Thomas Prince, the Puritan Past, and New England's Future, 1660-1736

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and the Law in Colonial Maryland, 1648-1715 Monica C

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects "Justice Without Partiality": Women and the Law in Colonial Maryland, 1648-1715 Monica C. Witkowski Marquette University Recommended Citation Witkowski, Monica C., ""Justice Without Partiality": Women and the Law in Colonial Maryland, 1648-1715" (2010). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 27. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/27 “JUSTICE WITHOUT PARTIALITY”: WOMEN AND THE LAW IN COLONIAL MARYLAND, 1648-1715 by Monica C. Witkowski A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2010 ABSTRACT “JUSTICE WITHOUT PARTIALITY”: WOMEN AND THE LAW IN COLONIAL MARYLAND, 1648-1715 Monica C. Witkowski Marquette University, 2010 What was the legal status of women in early colonial Maryland? This is the central question answered by this dissertation. Women, as exemplified through a series of case studies, understood the law and interacted with the nascent Maryland legal system. Each of the cases in the following chapters is slightly different. Each case examined in this dissertation illustrates how much independent legal agency women in the colony demonstrated. Throughout the seventeenth century, Maryland women appeared before the colony’s Provincial and county courts as witnesses, plaintiffs, defendants, and attorneys in criminal and civil trials. Women further entered their personal cattle marks, claimed land, and sued other colonists. This study asserts that they improved their social standing through these interactions with the courts. By exerting this much legal knowledge, they created an important place for themselves in Maryland society. Historians have begun to question the interpretation that Southern women were restricted to the home as housewives and mothers. -

Colonial America

COLONIAL AMERICA 1651 DOCUMENT SIGNED BY TIMOTHY HATHERLY, WITCH TRIAL MAGISTRATE AND MASSACHUSETTS MERCHANT ADVENTURER WHO FINANCED THE BAY COLONY GOVERNOR THOMAS PRENCE SIGNS A COLONY AT PLYMOUTH 1670 DEPOSITION * 1 [COLONIAL PLYMOUTH] TIMOTHY HATHERLY was * 2 one of the Merchant Adventurers of London who financed the [COLONIAL PLYMOUTH] THOMAS PRENCE: Governor colony at Plymouth, Massachusetts after obtaining a patent from Massachusetts Bay colony. Arrived at Plymouth Colony on the “For- King James covering all of the Atlantic coast of America from the tune” in 1621. He was one of the first settlers of Nansett, or grant to the Virginia company on the south, to and including New- Eastham, was chosen the first governor of Governor of Massachu- foundland. Hatherly was one of the few Adventurers to actually setts Bay Colony in 1633. serving until 1638, and again from 1657 till settle in America. He arrived in 1623 on the ship Ann, then returned 1673, and was an assistant in 1635-’7 and 1639-’57. Governor Prence to England in 1625. In 1632, he came back to Plymouth and in 1637 also presided over a witch trial in 1661 and handled it “sanely and was one of the recipients of a tract of land at Scituate. Before 1646, with reason.” He also presided over the court when the momen- Hatherly had bought out the others and had formed a stock com- tous decision was made to execute a colonist who had murdered an pany, called the “Conihasset Partners.” Scituate was part of the Ply- Indian. He was an impartial magistrate, was distinguished for his mouth Colony; it was first mentioned in William Bradford’s writ- religious zeal, and opposed those that he believed to be heretics, ings about 1634. -

The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1970 The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740 Ronald P. Dufour College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Dufour, Ronald P., "The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740" (1970). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624699. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ssac-2z49 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEE DEVELOPMENT OF POLITICAL THEORY IN COLONIAL MASSACHUSETTS 1688 - 17^0 A Th.esis Presented to 5he Faculty of the Department of History 5he College of William and Mary in Virginia In I&rtial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Ronald P. Dufour 1970 ProQ uest Number: 10625131 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10625131 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. -

Surviving the First Year of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, 1630-1631 Memoir of Roger Clap, Ca

