HISTORIC STRUCTURE REPORT SHIRLEY-EUSTIS HOUSE Roxbury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1970 The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740 Ronald P. Dufour College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Dufour, Ronald P., "The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740" (1970). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624699. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ssac-2z49 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEE DEVELOPMENT OF POLITICAL THEORY IN COLONIAL MASSACHUSETTS 1688 - 17^0 A Th.esis Presented to 5he Faculty of the Department of History 5he College of William and Mary in Virginia In I&rtial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Ronald P. Dufour 1970 ProQ uest Number: 10625131 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10625131 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. -

Myth and Memory: the Legacy of the John Hancock House

MYTH AND MEMORY: THE LEGACY OF THE JOHN HANCOCK HOUSE by Rebecca J. Bertrand A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in American Material Culture Spring 2010 Copyright 2010 Rebecca J. Bertrand All Rights Reserved MYTH AND MEMORY: THE LEGACY OF THE JOHN HANCOCK HOUSE by Rebecca J. Bertrand Approved: __________________________________________________________ Brock Jobe, M.A. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: __________________________________________________________ J. Ritchie Garrison, Ph.D. Director of the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Debra Hess Norris, M.S. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Every Massachusetts schoolchild walks Boston’s Freedom Trail and learns the story of the Hancock house. Its demolition served as a rallying cry for early preservationists and students of historic preservation study its importance. Having been both a Massachusetts schoolchild and student of historic preservation, this project has inspired and challenged me for the past nine months. To begin, I must thank those who came before me who studied the objects and legacy of the Hancock house. I am greatly indebted to the research efforts of Henry Ayling Phillips (1852- 1926) and Harriette Merrifield Forbes (1856-1951). Their research notes, at the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts served as the launching point for this project. This thesis would not have been possible without the assistance and guidance of my thesis adviser, Brock Jobe. -

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THh INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC ShirleyrEustis Rouse AND/OR COMMON Shirley'-Eustis House LOCATION STREETS NUMBER 31^37 Shirley Street -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Roxbury _ VICINITY OF 12th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 9^ Suffolk 025 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT ^PUBLIC —OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM -^BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X-YES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY x-OTHER unused OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Massachusetts Historical Commission under the administration of ShirleyrEustis Eouse Association_________________________ STREETS NUMBER 4Q Beacon Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Somerset Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston Mas s achtis e t t s REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (14 sheets. 1 29 photos) DATE 1930 f-s 1964. 1939^1963 FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress / Annex Division of Prints and CITY. TOWN STATE Washington n.r DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED —UNALTERED __ORIGINALSITE _GOOD _RUINS ^ALTERED DATE. -FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The house, constructed from 1741 to 1756 for Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts became somewhat of a colonial showplace with its imposing facades and elaborate interior designs. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1950, Volume 45, Issue No. 1

MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE -. % * ,#^iPB P^jJl ?3 ^I^PQPQI H^^yjUl^^ ^_Z ^_^^.: •.. : ^ t lj^^|j|| tm *• Perry Hall, Baltimore County, Home of Harry Dorsey Gough Central Part Built 1773, Wings Added 1784 MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY BALTIMORE larch - 1950 Jft •X'-Jr t^r Jfr Jr J* A* JU J* Jj* Jl» J* Jt* ^tuiy <j» J» Jf A ^ J^ ^ A ^ A •jr J» J* *U J^ ^t* J*-JU'^ Jfr J^ J* »jnjr «jr Jujr «V Jp J(r Jfr Jr Jfr J* «jr»t JUST PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY HISTORY OF QUEEN ANNE'S COUNTY, MARYLAND By FREDERIC EMORY First printed in 1886-87 in the columns of the Centre- ville Observer, this authoritative history of one of the oldest counties on the Eastern Shore, has now been issued in book form. It has been carefully indexed and edited. 629 pages. Cloth binding. $7.50 per copy. By mail $7.75. Published with the assistance of the Queen Anne's County Free Library by the MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY 201 W. MONUMENT STREET BALTIMORE 1 •*••*••*•+•(•'t'+'t-T',trTTrTTTr"r'PTTTTTTTTTTrrT,f'»-,f*"r-f'J-TTT-ft-4"t"t"t"t--t-l- CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING Dftrkxr-BTKrTVTMn FRANK W. LINNEMANN BOOKBINDING 2^ Park Ave Magazines, medical books. Old books rebound PHOTOGRAPHY THE "^^^^ 213 West Monument Street, Baltimore nvr^m^xm > m» • ^•» -, _., ..-•-... „ Baltimore Photo & Blue Print Co PHOTOSTATS & BLUEPRINTS 211 East Baltimore St. Photo copying of old records, genealogical charts LE 688I and family papers. Enlargements. Coats of Arms. PLUMBING — HEATING M. NELSON BARNES Established 1909 BE. -

