University Microfilms. a XER0K Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Identification of Radicals in the British Parliament

1 HANSEN 0001 040227 名城論叢 2004年3月 31 THE IDENTIFICATION OF ‘RADICALS’ IN THE BRITISH PARLIAMENT, 1906-1914 P.HANSEN INTRODUCTION This article aims to identify the existence of a little known group of minority opinion in British society during the Edwardian Age. It is an attempt to define who the British Radicals were in the parliaments during the years immediately preceding the Great War. Though some were particularly interested in the foreign policy matters of the time,it must be borne in mind that most confined their energies to promoting the Liberal campaign for domestic welfare issues. Those considered or contemporaneously labelled as ‘Radicals’held ‘leftwing’views, being politically somewhat just left of centre. They were not revolutionaries or communists. They wanted change through reforms carried out in a democratic manner. Their failure to carry out changes on a significant scale was a major reason for the decline of the Liberals,and the rise and ultimate success of the Labour Party. Indeed, following the First World War, many Radicals defected from the Liberal Party to join Labour. With regard to historiography,it can be stated that the activities of British Radicals from the turn of the century to the outbreak of the First World War were the subject of interest to the most famous British historian of the second half of the 20century, A. J. P. Taylor. He wrote of them in his work The Troublemakers based on his Ford Lectures of 1956. By the early 1970s’A.J.A.Morris had established a reputation in the field with his book Radicalism Against War, 1906-1914 (1972),and a further publication of which he was editor,Edwardian Radical- ism 1900-1914 (1974). -

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This Collection Was the Gift of Howard J

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This collection was the gift of Howard J. Garber to Case Western Reserve University from 1979 to 1993. Dr. Howard Garber, who donated the materials in the Howard J. Garber Manuscript Collection, is a former Clevelander and alumnus of Case Western Reserve University. Between 1979 and 1993, Dr. Garber donated over 2,000 autograph letters, documents and books to the Department of Special Collections. Dr. Garber's interest in history, particularly British royalty led to his affinity for collecting manuscripts. The collection focuses primarily on political, historical and literary figures in Great Britain and includes signatures of all the Prime Ministers and First Lords of the Treasury. Many interesting items can be found in the collection, including letters from Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning Thomas Hardy, Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, King George III, and Virginia Woolf. Descriptions of the Garber Collection books containing autographs and tipped-in letters can be found in the online catalog. Box 1 [oversize location noted in description] Abbott, Charles (1762-1832) English Jurist. • ALS, 1 p., n.d., n.p., to ? A'Beckett, Gilbert A. (1811-1856) Comic Writer. • ALS, 3p., April 7, 1848, Mount Temple, to Morris Barnett. Abercrombie, Lascelles. (1881-1938) Poet and Literary Critic. • A.L.S., 1 p., March 5, n.y., Sheffield, to M----? & Hughes. Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon (1784-1860) British Prime Minister. • ALS, 1 p., June 8, 1827, n.p., to Augustous John Fischer. • ANS, 1 p., August 9, 1839, n.p., to Mr. Wright. • ALS, 1 p., January 10, 1853, London, to Cosmos Innes. -

