The Manchester Observer: Biography of a Radical Newspaper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Did Ordinary People Win the Right to Vote? Y8 Extended History Project

How did ordinary people win the right to vote? Y8 Extended History Project History 1.What were the problems with the way people voted in the 1800s? Rotten Burroughs and open ballots History Throughout this project we are going to look at the changes in Britain’s democracy through the eyes of four groups of people: A working- A working-class Middle-class Tory landowner class woman radical (factory businessman (MP) worker) History The price of bread is too high, I employ hundreds of people in our rent has gone up again and my factories, I pay taxes and my we are starving. I need an MP factories have made Britain very who can make Britain fairer, so I wealthy. So why don’t I get a say don’t starve. in the government? A working- Middle-class class woman businessman It is our natural right to have a Our political system has worked say in who governs us. The perfectly and has lasted for working men of Britain are what centuries. Only wealthy keep this country going and landowners should vote because deserve recognition. If we do not we have greater interest in Britain get what is our right, then we doing well. These working classes should revolt! are too uneducated to have a say. A working-class Tory landowner radical (factory (MP) worker) History 1b) History 1c) What were the problems with British elections? Only 4% of men could vote! Men MPs (Members of Parliament) did not usually had to own land to be able to get paid to do their job so only rich vote. -

Events, Exhibitions & Treasures from the Collection

July —September, 2019 Quarterly Events, Exhibitions & Treasures from the Collection Features 4 Note from the Librarian The Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society 5 Library News Autumn 2019 Programme Highlights Quarterly 6 Member’s Research July—September, 2019 Nicola Higgins Nicola Kane 7 Exhibition Thursday 3rd October 2019 - RNCM Making the News: Delivering the future: Greater Manchester’s Transport Strategy Reading between the lines Since the industrial revolution and the world’s first passenger railway services, transport has from Peterloo to Meskel Square played a critical role in shaping Greater Manchester and the lives of people living in the conurba- tion. Over the coming decades Greater Manchester’s transport system will face huge challenges, 8 Event Listings such as how to cater for a growth in travel as the city’s population increases to around three mil- lion people. Nicola Kane’s lecture will provide an introduction to TfGM’s ambitious plans. 10 Library Treasures Professor Daniel M Davis Alex Boswell Thursday 10th October 2019 - RNCM The Beautiful Cure 12 Member’s Article Daniel M Davis’ research, using super-resolution microscopy to I remember, I remember study immune cell biology, was listed in Discover magazine as one of Alan Shelston the top 100 breakthroughs of the year. He is the author of the high- ly acclaimed book, ‘The Beautiful Cure’. This talk will present a revelato- ry new understanding of the human body and what it takes to be healthy. 14 Dining at The Portico Library Joe Fenn Image: The University of Manchester Derek Blyth Tuesday 15th October 2019 - RNCM 15 Volunteer Story Ellie Holly No Regrets - The Life and Music of Edith Piaf In a century known for its record keeping and attention to detail, Edith Piaf’s life can read like a fairy tale. -

The Challenge of Cholera: Proceedings of the Manchester Special Board of Health 1831-1833

The Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire Volume 145: start THE RECORD SOCIETY OF LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE FOUNDED TO TRANSCRIBE AND PUBLISH ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS RELATING TO THE TWO COUNTIES VOLUME CXLV The Society wishes to acknowledge with gratitude the support given towards publication by Lancashire County Council © The Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire Alan Kidd Terry Wyke ISBN 978 0 902593 80 0 Printed in Great Britain by 4word Ltd, Bristol THE CHALLENGE OF CHOLERA: PROCEEDINGS OF THE MANCHESTER SPECIAL BOARD OF HEALTH 1831-1833 Edited by Alan Kidd and Terry Wyke PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY 2010 FOR THE SUBSCRIPTION YEAR 2008 COUNCIL AND OFFICERS FOR THE YEAR 2008 President J.R.H. Pepler, M.A., D.A.A., c/o Cheshire Record Office, Duke Street, Chester CHI 1RL Hon. Council Secretary Dorothy J. Clayton, M.A., Ph.D., A.L.A., F.R.Hist.S., c/o John Rylands University Library of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PP Hon. Membership Secretary J.C. Sutton, M.A., F.R.I.C.S., 5 Beechwood Drive, Alsager, Cheshire, ST7 2HG Hon. Treasurer and Publications Secretary Fiona Pogson, B.A., Ph.D., c/o Department of History, Liverpool Hope University, Hope Park, Liverpool L16 9JD Hon. General Editor Peter McNiven, M.A., Ph.D., F.R.Hist.S., 105 Homegower House, St Helens Road, Swansea SA1 4DN Other Members of the Council P.H.W. Booth, M.A., F.R.Hist.S. C.B. Phillips, B.A., Ph.D. Diana E.S. Dunn, B.A., D.Ar.Studies B.W. Quintrell, M.A., Ph.D., F.R.Hist.S. -

