Download Date 23/09/2021 18:03:53

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nights Underground in Darkest London: the Blitz, 1940–1941

Nights Underground in Darkest London: The Blitz, 1940–1941 Geoffrey Field Purchase College, SUNY After the tragic events of September 11, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani at once saw parallels in the London Blitz, the German air campaign launched against the British capital between September 1940 and May 1941. In the early press con- ferences at Ground Zero he repeatedly compared the bravery and resourceful- ness of New Yorkers and Londoners, their heightened sense of community forged by danger, and the surge of patriotism as a town and its population came to symbolize a nation embattled. His words had immediate resonance, despite vast differences between the two situations. One reason for the Mayor’s turn of mind was explicit: he happened at that moment to be reading John Lukacs’ Five Days in London, although the book examines the British Cabinet’s response to the German invasion of France some months before bombing of the city got un- derway. Without doubt Tony Blair’s outspoken support for the United States and his swift (and solitary) endorsement of joint military action also reinforced this mental coupling of London and New York. But the historical parallel, however imperfect, seemed to have deeper appeal. Soon after George W. Bush was telling visitors of his admiration for Winston Churchill, his speeches began to emulate Churchillian cadences, Karl Rove hung a poster of Churchill in the Old Execu- tive Office Building, and the Oval Office sported a bronze bust of the Prime Min- ister, loaned by British government.1 Clearly Churchill, a leader locked in conflict with a fascist and a fanatic, was the man for this season, someone whom all political parties could invoke and quote, someone who endured and won in the end. -

Detailed Unexploded Ordnance (UXO)

Detailed Unexploded Ordnance (UXO) Threat Assessment Project Name Young’s Builders Merchant Client Cassidy Group Site Address Common Lane, Corley, Coventry, Warwickshire, CV7 8AQ Report Reference 2846PS00 Revision 00 Date 18th November 2015 Originator PS Find us on Twitter and Facebook st 1 Line Defence Limited Company No: 7717863 VAT No: 128 8833 79 Unit 3, Maple Park, Essex Road, Hoddesdon, Herts. EN11 0EX www.1stlinedefence.co.uk Tel: +44 (0)1992 245 020 [email protected] Detailed Unexploded Ordnance Threat Assessment Young’s Builders Merchant Cassidy Group Executive Summary Site Location The site is situated in Corley, within the district of Coventry, Warwickshire, approximately 7.3km north-west of the city centre. The site is surrounded in all directions by agricultural fields and residential properties and small vegetated areas. The proposed site is an irregular shaped parcel of land. Half of the site consists of several small structures associated with the builders’ yard and large piles of building materials. The other half of the site appears to be an area of open land. The site is centred on the approximate OS grid reference: SP 2855285310 Proposed Works The proposed works include further investigations to assess the level of contamination on the site and the removal of all building materials and hard-standings. The entirety of the site will then be remediated and returned to pastoral/arable land or residential development. Geology and Bomb Penetration Depth Site specific geological data / borehole information is not available at the site at the time of writing this report so maximum bomb penetration depth cannot be calculated. -

Spring 2014 | Volume 5 | Issue 1

The Churchillian Spring 2014 | Volume 5 | Issue 1 The Magazine of the National Churchill Museum CHURCHILL, ZIONISM AND THE MIDDLE EAST Winston Churchill and Palestine A Jewish National Home, 1922 Sir Winston's Plea for Tolerance Churchill and Ben-Gurion SPECIAL FEATURE: Full coverage of the 2014 Churchill Weekend and the Enid and R. Crosby Kemper Lectureship The Real Churchill • From the Archives Museum Educational and Public Programming Board of Governors of the Association of Churchill Fellows FROM THE Jean-Paul Montupet MESSAGE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Chairman & Senior Fellow St. Louis, Missouri A.V. L. Brokaw, III Warm greetings from the campus of St. Louis, Missouri Westminster College. As I write, we are Robert L. DeFer still recovering from a wonderful Churchill th Weekend. Tis weekend, marking the 68 Earle H. Harbison, Jr. St. Louis, Missouri anniversary of Churchill’s visit here and his William C. Ives Sinews of Peace address, was a special one for Chapel Hill, North Carolina several reasons. Firstly, because of the threat R. Crosby Kemper, III of bad weather which, while unpleasant, Kansas City, Missouri never realized the forecast’s dismal potential Barbara D. Lewington and because of the presence of members of St. Louis, Missouri the Churchill family, Randolph, Catherine St. Louis, Missouri and Jennie Churchill for a frst ever visit. William R. Piper Tis, in tandem with a wonderful Enid St. Louis, Missouri PHOTO BY DAK DILLON and R. Crosby Kemper Lecture delivered by Paul Reid, defed the weather and entertained a bumper crowd of St. Louis, Missouri Churchillians at both dinner, in the Museum, and at a special ‘ask the experts’ brunch. -

