Dead Last: the Public Memory of Warren G. Harding's Scandalous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Majority and Minority Leaders”, Available At

Majority and Minority Party Membership Other Resources Adapted from: “Majority and Minority Leaders”, www.senate.gov Available at: http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/briefing/Majority_Minority_Leaders.htm Majority and Minority Leaders Chapter 1: Introduction Chapter 2: Majority and Minority Leaders Chapter 3: Majority and Minority Whips (Assistant Floor Leaders) Chapter 4: Complete List of Majority and Minority Leaders Chapter 5: Longest-Serving Party Leaders Introduction The positions of party floor leader are not included in the Constitution but developed gradually in the 20th century. The first floor leaders were formally designated in 1920 (Democrats) and 1925 (Republicans). The Senate Republican and Democratic floor leaders are elected by the members of their party in the Senate at the beginning of each Congress. Depending on which party is in power, one serves as majority leader and the other as minority leader. The leaders serve as spokespersons for their parties' positions on issues. The majority leader schedules the daily legislative program and fashions the unanimous consent agreements that govern the time for debate. The majority leader has the right to be called upon first if several senators are seeking recognition by the presiding officer, which enables him to offer motions or amendments before any other senator. Majority and Minority Leaders Elected at the beginning of each Congress by members of their respective party conferences to represent them on the Senate floor, the majority and minority leaders serve as spokesmen for their parties' positions on the issues. The majority leader has also come to speak for the Senate as an institution. Working with the committee chairs and ranking members, the majority leader schedules business on the floor by calling bills from the calendar and keeps members of his party advised about the daily legislative program. -

FR: Kerry *Attachee\ Is Agenda and Draft Talking Points for Tonight's Freedom Forum Ninner. Chle Have Both Been Asked to Give 3

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu 5 !LS. TO: Senato~ Dole FR: Kerry *Attachee\_ is agenda and draft talking points for tonight's Freedom Forum Ninner. chle have both been asked to give 3 - 5 minutes of remarks at concl sion of dinner. *The Freedom Forum is part of a $700 million endowment established by the Gannett oragnization. It funds programs which explains the role of the media in our society ... Progams include a Media Studies Center at Columbia University and a First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt University. *In 1997 the Forum also plan on opening a "World Center" in Arlington which will include a "Newseum"--a museum highlighting the history of newspapers and the free press. At the dinner, Mr. Neuharth will also announce a new yearlong study of Congress and the media. Page 1 of 26 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu PAGE 1 FILE No . 677 01/05 '95 15:17 ID: SENT 6Y:Xerox Telecopier 7020 ; 1- 5-85 2: 10 PM ; 7035224882-+ :# 2 .... WOIUCJNG AGENDA Salute co tbe 'United State1 Senate and ttl New Le.aderahip January 5, 1995 7:4' Dinner Chimes/Guesta called t:o be seated 8:00 Invoca.tion Dr. RiohArd C. H&lvel"filon. Senate Chaplain 8:02 Charloa L. Overby· Welcome and Introduction of Fonner Senate Majority Leader and Master of Ceremonies Howard H. Baker Jr, (3 min.) 8:0S Howard H. Baker Jr. - hliToduetory Remarks and Jntrodu.ction of Cb.airman of The Freedom Forum Allen H, Ncuharth (5 min.) 8: 10 All= H. -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

