts & Connecticut) 1763-83 1789-1823 Federalist ?? 1824-33 National Republican ?? 1700 1834-53 Whig ?? 1854- Republican 1750 Giles Lodge (1770-1852); (planter/merchant) (Emigrated from London, England to Santo Domingo, then Massachusetts, 1791) See Langdon of NH = Abigail Harris Langdon Genealogy (1776-1846) (possibly descended from John, son of John Langdon, 1608-97) 1800 10 Others John Ellerton Lodge (1807-62) (moved to New Orleans, 1824); (returned to Boston with fleet of merchant ships, 1835) (engaged in trade with China); (died in Washington state) See Cabot of MA = Anna Sophia Cabot Genealogy (1821-1901) Part I Henry Cabot Lodge (1850-1924) 1850 (MA house, 1880); (ally of Teddy Roosevelt) See Davis of MA (US House, 1887-93); (US Senate, 1893-1924; opponent of League of Nations) Genealogy Part I = Ann Cabot Mills Davis (1851-1914) See Davis of MA Constance Davis George Cabot Lodge Genealogy John Ellerton Lodge Cabot Lodge (1873-1909) Part I (1878-1942) (1872-after 1823) = Matilda Elizabeth Frelinghuysen Davis (1875-at least 1903) (Oriental art scholar) = Col. Augustus Peabody Gardner = Mary Connally (1885?-at least 1903) (1865-1918) Col. Henry Cabot Lodge Cmd. John Davis Lodge Helena Lodge 1900(MA senate, 1900-01) (from Canada) (US House, 1902-17) (1902-85); (Rep); (newspaper reporter) (1903-85); (Rep) (1905-at least 1970) (no children) (WWI/US Army) (MA house, 1933-36); (US Senate, 1937-44, 1947-53; (movie actor, 1930s-40s); -

Regionen Der Mitte

Gerhard Cassing Regionen der Mitte Internet-Recherche zur raumstrukturellen Verflechtung von Nordhessen, Südniedersachsen und Nordthüringen Oberzentrum Verdichtungsraum Teiloberzentrum Ordnungsraum Mittelzentrum Ländlicher Raum - Verflechtungsber. KS/GÖ Autobahn, B 27 Ländlicher Raum Übergangsbereich Eisenbahn (ARL) Gerhard Cassing Regionen der Mitte Internet-Recherche zur raumstrukturellen Verflechtung von Nordhessen, Südniedersachsen und Nordthüringen Herausgeber: Regionalverband Südniedersachsen e.V. Barfüßerstraße 1, 37073 Göttingen [email protected] 0551-5472810 www.regionalverband.de in Zusammenarbeit mit: Regierungspräsidium Kassel - Dezernat Regionalplanung Steinweg 6, 34117 Kassel www.rp-kassel.de Regionale Planungsstelle Nordthüringen Schachtstraße 45, 99706 Sondershausen, www.regionalplanung.thueringen.de Göttingen, Juni 2004 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorbemerkung....................................................................................................................4 1. Verflechtungsanalyse: Mittlerfunktion der Mitte-Regionen...........................5 1.1 Deutschland-Mitte als Verflechtungsraum: Transit- oder Transferraum?...............5 1.2 Mitte Deutschlands im Wandel: Die neue Mitte....................................................13 1.3 Mitte-D als Marketingraum: Internet-Präsentationen............................................17 2. Siedlungsstruktur mittlerer Dichte: Attraktives Städtenetz Mitte.................41 2.1 Bevölkerung und Wohnen: Verstädterung der Lebensräume..............................41 -

