The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and the Law in Colonial Maryland, 1648-1715 Monica C

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects "Justice Without Partiality": Women and the Law in Colonial Maryland, 1648-1715 Monica C. Witkowski Marquette University Recommended Citation Witkowski, Monica C., ""Justice Without Partiality": Women and the Law in Colonial Maryland, 1648-1715" (2010). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 27. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/27 “JUSTICE WITHOUT PARTIALITY”: WOMEN AND THE LAW IN COLONIAL MARYLAND, 1648-1715 by Monica C. Witkowski A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2010 ABSTRACT “JUSTICE WITHOUT PARTIALITY”: WOMEN AND THE LAW IN COLONIAL MARYLAND, 1648-1715 Monica C. Witkowski Marquette University, 2010 What was the legal status of women in early colonial Maryland? This is the central question answered by this dissertation. Women, as exemplified through a series of case studies, understood the law and interacted with the nascent Maryland legal system. Each of the cases in the following chapters is slightly different. Each case examined in this dissertation illustrates how much independent legal agency women in the colony demonstrated. Throughout the seventeenth century, Maryland women appeared before the colony’s Provincial and county courts as witnesses, plaintiffs, defendants, and attorneys in criminal and civil trials. Women further entered their personal cattle marks, claimed land, and sued other colonists. This study asserts that they improved their social standing through these interactions with the courts. By exerting this much legal knowledge, they created an important place for themselves in Maryland society. Historians have begun to question the interpretation that Southern women were restricted to the home as housewives and mothers. -

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NANTUCKET HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Nantucket Historic District Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Not for publication: City/Town: Nantucket Vicinity: State: MA County: Nantucket Code: 019 Zip Code: 02554, 02564, 02584 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): Public-Local: X District: X Public-State: Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 5,027 6,686 buildings sites structures objects 5,027 6,686 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 13,188 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NANTUCKET HISTORIC DISTRICT Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Colonial America

COLONIAL AMERICA 1651 DOCUMENT SIGNED BY TIMOTHY HATHERLY, WITCH TRIAL MAGISTRATE AND MASSACHUSETTS MERCHANT ADVENTURER WHO FINANCED THE BAY COLONY GOVERNOR THOMAS PRENCE SIGNS A COLONY AT PLYMOUTH 1670 DEPOSITION * 1 [COLONIAL PLYMOUTH] TIMOTHY HATHERLY was * 2 one of the Merchant Adventurers of London who financed the [COLONIAL PLYMOUTH] THOMAS PRENCE: Governor colony at Plymouth, Massachusetts after obtaining a patent from Massachusetts Bay colony. Arrived at Plymouth Colony on the “For- King James covering all of the Atlantic coast of America from the tune” in 1621. He was one of the first settlers of Nansett, or grant to the Virginia company on the south, to and including New- Eastham, was chosen the first governor of Governor of Massachu- foundland. Hatherly was one of the few Adventurers to actually setts Bay Colony in 1633. serving until 1638, and again from 1657 till settle in America. He arrived in 1623 on the ship Ann, then returned 1673, and was an assistant in 1635-’7 and 1639-’57. Governor Prence to England in 1625. In 1632, he came back to Plymouth and in 1637 also presided over a witch trial in 1661 and handled it “sanely and was one of the recipients of a tract of land at Scituate. Before 1646, with reason.” He also presided over the court when the momen- Hatherly had bought out the others and had formed a stock com- tous decision was made to execute a colonist who had murdered an pany, called the “Conihasset Partners.” Scituate was part of the Ply- Indian. He was an impartial magistrate, was distinguished for his mouth Colony; it was first mentioned in William Bradford’s writ- religious zeal, and opposed those that he believed to be heretics, ings about 1634. -

Introduction, the Constitution of the State of Connecticut

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU Government, Politics & Global Studies Faculty Government, Politics & Global Studies Publications 2011 Introduction, The onsC titution of the State of Connecticut Gary L. Rose Sacred Heart University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/gov_fac Part of the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Rose, Gary L., "Introduction, The onC stitution of the State of Connecticut" (2011). Government, Politics & Global Studies Faculty Publications. Paper 2. http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/gov_fac/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Government, Politics & Global Studies at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Government, Politics & Global Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTRODUCTION Connecticut license plates boldly bear the inscription, “the Constitution State.” This is due to Connecticut’s long and proud tradition of self-government under the protection of a written constitution. Connecticut’s constitutional tradition can be traced to the Fundamental Orders of 1639. Drafted by repre- sentatives from the three Connecticut River towns of Hartford, Wethersfi eld and Windsor, the Fundamental Orders were the very fi rst constitution known to humankind. The Orders were drafted completely free of British infl uence and established what can be considered as the fi rst self-governing colony in North America. Moreover, Connecticut’s Fundamental Orders can be viewed as the foundation for constitutional government in the western world. In 1662, the Fundamental Orders were replaced by a Royal Charter. Granted to Connecticut by King Charles II, the Royal Charter not only embraced the principles of the Fundamental Orders, but also formally recognized Connecticut’s system of self-government. -