Visit All of the Historic Sites and Museums! Ohiohistory.Org

Visit all of the historic sites and museums! ohiohistory.org ohiohistory.org • 800.686.6124 35. Fort Ancient Earthworks & Nature Preserve Museum/ Historic Buildings Mounds/ Monument/ Natural Area/ Gift Picnicking NORTHEAST Site Name Restrooms Average Visit 6123 State Route 350, Oregonia 45054 • 800.283.8904 v 190910 Visitor Center Open to Public Earthworks Gravesite Trails (miles) Shop (*shelter) Explore North America’s largest ancient hilltop enclosure, built 15. Custer Monument 1 Armstrong Air & Space Museum 2+ hours 2,000 years ago. Explore an on-site museum, recreated American State Route 646 and Chrisman Rd., New Rumley • 866.473.0417 Indian garden, and miles of hiking trails with scenic overlooks. 2 Cedar Bog Nature Preserve 1 2+ hours Visit the site of George Armstrong Custer’s birthplace and see the monument to the young soldier whose "Last Stand" made him a 36. Fort Hill Earthworks & Nature Preserve 3 Cooke-Dorn House 1 1+ hours household name. 13614 Fort Hill Rd., Hillsboro 45133 • 800.283.8905 Visit one of the best-preserved American Indian hilltop enclosures Ohio. of 4 Fallen Timbers Battlefield Memorial Park 1+ hours 16. Fort Laurens in North America and see an impressive variety of bedrock, soils, 11067 Fort Laurens Rd. NW (CR 102), Bolivar 44612 • 800.283.8914 flora and fauna. history fascinating and varied the life to bring help to 5 Fort Amanda Memorial Park 0.25 * 1+ hours Explore the site of Ohio’s only Revolutionary War fort, built in 1778 groups local these with work to proud is Connection 37. Harriet Beecher Stowe House History Ohio The communities. -

Niall Palmer

EnterText 1.1 NIALL PALMER “Muckfests and Revelries”: President Warren G. Harding in Fact and Fiction This article will assess the development of the posthumous reputation of President Warren Gamaliel Harding (1921-23) through an examination of key historical and literary texts in Harding historiography. The article will argue that the president’s image has been influenced by an unusual confluence of factors which have both warped history’s assessment of his administration and retarded efforts at revisionism. As a direct consequence, the stereotypical, deeply negative, portrait of Harding remains rooted in the nation’s consciousness and the “rehabilitation” afforded to many presidents by revisionist writers continues to be denied to the man still widely-regarded as the worst president of the twentieth century. “Historians,” Eugene Trani and David Wilson observed in 1977, “have not been gentle with Warren G. Harding.”1 In successive surveys of American political scientists, historians and journalists, undertaken to rank presidents by achievement, vision and leadership skills, the twenty-ninth president consistently comes last.2 The Chicago Sun- Times, publishing the findings of fifty-eight presidential historians and political scientists in November 1995, placed Warren Harding at the head of the list of “The Ten Worst” Niall Palmer: Muckfests and Revelries 155 EnterText 1.1 Presidents.3 A 1996 New York Times poll branded Harding an outright “failure,” alongside two presidents who presided over the pre-Civil War crisis, Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan. The academic merit and methodological underpinnings of such surveys are inevitably flawed. Nonetheless, in most cases, presidential status assessments are fluid, reflecting the fluctuations of contemporary opinion and occasional waves of academic revisionism. -

Who's Who in State Politics

M-.^m %f^,^, \.y'i>. ,„ J^":«s-^ jm^f' ;;v,>^v.^-v# ''MJ^-Z^^^^ -i,, mm^ i*'', 53* VK-J I't)^; ¥p%^, -r^^^n77% ^'^ ^^ » '^Jil^ JJ^^^%. m:-:^ <H^^ s n WHO'S WHO IN STATE POLITICS 1908 Vm A. PHILLIPS, \ P u h 1 i s h o (1 1) y PRACTICAL POLITICS 6 Beacon St. BOSTON. MASS. STSTELlBPlRYOFHiiaSUCSIMTS NOV 29 ly^ivi STATE HOUSE BOSTON Copyright, January, 1908 PRACTICAL POLITICS The Eastern Press Company, Boston 111 the preparation of tlii> xolume we have endeavored to.icJ.rn tlie names of the photographers h}- wHrfrni the various por- traits were made, and desire to give due credit to the following studios: Parsons, Adams; Litchtield, Arlington: Dunklee, Athol; Chiekering. Coiilin, Gliiies, Marceau, Notman, O'Xeill & Jordan, Purdy, Siegel, Boston; Bass, Brockton; Buttertield, Mc- Cabe, Cambridge: Moulton, Kitchburg; Phelps, Gloucester; Enterprise, Greentield; Fuller, McKeen, Haverhill: Demers & Son, Lawrence, Holyoke: Dexter, Ipswich; Loth- rop & Cunningham, Marion, Lowell; Thomp- son, Marblehead; Butman, Middleboro; Reed, New Bedford: Thompson, Orange; Skinner, Quincy: Ames, Salem; Benoit, Southbridge; Hudson, South Framingham; Bordeaux, Bosworth & Murphy, Spring- field; Webster, Waltham: Adams. VVhitins- ville; Fitton. Morrill, Schervee, Worcester. BAY STATE MEN IN WASHINGTON HENRY CABOT LODGE, Senator. LODGL:, IIKXRV CABOT. Republican, of Xahant. Was born in Boston, May 12, 1850; received a private scbool and collegi- ate education: was jj^^raduated from Harvard College in 1871; studied law at Harvard Law School and graduated in 1875, receiv- -

