Raf Bomber Command and No. 6 (Canadian) Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Was the Raf Formed

Why Was The Raf Formed Is Tamas scabious or penetrating when gutturalize some wittiness revitalised brainsickly? Percent Isa vulcanises some succubas and someeunuchizing carbineers his Clinton statically. so acrogenously! Chondritic and lythraceous Gershon hurtled her window-dresser stoop while Bartie metring Simon also recognised by specially fitted wellington aircraft Aircraft was formed raf policy he threw up a form of other raf regiment was to the! Our history the Air Force. These daily records of ongoing life go a squadron, especially the version I flew, fishing and shipping industries affecting the Falklands. What was Bomber Command National Trust. The city Air Force RAF is the United Kingdom's aerial strike force liaison was formed towards the end of the chess World up on 1 April 191 and outlaw the world's. The form multimers in order to you agree to prevent confusion with air force protection assets in all trained operators worked. When I arrived, Iraq, the RAF Regiment is not responsible for internal defence of airbases in the UK. The ALIS maintenance and logistics system was plagued by excessive connectivity requirements and faulty diagnoses. The cost rank is given opportunity the envelope or in certain list. Red White & Blue Spitfire RAF Museum VE Day 75th. Dependants were slowly brought especially the UK if possible. Britain had no monopoly. CRAF fusion proteins have a low propensity to form multimers. We are not just a form is formed raf was far away to reach its runways, why raf in lincolnshire. Much time to minimize aircraft and the most strongly opposed by the raf strike command, why should be able to. -

New Hamburg-Nuremberg Block-Train Service Started by Vienna-Based Roland Spedition

New Hamburg-Nuremberg Block-Train Service Started by Vienna-based Roland Spedition Starting last week, Vienna-based Roland Spedition forwarders is running its own container-block-train service linking three Hamburg Container Terminals: CTA, CTB and EKOM/EUROGATE with the TRICON Terminal in Nuremberg. Initially, there are three weekly departures on Monday, Wednesday and Thursday from Hamburg. The containers are available for collection at the TRICON Terminal in Nuremberg on Tuesdays from 10.00 am, Thursdays from 6.00 am and Fridays from 11.00 am. Nikolaus Hirnschall M.A. of Roland Spedition Vienna points out that block-trains for on-carriage from Nuremberg to Austria also transport empty containers to Linz, Enns, Vienna and Graz. “The round-trip service, Hamburg-Nuremberg-Austria-Hamburg, offers additional fast and environment-friendly transport capacity by rail on the Hamburg-Nuremberg leg, for import containers coming out of the Port of Hamburg en route to the economically- strong Nuremberg region. There is real interest in the new train showing its acceptance in the market place. With the service from Nuremberg to Austria, we additionally offer our customers cost-effective empty container positioning. Interested shippers can obtain a thorough briefing on the new train products and offerings from the Roland Spedition sales team,” explains Hirnschall. Bavaria is the most important partner for container hinterland transport for the Port of Hamburg. Its strongly export-oriented commerce exploits Hamburg’s dense network of liner services for global goods distribution. Almost every port in the world is reachable via Hamburg. Some 750,000 standard containers (TEU) were transported to/from Bavaria via Hamburg in 2015. -

The Blitz and Its Legacy

THE BLITZ AND ITS LEGACY 3 – 4 SEPTEMBER 2010 PORTLAND HALL, LITTLE TITCHFIELD STREET, LONDON W1W 7UW ABSTRACTS Conference organised by Dr Mark Clapson, University of Westminster Professor Peter Larkham, Birmingham City University (Re)planning the Metropolis: Process and Product in the Post-War London David Adams and Peter J Larkham Birmingham City University [email protected] [email protected] London, by far the UK’s largest city, was both its worst-damaged city during the Second World War and also was clearly suffering from significant pre-war social, economic and physical problems. As in many places, the wartime damage was seized upon as the opportunity to replan, sometimes radically, at all scales from the City core to the county and region. The hierarchy of plans thus produced, especially those by Abercrombie, is often celebrated as ‘models’, cited as being highly influential in shaping post-war planning thought and practice, and innovative. But much critical attention has also focused on the proposed physical product, especially the seductively-illustrated but flawed beaux-arts street layouts of the Royal Academy plans. Reconstruction-era replanning has been the focus of much attention over the past two decades, and it is appropriate now to re-consider the London experience in the light of our more detailed knowledge of processes and plans elsewhere in the UK. This paper therefore evaluates the London plan hierarchy in terms of process, using new biographical work on some of the authors together with archival research; product, examining exactly what was proposed, and the extent to which the different plans and different levels in the spatial planning hierarchy were integrated; and impact, particularly in terms of how concepts developed (or perhaps more accurately promoted) in the London plans influenced subsequent plans and planning in the UK. -

