The Knowles Riot of 1747 and Transatlantic Opposition to Impressment Jonathan Feld Princeton University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The War of 1812

American flag HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY The War of 1812 Teacher Guide British navy Americans and British make peace American victory on Lake Erie G2T_U7_The War of 1812_TG.indb 1 27/09/19 8:48 PM G2T_U7_The War of 1812_TG.indb 2 27/09/19 8:48 PM The War of 1812 Teacher Guide G2T_U7_The War of 1812_TG.indb 1 27/09/19 8:48 PM Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free: to Share—to copy, distribute, and transmit the work to Remix—to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution—You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation (www.coreknowledge.org) made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial—You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to this web page: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Copyright © 2019 Core Knowledge Foundation www.coreknowledge.org 5 All Rights Reserved. - 3 Core Knowledge®, Core Knowledge Curriculum Series™, Core Knowledge History and Geography™, and CKHG™ are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. -

The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1970 The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740 Ronald P. Dufour College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Dufour, Ronald P., "The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740" (1970). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624699. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ssac-2z49 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEE DEVELOPMENT OF POLITICAL THEORY IN COLONIAL MASSACHUSETTS 1688 - 17^0 A Th.esis Presented to 5he Faculty of the Department of History 5he College of William and Mary in Virginia In I&rtial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Ronald P. Dufour 1970 ProQ uest Number: 10625131 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10625131 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. -

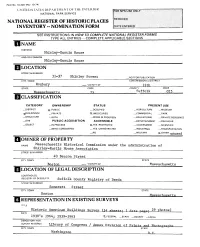

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THh INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC ShirleyrEustis Rouse AND/OR COMMON Shirley'-Eustis House LOCATION STREETS NUMBER 31^37 Shirley Street -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Roxbury _ VICINITY OF 12th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 9^ Suffolk 025 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT ^PUBLIC —OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM -^BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X-YES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY x-OTHER unused OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Massachusetts Historical Commission under the administration of ShirleyrEustis Eouse Association_________________________ STREETS NUMBER 4Q Beacon Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Somerset Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston Mas s achtis e t t s REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (14 sheets. 1 29 photos) DATE 1930 f-s 1964. 1939^1963 FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress / Annex Division of Prints and CITY. TOWN STATE Washington n.r DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED —UNALTERED __ORIGINALSITE _GOOD _RUINS ^ALTERED DATE. -FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The house, constructed from 1741 to 1756 for Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts became somewhat of a colonial showplace with its imposing facades and elaborate interior designs. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1950, Volume 45, Issue No. 1

MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE -. % * ,#^iPB P^jJl ?3 ^I^PQPQI H^^yjUl^^ ^_Z ^_^^.: •.. : ^ t lj^^|j|| tm *• Perry Hall, Baltimore County, Home of Harry Dorsey Gough Central Part Built 1773, Wings Added 1784 MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY BALTIMORE larch - 1950 Jft •X'-Jr t^r Jfr Jr J* A* JU J* Jj* Jl» J* Jt* ^tuiy <j» J» Jf A ^ J^ ^ A ^ A •jr J» J* *U J^ ^t* J*-JU'^ Jfr J^ J* »jnjr «jr Jujr «V Jp J(r Jfr Jr Jfr J* «jr»t JUST PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY HISTORY OF QUEEN ANNE'S COUNTY, MARYLAND By FREDERIC EMORY First printed in 1886-87 in the columns of the Centre- ville Observer, this authoritative history of one of the oldest counties on the Eastern Shore, has now been issued in book form. It has been carefully indexed and edited. 629 pages. Cloth binding. $7.50 per copy. By mail $7.75. Published with the assistance of the Queen Anne's County Free Library by the MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY 201 W. MONUMENT STREET BALTIMORE 1 •*••*••*•+•(•'t'+'t-T',trTTrTTTr"r'PTTTTTTTTTTrrT,f'»-,f*"r-f'J-TTT-ft-4"t"t"t"t--t-l- CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING Dftrkxr-BTKrTVTMn FRANK W. LINNEMANN BOOKBINDING 2^ Park Ave Magazines, medical books. Old books rebound PHOTOGRAPHY THE "^^^^ 213 West Monument Street, Baltimore nvr^m^xm > m» • ^•» -, _., ..-•-... „ Baltimore Photo & Blue Print Co PHOTOSTATS & BLUEPRINTS 211 East Baltimore St. Photo copying of old records, genealogical charts LE 688I and family papers. Enlargements. Coats of Arms. PLUMBING — HEATING M. NELSON BARNES Established 1909 BE. -