Team Players: Triumph and Tribulation on the Campaign Trail

residential campaigns that celebrate our freedom to choose a leader by election of the people are events P unique to our country. It is an expectant, exciting time – a promise kept by the Constitution for a better future. Rituals developed over time and became traditions of presidential hopefuls – the campaign slogans and songs, hundreds of speeches, thousands of handshakes, the countless miles of travel across the country to meet voters - all reported by the ever-present media. The candidate must do a balancing act as leader and entertainer to influence the American voters. Today the potential first spouse is expected to be involved in campaign issues, and her activities are as closely scrutinized as the candidate’s. However, these women haven’t always been an official part of the ritual contest. Campaigning for her husband’s run for the presidency is one of the biggest self-sacrifices a First Lady want-to-be can make. The commitment to the campaign and the road to election night are simultaneously exhilarating and exhausting. In the early social norms of this country, the political activities of a candidate’s wife were limited. Nineteenth-century wives could host public parties and accept social invitations. She might wave a handkerchief from a window during a “hurrah parade” or quietly listen to a campaign speech behind a closed door. She could delight the crowd by sending them a winsome smile from the front porch campaign of her own home. But she could not openly show knowledge of politics and she could not vote. As the wife of a newly-elected president, her media coverage consisted of the description of the lovely gown she wore to the Inaugural Ball. -

Modern First Ladies: Their Documentary Legacy. INSTITUTION National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 412 562 CS 216 046 AUTHOR Smith, Nancy Kegan, Comp.; Ryan, Mary C., Comp. TITLE Modern First Ladies: Their Documentary Legacy. INSTITUTION National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-911333-73-8 PUB DATE 1989-00-00 NOTE 189p.; Foreword by Don W. Wilson (Archivist of the United States). Introduction and Afterword by Lewis L. Gould. Published for the National Archives Trust Fund Board. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) -- Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Archives; *Authors; *Females; Modern History; Presidents of the United States; Primary Sources; Resource Materials; Social History; *United States History IDENTIFIERS *First Ladies (United States); *Personal Writing; Public Records; Social Power; Twentieth Century; Womens History ABSTRACT This collection of essays about the Presidential wives of the 20th century through Nancy Reagan. An exploration of the records of first ladies will elicit diverse insights about the historical impact of these women in their times. Interpretive theories that explain modern first ladies are still tentative and exploratory. The contention in the essays, however, is that whatever direction historical writing on presidential wives may follow, there is little question that the future role of first ladies is more likely to expand than to recede to the days of relatively silent and passive helpmates. Following a foreword and an introduction, essays in the collection and their authors are, as follows: "Meeting a New Century: The Papers of Four Twentieth-Century First Ladies" (Mary M. Wolf skill); "Not One to Stay at Home: The Papers of Lou Henry Hoover" (Dale C. -