Lancashire Historic Town Survey Programme

LANCASHIRE HISTORIC TOWN SURVEY PROGRAMME BURNLEY HISTORIC TOWN ASSESSMENT REPORT MAY 2005 Lancashire County Council and Egerton Lea Consultancy with the support of English Heritage and Burnley Borough Council Lancashire Historic Town Survey Burnley The Lancashire Historic Town Survey Programme was carried out between 2000 and 2006 by Lancashire County Council and Egerton Lea Consultancy with the support of English Heritage. This document has been prepared by Lesley Mitchell and Suzanne Hartley of the Lancashire County Archaeology Service, and is based on an original report written by Richard Newman and Caron Newman, who undertook the documentary research and field study. The illustrations were prepared and processed by Caron Newman, Lesley Mitchell, Suzanne Hartley, Nik Bruce and Peter Iles. Copyright © Lancashire County Council 2005 Contact: Lancashire County Archaeology Service Environment Directorate Lancashire County Council Guild House Cross Street Preston PR1 8RD Mapping in this volume is based upon the Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Lancashire County Council Licence No. 100023320 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Lancashire County Council would like to acknowledge the advice and assistance provided by Graham Fairclough, Jennie Stopford, Andrew Davison, Roger Thomas, Judith Nelson and Darren Ratcliffe at English Heritage, Paul Mason, John Trippier, and all the staff at Lancashire County Council, in particular Nik Bruce, Jenny Hayward, Jo Clark, Peter Iles, Peter McCrone and Lynda Sutton. Egerton Lea Consultancy Ltd wishes to thank the staff of the Lancashire Record Office, particularly Sue Goodwin, for all their assistance during the course of this study. -

Wakefield Amateur Rowing Club, 1846 – C.1876

‘Jolly Boating Weather…’ Wakefield Amateur Rowing Club, 1846 – c.1876 Nowadays rowing is typically viewed as a socially elite sport: that of grammar schools, universities and gentlemen. Whilst this is true to a point, historically rowing has cut across boundaries of class as much as any other sport. During the nineteenth century most sports, including rowing, were divided into three broad classes – working or tradesmen who made their living on the water as watermen or boatman; middle class and gentlemen amateurs; and those who made their living from the sport, who came from the working or middle class. This last group, the professional sportsmen rowers, were the equivalent of today’s superstars from football or rugby; the Clasper family or James Renforth from Newcastle had a massive following as true working class heroes who made a living from their prize money and boat-making skills. Harry Clasper (1812 to 1870) and his brothers were some of the first superstar sportsmen of their day and also the earliest professional sportsmen – in other words they were able to live from their winnings and what we would now term sponsorship. Rowing races and regattas were seen by the middle and gentry classes as a polite summer entertainment and also as the off-season equivalent of horse racing, with prizes and wagers commonly running into several hundreds of pounds. Regattas were established in London on the Thames before 1825 – the ‘Lambeth,’ ‘Blackfriars’ and ‘Tower’ regattas were held that summer with prizes being as high as £25.1 Most towns with access to a good stretch of water established Rowing Clubs, generally as an ‘out door amusement’ but increasingly during the nineteenth century for the ‘improvement of the working classes’ and ‘bringing out the bone and muscle of our English youth.. -