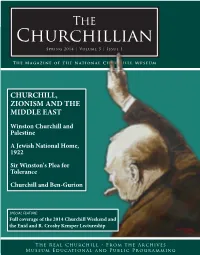

Spring 2014 | Volume 5 | Issue 1

The Churchillian Spring 2014 | Volume 5 | Issue 1 The Magazine of the National Churchill Museum CHURCHILL, ZIONISM AND THE MIDDLE EAST Winston Churchill and Palestine A Jewish National Home, 1922 Sir Winston's Plea for Tolerance Churchill and Ben-Gurion SPECIAL FEATURE: Full coverage of the 2014 Churchill Weekend and the Enid and R. Crosby Kemper Lectureship The Real Churchill • From the Archives Museum Educational and Public Programming Board of Governors of the Association of Churchill Fellows FROM THE Jean-Paul Montupet MESSAGE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Chairman & Senior Fellow St. Louis, Missouri A.V. L. Brokaw, III Warm greetings from the campus of St. Louis, Missouri Westminster College. As I write, we are Robert L. DeFer still recovering from a wonderful Churchill th Weekend. Tis weekend, marking the 68 Earle H. Harbison, Jr. St. Louis, Missouri anniversary of Churchill’s visit here and his William C. Ives Sinews of Peace address, was a special one for Chapel Hill, North Carolina several reasons. Firstly, because of the threat R. Crosby Kemper, III of bad weather which, while unpleasant, Kansas City, Missouri never realized the forecast’s dismal potential Barbara D. Lewington and because of the presence of members of St. Louis, Missouri the Churchill family, Randolph, Catherine St. Louis, Missouri and Jennie Churchill for a frst ever visit. William R. Piper Tis, in tandem with a wonderful Enid St. Louis, Missouri PHOTO BY DAK DILLON and R. Crosby Kemper Lecture delivered by Paul Reid, defed the weather and entertained a bumper crowd of St. Louis, Missouri Churchillians at both dinner, in the Museum, and at a special ‘ask the experts’ brunch. -

David Lloyd George and Temperance Reform Philip A

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 1980 The ac use of sobriety : David Lloyd George and temperance reform Philip A. Krinsky Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation Krinsky, Philip A., "The cause of sobriety : David Lloyd George and temperance reform" (1980). Honors Theses. Paper 594. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND LIBRARIES llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll/11111 3 3082 01 028 9899 - The Cause of Sobriety: David Lloyd George and Temperance Reform Philip A. Krinsky Contents I. Introduction: 1890 l II. Attack on Misery: 1890-1905 6 III. Effective Legislation: 1906-1918 16 IV. The Aftermath: 1918 to Present 34 Notes 40 Bibliographical Essay 47 Temperance was a major British issue until after World War I. Excessive drunkenness, not alcoholism per se, was the primary concern of the two parliamentary parties. When Lloyd George entered Parliament the two major parties were the Liberals and the Conservatives. Temperance was neither a problem that Parliament sought to~;;lv~~ nor the single issue of Lloyd George's public career. Rather, temperance remained within a flux of political squabbling between the two parties and even among the respective blocs within each Party. Inevitably, compromises had to be made between the dissenting factions. The major temperance controversy in Parliament was the issue of compensation. Both Parties agreed that the problem of excessive drunkenness was rooted in the excessive number of public houses throughout Britain. -

(I) Sir Cuthbert Headlam: the Second Phase Cuthbert Morley Headlam Came from a Minor Gentry Family Which Had Its Roots in North Yorkshire and South County Durham

2 The Headlam Diaries text, and its value as a source. Together, these furnish the context in which the diary can be used and understood. (i) Sir Cuthbert Headlam: the Second Phase Cuthbert Morley Headlam came from a minor gentry family which had its roots in north Yorkshire and south County Durham. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the Headlams were extensively involved in the respectable professions of the armed services, the Established Church, the law, and public school and university education. Born on 27 April 1876 into a cadet branch, Cuthbert was educated at King's School, Canterbury, and at Magdalen College, Oxford. He had no inherited income to fall back upon, and throughout his life had to make his own living. On leaving Oxford in 1897 he accepted the offer of a Clerkship in the House of Lords. Here he remained until 1924, with the interruption of service on the Western Front between 1915 and 1918 during which he rose to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel on the General Staff. The Lords' clerkship proved to be a dreary dead end, but after his marriage to Beatrice Crawley in 1904 he was dependent upon its salary. However, in the early 1920s the development of an independent income from journalistic and business activities at last made venturing into politics a possibility, albeit a risky one. Even then, Headlam had not the surplus wealth necessary to fund the large annual subscription usually required from their candidates by Conservative Associations in safe seats. Throughout his career he was to find himself rejected on these grounds in favour of less able men, an experience which contributed to his growing embitterment by the mid-1930s. -