Handbook for Students 2005–2006

Faculty of Arts and Sciences Handbook for Students 2005–2006 Harvard College Official Register of Harvard University PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS Faculty of Arts and Sciences Harvard College Handbook for Students 2005–2006 Vol. 20, No. 10 August 1, 2005 Review of academic, financial, and other considerations leads to changes in the poli- cies, rules, and regulations applicable to students. The Faculty of Arts and Sciences there- fore reserves the right to make changes at any time. These changes may affect such matters as tuition and all other fees, courses, degrees and programs offered (including the modifica- tion or possible elimination of degrees and programs), degree and other academic require- ments, academic policies, rules pertaining to student conduct and discipline, fields or areas of concentration, and other rules and regulations applicable to students. While every effort has been made to ensure that this book is accurate and up-to-date, it may include typographical or other errors. Changes are periodically made to this publica- tion and will be incorporated in new editions. Barry S. Kane, Registrar Stephanie H. Kenen, Assistant Dean of Harvard College John T. O’Keefe, Assistant Dean of Harvard College Patricia A. O’Brien, Associate Registrar, Courses, Scheduling, and Publications Hana Boston-Howes, Coordinator The Official Register of Harvard University (ISSN #0199-1787) is published thirteen times a year, four times in July, four times in August, one time in September, November, January, February, and March. The Official Register of Harvard University is published by Harvard Printing and Publication Services, 219 Western Avenue, Allston, Massachusetts 02134. -

Front Cover: Airbus 2050 Future Concept Aircraft

AEROSPACE 2017 February 44 Number 2 Volume Society Royal Aeronautical www.aerosociety.com ACCELERATING INNOVATION WHY TODAY IS THE BEST TIME EVER TO BE AN AEROSPACE ENGINEER February 2017 PROPELLANTLESS SPACE DRIVES – FLIGHTS OF FANCY? BOOM PLOTS RETURN TO SUPERSONIC FLIGHT INDIA’S NAVAL AIR POWER Have you renewed your Membership Subscription for 2017? Your membership subscription was due on 1 January 2017. As per the Society’s Regulations all How to renew: membership benefits will be suspended where Online: a payment for an individual subscription has Log in to your account on the Society’s www.aerosociety.com not been received after three months of the due website to pay at . If you date. However, this excludes members paying do not have an account, you can register online their annual subscriptions by Direct Debits in and pay your subscription straight away. monthly installments. Additionally members Telephone: Call the Subscriptions Department who are entitled to vote in the Society’s AGM on +44 (0)20 7670 4315 / 4304 will lose their right to vote if their subscription has not been paid. Cheque: Cheques should be made payable to the Royal Aeronautical Society and sent to the Don’t lose out on your membership benefits, Subscriptions Department at No.4 Hamilton which include: Place, London W1J 7BQ, UK. • Your monthly subscription to AEROSPACE BACS Transfer: Pay by Bank Transfer (or by magazine BACS) into the Society’s bank account, quoting • Use of your RAeS post nominals as your name and membership number. Bank applicable details: • Over 400 global events yearly • Discounted rates for conferences Bank: HSBC plc • Online publications including Society News, Sort Code: 40-05-22 blogs and podcasts Account No: 01564641 • Involvement with your local branch BIC: MIDLGB2107K • Networking opportunities IBAN: GB52MIDL400522 01564641 • Support gaining Professional Registration • Opportunities & recognition with awards and medals • Professional development and support .. -

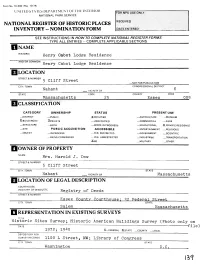

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATHS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Henry Cabot Lodge Residence AND/OR COMMON Henry Cabot Lodge Residence 5 Cliff Street .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Nahant VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Essex 009 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION -XNO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mrs. Harold J. Dow STREET & NUMBER 5 Cliff Street CITY, TOWN STATE Nahant VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Essex County Courthouse: ^2 Federal Street CITY, TOWN STATE Salem Massachusetts I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey; Historic American Buildings Survey (Photo only on DATE ————————————————————————————————————file) 1972; 19^0 X_FEDERAL 2LSTATE _COUNTY _J_OCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS 1100 L Street, NW; Library of Congress Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 3C ORIGINAL SITE X_QOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE This two-story, hip-roofed, white stucco-^covered, lavender- trimmed, brick villa is the only known extant residence associated with Henry Cabot Lodge. -