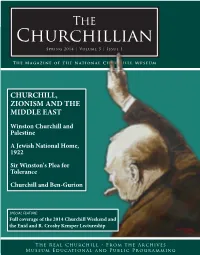

Spring 2014 | Volume 5 | Issue 1

The Churchillian Spring 2014 | Volume 5 | Issue 1 The Magazine of the National Churchill Museum CHURCHILL, ZIONISM AND THE MIDDLE EAST Winston Churchill and Palestine A Jewish National Home, 1922 Sir Winston's Plea for Tolerance Churchill and Ben-Gurion SPECIAL FEATURE: Full coverage of the 2014 Churchill Weekend and the Enid and R. Crosby Kemper Lectureship The Real Churchill • From the Archives Museum Educational and Public Programming Board of Governors of the Association of Churchill Fellows FROM THE Jean-Paul Montupet MESSAGE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Chairman & Senior Fellow St. Louis, Missouri A.V. L. Brokaw, III Warm greetings from the campus of St. Louis, Missouri Westminster College. As I write, we are Robert L. DeFer still recovering from a wonderful Churchill th Weekend. Tis weekend, marking the 68 Earle H. Harbison, Jr. St. Louis, Missouri anniversary of Churchill’s visit here and his William C. Ives Sinews of Peace address, was a special one for Chapel Hill, North Carolina several reasons. Firstly, because of the threat R. Crosby Kemper, III of bad weather which, while unpleasant, Kansas City, Missouri never realized the forecast’s dismal potential Barbara D. Lewington and because of the presence of members of St. Louis, Missouri the Churchill family, Randolph, Catherine St. Louis, Missouri and Jennie Churchill for a frst ever visit. William R. Piper Tis, in tandem with a wonderful Enid St. Louis, Missouri PHOTO BY DAK DILLON and R. Crosby Kemper Lecture delivered by Paul Reid, defed the weather and entertained a bumper crowd of St. Louis, Missouri Churchillians at both dinner, in the Museum, and at a special ‘ask the experts’ brunch. -

The Atlas of Digitised Newspapers and Metadata: Reports from Oceanic Exchanges

THE ATLAS OF DIGITISED NEWSPAPERS AND METADATA: REPORTS FROM OCEANIC EXCHANGES M. H. Beals and Emily Bell with additional contributions by Ryan Cordell, Paul Fyfe, Isabel Galina Russell, Tessa Hauswedell, Clemens Neudecker, Julianne Nyhan, Mila Oiva, Sebastian Padó, Miriam Peña Pimentel, Lara Rose, Hannu Salmi, Melissa Terras, and Lorella Viola and special thanks to Seth Cayley (Gale), Steven Claeyssens (KB), Huibert Crijns (KB), Nicola Frean (NLNZ), Julia Hickie (NLA), Jussi-Pekka Hakkarainen (NLF), Chris Houghton (Gale), Melanie Lovell-Smith (NLNZ), Minna Kaukonen (NLF), Luke McKernan (BL), Chris McPartlanda (NLA), Maaike Napolitano (KB), Tim Sherratt (University of Canberra) and Emerson Vandy (NLNZ) Document: DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.11560059 Dataset: DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.11560110 Disclaimer: This project was made possible by funding from Digging into Data, Round Four (HJ-253589). Although we have directly consulted with the various institutions discussed in this report, the final findings, conclusions and recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the discussed database providers or the contributors’ host institutions. Executive Summary Between 2017 and 2019, Oceanic Exchanges (http://www.oceanicexchanges.org), funded through the Transatlantic Partnership for Social Sciences and Humanities 2016 Digging into Data Challenge (https://diggingintodata.org), brought together leading efforts in computational periodicals research from six countries—Finland, Germany, Mexico, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States—to examine patterns of information flow across national and linguistic boundaries. Over the past thirty years, national libraries, universities and commercial publishers around the world have made available hundreds of millions of pages of historical newspapers through mass digitisation and currently release over one million new pages per month worldwide. -

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman, QC. Part I. BERNARD QUARITCH LTD MMXX BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] / [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 Front cover: from item 106 (Gillray) Rear cover: from item 281 (Peterloo Massacre) Opposite: from item 276 (‘Martial’) List 2020/1 Introduction My father qualified in medicine at Durham University in 1926 and practised in Gateshead on Tyne for the next 43 years – excluding 6 years absence on war service from 1939 to 1945. From his student days he had been an avid book collector. He formed relationships with antiquarian booksellers throughout the north of England. His interests were eclectic but focused on English literature of the 17th and 18th centuries. Several of my father’s books have survived in the present collection. During childhood I paid little attention to his books but in later years I too became a collector. During the war I was evacuated to the Lake District and my school in Keswick incorporated Greta Hall, where Coleridge lived with Robert Southey and his family. So from an early age the Lake Poets were a significant part of my life and a focus of my book collecting. -