Ocm01251790-1863.Pdf (10.24Mb)

u ^- ^ " ±i t I c Hon. JONATHAN E. FIELD, President. 1. —George Dwight. IJ. — K. M. Mason. 1. — Francis Briwiej'. ll.-S. .1. Beal. 2.— George A. Shaw. .12 — Israel W. Andrews. 2.—Thomas Wright. 12.-J. C. Allen. 3. — W. F. Johnson. i'i. — Mellen Chamberlain 3.—H. P. Wakefield. 13.—Nathan Crocker. i.—J. E. Crane. J 4.—Thomas Rice, .Ir. 4.—G. H. Gilbert. 14.—F. M. Johnson. 5.—J. H. Mitchell. 15.—William L. Slade. 5. —Hartley Williams. 15—H. M. Richards. 6.—J. C. Tucker. 16. —Asher Joslin. 6.—M. B. Whitney. 16.—Hosea Crane. " 7. —Benjamin Dean. 17.— Albert Nichols. 7.—E. O. Haven. 17.—Otis Gary. 8.—William D. Swan. 18.—Peter Harvey. 8.—William R. Hill. 18.—George Whitney. 9.—.]. I. Baker. 19.—Hen^^' Carter. 9.—R. H. Libby. 19.—Robert Crawford. ]0.—E. F. Jeiiki*. 10.-—Joseph Breck. 20. —Samuel A. Brown. .JOHN MORIS?5KV, Sevii^aiU-ut-Anns. S. N. GIFFORU, aerk. Wigatorn gaHei-y ^ P=l F ISSu/faT-fii Lit Coiranoittoralllj of llitss3t|ttsttts. MANUAL FOR THE USE OF THE G-ENERAL COURT: CONTAINING THE RULES AND ORDERS OF THE TWO BRANCHES, TOGETHER WITH THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH, AND THAT OF THE UNITED STATES, A LIST OF THE EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE, AND JUDICIAL DEPARTMENTS OF THE STATE GOVERNMENT, STATE INSTITUTIONS AND THEIR OFFICERS, COUNTY OFFICERS, AND OTHER STATISTICAL INFORMATION. Prepared, pursuant to Orders of the Legislature, BY S. N. GIFFORD and WM. S. ROBINSON. BOSTON: \yRIGHT & POTTER, STATE PRINTERS, No. 4 Spring Lane. 1863. CTommonbtaltfj of iBnssacf)useits. -

Rationality, Pirates, and the Law: a Retrospective

LEESON.OFFTOPRINTER.CORREX.SECOND (DO NOT DELETE) 6/17/2010 6:44 PM RATIONALITY, PIRATES, AND THE LAW: A RETROSPECTIVE * PETER T. LEESON TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .......................................................................................1219 I. Antipiracy Law Before 1700 ....................................................1220 II. Antipiracy Law After 1700 .......................................................1222 III. The Hard-Plucked Fruit of Antipiracy Legal Reform and Pirates’ Response .....................................................................1224 Conclusion .........................................................................................1229 INTRODUCTION In the late 1720s, Caribbean piracy was brought to a screeching halt. An enhanced British naval presence was partly responsible for bringing pirates to their end. But the most important factor contributing to this result was a series of early eighteenth-century legal changes that made it possible to prosecute pirates effectively. This short Article’s purpose is to recount those legal changes and document their effectiveness. Its other purpose is to analyze pirates’ response to the legal changes designed to exterminate them, which succeeded, at least partly, in frustrating the British government’s goal. By providing a retrospective look at antipiracy law and pirates’ reactions to that law, my hope is to supply some useful material for thinking about how to use the law to address the contemporary piracy problem. * Visiting Professor of Economics, -

