Noun Countability; Count Nouns and Non-Count Nouns, What Are the Syntactic Differences Between Them?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding English Non-Count Nouns and Indefinite Articles

Understanding English non-count nouns and indefinite articles Takehiro Tsuchida Digital Hollywood University December 20, 2010 Introduction English nouns are said to be categorised into several groups according to certain criteria. Among such classifications is the division of count nouns and non-count nouns. While count nouns have such features as plural forms and ability to take the indefinite article a/an, non-count nouns are generally considered to be simply the opposite. The actual usage of nouns is, however, not so straightforward. Nouns which are usually regarded as uncountable sometimes take the indefinite article and it seems fairly difficult for even native speakers of English to expound the mechanism working in such cases. In particular, it seems to be fairly peculiar that the noun phrase (NP) whose head is the abstract „non-count‟ noun knowledge often takes the indefinite article a/an and makes such phrase as a good knowledge of Greek. The aim of this paper is to find out reasonable answers to the question of why these phrases occur in English grammar and thereby to help native speakers/teachers of English and non-native teachers alike to better instruct their students in 1 the complexity and profundity of English count/non-count dichotomy and actual usage of indefinite articles. This report will first examine the essential qualities of non-count nouns and indefinite articles by reviewing linguistic literature. Then, I shall conduct some research using the British National Corpus (BNC), focusing on statistical and semantic analyses, before finally certain conclusions based on both theoretical and actual observations are drawn. -

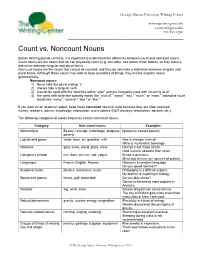

Count Vs Noncount Nouns

George Mason University Writing Center writingcenter.gmu.edu The [email protected] Writing Center 703.993.1200 Count vs. Noncount Nouns Before forming plurals correctly, it is important to understand the difference between count and noncount nouns. Count nouns are the nouns that we can physically count (e.g. one table, two tables, three tables), so they make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Noncount nouns are the nouns that cannot be counted, and they do not make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Although these nouns may refer to large quantities of things, they act like singular nouns grammatically. Noncount nouns: 1) Never take the plural ending “s” 2) Always take a singular verb 3) Cannot be used with the indefinite article “a/an” and are frequently used with no article at all 4) Are used with collective quantity words like “a lot of,” “some,” “any,” “much,” or “more,” instead of count words like “many,” “several,” “two,” or “few.” If you work on an academic paper, keep these noncount nouns in mind because they are often misused: money, research, advice, knowledge, information, and evidence (NOT moneys, researches, advices, etc.). The following categories of words frequently contain noncount nouns: Category Non-count nouns Examples Abstractions Beauty, revenge, knowledge, progress, Ignorance causes poverty. poverty Liquids and gases water, beer, air, gasoline, milk Gas is cheaper than oil. Wine is my favorite beverage. Materials gold, silver, wood, glass, sand He had a will made of iron. Gold is more valuable than silver. Categories of food rice, flour, cheese, salt, yogurt Bread is delicious. -

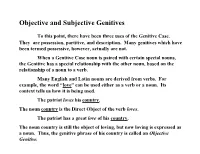

Objective and Subjective Genitives

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium. -

Finnish Partitive Case As a Determiner Suffix

Finnish partitive case as a determiner suffix Problem: Finnish partitive case shows up on subject and object nouns, alternating with nominative and accusative respectively, where the interpretation involves indefiniteness or negation (Karlsson 1999). On these grounds some researchers have proposed that partitive is a structural case in Finnish (Vainikka 1993, Kiparsky 2001). A problematic consequence of this is that Finnish is assumed to have a structural case not found in other languages, losing the universal inventory of structural cases. I will propose an alternative, namely that partitive be analysed instead as a member of the Finnish determiner class. Data: There are three contexts in which the Finnish subject is in the partitive (alternating with the nominative in complementary contexts): (i) indefinite divisible non-count nouns (1), (ii) indefinite plural count nouns (2), (iii) where the existence of the argument is completely negated (3). The data are drawn from Karlsson (1999:82-5). (1) Divisible non-count nouns a. Partitive mass noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative mass noun = def Purki-ssa on leipä-ä. Leipä on purki-ssa. tin-INESS is bread-PART Bread is tin-INESS ‘There is some bread in the tin.’ ‘The bread is in the tin.’ (2) Plural count nouns a. Partitive count noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative count noun = def Kadu-lla on auto-j-a. Auto-t ovat kadulla. Street-ADESS is.3SG car-PL-PART Car-PL are.3PL street-ADESS ‘There are cars in the street.’ ‘The cars are in the street.’ (3) Negation a. Partitive, negation of existence b. c.f. -

Syntactic Variation in English Quantified Noun Phrases with All, Whole, Both and Half

Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half Acta Wexionensia Nr 38/2004 Humaniora Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half Maria Estling Vannestål Växjö University Press Abstract Estling Vannestål, Maria, 2004. Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half, Acta Wexionensia nr 38/2004. ISSN: 1404-4307, ISBN: 91-7636-406-2. Written in English. The overall aim of the present study is to investigate syntactic variation in certain Present-day English noun phrase types including the quantifiers all, whole, both and half (e.g. a half hour vs. half an hour). More specific research questions concerns the overall frequency distribution of the variants, how they are distrib- uted across regions and media and what linguistic factors influence the choice of variant. The study is based on corpus material comprising three newspapers from 1995 (The Independent, The New York Times and The Sydney Morning Herald) and two spoken corpora (the dialogue component of the BNC and the Longman Spoken American Corpus). The book presents a number of previously not discussed issues with respect to all, whole, both and half. The study of distribution shows that one form often predominated greatly over the other(s) and that there were several cases of re- gional variation. A number of linguistic factors further seem to be involved for each of the variables analysed, such as the syntactic function of the noun phrase and the presence of certain elements in the NP or its near co-text. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability1

Eun-Joo Kwak 55 Journal of Universal Language 15-2 September 2014, 55-76 Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability1 2 Eun-Joo Kwak Sejong University, Korea Abstract Countability and plurality (or singularity) are basically marked in syntax or morphology, and languages adopt different strategies in the mass-count distinction and number marking: plural marking, unmarked number marking, singularization, and different uses of classifiers. Diverse patterns of grammatical strategies are observed with cross-linguistic data in this study. Based on this, it is concluded that although countability is not solely determined by the semantic properties of nouns, it is much more affected by semantics than it appears. Moreover, semantic features of nouns are useful to account for apparent idiosyncratic behaviors of nouns and sentences. Keywords: countability, plurality, countability shift, individuation, animacy, classifier * This work is supported by the Sejong University Research Grant of 2013. Eun-Joo Kwak Department of English Language and Literature, Sejong University, Seoul, Korea Phone: +82-2-3408-3633; Email: [email protected] Received August 14, 2014; Revised September 3, 2014; Accepted September 10, 2014. 56 Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability 1. Introduction The state of affairs in the real world may be delivered in a different way depending on the grammatical properties of languages. Nominal countability makes part of grammatical differences cross-linguistically, marked in various ways: plural (or singular) morphemes for nouns or verbs, distinct uses of determiners, and the occurrences of classifiers. Apparently, countability and plurality are mainly marked in syntax and morphology, so they may be understood as having less connection to the semantic features of nouns. -

A Corpus Study of Partitive Expression – Uncountable Noun Collocations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayerau Osijeku Filozofskifakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Pedagogije Anja Kolobarić A Corpus Study of Partitive Expression – Uncountable Noun Collocations Završni rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc Gabrijela Buljan Osijek, 2014. Summary This research paper explores partitive expressions not only as devices that impose countable readings in uncountable nouns, but also as a means of directing the interpretive focus on different aspects of the uncountable entities denoted by nouns. This exploration was made possible through a close examination of specific grammar books, but also through a small-scale corpus study we have conducted. We first explain the theory behind uncountable nouns and partitive expressions, and then present the results of our corpus study, demonstrating thereby the creative nature of the English language. We also propose some cautious generalizations concerning the distribution of partitive expressions within the analyzed semantic domains. Key words: noncount noun, concrete noun, partitive expression, corpus data, data analysis 2 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 4 2. Theoretical Framework ........................................................................................... 5 2.1 Distinction between Count and Noncount -

The Semantics of Structural Case in Finnish

Absolutely a Matter of Degree: The Semantics of Structural Case in Finnish Paul Kiparsky CLS, April 2005 1. Functional categories (1) What are the functional categories of a language? A proposal. a. Syntax: functional categories are projected by functional heads. b. Morphology: functional categories are assigned by affixes or inherently marked on lexical items. c. Null elements may mark default values in paradigmatic system of functional categories. d. Otherwise functional categories are not specified. (2) a. Diachronic evidence: syntactic projections of functional categories emerge hand in hand with lexical heads (e.g. Kiparsky 1996, 1997 on English, Condoravdi and Kiparsky 2002, 2004 on Greek.) b. Empirical arguments from morphology (e.g. Kiparsky 2004). (3) Minimalist analysis of Accusative vs. Partitive case in Finnish (Borer 1998, 2005, Megerdoo- mian 2000, van Hout 2000, Ritter and Rosen 2000, Csirmaz 2002, Kratzer 2002, Svenonius 2002, Thomas 2003). a. Accusative is checked in AspP, a functional projection which induces telicity. b. Partitive is checked in a lower projection. • (1) rules out AspP for Finnish. (4) Position defended here (Kiparsky 1998): a. Accusative case is assigned to complements of BOUNDED (non-gradable) verbal pred- icates. b. Otherwise complements are assigned Partitive case. (5) Partitive case in Finnish: • a structural case (Vainikka 1993, Kiparsky 2001), • the default case of complements (Vainikka 1993, Anttila & Fong 2001), • syntactically alternates with Nominative, Genitive, and Accusative case. 1 • Following traditional grammar, we’ll treat Accusative as an abstract case that includes in addition to Accusative itself, the Accusative-like uses of Nominative and Genitive (for a different proposal, see Kiparsky 2001). -

