H-Diplo ROUNDTABLE XXII-30

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE UNITED STATES and the WORLD: SETTING LIMITS Jeane J

The Francis Boyer Lectures on Public Policy THE UNITED STATES AND THE WORLD: SETTING LIMITS Jeane J. Kirkpatrick American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research THE UNITED STATES AND THE WORLD: SETTING LIMITS The Francis Boyer Lectures on Public Policy THE UNITED STATES AND THE WORLD: SETTING LIMITS Jeane J. Kirkpatrick American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research ISBN 0-8447-1379-1 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 86-70364 ©1986 by the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Washington, D.C. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. "American Enterprise Institute" and @) are registered service marks of the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research. Printed in the United States of America American Enterprise Institute 1150 Seventeenth Street, N. W., Washington, D.C. 20036 THE FRANCIS BOYER LECTURES ON PUBLIC POLICY The American Enterprise Institute has initiated the Francis Boyer Lectures on Public Policy to examine the relationship between business and government and to develop contexts for their creative interaction. These lectures have been made possible by an endowment from the SmithKline Beck man Corporation in memory of Mr. Boyer, the late chairman of the board of the corporation. The lecture is given by an eminent thinker who has developed notable insights on one or more aspects of the relationship between the nation's private and public sectors. -

National Security Advisor SAIGON EMBASSY FILES KEPT by AMBASSADOR GRAHAM MARTIN: Copies Made for the NSC, 1963-1975 (1976)

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library & Museum National Security Advisor SAIGON EMBASSY FILES KEPT BY AMBASSADOR GRAHAM MARTIN: Copies Made for the NSC, 1963-1975 (1976) SUMMARY DESCRIPTION Copies of State Department telegrams and White House backchannel messages between U.S. ambassadors in Saigon and White House national security advisers, talking points for meetings with South Vietnamese officials, intelligence reports, drafts of peace agreements, and military status reports. Subjects include the Diem coup, the Paris peace negotiations, the fall of South Vietnam, and other U.S./South Vietnam relations topics, 1963 to 1975. QUANTITY 4.0 linear feet (ca. 8000 pages) DONOR Gerald R. Ford (accession number 82-73) ACCESS Open. The collection is administered under terms of the donor's deed of gift, a copy of which is available on request, and under National Archives and Records Administration general restrictions (36 CFR 1256). COPYRIGHT President Ford has donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. Prepared by Karen B. Holzhausen, November 1992; Revised March 2000 [s:\bin\findaid\nsc\saigon embassy files kept by ambassador graham martin.doc] [This finding aid, found at https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/guides/findingaid/ nsasaigon.asp, was slightly adapted on pp. 6-7 by the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in July 2018 to serve as a guide to the microfilm edition published by Primary Source Media.] 2 VIETNAM WAR CHRONOLOGY (Related to this collection) August 21, 1963 Ngo Dinh Nhu's forces attack Buddhist temples. -

Majority and Minority Leaders”, Available At

Majority and Minority Party Membership Other Resources Adapted from: “Majority and Minority Leaders”, www.senate.gov Available at: http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/briefing/Majority_Minority_Leaders.htm Majority and Minority Leaders Chapter 1: Introduction Chapter 2: Majority and Minority Leaders Chapter 3: Majority and Minority Whips (Assistant Floor Leaders) Chapter 4: Complete List of Majority and Minority Leaders Chapter 5: Longest-Serving Party Leaders Introduction The positions of party floor leader are not included in the Constitution but developed gradually in the 20th century. The first floor leaders were formally designated in 1920 (Democrats) and 1925 (Republicans). The Senate Republican and Democratic floor leaders are elected by the members of their party in the Senate at the beginning of each Congress. Depending on which party is in power, one serves as majority leader and the other as minority leader. The leaders serve as spokespersons for their parties' positions on issues. The majority leader schedules the daily legislative program and fashions the unanimous consent agreements that govern the time for debate. The majority leader has the right to be called upon first if several senators are seeking recognition by the presiding officer, which enables him to offer motions or amendments before any other senator. Majority and Minority Leaders Elected at the beginning of each Congress by members of their respective party conferences to represent them on the Senate floor, the majority and minority leaders serve as spokesmen for their parties' positions on the issues. The majority leader has also come to speak for the Senate as an institution. Working with the committee chairs and ranking members, the majority leader schedules business on the floor by calling bills from the calendar and keeps members of his party advised about the daily legislative program. -