Was The War of 1812. Impressment (Or Impressing Sailors). The

Binder Page ______________ Name _________________________________________________ Period _____________ The War of 1812 Date____________________ PRESIDENT- JAMES MADISON James Madison was known as the “Father of the Constitution” and is sometimes also called the “Father of the Bill of Rights”. He had helped write the Constitution and the Federalist Papers that helped insure that the Constitution would be ratified. However, like his friend Jefferson, he was in the Democratic-Republican party. When Jefferson was President, Madison was his Secretary of State. After Jefferson’s two terms, Madison was elected as our 4th president. By far, the most important thing that happened in his presidency was the War of 1812 . CAUSES OF THE WAR OF 1812 The causes of the War of 1812 are tied to the enormous amount of fighting that had been taking place between Britain and France. The French leader, was trying to take over Europe and Britain was trying to stop him. Americans were making profits trading with both sides. Both Britain and France were forbidding the Americans to trade with the other side. In spite of the fact that the Americans claimed to be neutral, both sides stopped American ships bound for their enemy. Since the British had the stronger navy, they were more effective at stopping American shipping and were seen at the bigger problem. To make matters worse, the British were also forcing British citizens to fight in the their navy. Drafted sailors was a practice known as impressment (or impressing sailors). The British believed that British citizens anywhere in the world could be forced to serve in His Majesty’s Navy. -

The Ambiguous Patriotism of Jack Tar in the American Revolution Paul A

Loyalty and Liberty: The Ambiguous Patriotism of Jack Tar in the American Revolution Paul A. Gilje University of Oklahoma What motivated JackTar in the American Revolution? An examination of American sailors both on ships and as prisoners of war demonstrates that the seamen who served aboard American vessels during the revolution fit neither a romanticized notion of class consciousness nor the ideal of a patriot minute man gone to sea to defend a new nation.' While a sailor could express ideas about liberty and nationalism that matched George Washington and Ben Franklin in zeal and commitment, a mixxture of concerns and loyalties often interceded. For many sailors the issue was seldom simply a question of loyalty and liberty. Some men shifted their position to suit the situation; others ex- pressed a variety of motives almost simultaneously. Sailors could have stronger attachments to shipmates or to a hometown, than to ideas or to a country. They might also have mercenary motives. Most just struggled to survive in a tumultuous age of revolution and change. Jack Tar, it turns out, had his own agenda, which might hold steadfast amid the most turbulent gale, or alter course following the slightest shift of a breeze.2 In tracing the sailor's path in these varying winds we will find that seamen do not quite fit the mold cast by Jesse Lemisch in his path breaking essays on the "inarticulate" Jack Tar in the American Revolution. Lemisch argued that the sailor had a concern for "liberty and right" that led to a "complex aware- ness that certain values larger than himself exist and that he is the victim not only of cruelty and hardship but also, in the light of those values, of injus- tice."3 Instead, we will discover that sailors had much in common with their land based brethren described by the new military historians. -

The War of 1812: the Rise of American Nationalism

University of Washington Tacoma UW Tacoma Digital Commons History Undergraduate Theses History Winter 2016 The aW r of 1812: The Rise of American Nationalism Paul Hanseling [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/history_theses Part of the European History Commons, Military History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hanseling, Paul, "The aW r of 1812: The Rise of American Nationalism" (2016). History Undergraduate Theses. 27. https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/history_theses/27 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UW Tacoma Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of UW Tacoma Digital Commons. The War of 1812: The Rise of American Nationalism A Senior Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Undergraduate History Program of the University of Washington Tacoma By Paul Hanseling University of Washington Tacoma March 2016 Advisor: Dr. Allen 1 Abstract On June 18, 1812, United States President, James Madison, signed a Declaration of War against Great Britain. What brought these two nations to such a dramatic impasse? Madison’s War Message to Congress gives some hint as to the American grievances: impressment of American sailors; unnecessary, “mock” blockades and disruption of American shipping; violations of American neutral rights; and incursions into American coastal waters.1 By far, the most vocal point of contention was impressment, or the forcible enlistment of men in the navy. For their part, Great Britain viewed every measure disputed by Americans as a necessity as they waged war against the Continental advances of Napoleon and for maintaining the economic stability of the British people. -