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox American Beginnings: The European Presence in North America, 1492-1690 Marguerite Mullaney Nantasket Beach, Massachusetts, May “shift for ourselves in a forlorn place in this wilderness” Surviving the First Year of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, 1630-1631 Memoir of Roger Clap, ca. 1680s, excerpts * Roger Clap [Clapp] arrived in New England in May 1630 at age 21, having overcome his father's opposition to his emigration. In his seventies he began his memoir to tell his children of "God's remarkable providences . in bringing me to this land." A devout man, he interprets the lack of food for his body as part of God's providing food for the soul, in this case the souls of the Puritans as they created their religious haven. thought good, my dear children, to leave with you some account of God’s remarkable providences to me, in bringing me into this land and placing me here among his dear servants and in his house, who I am most unworthy of the least of his mercies. The Scripture requireth us to tell God’s wondrous works to our children, that they may tell them to their children, that God may have glory throughout all ages. Amen. I was born in England, in Sallcom, in Devonshire, in the year of our Lord 1609. My father was a man fearing God, and in good esteem among God’s faithful servants. His outward estate was not great, I think not above £80 per annum.1 We were five brethren (of which I was the youngest) and two sisters. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

Exploring Boston's Religious History

Exploring Boston’s Religious History It is impossible to understand Boston without knowing something about its religious past. The city was founded in 1630 by settlers from England, Other Historical Destinations in popularly known as Puritans, Downtown Boston who wished to build a model Christian community. Their “city on a hill,” as Governor Old South Church Granary Burying Ground John Winthrop so memorably 645 Boylston Street Tremont Street, next to Park Street put it, was to be an example to On the corner of Dartmouth and Church, all the world. Central to this Boylston Streets Park Street T Stop goal was the establishment of Copley T Stop Burial Site of Samuel Adams and others independent local churches, in which all members had a voice New North Church (Now Saint Copp’s Hill Burying Ground and worship was simple and Stephen’s) Hull Street participatory. These Puritan 140 Hanover Street Haymarket and North Station T Stops religious ideals, which were Boston’s North End Burial Site of the Mathers later embodied in the Congregational churches, Site of Old North Church King’s Chapel Burying Ground shaped Boston’s early patterns (Second Church) Tremont Street, next to King’s Chapel of settlement and government, 2 North Square Government Center T Stop as well as its conflicts and Burial Site of John Cotton, John Winthrop controversies. Not many John Winthrop's Home Site and others original buildings remain, of Near 60 State Street course, but this tour of Boston’s “old downtown” will take you to sites important to the story of American Congregationalists, to their religious neighbors, and to one (617) 523-0470 of the nation’s oldest and most www.CongregationalLibrary.org intriguing cities. -

Historic Houses of Worship in Boston's Back Bay David R. Bains, Samford

Historic Houses of Worship in Boston’s Back Bay David R. Bains, Samford University Jeanne Halgren Kilde, University of Minnesota 1:00 Leave Hynes Convention Center Walk west (left) on Boylston to Mass. Ave. Turn left on Mass. Ave. Walk 4 blocks 1:10 Arrive First Church of Christ Scientist 2:00 Depart for Trinity Church along reflecting pool and northeast on Huntington Old South Church and Boston Public Library are visible from Copley Square 2:15 Arrive Trinity Church 3:00 Depart for First Lutheran Walk north on Clarendon St. past Trinity Church Rectory (n.e. corner of Newbury and Clarendon) First Baptist Church (s.w. corner of Commonwealth and Clarendon) Turn right on Commonwealth, Turn left on Berkley. First Church is across from First Lutheran 3:15 Arrive First Lutheran 3:50 Depart for Emmanuel Turn left on Berkeley Church of the Covenant is at the corner of Berkley and Newbury Turn left on Newbury 4:00 Arrive Emmanuel Church 4:35 Depart for Convention Center Those wishing to see Arlington Street Church should walk east on Newbury to the end of the block and then one block south on Arlington. Stops are in bold; walk-bys are underlined Eight streets that run north-to-south (perpendicular to the Charles) are In 1857, the bay began to be filled, The ground we are touring was completed by arranged alphabetically from Arlington at the East to Hereford at the West. 1882, the entire bay to near Kenmore Sq. by 1890. The filling eliminated ecologically valuable wetlands but created Boston’s premier Victorian The original city of Boston was located on the Shawmut Peninsula which was neighborhood. -