Liberals in Coalition

For the study of Liberal, SDP and Issue 72 / Autumn 2011 / £10.00 Liberal Democrat history Journal of LiberalHI ST O R Y Liberals in coalition Vernon Bogdanor Riding the tiger The Liberal experience of coalition government Ian Cawood A ‘distinction without a difference’? Liberal Unionists and Conservatives Kenneth O. Morgan Liberals in coalition, 1916–1922 David Dutton Liberalism and the National Government, 1931–1940 Matt Cole ‘Be careful what you wish for’ Lessons of the Lib–Lab Pact Liberal Democrat History Group 2 Journal of Liberal History 72 Autumn 2011 new book from tHe History Group for details, see back page Journal of Liberal History issue 72: Autumn 2011 The Journal of Liberal History is published quarterly by the Liberal Democrat History Group. ISSN 1479-9642 Riding the tiger: the Liberal experience of 4 Editor: Duncan Brack coalition government Deputy Editor: Tom Kiehl Assistant Editor: Siobhan Vitelli Vernon Bogdanor introduces this special issue of the Journal Biographies Editor: Robert Ingham Reviews Editor: Dr Eugenio Biagini Coalition before 1886 10 Contributing Editors: Graham Lippiatt, Tony Little, York Membery Whigs, Peelites and Liberals: Angus Hawkins examines coalitions before 1886 Patrons A ‘distinction without a difference’? 14 Dr Eugenio Biagini; Professor Michael Freeden; Ian Cawood analyses how the Liberal Unionists maintained a distinctive Professor John Vincent identity from their Conservative allies, until coalition in 1895 Editorial Board The coalition of 1915–1916 26 Dr Malcolm Baines; Dr Roy Douglas; Dr Barry Doyle; Prelude to disaster: Ian Packer examines the Asquith coalition of 1915–16, Dr David Dutton; Prof. David Gowland; Prof. Richard which brought to an end the last solely Liberal government Grayson; Dr Michael Hart; Peter Hellyer; Dr J. -

The Manchester Observer: Biography of a Radical Newspaper

Article The Manchester Observer: biography of a radical newspaper Poole, Robert Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/28037/ Poole, Robert ORCID: 0000-0001-9613-6401 (2019) The Manchester Observer: biography of a radical newspaper. Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 95 (1). pp. 31-123. ISSN 2054-9318 It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. http://dx.doi.org/10.7227/BJRL.95.1.3 For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk i i i i The Manchester Observer: Biography of a Radical Newspaper ROBERT POOLE, UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL LANCASHIRE Abstract The newly digitised Manchester Observer (1818–22) was England’s leading rad- ical newspaper at the time of the Peterloo meeting of August 1819, in which it played a central role. For a time it enjoyed the highest circulation of any provincial newspaper, holding a position comparable to that of the Chartist Northern Star twenty years later and pioneering dual publication in Manchester and London. -

School of Oriental and African Studies)

BRITISH ATTITUDES T 0 INDIAN NATIONALISM 1922-1935 by Pillarisetti Sudhir (School of Oriental and African Studies) A thesis submitted to the University of London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1984 ProQuest Number: 11010472 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010472 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT This thesis is essentially an analysis of British attitudes towards Indian nationalism between 1922 and 1935. It rests upon the argument that attitudes created paradigms of perception which condi tioned responses to events and situations and thus helped to shape the contours of British policy in India. Although resistant to change, attitudes could be and were altered and the consequent para digm shift facilitated political change. Books, pamphlets, periodicals, newspapers, private papers of individuals, official records, and the records of some interest groups have been examined to re-create, as far as possible, the structure of beliefs and opinions that existed in Britain with re gard to Indian nationalism and its more concrete manifestations, and to discover the social, political, economic and intellectual roots of the beliefs and opinions. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