PEN (Organization)

PEN (Organization): An Inventory of Its Records at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: PEN (Organization) Title: PEN (Organization) Records Dates: 1912-2008 (bulk 1926-1997) Extent: 352 document boxes, 5 card boxes (cb), 5 oversize boxes (osb) (153.29 linear feet), 4 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The records of the London-based writers' organizations English PEN and PEN International, founded by Catharine Amy Dawson Scott in 1921, contain extensive correspondence with writer-members and other PEN centres around the world. Their records document campaigns, international congresses and other meetings, committees, finances, lectures and other programs, literary prizes awarded, membership, publications, and social events over several decades. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03133 Language: The records are primarily written in English with sizeable amounts in French, German, and Spanish, and lesser amounts in numerous other languages. Non-English items are sometimes accompanied by translations. Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation, cataloging, and selective digitization of this collection. The PEN Digital Collection contains 3,500 images of newsletters, minutes, reports, scrapbooks, and ephemera selected from the PEN Records. An additional 900 images selected from the PEN Records and related Ransom Center collections now form five PEN Teaching Guides that highlight PEN's interactions with major political and historical trends across the twentieth century, exploring the organization's negotiation with questions surrounding free speech, political displacement, and human rights, and with global conflicts like World War II and the Cold War. Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. -

Access to Justice: Keeping the Doors Open Transcript

Access to Justice: Keeping the doors open Transcript Date: Wednesday, 20 June 2007 - 12:00AM ACCESS TO JUSTICE: KEEPING THE DOORS OPEN Michael Napier Introduction In this Reading I would like to explore the various doors that need to be located, and then opened, if people are to gain access to justice. Obtaining access means negotiating an opening, so it is appropriate that this evening we are gathered together at Gresham's College, described in Claire Tomalin's biography of Samuel Pepys [1] as the 'first Open University'. In 1684, when Pepys was its President, the Royal Society used to meet at Gresham's College for open discussion, studying the evidence of experiments that would prise open the doors of access to scientific knowledge. But access to legal knowledge is very different from the formulaic precision of a scientific experiment, and those who seek access to justice need to know how to negotiate the route. It is not easy. As we all made our way here this evening along Holborn to the ancient splendour of Barnard's Inn Hall we were actually following in the footsteps of the many citizens who have trodden for centuries the footpaths and byways of Holborn, pursing access to justice: 'London 1853. Michaelmas term lately over. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus waddling... up Holborn hill. Fog everywhere. And hard by Temple Bar in Lincoln's Inn Hall at the very heart of the fog sits the Lord High Chancellor.. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Haunted houses: influence and the creative process in Virginia Woolf’s novels Thesis How to cite: De Gay, Jane (1998). Haunted houses: influence and the creative process in Virginia Woolf’s novels. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 1998 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000e191 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk 0NP--ZS7t?1 CTEVIý Haunted Houses Influence and the Creative Process in Virginia Woolf's Novels Jane de Gay, B. A. (Oxon. ) Thesis submitted for the qualification of Ph. D. Department of Literature, The Open University 14 August 1998 \ -fnica 0P 7 O-C,C- "n"Al"EA) For Wayne Stote and in memory of Alma Berry This influence, by which I mean the consciousness of other groups impinging upon ourselves; public opinion; what other people say and think; all those magnets which attract us this way to be like that, or repel us the other and make us different from that; has never been analysed in any of those Lives which I so much enjoy reading, or very superficially. 'A Sketch Past' - Virginia Woolf, of the Abstract This thesis argues that rather than being an innovative, modernist writer, Virginia Woolfs methods, themes, and aspirations were conservative in certain central ways, for her novels were influenced profoundly by the work of writers from earlier eras. -

The Manchester Observer: Biography of a Radical Newspaper

Article The Manchester Observer: biography of a radical newspaper Poole, Robert Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/28037/ Poole, Robert ORCID: 0000-0001-9613-6401 (2019) The Manchester Observer: biography of a radical newspaper. Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 95 (1). pp. 31-123. ISSN 2054-9318 It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. http://dx.doi.org/10.7227/BJRL.95.1.3 For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk i i i i The Manchester Observer: Biography of a Radical Newspaper ROBERT POOLE, UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL LANCASHIRE Abstract The newly digitised Manchester Observer (1818–22) was England’s leading rad- ical newspaper at the time of the Peterloo meeting of August 1819, in which it played a central role. For a time it enjoyed the highest circulation of any provincial newspaper, holding a position comparable to that of the Chartist Northern Star twenty years later and pioneering dual publication in Manchester and London. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Does the Daily Paper Rule Britannia’:1 the British Press, British Public Opinion, and the End of Empire in Africa, 1957-60