FR: Kerry *Attachee\ Is Agenda and Draft Talking Points for Tonight's Freedom Forum Ninner. Chle Have Both Been Asked to Give 3

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu 5 !LS. TO: Senato~ Dole FR: Kerry *Attachee\_ is agenda and draft talking points for tonight's Freedom Forum Ninner. chle have both been asked to give 3 - 5 minutes of remarks at concl sion of dinner. *The Freedom Forum is part of a $700 million endowment established by the Gannett oragnization. It funds programs which explains the role of the media in our society ... Progams include a Media Studies Center at Columbia University and a First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt University. *In 1997 the Forum also plan on opening a "World Center" in Arlington which will include a "Newseum"--a museum highlighting the history of newspapers and the free press. At the dinner, Mr. Neuharth will also announce a new yearlong study of Congress and the media. Page 1 of 26 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu PAGE 1 FILE No . 677 01/05 '95 15:17 ID: SENT 6Y:Xerox Telecopier 7020 ; 1- 5-85 2: 10 PM ; 7035224882-+ :# 2 .... WOIUCJNG AGENDA Salute co tbe 'United State1 Senate and ttl New Le.aderahip January 5, 1995 7:4' Dinner Chimes/Guesta called t:o be seated 8:00 Invoca.tion Dr. RiohArd C. H&lvel"filon. Senate Chaplain 8:02 Charloa L. Overby· Welcome and Introduction of Fonner Senate Majority Leader and Master of Ceremonies Howard H. Baker Jr, (3 min.) 8:0S Howard H. Baker Jr. - hliToduetory Remarks and Jntrodu.ction of Cb.airman of The Freedom Forum Allen H, Ncuharth (5 min.) 8: 10 All= H. -

The BCCI Affair

The BCCI Affair A Report to the Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate by Senator John Kerry and Senator Hank Brown December 1992 102d Congress 2d Session Senate Print 102-140 This December 1992 document is the penultimate draft of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee report on the BCCI Affair. After it was released by the Committee, Sen. Hank Brown, reportedly acting at the behest of Henry Kissinger, pressed for the deletion of a few passages, particularly in Chapter 20 on "BCCI and Kissinger Associates." As a result, the final hardcopy version of the report, as published by the Government Printing Office, differs slightly from the Committee's softcopy version presented below. - Steven Aftergood Federation of American Scientists This report was originally made available on the website of the Federation of American Scientists. This version was compiled in PDF format by Public Intelligence. Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF INVESTIGATION ............................................................................... 21 THE ORIGIN AND EARLY YEARS OF BCCI .................................................................................................... 25 BCCI'S CRIMINALITY .................................................................................................................................. 49 BCCI'S RELATIONSHIP WITH FOREIGN GOVERNMENTS CENTRAL BANKS, AND INTERNATIONAL -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