3 Types of Anaphors

3 Types of anaphors Moving from the definition and characteristics of anaphors to the types of ana- phors, this chapter will detail the nomenclature of anaphor types established for this book. In general, anaphors can be categorised according to: their form; the type of relationship to their antecedent; the form of their antecedents; the position of anaphors and antecedents, i.e. intrasentential or intersentential; and other features (cf. Mitkov 2002: 8-17). The procedure adopted here is to catego- rise anaphors according to their form. It should be stressed that the types dis- tinguished in this book are not universal categories, so the proposed classifica- tion is not the only possible solution. For instance, personal, possessive and re- flexive pronouns can be seen as three types or as one type. With the latter, the three pronoun classes are subsumed under the term “central pronouns”, as it is adopted here. Linguistic classifications of anaphors can be found in two established gram- mar books, namely in Quirk et al.’s A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language (2012: 865) and in The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (Stirling & Huddleston 2010: 1449-1564). Quirk et al. include a chapter of pro- forms and here distinguish between coreference and substitution. However, they do not take anaphors as their starting point of categorisation. Additionally, Stirling & Huddleston do not consider anaphors on their own but together with deixis. As a result, anaphoric noun phrases with a definite article, for example, are not included in both categorisations. Furthermore, Schubert (2012: 31-55) presents a text-linguistic view, of which anaphors are part, but his classification is similarly unsuitable because it does not focus on the anaphoric items specifi- cally. -

English 4 Using Clear and Coherent Sentences Employing Grammatical Structures Second Quarter - Week 2

Department of Education English 4 Using Clear and Coherent Sentences employing Grammatical Structures Second Quarter - Week 2 Adelinda D. Dollesin Writer Hilario G. Canasa Dr. Ma. Myra E. Namit Validators Ivy M. Romano Ada T. Tagle Cecilia Theresa C. Claudel Dr. Ma. Theresa C. Dela Rosa Dr. Ma. Carmen D. Solayao Dr. Shella C. Navarro Quality Assurance Team Schools Division Office – Muntinlupa City Student Center for Life Skills Bldg., Centennial Ave., Brgy. Tunasan, Muntinlupa City (02) 8805-9935 / (02) 8805-9940 1 This module was designed to help you master the use of clear and coherent sentences employing appropriate grammatical structures (Kinds of Nouns: Count and Mass, Possessive and Collective Nouns) After going through this module, you are expected to: 1. Define and identify the kinds of nouns: mass and count nouns, possessive and collective nouns; and 2. Classify and use kinds of nouns (mass and count nouns, possessive and collective nouns) in simple sentence. A. Directions: Encircle the letter of the correct answer. 1. Linda will buy juice and chicken from the store. Which of the following words is a mass noun? A. chicken C. Linda B. juice D. store 2. Nena will use the long spoon for halo-halo. Which of the following is a count noun? A. Long C. use B. spoon D. will 3. They put sugar in the jar. What is the count noun in the sentence? A. jar C. sugar B. put D. they 4. Hera added rice in a bowl. Which is the mass noun in the sentence? A. bowl C. Hera B. -

A Case Study in Language Change

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-17-2013 Glottopoeia: A Case Study in Language Change Ian Hollenbaugh Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Other English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hollenbaugh, Ian, "Glottopoeia: A Case Study in Language Change" (2013). Honors Theses. 2243. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/2243 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Elementary Ghau Aethauic Grammar By Ian Hollenbaugh 1 i. Foreword This is an essential grammar for any serious student of Ghau Aethau. Mr. Hollenbaugh has done an excellent job in cataloguing and explaining the many grammatical features of one of the most complex language systems ever spoken. Now published for the first time with an introduction by my former colleague and premier Ghau Aethauic scholar, Philip Logos, who has worked closely with young Hollenbaugh as both mentor and editor, this is sure to be the definitive grammar for students and teachers alike in the field of New Classics for many years to come. John Townsend, Ph.D Professor Emeritus University of Nunavut 2 ii. Author’s Preface This grammar, though as yet incomplete, serves as my confession to what J.R.R. Tolkien once called “a secret vice.” History has proven Professor Tolkien right in thinking that this is not a bizarre or freak occurrence, undergone by only the very whimsical, but rather a common “hobby,” one which many partake in, and have partaken in since at least the time of Hildegard of Bingen in the twelfth century C.E.