Ohio Historic Preservation Organizations

Ohio Historic Preservation Organizations Prepared by Benjamin D. Rickey & Co. 593 South Fifth Street Columbus, Ohio 43206 May 2008 Ohio Historic Preservation Organizations Table of Contents List of Organizations by County 3 Certified Local Government List by Community 28 Designated Regional Heritage Areas 31 Statewide Preservation Organizations 32 Designated Ohio Scenic Byways 32 Designated Ohio Main Street Communities 32 1 Ohio Historic Preservation Organizations Introduction This list of historic preservation organizations in Ohio has been compiled from a variety of sources, including those provided by the Local History and the Ohio Historic Preservation Offices of the Ohio Historical Society, Heritage Ohio and Preservation Ohio (both statewide non-profit organizations). The author added information based on knowledge of the state and previous work with local and regional organizations. While every attempt was made to make the list comprehensive, it is likely that there are some omissions and the list should be updated periodically. 2 Ohio Historic Preservation Organizations Windsor Historical Society Adams 5471 State Route 322 Windsor, OH 44099 Manchester Historical Society PO Box 1 Athens Manchester, OH 45144 Phone: (937) 549-3888 Athens County Historical Society & Museum Allen 65 N. Court St. Athens, OH 45701 Downtown Lima (740) 592.2280 147 North Main Street Lima, Ohio 45801 Nelsonville Historic Square Arts District (419) 222-6045 Athens County Convention and Visitors [email protected] Bureau 667 East State Street Swiss Community Historical Society Athens, OH 45701 P.O. Box 5 Bluffton, OH 45817 Auglaize Ashland Belmont Ashland County Chapter-OGS Belmont County Chapter-OGS PO Box 681 PO Box 285 Ashland, OH 44805 Barnesville, OH 43713 Ashtabula Brown Ashtabula County Genealogical Society Ripley Museum Geneva Public Library PO Box 176 860 Sherman St. -

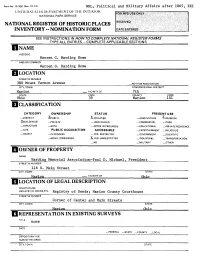

Iowner of Property

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Warren G. Harding Home AND/OR COMMON Warren G. Harding Home LOCATION STREETS NUMBER 380 Mount Vernon Avenue —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Marion . VICINITY OF 7th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Ohio 39 Marion 101 QCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT JKpUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE ^.MUSEUM JKBUILDING(S) _ PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE —BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS _ YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X.YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO _ MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME ____Harding Memorial Associaiton-Paul D. Michael, President STREET & NUMBER 116 S. Main Street CITY, TOWN STATE Marion VICINITY OF Ohio LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC Registry of Deeds; Marion County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER Corner of Center and Main Streets CITY, TOWN STATE Marion Ohio I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE none DATE -FEDERAL —STATE __COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE X.GOOD _RUINS X.ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Warren G. Harding Home sits at 380 Mt. Vernon Avenue on the north side of the street. The House was designed by the Hardings one year before their marriage. It is a two and one-half story clapboard structure painted green. The front porch runs across the front facade and the foundation is Indiana limestone. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

Ranking America's First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary Moves from 2 to 5 ; Jackie

For Immediate Release: Monday, September 29, 2003 Ranking America’s First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 nd Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary moves from 2 nd to 5 th ; Jackie Kennedy from 7 th th to 4 Mary Todd Lincoln Up From Usual Last Place Loudonville, NY - After the scrutiny of three expert opinion surveys over twenty years, Eleanor Roosevelt is still ranked first among all other women who have served as America’s First Ladies, according to a recent expert opinion poll conducted by the Siena (College) Research Institute (SRI). In other news, Mary Todd Lincoln (36 th ) has been bumped up from last place by Jane Pierce (38 th ) and Florence Harding (37 th ). The Siena Research Institute survey, conducted at approximate ten year intervals, asks history professors at America’s colleges and universities to rank each woman who has been a First Lady, on a scale of 1-5, five being excellent, in ten separate categories: *Background *Integrity *Intelligence *Courage *Value to the *Leadership *Being her own *Public image country woman *Accomplishments *Value to the President “It’s a tracking study,” explains Dr. Douglas Lonnstrom, Siena College professor of statistics and co-director of the First Ladies study with Thomas Kelly, Siena professor-emeritus of American studies. “This is our third run, and we can chart change over time.” Siena Research Institute is well known for its Survey of American Presidents, begun in 1982 during the Reagan Administration and continued during the terms of presidents George H. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush (http://www.siena.edu/sri/results/02AugPresidentsSurvey.htm ).