Catalogue of the Library and Autographs of William F. Johnson

* Copy / I - V CATALD DUE 30 X Ilibr&ry • &nd - OF WILLIAM F. JOHNSON, ESQ., w OK BOSTON, MASS. fVERY VALUABLE and Interesting Collection of English and American Literature comprising, under the title Americana, a num¬ ber of scarce works by the Mathers, Eliot and other authors of their day ; in General Literature, many Standard and Popular Works of Biography, History and Romance, and worthy of especial notice and attention, a Collection of FIRST EDITIONS of REMARKABLE INTEREST AND VALUE BY REASON OF BOTH RARITY AND BEAUTY OF CONDITION, including the most desired specimens of the works of Coleridge, Hunt, Lamb, Keats, Shelley, Thackeray, Browning, Bry¬ ant, Emerson, Hawthorne, Longfellow and others. Also to be mentioned a charming lot of CRUIKSH ANKIANA, and books illustrated by Leech and Rowlandson. In addition to all the book treasures there are Specimen Autographs of the best known and honored English and American Authors, Statesmen and others, many of them particularly desirable for condition or interesting con¬ tents. TO BE SOLD AT AUCTION Monday, Tuesday, "Wednesday and Thursday, JANUARY 2T—30, 1890, BANQS & 60.,,. , * i A ■» 1 > > > • «. it1 > » i ) >) > ) ) > 5 > 1 J > * ) » > 739 & 741 Broadway, New York. 7 ~ % > n > > ) t> ) >7 > SALE TO BEGIN AT 3 O’CLOCK!’ ' > 7 > ' 7 ' > > 7 ) 7 *7 >v > ) , 7 {y Buyers wl~io cannot attend tloe sale me\y have pcir- chases made to tlieir order toy ttie Auctioneers. •* \ in 3 7 . '" i 'O'b ■ 9 c 1 ( f' * ( 0 « C. < C I < < < I / I , < C l < C » c 1 « l ( 1C. C f «. < « c c c i r < < < < 6 < C < < C \ ( < « ( V ( c C ( < < < < C C C t C. -

Hclassifi Cation

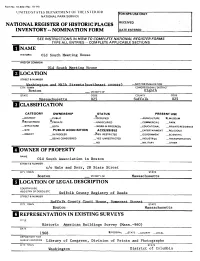

Form No 10-300 (Rev 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FOR NPS USE GNtY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVE!} INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC old South Meeting House AND/OR COMMON Old South Meeting House Q LOCATION STREETS NUMBER Washington and Milk Streets ("northeast corner) _ NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Boston _ VICINITY OF Eighth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Suffolk 025 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT _PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM ^BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS -2VES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED — INDUSTRIAL _ TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Old South Association in Boston STREETS NUMBER c/o Hale and Dorr, 28 State Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Suffolk County Court House Somprspt Strppt CITY, TOWN STATE Boston Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS Historic American Buildings Survey (Mass.-960) DATE 1968 X-FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Division of Prints and Photographs CITY, TOWN STATE W&shington District of Columbia DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS _XALTERED _MOVED DATE_____ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Old South Meeting House, located at the northeast corner of Washington and Milk Streets in downtown Boston, was built as the second home of the Third Church in Boston, gathered in 1669. -

WILLARD, Samuel, Vice President of Harvard College, Born at Concord, Massachusetts, January 31, 1640, Was a Son of Simon Willard, a Man of Considerable Distinction