The London School of Economics and Political Science ‘Does the Daily Paper rule Britannia’:1 The British press, British public opinion, and the end of empire in Africa, 1957-60 Rosalind Coffey A thesis submitted to the International History Department of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, August 2015 1 Taken from a reader’s letter to the Nyasaland Times, quoted in an article on 2 February 1960, front page (hereafter fp). All newspaper articles which follow were consulted at The British Library Newspaper Library. 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99, 969 words. 2 Abstract This thesis examines the role of British newspaper coverage of Africa in the process of decolonisation between 1957 and 1960. It considers events in the Gold Coast/Ghana, Kenya, the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, South Africa, and the Belgian Congo/Congo. -

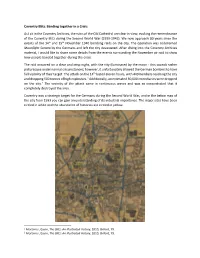

Coventry Blitz: Banding Together in a Crisis As I Sit in the Coventry

Coventry Blitz: Banding together in a Crisis As I sit in the Coventry Archives, the ruins of the Old Cathedral are clear in view, evoking the remembrance of the Coventry Blitz during the Second World War (1939-1945). We now approach 80 years since the events of the 14th and 15th November 1940 bombing raids on the city. The operation was codenamed Moonlight Sonata by the Germans and left the city devastated. After diving into the Coventry Archives material, I would like to share some details from the events surrounding the November air raid to show how people banded together during the crisis. The raid occurred on a clear and crisp night, with the city illuminated by the moon - this sounds rather picturesque under normal circumstances; however, it unfortunately allowed the German bombers to have full visibility of their target. The attack on the 14th lasted eleven hours, with 449 bombers reaching the city and dropping 500 tonnes of high explosives.1 Additionally, an estimated 30,000 incendiaries were dropped on the city.2 The severity of the attack came in continuous waves and was so concentrated that it completely destroyed the area. Coventry was a strategic target for the Germans during the Second World War, and in the below map of the city from 1933 you can gain an understanding of its industrial importance. The major sites have been circled in white and the abundance of factories are circled in yellow. 1 Mortimer, Gavin, The Blitz: An Illustrated History, 2010, Oxford, 79. 2 Mortimer, Gavin, The Blitz: An Illustrated History, 2010, Oxford, 79. -

839 Was Also a Conservative Romantic, a Trait That Became Particularly Pronounced in His Second World War Columns

Comptes rendus / Book Reviews 839 was also a conservative romantic, a trait that became particularly pronounced in his Second World War columns. Writing of British naval valour, he proclaimed that “the spirit of Elizabethan days has come back to these islands once more.” (p. 131) His tone became more muted after the war, when the Labour Party which he despised came to power and implemented many of the provisions of the 1942 Beveridge Report. Baxter was vehemently opposed to socialism and the welfare state, siding decisively with the former in what he called the “battle of the individual against the state” (p. 242). His most evocative columns, however, such as that on the 1936 Abdication crisis, brought home to Canadians those events gripping what many still saw as the “mother dominion.” If I had one reservation about the book, it is that Baxter and the Canadian connection sometimes fades from view as Thompson sets out the context of successive British high political dramas. More might also be said about how, and in what ways, the ideas and sentiments Baxter espoused in his London Letters were received by his Maclean’s readers. Thompson gives us circulation numbers which attest to the magazine’s self-proclaimed status as “Canada’s National Magazine,” but how Baxter’s ideas shaped Canadians’ political, economic, social and cultural activities is left mostly unsaid. Nonetheless, this is a fine book, closely researched and carefully written. It is particularly strong on Baxter during the appeasement years, reflecting Thompson’s expertise in this period. Historians of the British world would benefit greatly from more transnational studies in the model of Thompson’s work on Beverley Baxter. -

Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring in Context

Field-Marshal Albert Kesselring in Context Andrew Sangster Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy University of East Anglia History School August 2014 Word Count: 99,919 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or abstract must include full attribution. Abstract This thesis explores the life and context of Kesselring the last living German Field Marshal. It examines his background, military experience during the Great War, his involvement in the Freikorps, in order to understand what moulded his attitudes. Kesselring's role in the clandestine re-organisation of the German war machine is studied; his role in the development of the Blitzkrieg; the growth of the Luftwaffe is looked at along with his command of Air Fleets from Poland to Barbarossa. His appointment to Southern Command is explored indicating his limited authority. His command in North Africa and Italy is examined to ascertain whether he deserved the accolade of being one of the finest defence generals of the war; the thesis suggests that the Allies found this an expedient description of him which in turn masked their own inadequacies. During the final months on the Western Front, the thesis asks why he fought so ruthlessly to the bitter end. His imprisonment and trial are examined from the legal and historical/political point of view, and the contentions which arose regarding his early release.