THE JOURNAL of ROMAN STUDIES All Rights Reserved

THE JOURNAL OF ROMAN STUDIES All rights reserved. THE JOURNAL OF ROMAN STUDIES VOLUME XI PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY FOR THE PRO- MOTION OF ROMAN STUDIES AT THE OFFICE OF THE SOCIETY, 19 BLOOMSBURY SQUARE, W.C.I. LONDON 1921 The printing of this -part was completed on October 20th, 1923. CONTENTS PAGE G. MACDONALD. The Building of the Antonine Wall : a Fresh Study of the Inscriptions I ENA MAKIN. The Triumphal Route, with particular reference to the Flavian Triumph 25 R. G. COLLINGWOOD. Hadrian's Wall: a History of the Problem ... ... 37 R. E. M. WHEELER. A Roman Fortified House near Cardiff 67 W. S. FERGUSON. The Lex Calpurnia of 149 B.C 86 PAUL COURTEAULT. An Inscription recently found at Bordeaux iof GRACE H. MACURDY. The word ' Sorex' in C.I.L. i2, 1988,1989 108 T. ASHBY and R. A. L. FELL. The Via Flaminia 125 J. S. REID. Tacitus as a Historian 191 M. V. TAYLOR and R G. COLLINCWOOD. Roman Britain in 1921 and 1922 200 J. WHATMOUGH. Inscribed Fragments of Stagshorn from North Italy ... 245 H. MATTINGLY. The Mints of the Empire: Vespasian to Diocletian ... 254 M. L. W. LAISTNER. The Obelisks of Augustus at Rome ... 265 M. L. W. LAISTNER. Dediticii: the Source of Isidore (Etym. 9, 4, 49-50) 267 Notices of Recent Publications (for list see next page) m-123, 269-285 M. CARY. Note on ' Sanguineae Virgae ' (J.R.S. vo. ix, p. 119) 285 Errata 287 Proceedings of the Society, 1921 288 Report of the Council and Statement of Accounts for the year 1920 289 Index .. -

Benjamin F. Fisher the Red Badge of Courage Under British Spotlights Again

Benjamin F. Fisher The Red Badge of Courage under British Spotlights Again hese pages provide information that augments my previous publications concerning discoveries about contemporaneous British opinions of The Red Badge of CourageT. I am confident that what appears in this and my earlier article [WLA Special Issue 1999] on the subject offers a mere fraction of such materials, given, for example, the large numbers of daily newspapers published in London alone during the 1890s. Files of many British periodicals and newspapers from the Crane era are no longer extant, principally because of bomb damage to repositories of such materials during wartime. The commentary garnered below, how- ever, amplifies our knowledge relating to Crane’s perennially compel- ling novel, and thus, I trust, it should not go unrecorded. If one wonders why, after a century, such a look backward might be of value to those interested in Crane, I cite a letter of Ford Maddox Ford to Paul Palmer, 11 December 1935, in which he states that Crane, along with Henry James, W.H. Hudson, and Joseph Conrad all “exercised an enormous influence on English—and later, American writing. .” Ford’s thoughts concerning Crane’s importance were essentially repeated in a later letter, to the editor of the Saturday Review of Literature.1 Despite many unreliabilities in what Ford put into print on any subject, he thor- oughly divined the Anglo-American literary climate from the 1890s to the 1930s. His ideas are representative of views of Crane in British eyes during that era and, for that matter, views that have maintained cur- rency to the present time. -

The Manchester Observer: Biography of a Radical Newspaper

Article The Manchester Observer: biography of a radical newspaper Poole, Robert Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/28037/ Poole, Robert ORCID: 0000-0001-9613-6401 (2019) The Manchester Observer: biography of a radical newspaper. Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 95 (1). pp. 31-123. ISSN 2054-9318 It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. http://dx.doi.org/10.7227/BJRL.95.1.3 For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk i i i i The Manchester Observer: Biography of a Radical Newspaper ROBERT POOLE, UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL LANCASHIRE Abstract The newly digitised Manchester Observer (1818–22) was England’s leading rad- ical newspaper at the time of the Peterloo meeting of August 1819, in which it played a central role. For a time it enjoyed the highest circulation of any provincial newspaper, holding a position comparable to that of the Chartist Northern Star twenty years later and pioneering dual publication in Manchester and London. -

The Queen Caroline Affair: Politics As Art in the Reign of George IV Author(S): Thomas W

The Queen Caroline Affair: Politics as Art in the Reign of George IV Author(s): Thomas W. Laqueur Source: The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 54, No. 3 (Sep., 1982), pp. 417-466 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1906228 Accessed: 06-03-2020 19:28 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Modern History This content downloaded from 130.132.173.181 on Fri, 06 Mar 2020 19:28:02 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The Queen Caroline Affair: Politics as Art in the Reign of George IV* Thomas W. Laqueur University of California, Berkeley Seldom has there been so much commotion over what appears to be so little as in the Queen Caroline affair, the agitation on behalf of a not- very-virtuous queen whose still less virtuous husband, George IV, want- ed desperately to divorce her. During much of 1820 the "queen's busi- ness" captivated the nation. "It was the only question I have ever known," wrote the radical critic William Hazlitt, "that excited a thor- ough popular feeling.