PEOPLE MENTIONED IN CAPE COD 1 CONCORD’S “NATIVE” COLLEGE GRADS: REVEREND SAMUEL SYMON WILLARD “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY 1. Only those native to (which is to say, born in) Concord, Massachusetts — and among those accomplished natives, only those whose initials are not HDT. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE PEOPLE OF CAPE COD:REVEREND SAMUEL SYMON WILLARD PEOPLE MENTIONED IN CAPE COD CAPE COD: After his marriage with the daughter of Mr. Willard PEOPLE OF (pastor of the South Church in Boston), he was sometimes invited CAPE COD by that gentleman to preach in his pulpit. Mr. Willard possessed a graceful delivery, a masculine and harmonious voice; and, though he did not gain much reputation by his ‘Body of Divinity,’ which is frequently sneered at, particularly by those who have not read it, yet in his sermons are strength of thought, and energy of language. The natural consequence was that he was generally admired. Mr. Treat having preached one of his best discourses to the congregation of his father-in-law, in his usual unhappy manner, excited universal disgust; and several nice judges waited on Mr. Willard, and begged that Mr. Treat, who was a worthy, pious man, it was true, but a wretched preacher, might never be invited into his pulpit again. To this request Mr. Willard made no reply; but he desired his son-in-law to lend him the discourse; which, being left with him, he delivered it without alteration, to his people, a few weeks after. They ran to Mr. -

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies BY BABETTE M. LEVY Preface NE of the pleasant by-products of doing research O work is the realization of how generously help has been given when it was needed. The author owes much to many people who proved their interest in this attempt to see America's past a little more clearly. The Institute of Early American History and Culture gave two grants that enabled me to devote a sabbatical leave and a summer to direct searching of colony and church records. Librarians and archivists have been cooperative beyond the call of regular duty. Not a few scholars have read the study in whole or part to give me the benefit of their knowledge and judgment. I must mention among them Professor Josephine W, Bennett of the Hunter College English Department; Miss Madge McLain, formerly of the Hunter College Classics Department; the late Dr. William W. Rockwell, Librarian Emeritus of Union Theological Seminary, whose vast scholarship and his willingness to share it will remain with all who knew him as long as they have memories; Professor Matthew Spinka of the Hartford Theological Sem- inary; and my mother, who did not allow illness to keep her from listening attentively and critically as I read to her chapter after chapter. All students who are interested 7O AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY in problems concerning the early churches along the Atlantic seaboard and the occupants of their pulpits are indebted to the labors of Dr. Frederick Lewis Weis and his invaluable compendiums on the clergymen and parishes of the various colonies. -

Chapter XII. the Proprietors of Pocasset. Edward Gray, Nathaniel

Chapter XII THE PROPRIETORS OF POCASSET EDWARD GRAY, NATHANIEL THOMAS, BENJAMIN CHURCH , CAPT. CHRISTOPHER ALMY, JOB ALMY, THOMAS WAITE, JR ., DANIEL WILCOX, WILLIAM MANCHESTER Edward Gray The first named of the Pocasset proprietors owned three tenths of th e entire tract. He has many descendants of the same name now living i n our midst who are prominent in professional and social life . He came to Plymouth with a brother Thomas in 1643, at the age of fourteen years . Thomas died in 1654 . It is reputed that these two boys were smuggle d out of England by relatives who desired to retain possession of their in- heritance. In Plymouth Edward became a merchant doing business in a very central location on Main street between Leyden and Middle streets . In 1651 he married Mary, a daughter of John Winslow and Mary Chilto n Winslow. The writer is descended from Mary's sister Susanna who mar- ried Robert Lathan. John Chilton and Mary Chilton, and daughter Mar y who married John Winslow, were Mayflower passengers and John Winslow was a brother of Gov . Edward Winslow . Gray's children by this marriage did not settle in this section . In 1665 Edward Gray married Dorothy, a daughter of Thomas and An n Lettis . Thomas Lettis had deceased leaving to Ann the mother valuabl e lands, also on Main street in Plymouth, and the mother conveyed these to th e daughter, so that Edward Gray would have controlled most central estate s on both sides of Main street, was very prominent and was also considere d to be a wealthy citizen, he was deputy to the general court fro m Plymouth in 1679 and 1680 ; he died in June 1681, so that he probably never visite d the Pocasset lands ; his grave on Burial Hill bears the oldest legible date , yet in spite of his wealth he signed his name by mark, which does not, according to the times, necessarily indicate that he could not read .