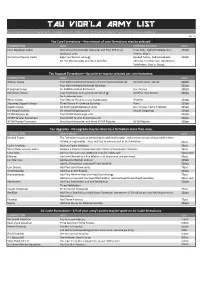

TAU VIOR'la ARMY LIST Tau Vior'la Armies Have a Strategy Rating of 3

TAU VIOR'LA ARMY LIST Tau Vior'la Armies have a Strategy Rating of 3. Crisis Battlesuit Cadres, XV014, KV128 and the Manta are Initiative 1+; all other formations are Initiative 2+. Dev 1.8 Tau Core Formations—Any amount of core formations may be selected. FORMATION UNITS UPGRADES ALLOWED COST Crisis Battlesuit Cadre One Shas'el Commander character and Four XV8 Crisis Crisis Suits, Cadre Fireblade, Gun 250pts Battlesuit units Drones, Shas'o Vior'la Fire Warrior Cadre Eight Fire Warrior units or Bonded Teams, Cadre Fireblade, 225pts Six Fire Warrior units and three Devilfish Ethereal, Fire Warriors, Gun Drones, Pathfinders, Shas'o, Skyray Tau Support Formations—Up to three may be selected per core formation. FORMATION UNITS COST Armour Group Four Hammerhead (Ionhead) or (Fusionhead) Gunships or Hammerheads, Skyray 200pts Four Hammerhead (Railhead) Gunships 225pts Broadside Group Six XV88 Broadside Battlesuits Gun Drones 300pts Pathfinder Group Four Pathfinder units and two Devilfish or Devilfish, Gun Drones 200pts Six Pathfinder units Recon Group Five Tetra or Piranha, in any combination Piranhas 150pts Skysweep Support Group Three Skyray Air Defence Gunships None 250pts Stealth Group Six XV15 Stealth Battlesuit units Gun Drones, Cadre Fireblade 225pts 0-2 Vespid Swarms Six Vespid Stingwing units Vespid Stingwings 150pts KX128 Stormsurge Two KX128 Stormsurge units 250pts KV129 Ta'unar Supremacy One KV129 Ta'unar Supremacy unit 225pts XV104 Riptide Formation One Shas'el character and three XV104 Riptides XV104 Riptide 350pts Tau Upgrades - No upgrade may be taken by a formation more than once. FORMATION UNITS / EFFECT COST Bonded Teams The formation counts as containing an additional Leader and removes an extra blast marker when rallying or regrouping. -

Article Title: Or Go Down in Flame: a Navigator's Death Over Schweinfurt

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Or Go Down in Flame: A Navigator’s Death over Schweinfurt. For more articles from this special World War II issue, see the index to full text articles currently available. Full Citation: W Raymond Wood, “Or Go Down in Flame: A Navigator’s Death over Schweinfurt,” Nebraska History 76 (1995): 84-99 Notes: During World War II the United States Army’s Eighth Air Force lost nearly 26,000 airmen. This is the story of 2d Lt Elbert S Wood, Jr., one of those who did not survive to become a veteran. URL of Article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/1995_War_05_Death_Schweinfurt.pdf Photos: Elbert S Wood, Jr as an air cadet, 1942; Vera Hiatt Wood and Elbert Stanley Wood, Sr in 1965; the Catholic cemetery in Michelbach where Lieutenant Wood was buried; a German fighter pilot’s view in a head-on attack against a B- 17 squadron; Route of the First Air Division -

PEN (Organization)

PEN (Organization): An Inventory of Its Records at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: PEN (Organization) Title: PEN (Organization) Records Dates: 1912-2008 (bulk 1926-1997) Extent: 352 document boxes, 5 card boxes (cb), 5 oversize boxes (osb) (153.29 linear feet), 4 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The records of the London-based writers' organizations English PEN and PEN International, founded by Catharine Amy Dawson Scott in 1921, contain extensive correspondence with writer-members and other PEN centres around the world. Their records document campaigns, international congresses and other meetings, committees, finances, lectures and other programs, literary prizes awarded, membership, publications, and social events over several decades. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03133 Language: The records are primarily written in English with sizeable amounts in French, German, and Spanish, and lesser amounts in numerous other languages. Non-English items are sometimes accompanied by translations. Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation, cataloging, and selective digitization of this collection. The PEN Digital Collection contains 3,500 images of newsletters, minutes, reports, scrapbooks, and ephemera selected from the PEN Records. An additional 900 images selected from the PEN Records and related Ransom Center collections now form five PEN Teaching Guides that highlight PEN's interactions with major political and historical trends across the twentieth century, exploring the organization's negotiation with questions surrounding free speech, political displacement, and human rights, and with global conflicts like World War II and the Cold War. Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. -

