Typology of Partitives Received October 28, 2019; Accepted November 17, 2020; Published Online February 18, 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estonian Transitive Verb Classes, Object Case, and Progressive1 Anne Tamm Research Institute for Linguistics, Budapest

Estonian transitive verb classes, object case, and progressive1 Anne Tamm Research Institute for Linguistics, Budapest 1. Introduction The aim of this article is to show the relation between aspect and object case in Estonian and to establish a verb classification that is predictive of object case behavior. Estonian sources disagree on the nature of the grounds for an aspectual verb classification and, therefore, on the exact verbal classes. However, the morphological genitive and nominative case marking as opposed to the morphological partitive case marking of Estonian objects is uniformly seen as an important indicator for an aspectual verb class membership. In addition, object case alternation reflects the aspectual oppositions of perfectivity and imperfectivity that cannot be accounted for by verbal lexical aspect only. This article spells out these aspectual phenomena, relating them to a verb classification. The verb classes are distinguished from each other according to the nature of the situations or events they typically describe. The verb classification is established on the basis of tests that involve only the partitive object case. These tests use the phenomena related to progressive in Estonian. 2. A note on terminology Several accounts of aspectuality view a sentence’s aspectual properties as being determined by more components in a sentence than just the verb alone. More specifically, two temporal factors of situations or aspectuality are distinguished: on the one hand, boundedness, viewpoint, or perfectivity and, on the other hand, situation, event structure or telicity (Smith 1990, Verkuyl 1989, Depraetere 1995). Authors such as Verkuyl (1989) distinguish syntactically two distinct levels of aspectuality. The VP aspectual level, that is, the aspectual phenomena at the level of the verb and its complements, is referred to as telicity, VP- terminativity, or event structure. -

Acoustic Evidence for Right-Edge Prominence in Nafsana)

...................................ARTICLE Acoustic evidence for right-edge prominence in Nafsana) Rosey Billington,b) Janet Fletcher,c) Nick Thieberger,d) and Ben Volchok ARC Centre of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language, School of Languages and Linguistics, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria 3052, Australia ABSTRACT: Oceanic languages are often described as preferring primary stress on penultimate syllables, but detailed surveys show that many different types of prominence patterns have been reported across and within Oceanic language families. In some cases, these interact with segmental and phonotactic factors, such as syllable weight. The range of Oceanic prominence patterns is exemplified across Vanuatu, a linguistically diverse archipelago with over 130 languages. However, both impressionistic and instrumentally-based descriptions of prosodic patterns and their correlates are limited for languages of this region. This paper investigates prominence in Nafsan, an Oceanic language of Vanuatu for which previous observations of prominence differ. Acoustic and durational results for disyl- labic and trisyllabic Nafsan words show a clear pattern of higher fundamental frequency values in final syllables, regardless of vowel length, pointing towards a preference for prominence at the right edge of words. Short vowels also show centralisation in penultimate syllables, providing supporting evidence for right-edge prominence and informing the understanding of vowel deletion processes in Nafsan. VC 2020 Acoustical Society of America. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0000995 (Received 3 May 2019; revised 15 September 2019; accepted 16 October 2019; published online 30 April 2020) [Editor: Benjamin V. Tucker] Pages: 2829–2844 I. INTRODUCTION empirically. The present study is part of a wider project using instrumental phonetic approaches to investigate vari- This paper investigates prominence in Nafsan (South ous aspects of Nafsan phonology. -