Open PDF File, 134.33 KB, for Paintings

Massachusetts State House Art and Artifact Collections Paintings SUBJECT ARTIST LOCATION ~A John G. B. Adams Darius Cobb Room 27 Samuel Adams Walter G. Page Governor’s Council Chamber Frank Allen John C. Johansen Floor 3 Corridor Oliver Ames Charles A. Whipple Floor 3 Corridor John Andrew Darius Cobb Governor’s Council Chamber Esther Andrews Jacob Binder Room 189 Edmund Andros Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor John Avery John Sanborn Room 116 ~B Gaspar Bacon Jacob Binder Senate Reading Room Nathaniel Banks Daniel Strain Floor 3 Corridor John L. Bates William W. Churchill Floor 3 Corridor Jonathan Belcher Frederick E. Wallace Floor 2 Corridor Richard Bellingham Agnes E. Fletcher Floor 2 Corridor Josiah Benton Walter G. Page Storage Francis Bernard Giovanni B. Troccoli Floor 2 Corridor Thomas Birmingham George Nick Senate Reading Room George Boutwell Frederic P. Vinton Floor 3 Corridor James Bowdoin Edmund C. Tarbell Floor 3 Corridor John Brackett Walter G. Page Floor 3 Corridor Robert Bradford Elmer W. Greene Floor 3 Corridor Simon Bradstreet Unknown artist Floor 2 Corridor George Briggs Walter M. Brackett Floor 3 Corridor Massachusetts State House Art Collection: Inventory of Paintings by Subject John Brooks Jacob Wagner Floor 3 Corridor William M. Bulger Warren and Lucia Prosperi Senate Reading Room Alexander Bullock Horace R. Burdick Floor 3 Corridor Anson Burlingame Unknown artist Room 272 William Burnet John Watson Floor 2 Corridor Benjamin F. Butler Walter Gilman Page Floor 3 Corridor ~C Argeo Paul Cellucci Ronald Sherr Lt. Governor’s Office Henry Childs Moses Wight Room 373 William Claflin James Harvey Young Floor 3 Corridor John Clifford Benoni Irwin Floor 3 Corridor David Cobb Edgar Parker Room 222 Charles C. -

Who Was Jack Tar?: Aspects of the Social History of Boston, Massachusetts Seamen, 1700-1770

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1972 Who Was Jack Tar?: Aspects of the Social History of Boston, Massachusetts Seamen, 1700-1770 Clark Joseph Strickland College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Strickland, Clark Joseph, "Who Was Jack Tar?: Aspects of the Social History of Boston, Massachusetts Seamen, 1700-1770" (1972). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624780. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-v75p-nz66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO WAS JACK TAR? ASPECTS OF THE SOCIAL HISTORY OF BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS SEAMEN, 1700 - 1770 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Clark J. Strickland 1972 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of f.hoV*A W *Y»onn ViA 1 AT*omon WAMVA* +*VW <s f* AyV A +•V A4VIac» V4 ^ OW f Master of Arts Clark J, Strickland Author Approved, July 1972 Richard Maxwell Brown PhilipsJ U Funigiello J oj Se ii 5 8 5 2 7 3 Cojk TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT........................................... iv CHAPTER I. -

The Province House and Its Occupants

The Province House and its Occupants By WALTER KENDALL WATKINS Edited by RICHARD M. CANDEE HE way to Roxbury, as Wash- by the familial greetings of a letter from ington Street was called in the Sergeant to “Bro. Corwin, Bro. Jona- T first century of Boston’s history, than and Bro. Browne” for John and was bordered north of West Street by the Jonathan Corwin and William Browne homes of some of the principal settlers. who married their sister Hannah Corwin. South of the Town House (the Old State Samuel Sewall noted in his Diary for House) was the South End of the town December 23, 1681 “two of the chief during these years, while the land behind Gentlewomen in Towne dyed, . viz. the Old South Meeting House remained Mrs. Mary Davis and Mrs. Eliza. Sar- pasture for a century more. The west gent (sic) .“* His second marriage, in side of Washington Street was an excel- 1682, was to Elizabeth, daughter of lent location for a house on the main Henry Shrimpton. street, with a fine prospect of the harbor In 1690 the deacons of the Old South and its islands. Church met at Judge Sewall’s house to The first great Boston fire destroyed arrange for documents and deedsrelating these homes on January 14, 1653, to the church to be placed in a chest and among them that of William Aspinwall, depositedin Mr. Sergeant’s house “it be- town recorder, which stood near the ing of brick and convenient.” Sewall present junction of Washington and also notes, after a hailstorm of April 20, Bromfield Streets.