Ocm01251790-1863.Pdf (10.24Mb)

u ^- ^ " ±i t I c Hon. JONATHAN E. FIELD, President. 1. —George Dwight. IJ. — K. M. Mason. 1. — Francis Briwiej'. ll.-S. .1. Beal. 2.— George A. Shaw. .12 — Israel W. Andrews. 2.—Thomas Wright. 12.-J. C. Allen. 3. — W. F. Johnson. i'i. — Mellen Chamberlain 3.—H. P. Wakefield. 13.—Nathan Crocker. i.—J. E. Crane. J 4.—Thomas Rice, .Ir. 4.—G. H. Gilbert. 14.—F. M. Johnson. 5.—J. H. Mitchell. 15.—William L. Slade. 5. —Hartley Williams. 15—H. M. Richards. 6.—J. C. Tucker. 16. —Asher Joslin. 6.—M. B. Whitney. 16.—Hosea Crane. " 7. —Benjamin Dean. 17.— Albert Nichols. 7.—E. O. Haven. 17.—Otis Gary. 8.—William D. Swan. 18.—Peter Harvey. 8.—William R. Hill. 18.—George Whitney. 9.—.]. I. Baker. 19.—Hen^^' Carter. 9.—R. H. Libby. 19.—Robert Crawford. ]0.—E. F. Jeiiki*. 10.-—Joseph Breck. 20. —Samuel A. Brown. .JOHN MORIS?5KV, Sevii^aiU-ut-Anns. S. N. GIFFORU, aerk. Wigatorn gaHei-y ^ P=l F ISSu/faT-fii Lit Coiranoittoralllj of llitss3t|ttsttts. MANUAL FOR THE USE OF THE G-ENERAL COURT: CONTAINING THE RULES AND ORDERS OF THE TWO BRANCHES, TOGETHER WITH THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH, AND THAT OF THE UNITED STATES, A LIST OF THE EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE, AND JUDICIAL DEPARTMENTS OF THE STATE GOVERNMENT, STATE INSTITUTIONS AND THEIR OFFICERS, COUNTY OFFICERS, AND OTHER STATISTICAL INFORMATION. Prepared, pursuant to Orders of the Legislature, BY S. N. GIFFORD and WM. S. ROBINSON. BOSTON: \yRIGHT & POTTER, STATE PRINTERS, No. 4 Spring Lane. 1863. CTommonbtaltfj of iBnssacf)useits. -

John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: a Reappraisal.”