Dictatorships & Double Standards

8/10/2021 Dictatorships & Double Standards - Jeane J. Kirkpatrick, Commentary Magazine NOVEMBER 1979 FEATURED Dictatorships & Double Standards The Classic Essay That Shaped Reagan's Foreign Policy by Jeane J. Kirkpatrick he failure of the Carter administration’s foreign policy is now clear to everyone except its architects, and T even they must entertain private doubts, from time to time, about a policy whose crowning achievement has been to lay the groundwork for a transfer of the Panama Canal from the United States to a swaggering Latin dictator of Castroite bent. In the thirty-odd months since the inauguration of Jimmy Carter as President there has occurred a dramatic Soviet military buildup, matched by the stagnation of American armed forces, and a dramatic extension of Soviet influence in the Horn of Africa, Afghanistan, Southern Africa, and the Caribbean, matched by a declining American position in all these areas. The U.S. has never tried so hard and failed so utterly to make and keep friends in the Third World. As if this were not bad enough, in the current year the United States has suffered two other major blows–in Iran and Nicaragua–of large and strategic significance. In each country, the Carter administration not only failed to prevent the undesired outcome, it actively collaborated in the replacement of moderate autocrats friendly to https://www.commentary.org/articles/jeane-kirkpatrick/dictatorships-double-standards/ 1/38 8/10/2021 Dictatorships & Double Standards - Jeane J. Kirkpatrick, Commentary Magazine American interests with less friendly autocrats of extremist persuasion. It is too soon to be certain about what kind of regime will ultimately emerge in either Iran or Nicaragua, but accumulating evidence suggests that things are as likely to get worse as to get better in both countries. -

Charles Bartlett Interviewer: Fred Holborn Date of Interview: January 6, 1965 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C

Charles Bartlett Oral History Interview – JFK #1, 1/6/1965 Administrative Information Creator: Charles Bartlett Interviewer: Fred Holborn Date of Interview: January 6, 1965 Place of Interview: Washington, D.C. Length: 91 pp. Biographical Note Bartlett, Washington correspondent for the Chattanooga Times from 1948 to 1962, columnist for the Chicago Daily News, and personal friend of John F. Kennedy (JFK), discusses his role in introducing Jacqueline Bouvier to JFK, JFK’s relationship with Lyndon Baines Johnson, and JFK’s Cabinet appointments, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed October 11, 1983, copyright of these materials has been assigned to United States Government. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. Direct your questions concerning copyright to the reference staff. -

Dead Last: the Public Memory of Warren G. Harding's Scandalous

Payne.1-19 11/13/08 3:02 PM Page 1 Questions Asked Democracy has no monuments. It strikes no medals. It bears the head of no man on a coin. —John Quincy Adams To enter into any serious historical criticism of these stories [regarding George Washington’s childhood] would be to break a butterfly. 1 —Henry Cabot Lodge Harding and the Log Cabin Myth Warren G. Harding’s story is an American myth gone wrong. As our twenty-ninth president, Harding occupied the office that stands at the symbolic center of American national identity.1 Harding’s biography should have easily slipped into American history and mythology when he died in office, on August 2, 1923. Having been born to a humble midwestern farm family, what better ending could there be to his story than death in the service of his nation? What stronger image could stand as a lasting tribute than grieving citizens lining the railroad tracks, as they had for Lincoln, Garfield, and McKinley, to view Har- ding’s body? The public grief that accompanied the passing of Harding’s burial train would seem to have foreshadowed a positive place in the national memory. Warren and Florence Harding were laid to rest in a classically designed marble mau- soleum in their hometown of Marion, Ohio, a mausoleum that was the last great memorial in the older style popular before the rise of presidential libraries. However, the near perfection Payne.1-19 11/13/08 3:02 PM Page 2 Dead Last of his political biography and his contemporary popularity did not follow him into history. -