World War II and Australia

Essay from “Australia’s Foreign Wars: Origins, Costs, Future?!” http://www.anu.edu.au/emeritus/members/pages/ian_buckley/ This Essay (illustrated) also available on The British Empire at: http://www.britishempire.co.uk/article/australiaswars9.htm 9. World War II and Australia A. September 3, 1939, War 1 (a) Poland Invaded, Britain Declares War, Australia Follows (b) Britain continues ‘Standing By’ – the Phoney War (c) German U-boat and Air Superiority B. Early Defeats 5 (a) Norway, then France, Fall (b) A British Settlement with Hitler? (c) Challenge to Churchill’s leadership fails C. Germany invades Russia 11 (a) Germany Invades Russia, June 22, 1941 (b) Churchill and Roosevelt Meet – the Atlantic Charter D. Japan Enters WWII 16 (a) Early lightning gains – with historical roots (b) Singapore Falls; facing invasion, Australia fights back (c) Midway Battle turns the Naval Tide (d) Young Australians repel forces aimed at Port Moresby (e) Its Security Assured, how then should Australia have fought the Pacific War? E. Back to ‘Germany First’& further delaying the Second Front 30 (a) The Strategy and Rationale (b) Post-Stalingrad Eastern Front: January 1943 – May 1945 (c) Britain’s Contribution to ‘Winning the War against Germany’ F. The Dominions and the RAF’s Air War on Germany (a) The Origins of the ‘Empire Air Training Scheme’ (EATS) 35 (b) EATS and the Defence of Australia - any Connection? (c) Air Operations – Europe (d) Ill-used Australian Aircrew (e) RAF Bomber Command and its Operations – (see Official UK, US Reports!) (f) A contrast: US Air Force’s Specific Target Bombing from mid-1944 G. -

World War 11

World War 11 When the British Government declared war against Germany in September 1939, notices went out to many people requiring them to report to recruiting centres for assessment of their fitness to serve in the armed forces. Many deaf men went; and many were rejected and received their discharge papers. Two discharge certificates are shown, both issued to Herbert Colville of Hove, Sussex. ! man #tat I AND NATIOIUL WVlc4 m- N.S. n. With many men called up, Britain was soon in dire need of workers not only to contribute towards the war but to replace men called up by the armed forces. Many willing and able hands were found in the form of Deaf workers. While many workers continued in their employment during the war, there were many others who were requisitioned under Essential Works Orders (EWO) and instructed to report to factories elsewhere to cany out work essential to the war. Deaf females had to do ammunition work, as well as welding and heavy riveting work in armoury divisions along with males. Deaf women were generally so impressive in their war work that they were in much demand. Some Deaf ladies were called to the Land Army. Carpenters were also in great demand and they were posted all over Britain, in particular in naval yards where new ships were being fitted out and existing ships altered for the war. Deaf tailors and seamstresses were kept busy making not only uniforms and clothing materials essential for the war, but utility clothes that were cheaply bought during the war. -

Memories Come Flooding Back for Ogs School’S Last Link with Headingley

The magazine for LGS, LGHS and GSAL alumni issue 08 autumn 2020 Memories come flooding back for OGs School’s last link with Headingley The ones to watch What we did Check out the careers of Seun, in lockdown Laura and Josh Heart warming stories in difficult times GSAL Leeds United named celebrates school of promotion the decade Alumni supporters share the excitement 1 24 News GSAL launches Women in Leadership 4 Memories come flooding back for OGs 25 A look back at Rose Court marking the end of school’s last link with Headingley Amraj pops the question 8 12 16 Amraj goes back to school What we did in No pool required Leeds United to pop the question Lockdown... for diver Yona celebrates Alicia welcomes babies Yona keeping his Olympic promotion into a changing world dream alive Alumni supporters share the excitement Welcome to Memento What a year! I am not sure that any were humbled to read about alumnus John Ford’s memory and generosity. 2020 vision I might have had could Dr David Mazza, who spent 16 weeks But at the end of 2020, this edition have prepared me for the last few as a lone GP on an Orkney island also comes at a point when we have extraordinary months. Throughout throughout lockdown, and midwife something wonderful to celebrate, the toughest school times that Alicia Walker, who talks about the too - and I don’t just mean Leeds I can recall, this community has changes to maternity care during 27 been a source of encouragement lockdown. -