POST OFFICE LONDON MAJ-MAR Majendierev.Severne Andrew .Ashurst,M.A

2178 MAJ-MAR POST OFFICE LONDON MAJ-MAR MajendieRev.Severne Andrew .Ashurst,M.A. 2 St. Malony William Alfred. 2 St. George's square SW Manners Dowager Lany, 17 Oadogan square SW March Miss, 57 Bedford gardens, Kensington W Katharine's precincts, Regent's park NW Malpas John, 71 Hungerford road N Manners Lady Victoria, 12 Chelsea embank- March Miss, 9 Cadogan mansions, Sloane sq SW :Majendie Misses, 32 Marlborough hill NW Malpas Miss, 70 St. George's road SW ment gardens, Chelsea SW March Sydney, 64 Glebe plaCP., Chelsea SW - Majid Syed abdul, LL.D.l Elm court, Temple E C Malpas Miss, 15 Victoria square SW Manners Frederick, 6 Beaumanor manRions, Marchamley Lord, P.C. 29 Prince's gardens SW: Majolier Mrs. 20 Bramham gardens SW Malschinger Charles. 20 La"'iord road NW Queen's road, Bayswater W & Reform & Devonshire clubs SW Major Col. Napoleon Bisdee, 2 addison gdns W Maltby Lieut. Gerald Rivers. M.v.o., R.N. 54 !:;t. Manners John Robert, 3 Hare court, Temple E C Marchant Charles,16 Cllfton gardens W Major George, 22 Connaught square W George's square, Pimlico SW Manners Stepney, 47 Porchester road W Marchant Ernest William. 188 & 189 Strand WC Major George, 54 Peun road, Holloway N Maltby Rev. Etlward Seeker, B.A. St. Mary's Manners Walt.Evelyn,12Chesterfieldst.MayfairW & 3 St. Andrew'~ road, Stamford hill N Major Mrs. 48 Comeragh road, West KensingtnW Tower, Erlam road South Bermondsey SE Manners-SuttonFras.H. a.4 Down st.PiccadillyW Marchant James Robert Vernam, 3 Paper bldgs. Major Thomas, 35 Oardozo road N Maltby Hy. -

Progressive Politics

the Language of Progressive Politics in Modern Britain Emily Robinson The Language of Progressive Politics in Modern Britain Emily Robinson The Language of Progressive Politics in Modern Britain Emily Robinson Department of Politics University of Sussex Brighton, United Kingdom ISBN 978-1-137-50661-0 ISBN 978-1-137-50664-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-50664-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016963256 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identified as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the pub- lisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

PARLIAMENTARY DIRECTORY. 5 - Oavies Matthew Lewis Vaughan

DIRECTORY.] PARLIAMENTARY DIRECTORY. 5 - Oavies Matthew Lewis Vaughan ...... Cardiganshire .••..•.••.•• 17 Hyde Park gardens W; Brooks's club SW; & Tan-y• bwlch, Aberystwith Davies Thomas Hart-,see Hart-Davies Davies Timothy .....•.......••.....•...... Fulham ......... ...... ... ... National Liberal club SW; & Pantycelyn, Oakhill road, East Putney t!W Davies Sir William How ell ... ...... ... Bri,tol (South Division) 4 Whitehall court SW; National Liberal club SW; & Down house, Stoke Bishop, Bristol Delany William ........•.....•.....•...... Queen's Co. ( Ossm-y Div.) Tullamor~>, Ireland Devlin Joseph ..............•........•...... Belfast (West)............ 39 Upper O'Connell street, Dublin Dewar Arthur, K.C .....•.••.•••••..•..•..• Edinburgh (South Div.) Reform & National Liberal clubs SW; & 24 Walker street, Edinburgh Dewar Sir John Alexander, bart .....• Inverne.~s-shire .......•.••• Reform club SW Dickinson "\Villougb by Hyett .••.....• St. Pan(JJ•as (N. Div.) .•• Fountain court, Temple EC; 41 & 42 Parliament street SW ; 51 Campden hill road W; & New University & National Liberal clubs SW Dickson-Poynder Sir John Poynder, Wiltshire (N. W. or 8 Chesterfield gardens, Mayfair W ; Marlborough club bart., D.S.O Chippenham Division) SW; Turf club W ; Hartham park, Corsham, Wilts ; & Hilmarton manor, Calne Dilke Rt. Hon. Sir Charles Went Gloucester (Forest of 76 Sloane street SW; Refurm,National Liberal & Bm-ling worth, bart., LL.lll Dean Division) ton Fine Arts clubs SW ; Dockett Eddy, Shepperton: & Pyrford, near Woking Dill on John ................................. Mayo County (East) ..• Bath club W; & North Great George's street, Dublin Dixon· Hartland Sir Fredk. Dixon, bart Mirldlesr.x( UxbridgBDiv 14 Chesham place SW ; Carlton club SW; Ashley manor, ision) near Cheltenham ; & Middleton manor, near Bognor Dobson Thomas "\Villiam .............. Plymouth ................. Xational Liberal club SW; & 25 Baskerville road, Wands worth common SW Donelan Capt.