Prior Linguistic Knowledge Matters : the Use of the Partitive Case In

B 111 OULU 2013 B 111 UNIVERSITY OF OULU P.O.B. 7500 FI-90014 UNIVERSITY OF OULU FINLAND ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA SERIES EDITORS HUMANIORAB Marianne Spoelman ASCIENTIAE RERUM NATURALIUM Marianne Spoelman Senior Assistant Jorma Arhippainen PRIOR LINGUISTIC BHUMANIORA KNOWLEDGE MATTERS University Lecturer Santeri Palviainen CTECHNICA THE USE OF THE PARTITIVE CASE IN FINNISH Docent Hannu Heusala LEARNER LANGUAGE DMEDICA Professor Olli Vuolteenaho ESCIENTIAE RERUM SOCIALIUM University Lecturer Hannu Heikkinen FSCRIPTA ACADEMICA Director Sinikka Eskelinen GOECONOMICA Professor Jari Juga EDITOR IN CHIEF Professor Olli Vuolteenaho PUBLICATIONS EDITOR Publications Editor Kirsti Nurkkala UNIVERSITY OF OULU GRADUATE SCHOOL; UNIVERSITY OF OULU, FACULTY OF HUMANITIES, FINNISH LANGUAGE ISBN 978-952-62-0113-9 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-0114-6 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3205 (Print) ISSN 1796-2218 (Online) ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS B Humaniora 111 MARIANNE SPOELMAN PRIOR LINGUISTIC KNOWLEDGE MATTERS The use of the partitive case in Finnish learner language Academic dissertation to be presented with the assent of the Doctoral Training Committee of Human Sciences of the University of Oulu for public defence in Keckmaninsali (Auditorium HU106), Linnanmaa, on 24 May 2013, at 12 noon UNIVERSITY OF OULU, OULU 2013 Copyright © 2013 Acta Univ. Oul. B 111, 2013 Supervised by Docent Jarmo H. Jantunen Professor Helena Sulkala Reviewed by Professor Tuomas Huumo Associate Professor Scott Jarvis Opponent Associate Professor Scott Jarvis ISBN 978-952-62-0113-9 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-0114-6 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3205 (Printed) ISSN 1796-2218 (Online) Cover Design Raimo Ahonen JUVENES PRINT TAMPERE 2013 Spoelman, Marianne, Prior linguistic knowledge matters: The use of the partitive case in Finnish learner language University of Oulu Graduate School; University of Oulu, Faculty of Humanities, Finnish Language, P.O. -

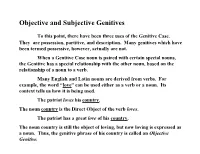

Objective and Subjective Genitives

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium. -

Finnish Partitive Case As a Determiner Suffix

Finnish partitive case as a determiner suffix Problem: Finnish partitive case shows up on subject and object nouns, alternating with nominative and accusative respectively, where the interpretation involves indefiniteness or negation (Karlsson 1999). On these grounds some researchers have proposed that partitive is a structural case in Finnish (Vainikka 1993, Kiparsky 2001). A problematic consequence of this is that Finnish is assumed to have a structural case not found in other languages, losing the universal inventory of structural cases. I will propose an alternative, namely that partitive be analysed instead as a member of the Finnish determiner class. Data: There are three contexts in which the Finnish subject is in the partitive (alternating with the nominative in complementary contexts): (i) indefinite divisible non-count nouns (1), (ii) indefinite plural count nouns (2), (iii) where the existence of the argument is completely negated (3). The data are drawn from Karlsson (1999:82-5). (1) Divisible non-count nouns a. Partitive mass noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative mass noun = def Purki-ssa on leipä-ä. Leipä on purki-ssa. tin-INESS is bread-PART Bread is tin-INESS ‘There is some bread in the tin.’ ‘The bread is in the tin.’ (2) Plural count nouns a. Partitive count noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative count noun = def Kadu-lla on auto-j-a. Auto-t ovat kadulla. Street-ADESS is.3SG car-PL-PART Car-PL are.3PL street-ADESS ‘There are cars in the street.’ ‘The cars are in the street.’ (3) Negation a. Partitive, negation of existence b. c.f. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

Reflexives Markers in Oceanic Languages

DGfS-CNRS Summer School: Linguistic Typology (3) Koenig/Moyse-Faurie Reflexives markers in Oceanic Languages Ekkehard König (FU Berlin) & Claire Moyse-Faurie (Lacito-CNRS) 1. Previous views 1.1. A lack of reflexive markers ? “[Oceanic languages] have morphological markers used to encode reciprocal and certain other situations, but not reflexive situations” (Lichtenberk, 2000:31). “Assuming that reflexivity is inherently related to transitivity, we understand why we do not find morphosyntactic reflexivisation in Samoan: Samoan does not have syntactically transitive clauses” (Mosel, 1991: ‘Where have all the Samoan reflexives gone?’) “There is no mark of reflexive, either in the form of a reflexive pronoun or of a reflexive marker on the verb – one simply says I saw me” (Dixon, 1988:9). Out of context, there are indeed many cases of ambiguity with 3rd persons, due to the frequent absence of obligatory grammaticalized constructions to express reflexivity: XÂRÂGURÈ (South of the Mainland, New Caledonia) (1) nyî xati nyî 3SG scold 3SG ‘He is scolding him/himself.’ NUMÈÈ (Far South of the Mainland, New Caledonia) (2) treâ trooke nê kwè nê ART.PL dog 3PL bite 3PL ‘The dogs are biting them/each other.’ MWOTLAP (North Central Vanuatu) (3) Kēy mu-wuh mat kēy 3PL PERF-hit die 3PL ‘They killed each other/themselves.’ (François, 2001:372) TOQABAQITA (South East Solomon) (4) Keero’a keko thathami keero’a 3DU 3DU like 3DU ‘They liked them/each other/themselves.’ (Lichtenberk, 1991:172) 1.2. Confusion between middle markers and reflexive markers “In East Futunan, the reflexive meaning is either lexicalised (i.e. expressed by lexically reflexive verbs) or by transitive verbs, the two arguments of which refer to the same entity. -