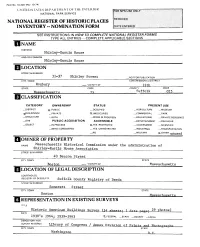

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THh INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC ShirleyrEustis Rouse AND/OR COMMON Shirley'-Eustis House LOCATION STREETS NUMBER 31^37 Shirley Street -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Roxbury _ VICINITY OF 12th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 9^ Suffolk 025 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT ^PUBLIC —OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM -^BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X-YES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY x-OTHER unused OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Massachusetts Historical Commission under the administration of ShirleyrEustis Eouse Association_________________________ STREETS NUMBER 4Q Beacon Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Somerset Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston Mas s achtis e t t s REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (14 sheets. 1 29 photos) DATE 1930 f-s 1964. 1939^1963 FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress / Annex Division of Prints and CITY. TOWN STATE Washington n.r DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED —UNALTERED __ORIGINALSITE _GOOD _RUINS ^ALTERED DATE. -FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The house, constructed from 1741 to 1756 for Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts became somewhat of a colonial showplace with its imposing facades and elaborate interior designs. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1950, Volume 45, Issue No. 1

MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE -. % * ,#^iPB P^jJl ?3 ^I^PQPQI H^^yjUl^^ ^_Z ^_^^.: •.. : ^ t lj^^|j|| tm *• Perry Hall, Baltimore County, Home of Harry Dorsey Gough Central Part Built 1773, Wings Added 1784 MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY BALTIMORE larch - 1950 Jft •X'-Jr t^r Jfr Jr J* A* JU J* Jj* Jl» J* Jt* ^tuiy <j» J» Jf A ^ J^ ^ A ^ A •jr J» J* *U J^ ^t* J*-JU'^ Jfr J^ J* »jnjr «jr Jujr «V Jp J(r Jfr Jr Jfr J* «jr»t JUST PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY HISTORY OF QUEEN ANNE'S COUNTY, MARYLAND By FREDERIC EMORY First printed in 1886-87 in the columns of the Centre- ville Observer, this authoritative history of one of the oldest counties on the Eastern Shore, has now been issued in book form. It has been carefully indexed and edited. 629 pages. Cloth binding. $7.50 per copy. By mail $7.75. Published with the assistance of the Queen Anne's County Free Library by the MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY 201 W. MONUMENT STREET BALTIMORE 1 •*••*••*•+•(•'t'+'t-T',trTTrTTTr"r'PTTTTTTTTTTrrT,f'»-,f*"r-f'J-TTT-ft-4"t"t"t"t--t-l- CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING Dftrkxr-BTKrTVTMn FRANK W. LINNEMANN BOOKBINDING 2^ Park Ave Magazines, medical books. Old books rebound PHOTOGRAPHY THE "^^^^ 213 West Monument Street, Baltimore nvr^m^xm > m» • ^•» -, _., ..-•-... „ Baltimore Photo & Blue Print Co PHOTOSTATS & BLUEPRINTS 211 East Baltimore St. Photo copying of old records, genealogical charts LE 688I and family papers. Enlargements. Coats of Arms. PLUMBING — HEATING M. NELSON BARNES Established 1909 BE. -

The Legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1987 The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony Michael J. Puglisi College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Puglisi, Michael J., "The legacies of King Philip's War in the Massachusetts Bay Colony" (1987). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623769. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-f5eh-p644 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print. -

Thomas Prince, the Puritan Past, and New England's Future, 1660-1736

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2011 The Wondrous Chain of Providence: Thomas Prince, the Puritan Past, and New England's Future, 1660-1736 Thomas Joseph Gillan College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Gillan, Thomas Joseph, "The Wondrous Chain of Providence: Thomas Prince, the Puritan Past, and New England's Future, 1660-1736" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626655. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-rkeb-ec16 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Wondrous Chain of Providence: Thomas Prince, the Puritan Past, and New England’s Future, 1660-1736 Thomas Joseph Gillan Winter Springs, Florida Bachelor of Arts, University of Central Florida, 2008 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Lyon G. Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary May 2011 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Thomas Joseph GillaiT"'J Approved by the Com^^ ^ ^ March, 2011 Committee Chair Associate Professor Chandos M. Brown, History The College of WrNiam and Mary Professor Ifhristopher Grasso, History The College of William and Mary Assistant Professor Nicholas S. -