Henry Cabot Lodge

1650 Copyright by CLP Research Partial Genealogy of the Lodges Main Political Affiliation: (of Massachusetts & Connecticut) 1763-83 1789-1823 Federalist ?? 1824-33 National Republican ?? 1700 1834-53 Whig ?? 1854- Republican 1750 Giles Lodge (1770-1852); (planter/merchant) (Emigrated from London, England to Santo Domingo, then Massachusetts, 1791) See Langdon of NH = Abigail Harris Langdon Genealogy (1776-1846) (possibly descended from John, son of John Langdon, 1608-97) 1800 10 Others John Ellerton Lodge (1807-62) (moved to New Orleans, 1824); (returned to Boston with fleet of merchant ships, 1835) (engaged in trade with China); (died in Washington state) See Cabot of MA = Anna Sophia Cabot Genealogy (1821-1901) Part I Henry Cabot Lodge (1850-1924) 1850 (MA house, 1880); (ally of Teddy Roosevelt) See Davis of MA (US House, 1887-93); (US Senate, 1893-1924; opponent of League of Nations) Genealogy Part I = Ann Cabot Mills Davis (1851-1914) See Davis of MA Constance Davis George Cabot Lodge Genealogy John Ellerton Lodge Cabot Lodge (1873-1909) Part I (1878-1942) (1872-after 1823) = Matilda Elizabeth Frelinghuysen Davis (1875-at least 1903) (Oriental art scholar) = Col. Augustus Peabody Gardner = Mary Connally (1885?-at least 1903) (1865-1918) Col. Henry Cabot Lodge Cmd. John Davis Lodge Helena Lodge 1900(MA senate, 1900-01) (from Canada) (US House, 1902-17) (1902-85); (Rep); (newspaper reporter) (1903-85); (Rep) (1905-at least 1970) (no children) (WWI/US Army) (MA house, 1933-36); (US Senate, 1937-44, 1947-53; (movie actor, 1930s-40s); -

Executive Order 13978 of January 18, 2021

6809 Federal Register Presidential Documents Vol. 86, No. 13 Friday, January 22, 2021 Title 3— Executive Order 13978 of January 18, 2021 The President Building the National Garden of American Heroes By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, it is hereby ordered as follows: Section 1. Background. In Executive Order 13934 of July 3, 2020 (Building and Rebuilding Monuments to American Heroes), I made it the policy of the United States to establish a statuary park named the National Garden of American Heroes (National Garden). To begin the process of building this new monument to our country’s greatness, I established the Interagency Task Force for Building and Rebuilding Monuments to American Heroes (Task Force) and directed its members to plan for construction of the National Garden. The Task Force has advised me it has completed the first phase of its work and is prepared to move forward. This order revises Executive Order 13934 and provides additional direction for the Task Force. Sec. 2. Purpose. The chronicles of our history show that America is a land of heroes. As I announced during my address at Mount Rushmore, the gates of a beautiful new garden will soon open to the public where the legends of America’s past will be remembered. The National Garden will be built to reflect the awesome splendor of our country’s timeless exceptionalism. It will be a place where citizens, young and old, can renew their vision of greatness and take up the challenge that I gave every American in my first address to Congress, to ‘‘[b]elieve in yourselves, believe in your future, and believe, once more, in America.’’ Across this Nation, belief in the greatness and goodness of America has come under attack in recent months and years by a dangerous anti-American extremism that seeks to dismantle our country’s history, institutions, and very identity. -

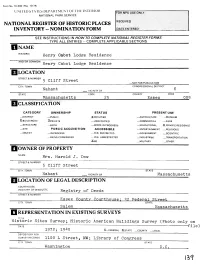

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATHS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Henry Cabot Lodge Residence AND/OR COMMON Henry Cabot Lodge Residence 5 Cliff Street .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Nahant VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Essex 009 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC XOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION -XNO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mrs. Harold J. Dow STREET & NUMBER 5 Cliff Street CITY, TOWN STATE Nahant VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Essex County Courthouse: ^2 Federal Street CITY, TOWN STATE Salem Massachusetts I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey; Historic American Buildings Survey (Photo only on DATE ————————————————————————————————————file) 1972; 19^0 X_FEDERAL 2LSTATE _COUNTY _J_OCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS 1100 L Street, NW; Library of Congress Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT -DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 3C ORIGINAL SITE X_QOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE This two-story, hip-roofed, white stucco-^covered, lavender- trimmed, brick villa is the only known extant residence associated with Henry Cabot Lodge.