A Corpus Study of Partitive Expression – Uncountable Noun Collocations

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek Sveučilište J. J. Strossmayerau Osijeku Filozofskifakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Pedagogije Anja Kolobarić A Corpus Study of Partitive Expression – Uncountable Noun Collocations Završni rad Mentor: izv. prof. dr. sc Gabrijela Buljan Osijek, 2014. Summary This research paper explores partitive expressions not only as devices that impose countable readings in uncountable nouns, but also as a means of directing the interpretive focus on different aspects of the uncountable entities denoted by nouns. This exploration was made possible through a close examination of specific grammar books, but also through a small-scale corpus study we have conducted. We first explain the theory behind uncountable nouns and partitive expressions, and then present the results of our corpus study, demonstrating thereby the creative nature of the English language. We also propose some cautious generalizations concerning the distribution of partitive expressions within the analyzed semantic domains. Key words: noncount noun, concrete noun, partitive expression, corpus data, data analysis 2 Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 4 2. Theoretical Framework ........................................................................................... 5 2.1 Distinction between Count and Noncount -

The Semantics of Structural Case in Finnish

Absolutely a Matter of Degree: The Semantics of Structural Case in Finnish Paul Kiparsky CLS, April 2005 1. Functional categories (1) What are the functional categories of a language? A proposal. a. Syntax: functional categories are projected by functional heads. b. Morphology: functional categories are assigned by affixes or inherently marked on lexical items. c. Null elements may mark default values in paradigmatic system of functional categories. d. Otherwise functional categories are not specified. (2) a. Diachronic evidence: syntactic projections of functional categories emerge hand in hand with lexical heads (e.g. Kiparsky 1996, 1997 on English, Condoravdi and Kiparsky 2002, 2004 on Greek.) b. Empirical arguments from morphology (e.g. Kiparsky 2004). (3) Minimalist analysis of Accusative vs. Partitive case in Finnish (Borer 1998, 2005, Megerdoo- mian 2000, van Hout 2000, Ritter and Rosen 2000, Csirmaz 2002, Kratzer 2002, Svenonius 2002, Thomas 2003). a. Accusative is checked in AspP, a functional projection which induces telicity. b. Partitive is checked in a lower projection. • (1) rules out AspP for Finnish. (4) Position defended here (Kiparsky 1998): a. Accusative case is assigned to complements of BOUNDED (non-gradable) verbal pred- icates. b. Otherwise complements are assigned Partitive case. (5) Partitive case in Finnish: • a structural case (Vainikka 1993, Kiparsky 2001), • the default case of complements (Vainikka 1993, Anttila & Fong 2001), • syntactically alternates with Nominative, Genitive, and Accusative case. 1 • Following traditional grammar, we’ll treat Accusative as an abstract case that includes in addition to Accusative itself, the Accusative-like uses of Nominative and Genitive (for a different proposal, see Kiparsky 2001). -