The Historical Journal of Massachusetts “John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: A Reappraisal.” Author: Arthur Scherr Source: Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 46, No. 1, Winter 2018, pp. 114-159. Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/number/date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/. 114 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2018 John Adams Portrait by Gilbert Stuart, c. 1815 115 John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: A Reappraisal ARTHUR SCHERR Editor's Introduction: The history of religious freedom in Massachusetts is long and contentious. In 1833, Massachusetts was the last state in the nation to “disestablish” taxation and state support for churches.1 What, if any, impact did John Adams have on this process of liberalization? What were Adams’ views on religious freedom and how did they change over time? In this intriguing article Dr. Arthur Scherr traces the evolution, or lack thereof, in Adams’ views on religious freedom from the writing of the original 1780 Massachusetts Constitution to its revision in 1820. He carefully examines contradictory primary and secondary sources and seeks to set the record straight, arguing that there are many unsupported myths and misconceptions about Adams’ role at the 1820 convention. -

Building Order on Beacon Hill, 1790-1850

BUILDING ORDER ON BEACON HILL, 1790-1850 by Jeffrey Eugene Klee A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History Spring 2016 © 2016 Jeffrey Eugene Klee All Rights Reserved ProQuest Number: 10157856 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 10157856 Published by ProQuest LLC (2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 BUILDING ORDER ON BEACON HILL, 1790-1850 by Jeffrey Eugene Klee Approved: __________________________________________________________ Lawrence Nees, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Art History Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Bernard L. Herman, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

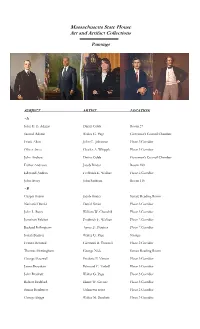

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C. -

Annual Report July 2018–June 2019 Contents

Annual Report July 2018–June 2019 Contents MHS by the Numbers ii Year in Review 1 Impact: National History Day 2 Acquisition Spotlight 4 Why the MHS? 7 New Acquisitions 8 In Memoriam: Amalie M. Kass 10 LOCATION What’s the Buzz around the MHS? 12 1154 Boylston Street Boston, MA 02215 Financials 14 CONTACT Donors 16 Tel: 617.536.1608 Fax: 617.859.0074 Trustees and Overseers 21 VISITOR INFORMATION Fellows 22 Gallery Hours: Mon., Wed., Thu., Fri., and Sat.: 10:00 am Committees 26 to 4:00 pm Tue.: 10:00 am to 7:00 pm Library Hours: The mission of the Massachusetts Historical Society is to promote Mon., Wed., Thu., and Fri.: 9:00 am understanding of the history of Massachusetts and the nation by to 4:45 pm collecting and communicating materials and resources that foster Tue.: 9:00 am to 7:45 pm Sat.: 9:00 am to 3:30 pm historical knowledge. SOCIAL AND WEB @MHS1791 @MassachusettsHistoricalSociety Cover: Ruth Loring by by Sarah Gooll Putnam, circa 1896–1897. Above: Show-and-tell with the staff of the Office of Attorney General Maura Healey, before the event Robert www.masshist.org Treat Paine’s Life and Influence on Law, December 11, 2018 i BY THE Year in Review FY2019 NUMBERS Reaching out, thinking big, and making history—what a year it has been for the MHS! RECORD-BREAKING We welcomed new staff and new Board members, connected with multiple audiences, processed 152 linear ACQUIRED LINEAR FEET OF MANUSCRIPT MATERIAL feet of material, welcomed researchers from around the world, and broke fundraising records at our new 1GALA 352 Making History Gala all while strategizing about our future. -

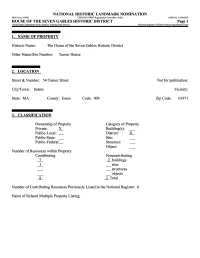

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 HOUSE OF THE SEVEN GABLES HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_________________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: The House of the Seven Gables Historic District Other Name/Site Number: Turner House 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 54 Turner Street Not for publication: City/Town: Salem Vicinity: State: MA County: Essex Code: 009 Zip Code: 01971 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X_ Building(s): __ Public-Local: _ District: 2L_ Public-State: _ Site: __ Public-Federal:_ Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 7 2 buildings 1 _ sites _ structures _ objects 2 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 8 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 HOUSE OF THE SEVEN GABLES HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