Mr. Tuck's File of Letters from Jennifer M

Mr. Tuck’s File of Letters from Jennifer M. Allocca’s research; additional notes by Dan Rothman The “Bulletin of the Essex Institute” (Volume XX. 1888. Salem, Mass. Printed 1889.) describes a September 1887 presentation to the Institute by Mr. J. D. Tuck, which provides additional information about the New Boston counterfeiters. https://books.google.com/books?id=BKQUAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA28&lpg=PA28 Joseph Dane Tuck (1817-1900) was a tailor who was born in Beverly, MA and died in that town. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Essex_Institute tells us that the Essex Institute (1848–1992) in Salem, Massachusetts, was “a literary, historical and scientific society.” It maintained a museum, library, historic houses; arranged educational programs; and issued numerous scholarly publications. In 1992 the institute merged with the Peabody Museum of Salem to form the Peabody Essex Museum. The correspondence in Mr. Tuck’s file gives us an interesting picture of how Boston-area bankers struggled with the expensive problem of counterfeit bills. Representatives of the banks whose notes had been counterfeited met to discuss what should be done. They feared that Mr. Peasley (or Peaslee) who had engraved the plates would flee when he learned of the arrest of the New Boston counterfeiters. The bankers knew that Stephen Burroughs, the most famous counterfeiter of his day, was busy producing paper currency in Stanstead, Quebec (in the Eastern Townships of Lower Canada), just a few miles north of the Vermont border. How could they apprehend him and place him “in the way to the Gallows”? They worried that at least one of the bailiffs they might send to Stanstead to collect evidence and arrest the counterfeiters was himself a member of the gang. -

John Davis Lodge Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft9c6007r1 Online items available Register of the John Davis Lodge papers Finding aid prepared by Grace Hawes and Katherine Reynolds Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 1998 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the John Davis Lodge 86005 1 papers Title: John Davis Lodge papers Date (inclusive): 1886-1987 Collection Number: 86005 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 288 manuscript boxes, 27 oversize boxes, 3 cubic foot boxes, 1 card file box, 3 album boxes, 121 envelopes, 2 sound cassettes, 1 sound tape reel, 1 sound disc(156.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, speeches and writings, dispatches, reports, memoranda, clippings, other printed matter, photographs, sound recordings, and motion picture film relating to the Republican Party, national and Connecticut politics, and American foreign relations, especially with Spain, Argentina and Switzerland. Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org. Creator: Lodge, John Davis, 1903-1985 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access Boxes 310-311 closed. The remainder of the collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1986. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], John Davis Lodge papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Alternate Forms Available Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1962-09-20

• enate Promises Force to Stop Red Advances In Cuba WASHINGTON (A'I - 'rwo Senate committees hung out a blunt ad I vance warning 1.0 the Communist world Wednesday ; The United States • will use force i( necessary to halt the advance of Communism in this ~ hemisphere. .. The Senate Foreign Relations and Armed Services committees The ·Weather unanimously approved II joint resolution stilling U.S. determination ; "To prevent by whatever means may be necessary, including the F.lr and c.... IIII'*' cM! I.V, nse of arms, the Ma rxist-Leninist regime in Cuba from extending by wilh hlths In tM 6ft. Plrtly lorce or threat of force its aggressive or subversive activities to any an douety .nd warlMr ItIIltht, plIrt of this hemisphere." I 011 ~ey House FOI'eign Affairs Com- [OI·t of a European power to ex Serving the State University of Io wa and the People of Iowa City tnlttec !l'cmbers were in consult~· lend its syslem into the Weslern Uon with the Sena~e groups III Hemisphere ; the Rio treaty of Established in 1868 Associated Pre:s Leased Wire and Wirephoto 10wa City, 10WII, Thursday, September 20, 1 2 hammering out the final language. 1947 which holds that an attack j Their commiltee was working on a on ~ne American stale would be similar resolulion_ ~II attack on all ; and the declara- The firm statement Or policy, ti(ln of loreign ministers at Punta expected to be approved Thursday del Este, Uruguay, last January. • by both houses of Congress and That declaration stated: "The sent lo Presidcnt Kennedy for his present government of Cuba has signature, also states U.S.