The Paamese Language of Vanuatu

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series B - No. 87 THE PAAMESE LANGUAGE OF VANUATU by Terry Crowley Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Crowley, T. The Paamese language of Vanuatu. B-87, xii + 280 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1982. DOI:10.15144/PL-B87.cover ©1982 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A - Occasional Papers SERIES B - Monographs SERIES C - Books SERIES D - Special Publications EDITOR: S.A. Wurm ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock, C.L. Voorhoeve, D.T. Tryon, T.E. Dutton EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B.W. Bender John Lynch University of Hawaii University of Papua New Guinea David Bradley K.A. McElhanon La Trobe University University of Texas A. Capell H.P. McKaughan University of Sydney University of Hawaii Michael G. Clyne P. MUhlhliusler Monash University Linacre College, Oxford S.H. Elbert G.N. O'Grady University of Hawaii University of Victoria, B.C. K.J. Franklin A.K. Pawley Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Auckland W.W. Glover K.L. Pike University of Michigan; Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics G.W. Grace E.C. Polome University of Hawaii University of Texas M.A.K. Halliday Gillian Sankoff University of Sydney University of Pennsylvania E. Haugen W.A.L. Stokhof National Center for Harvard University Language Development, Jakarta; A. Healey University of Leiden Summer Institute of Linguistics E. -

Berkeley Linguistics Society

PROCEEDINGS OF THE FORTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING OF THE BERKELEY LINGUISTICS SOCIETY February 7-8, 2015 General Session Special Session Fieldwork Methodology Editors Anna E. Jurgensen Hannah Sande Spencer Lamoureux Kenny Baclawski Alison Zerbe Berkeley Linguistics Society Berkeley, CA, USA Berkeley Linguistics Society University of California, Berkeley Department of Linguistics 1203 Dwinelle Hall Berkeley, CA 94720-2650 USA All papers copyright c 2015 by the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN: 0363-2946 LCCN: 76-640143 Contents Acknowledgments . v Foreword . vii The No Blur Principle Effects as an Emergent Property of Language Systems Farrell Ackerman, Robert Malouf . 1 Intensification and sociolinguistic variation: a corpus study Andrea Beltrama . 15 Tagalog Sluicing Revisited Lena Borise . 31 Phonological Opacity in Pendau: a Local Constraint Conjunction Analysis Yan Chen . 49 Proximal Demonstratives in Predicate NPs Ryan B . Doran, Gregory Ward . 61 Syntax of generic null objects revisited Vera Dvořák . 71 Non-canonical Noun Incorporation in Bzhedug Adyghe Ksenia Ershova . 99 Perceptual distribution of merging phonemes Valerie Freeman . 121 Second Position and “Floating” Clitics in Wakhi Zuzanna Fuchs . 133 Some causative alternations in K’iche’, and a unified syntactic derivation John Gluckman . 155 The ‘Whole’ Story of Partitive Quantification Kristen A . Greer . 175 A Field Method to Describe Spontaneous Motion Events in Japanese Miyuki Ishibashi . 197 i On the Derivation of Relative Clauses in Teotitlán del Valle Zapotec Nick Kalivoda, Erik Zyman . 219 Gradability and Mimetic Verbs in Japanese: A Frame-Semantic Account Naoki Kiyama, Kimi Akita . 245 Exhaustivity, Predication and the Semantics of Movement Peter Klecha, Martina Martinović . 267 Reevaluating the Diphthong Mergers in Japono-Ryukyuan Tyler Lau . -

Estonian Transitive Verbs and Object Case

ESTONIAN TRANSITIVE VERBS AND OBJECT CASE Anne Tamm University of Florence Proceedings of the LFG06 Conference Universität Konstanz Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King (Editors) 2006 CSLI Publications http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/ Abstract This article discusses the nature of Estonian aspect and case, proposing an analysis of Estonian verbal aspect, aspectual case, and clausal aspect. The focus is on the interaction of transitive telic verbs ( write, win ) and aspectual case at the level of the functional structure. The main discussion concerns the relationships between aspect and the object case alternation. The data set comprises Estonian transitive verbs with variable and invariant aspect and shows that clausal aspect ultimately depends on the object case. The objects of Estonian transitive verbs in active affirmative indicative clauses are marked with the partitive or the total case; the latter is also known as the accusative and the morphological genitive or nominative. The article presents a unification-based approach in LFG: the aspectual features of verbs and case are unified in the functional structure. The lexical entries for transitive verbs are provided with valued or unvalued aspectual features in the lexicon. If the verb fully determines sentential aspect, then the aspectual feature is valued in the functional specifications of the lexical entry of the verb; this is realized in the form of defining equations. If the aspect of the verb is variable, the entry’s functional specifications have the form of existential constraints. As sentential aspect is fully determined by the total case, the functional specifications of the lexical entry of the total case are in the form of defining equations.