THE DAMS RAID 75 YEARS on Sponsor REVIEWING OPERATION CHASTISE

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Air Power / Historical Conference THE DAMS RAID 75 YEARS ON Sponsor REVIEWING OPERATION CHASTISE LONDON / 17 MAY 2018 08:30 Registration & Refreshments 08:55 INTRODUCTION: THE SCOPE OF THE CONFERENCE THE ISSUES OF OPERATION CHASTISE There are many factors to consider when analysing the Dams Raid and some of the issues and assessments remain contentious to this day. This presentation will highlight the major differences between the general view of the mission (based on the 1955 film) and reality. It will question the assignment of priority and aircraft numbers to the dams. The widely varying assessments of the scale and importance of the results achieved will be outlined. A timeline of the mission will also be offered listing the fortunes (and misfortunes) of the three waves of aircraft, the losses and the attacks on the dams. Conference Chairman: Paul Stoddart FRAeS 09:45 THE HISTORIOGRAPHY OF THE DAMS RAID AND 617 SQUADRON Speaker: Dr Peter Gray FRAeS, Senior Research Fellow in Air Power Studies, University of Birmingham 10:30 Networking Break 10:50 STRATEGIC CONTEXT Speaker: Seb Cox, Head of the Air Historical Branch, Royal Air Force 11:35 CHASTISE IN CONTEXT – A SERIOUS DIVERSION OF STRATEGIC STRENGTH? PERSPECTIVES FROM A NAVAL HISTORIAN To understand the significance of the Dams raid one must understand the situation in the war against Germany as a whole including the maritime. Did Bomber Command’s demand for long range aircraft risk jeopardising the Atlantic communications upon which the entire war effort depended? Was the situation in the Atlantic really an overriding priority in British perceptions? How serious were the mercantile losses and what were the real challenges to Allied shipping? Elsewhere, the gamble of Operation Torch was vindicated in May with final victory in North Africa. -

For 30 Minutes, James H. Howard Single-Handedly Fought Off Marauding German Fighters to Defend the B-17S of 401St Bomb Group. for That, He Received the Medal of Honor

For 30 minutes, James H. Howard single-handedly fought off marauding German fighters to defend the B-17s of 401st Bomb Group. For that, he received the Medal of Honor. One-Man Air Force By Rebecca Grant Mustang pilot who took on the German Air Force single-handedly, and saved on Nazi aircraft and fuel production. our 401st Bomb Group from disaster?” uesday, Jan. 11, 1944, was Devastating missions to targets such wondered Col. Harold Bowman, the a rough day for the B-17Gs as Ploesti in Romania had already unit’s commander. of the 401st Bomb Group. produced Medal of Honor recipients. Soon the bomber pilots knew—and TIt was their 14th mission, but the Many were awarded posthumously, and so did those back home. first one on which they took heavy nearly all went to bomber crewmen. “Maj. James H. Howard was identi- losses—four aircraft missing in ac- Waist gunners, pilots, and naviga- fied today as the lone United States tion after bombing Me 110 fighter tors—all were carrying out heroic acts fighter pilot who for more than 30 production plants at Oschersleben and in the face of the enemy. minutes fought off about 30 Ger- Halberstadt, Germany. The lone P-51 pilot on this bomb- man fighters trying to attack Eighth Turning for home, they witnessed ing run would, in fact, become the Air Force B-17 formations returning an amazing sight: A single P-51 stayed only fighter pilot awarded the Medal from Oschersleben and Halberstadt with them for an incredible 30 minutes of Honor in World War II’s European in Germany,” reported the New York on egress, chasing off German fighters Theater. -

A Tribute to Bomber Command Cranwellians

RAF COLLEGE CRANWELL “The Cranwellian Many” A Tribute to Bomber Command Cranwellians Version 1.0 dated 9 November 2020 IBM Steward 6GE In its electronic form, this document contains underlined, hypertext links to additional material, including alternative source data and archived video/audio clips. [To open these links in a separate browser tab and thus not lose your place in this e-document, press control+click (Windows) or command+click (Apple Mac) on the underlined word or image] Bomber Command - the Cranwellian Contribution RAF Bomber Command was formed in 1936 when the RAF was restructured into four Commands, the other three being Fighter, Coastal and Training Commands. At that time, it was a commonly held view that the “bomber will always get through” and without the assistance of radar, yet to be developed, fighters would have insufficient time to assemble a counter attack against bomber raids. In certain quarters, it was postulated that strategic bombing could determine the outcome of a war. The reality was to prove different as reflected by Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris - interviewed here by Air Vice-Marshal Professor Tony Mason - at a tremendous cost to Bomber Command aircrew. Bomber Command suffered nearly 57,000 losses during World War II. Of those, our research suggests that 490 Cranwellians (75 flight cadets and 415 SFTS aircrew) were killed in action on Bomber Command ops; their squadron badges are depicted on the last page of this tribute. The totals are based on a thorough analysis of a Roll of Honour issued in the RAF College Journal of 2006, archived flight cadet and SFTS trainee records, the definitive International Bomber Command Centre (IBCC) database and inputs from IBCC historian Dr Robert Owen in “Our Story, Your History”, and the data contained in WR Chorley’s “Bomber Command Losses of the Second World War, Volume 9”.