2017 Program in New England Studies Schedule Monday, June 19 – Saturday, June 24

2017 Program in New England Studies Schedule Monday, June 19 – Saturday, June 24 Schedule subject to change Monday, June 19: Seventeenth-Century Massachusetts Bay Tuesday, June 20: Eighteenth-Century Piscataqua Wednesday, June 21: Eighteenth Century Thursday, June 22: Nineteenth Century Friday, June 23: Victorian Era Saturday, June 24: Colonial Revival Monday, June 19: Seventeenth-Century Massachusetts Bay 9:30 a.m. Breakfast and Registration at Otis House in Boston 10:00 a.m. Welcome and Orientation 10:15 a.m. How Colonial New England Became Britain’s Pottery Barn Cary Carson, Vice President, Research Division (retired), Colonial Williamsburg Foundation 11:30 a.m. Seventeenth-Century Architecture Claire Dempsey, Associate Professor of American and New England Studies, Boston University 12:45 p.m. Lunch 1:15 p.m. Depart for Saugus, Mass. 2:00 p.m. Tours of Boardman House (c. 1687), Saugus, Mass., and Gedney House (1665), Salem, Mass. Cary Carson and Ben Haavik, Team Leader, Property Care, Historic New England 5:30 p.m. Return to Boston Tuesday, June 20: Eighteenth-Century Piscataqua 7:45 a.m. Depart Otis House for Portsmouth, N.H. 2017 Program in New England Studies Schedule Monday, June 19 – Saturday, June 24 9:00 a.m. Eighteenth-Century Architecture James L. Garvin, State Architectural Historian (retired), New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources 10:30 a.m. Tour of Moffatt-Ladd House (1763) Barbara McLean Ward, Ph.D., Director and Curator, Moffatt-Ladd House and Garden and James L. Garvin Noon Lunch at Moffatt-Ladd House 1:00 p.m. New England House and Home Jane C. -

Rambles in Old Boston, New England

INDEX. ABBOTT, 'BENJAMIN, house and bequest, Il~ Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company: Abbott Hall, 116- founders, 10; armory, s8 j charter-member, Abington, Mass., chaise-hire, 330. 68; drummer, 100; Major Bray, 153. Abrahams, Benjamin, house, 287. Ancient Tunnel (,. fl.), 265-267. Abrams, William, a centenarian. '25. Ancient Weathercock (,. fl.): paper, 332-338; Adams, President John: bust, s8; adherents, Croswell's poem, 332, 333; material and eyes, 70. 333; repairs, 333, 334; liberality, 335; verses Adams, John, house, 117. from the Latin, 335-338. (See Vants.) Adams, John Quincy, portrait, 57. Anderson, John F., aid, x. Adams, Philip, hoU»e, 109. Andirons, brass, 207. Adams Residence, 107-110. (See We/Is.) Andover, Mass., political meeting, 99. Adams, Samuel: stirring speeches, 12; governor- Andrew, John Albion, portrait, 57. ship, 13; portrait, 57; interview with Revere, Andros, Lady, grave, 370. 98, 99; club, 27 2 ; request, 325; grave, 370; Andros, Sir Edmund: governorship, 10; trou heading committee, 393. bles, 255; interest in Chapel, J6s; demand, Adams, Thonla5, estate, 124. 392• Adan Estate, 349. Anne, Queen: birthday, 96; reign, ]66. Adan, John R., positions, J48. Ann Street: a mission, 307; vane, 333; draw- African Joe, violin, 68- bridge, 349; inn and mail, 350. Agassiz, Louis: fossils reconstructed, 344; lit- Ann-Streeters, fight, 257. erary resort, ,386. Antiquarian Authority, 268. Air-furnace, Revere's, 324 Apothecary's Corner, 384. Aldermen, London, 204. Appleton, Lydia, marriage, 109 Ale, sold in English fashion, 358. Appleton, Miss G., aid, x. Alger, Rev. William R., pastorate, 299 Appleton, Mrs., gift of vane, 377. AJlen & Ticknor, bookstore, 385. Appleton's Journal, article in, 71.