Mid-Term Exam Study Guide, Fall Semester 2019 Know The

Mid-Term Exam Study Guide, Fall Semester 2019 Know the significance of the following terms, including the definition of each and its significance in the overall context of American history. Use your Powerpoint notes, study guides, returned tests and quizzes, and book to study for this mid-term. You may use one of the following as a “cheat sheet” to bring to the exam: a) 8½”x11” piece of paper, front only, b) two 3”x5” note cards, front and back, or c) a single 5”x7” note card, front and back. It must be hand-written and must be turned in after the mid-term. Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Francisco Coronado Covenant Archaeology Commercial Revolution Juan Cabrillo General Court Bering Strait Land Bridge Capital Council of the Indies Connecticut Ice Age Joint-Stock Companies Viceroys Thomas Hooker Artifacts Black Death Pueblos Fundamental Orders of Migration The Renaissance Missions Connecticut Paleo-Indians Leonardo da Vinci Presidios Rhode Island Hunter-Gatherers Michaelangelo Encomienda System Roger Williams Nomadic Galileo Galilei Bartolome de las Casas Anne Hutchinson Domestication Nicolas Copernicus Plantations Salem Witch Trials Agriculture Johannes Gutenberg Borderlands Maryland Environments Printing press Juan de Onate Cecilius Calvert (Lord Civilization Henry the Navigator El Camino Real Baltimore) Culture Astrolabe Peninsulares Toleration Act of 1649 Societies Compass Mestizos Pennsylvania Glyphs Caravel Criollos Quakers Anasazi Bartolomeu Dias Martin Luther William Penn Hopewell Culture Vasco de Gama Protestant Reformation Proprietary colony -

For All the People

Praise for For All the People John Curl has been around the block when it comes to knowing work- ers’ cooperatives. He has been a worker owner. He has argued theory and practice, inside the firms where his labor counts for something more than token control and within the determined, but still small uni- verse where labor rents capital, using it as it sees fit and profitable. So his book, For All the People: The Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America, reached expectant hands, and an open mind when it arrived in Asheville, NC. Am I disappointed? No, not in the least. Curl blends the three strands of his historical narrative with aplomb, he has, after all, been researching, writing, revising, and editing the text for a spell. Further, I am certain he has been responding to editors and publishers asking this or that. He may have tired, but he did not give up, much inspired, I am certain, by the determination of the women and men he brings to life. Each of his subtitles could have been a book, and has been written about by authors with as many points of ideological view as their titles. Curl sticks pretty close to the narrative line written by worker own- ers, no matter if they came to work every day with a socialist, laborist, anti-Marxist grudge or not. Often in the past, as with today’s worker owners, their firm fails, a dream to manage capital kaput. Yet today, as yesterday, the democratic ideals of hundreds of worker owners support vibrantly profitable businesses. -

Essex County, Massachusetts, 1630-1768 Harold Arthur Pinkham Jr

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1980 THE TRANSPLANTATION AND TRANSFORMATION OF THE ENGLISH SHIRE IN AMERICA: ESSEX COUNTY, MASSACHUSETTS, 1630-1768 HAROLD ARTHUR PINKHAM JR. University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation PINKHAM, HAROLD ARTHUR JR., "THE TRANSPLANTATION AND TRANSFORMATION OF THE ENGLISH SHIRE IN AMERICA: ESSEX COUNTY, MASSACHUSETTS, 1630-1768" (1980). Doctoral Dissertations. 2327. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2327 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. Whfle the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations vhich may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Catalogue of the Library and Autographs of William F. Johnson

* Copy / I - V CATALD DUE 30 X Ilibr&ry • &nd - OF WILLIAM F. JOHNSON, ESQ., w OK BOSTON, MASS. fVERY VALUABLE and Interesting Collection of English and American Literature comprising, under the title Americana, a num¬ ber of scarce works by the Mathers, Eliot and other authors of their day ; in General Literature, many Standard and Popular Works of Biography, History and Romance, and worthy of especial notice and attention, a Collection of FIRST EDITIONS of REMARKABLE INTEREST AND VALUE BY REASON OF BOTH RARITY AND BEAUTY OF CONDITION, including the most desired specimens of the works of Coleridge, Hunt, Lamb, Keats, Shelley, Thackeray, Browning, Bry¬ ant, Emerson, Hawthorne, Longfellow and others. Also to be mentioned a charming lot of CRUIKSH ANKIANA, and books illustrated by Leech and Rowlandson. In addition to all the book treasures there are Specimen Autographs of the best known and honored English and American Authors, Statesmen and others, many of them particularly desirable for condition or interesting con¬ tents. TO BE SOLD AT AUCTION Monday, Tuesday, "Wednesday and Thursday, JANUARY 2T—30, 1890, BANQS & 60.,,. , * i A ■» 1 > > > • «. it1 > » i ) >) > ) ) > 5 > 1 J > * ) » > 739 & 741 Broadway, New York. 7 ~ % > n > > ) t> ) >7 > SALE TO BEGIN AT 3 O’CLOCK!’ ' > 7 > ' 7 ' > > 7 ) 7 *7 >v > ) , 7 {y Buyers wl~io cannot attend tloe sale me\y have pcir- chases made to tlieir order toy ttie Auctioneers. •* \ in 3 7 . '" i 'O'b ■ 9 c 1 ( f' * ( 0 « C. < C I < < < I / I , < C l < C » c 1 « l ( 1C. C f «. < « c c c i r < < < < 6 < C < < C \ ( < « ( V ( c C ( < < < < C C C t C.