Download (4MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fourteenth Colony: Florida and the American Revolution in the South

THE FOURTEENTH COLONY: FLORIDA AND THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION IN THE SOUTH By ROGER C. SMITH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Roger C. Smith 2 To my mother, who generated my fascination for all things historical 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Jon Sensbach and Jessica Harland-Jacobs for their patience and edification throughout the entire writing process. I would also like to thank Ida Altman, Jack Davis, and Richmond Brown for holding my feet to the path and making me a better historian. I owe a special debt to Jim Cusack, John Nemmers, and the rest of the staff at the P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History and Special Collections at the University of Florida for introducing me to this topic and allowing me the freedom to haunt their facilities and guide me through so many stages of my research. I would be sorely remiss if I did not thank Steve Noll for his efforts in promoting the University of Florida’s history honors program, Phi Alpha Theta; without which I may never have met Jim Cusick. Most recently I have been humbled by the outpouring of appreciation and friendship from the wonderful people of St. Augustine, Florida, particularly the National Association of Colonial Dames, the ladies of the Women’s Exchange, and my colleagues at the St. Augustine Lighthouse and Museum and the First America Foundation, who have all become cherished advocates of this project. -

The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1970 The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740 Ronald P. Dufour College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Dufour, Ronald P., "The Development of Political Theory in Colonial Massachusetts, 1688-1740" (1970). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624699. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ssac-2z49 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEE DEVELOPMENT OF POLITICAL THEORY IN COLONIAL MASSACHUSETTS 1688 - 17^0 A Th.esis Presented to 5he Faculty of the Department of History 5he College of William and Mary in Virginia In I&rtial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Ronald P. Dufour 1970 ProQ uest Number: 10625131 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10625131 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. -

'Deprived of Their Liberty'

'DEPRIVED OF THEIR LIBERTY': ENEMY PRISONERS AND THE CULTURE OF WAR IN REVOLUTIONARY AMERICA, 1775-1783 by Trenton Cole Jones A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland June, 2014 © 2014 Trenton Cole Jones All Rights Reserved Abstract Deprived of Their Liberty explores Americans' changing conceptions of legitimate wartime violence by analyzing how the revolutionaries treated their captured enemies, and by asking what their treatment can tell us about the American Revolution more broadly. I suggest that at the commencement of conflict, the revolutionary leadership sought to contain the violence of war according to the prevailing customs of warfare in Europe. These rules of war—or to phrase it differently, the cultural norms of war— emphasized restricting the violence of war to the battlefield and treating enemy prisoners humanely. Only six years later, however, captured British soldiers and seamen, as well as civilian loyalists, languished on board noisome prison ships in Massachusetts and New York, in the lead mines of Connecticut, the jails of Pennsylvania, and the camps of Virginia and Maryland, where they were deprived of their liberty and often their lives by the very government purporting to defend those inalienable rights. My dissertation explores this curious, and heretofore largely unrecognized, transformation in the revolutionaries' conduct of war by looking at the experience of captivity in American hands. Throughout the dissertation, I suggest three principal factors to account for the escalation of violence during the war. From the onset of hostilities, the revolutionaries encountered an obstinate enemy that denied them the status of legitimate combatants, labeling them as rebels and traitors. -

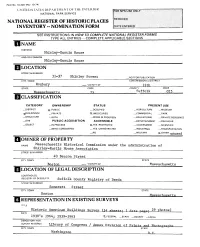

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THh INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC ShirleyrEustis Rouse AND/OR COMMON Shirley'-Eustis House LOCATION STREETS NUMBER 31^37 Shirley Street -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Roxbury _ VICINITY OF 12th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 9^ Suffolk 025 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT ^PUBLIC —OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM -^BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X-YES. RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY x-OTHER unused OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Massachusetts Historical Commission under the administration of ShirleyrEustis Eouse Association_________________________ STREETS NUMBER 4Q Beacon Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Somerset Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston Mas s achtis e t t s REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (14 sheets. 1 29 photos) DATE 1930 f-s 1964. 1939^1963 FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress / Annex Division of Prints and CITY. TOWN STATE Washington n.r DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE .EXCELLENT ^DETERIORATED —UNALTERED __ORIGINALSITE _GOOD _RUINS ^ALTERED DATE. -FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The house, constructed from 1741 to 1756 for Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts became somewhat of a colonial showplace with its imposing facades and elaborate interior designs. -

Historical Study Guide

Historical Study Guide Light A Candle Films presents “THE BATTLE OF BUNKER HILL” Historical Study Guide written by Tony Malanowski To be used with the DVD production of THE BATTLE OF BUNKER HILL The Battle of Bunker Hill Historical Study Guide First, screen the 60-minute DocuDrama of THE BATTLE OF BUNKER HILL, and the 30 minute Historical Perspective. Then, have your Discussion Leader read through the following historical points and share your ideas about the people, the timeframe and the British and Colonial strategies! “Stand firm in your Faith, men of New England” “The fate of unborn millions will now depend, under God, on the courage and conduct of this army. Our cruel and unrelenting enemy leaves us only the choice of brave resistance, or the most abject submission. We have, therefore, to resolve to conquer or die.” - George Washington, August 27, 1776 When General Thomas Gage, the British military governor of Boston, sent one thousand troops to arrest Samuel Adams and John Hancock at Lexington in April of 1775, he could not know the serious implications of his actions. Nor could he know how he had helped to set in motion a major rebellion that would shake the very foundations of the mightiest Empire on earth. General Gage was a military man who had been in North America since the 1750s, and had more experience than any other senior British officer. He had fought in the French and Indian War alongside a young George Washington, with whom he still had a friendly relationship. Gage had married an American woman from a prominent New Jersey family, and 10 of their 11 children had been born in the Colonies. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1950, Volume 45, Issue No. 1

MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE -. % * ,#^iPB P^jJl ?3 ^I^PQPQI H^^yjUl^^ ^_Z ^_^^.: •.. : ^ t lj^^|j|| tm *• Perry Hall, Baltimore County, Home of Harry Dorsey Gough Central Part Built 1773, Wings Added 1784 MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY BALTIMORE larch - 1950 Jft •X'-Jr t^r Jfr Jr J* A* JU J* Jj* Jl» J* Jt* ^tuiy <j» J» Jf A ^ J^ ^ A ^ A •jr J» J* *U J^ ^t* J*-JU'^ Jfr J^ J* »jnjr «jr Jujr «V Jp J(r Jfr Jr Jfr J* «jr»t JUST PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY HISTORY OF QUEEN ANNE'S COUNTY, MARYLAND By FREDERIC EMORY First printed in 1886-87 in the columns of the Centre- ville Observer, this authoritative history of one of the oldest counties on the Eastern Shore, has now been issued in book form. It has been carefully indexed and edited. 629 pages. Cloth binding. $7.50 per copy. By mail $7.75. Published with the assistance of the Queen Anne's County Free Library by the MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY 201 W. MONUMENT STREET BALTIMORE 1 •*••*••*•+•(•'t'+'t-T',trTTrTTTr"r'PTTTTTTTTTTrrT,f'»-,f*"r-f'J-TTT-ft-4"t"t"t"t--t-l- CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING Dftrkxr-BTKrTVTMn FRANK W. LINNEMANN BOOKBINDING 2^ Park Ave Magazines, medical books. Old books rebound PHOTOGRAPHY THE "^^^^ 213 West Monument Street, Baltimore nvr^m^xm > m» • ^•» -, _., ..-•-... „ Baltimore Photo & Blue Print Co PHOTOSTATS & BLUEPRINTS 211 East Baltimore St. Photo copying of old records, genealogical charts LE 688I and family papers. Enlargements. Coats of Arms. PLUMBING — HEATING M. NELSON BARNES Established 1909 BE. -

The Newspapers of the British Empire As a Matrix for The

Warner.communicating.liberty-1 Communicating Liberty: the Newspapers of the British Empire as a Matrix for the American Revolution William B. Warner “I beg your lordship’s permission to observe, and I do it with great concern, that this spirit of opposition to taxation and its consequences is so violent and so universal throughout America that I am apprehensive it will not be soon or easily appeased. The general voice speaks discontent… determined to stop all exports to and imports from Great Britain and even to silence the courts of law…foreseeing but regardless of the ruin that must attend themselves in that case, content to change a comfortable, for a parsimonious life,…” Lieutenant-Governor of South Carolina, Wm. Bull to Earl of Dartmouth, July 31, 1774. [Documents of the American Revolution, 1770-1783, Ed. K. G. Davies. (Dublin: Irish University Press, 1975) VIII: 1774, 154.] Momentous historical events often issue from a nexus of violence and communication. While American independence from Britain ultimately depended upon the spilling of blood on the battlefields of Bunker Hill, Saratoga and Yorktown, the successful challenge to the legitimacy of British rule in America was the culmination of an earlier communications war waged by American Whigs between the Stamp Act agitation of 1764-5 and the Coercive Acts of 1774. In response to the first of the Coercive acts--the Boston Port Bill--Boston Whigs secured a tidal wave of political and material support from throughout the colonies of British America. By the end of 1774, the American Secretary at Whitehall, Lord Dartmouth, was receiving reports from colonial Governors of North America, like the passage quoted above from the Lieutenant-Governor of South Caroline, William Bull. -

Ocm01251790-1863.Pdf (10.24Mb)

u ^- ^ " ±i t I c Hon. JONATHAN E. FIELD, President. 1. —George Dwight. IJ. — K. M. Mason. 1. — Francis Briwiej'. ll.-S. .1. Beal. 2.— George A. Shaw. .12 — Israel W. Andrews. 2.—Thomas Wright. 12.-J. C. Allen. 3. — W. F. Johnson. i'i. — Mellen Chamberlain 3.—H. P. Wakefield. 13.—Nathan Crocker. i.—J. E. Crane. J 4.—Thomas Rice, .Ir. 4.—G. H. Gilbert. 14.—F. M. Johnson. 5.—J. H. Mitchell. 15.—William L. Slade. 5. —Hartley Williams. 15—H. M. Richards. 6.—J. C. Tucker. 16. —Asher Joslin. 6.—M. B. Whitney. 16.—Hosea Crane. " 7. —Benjamin Dean. 17.— Albert Nichols. 7.—E. O. Haven. 17.—Otis Gary. 8.—William D. Swan. 18.—Peter Harvey. 8.—William R. Hill. 18.—George Whitney. 9.—.]. I. Baker. 19.—Hen^^' Carter. 9.—R. H. Libby. 19.—Robert Crawford. ]0.—E. F. Jeiiki*. 10.-—Joseph Breck. 20. —Samuel A. Brown. .JOHN MORIS?5KV, Sevii^aiU-ut-Anns. S. N. GIFFORU, aerk. Wigatorn gaHei-y ^ P=l F ISSu/faT-fii Lit Coiranoittoralllj of llitss3t|ttsttts. MANUAL FOR THE USE OF THE G-ENERAL COURT: CONTAINING THE RULES AND ORDERS OF THE TWO BRANCHES, TOGETHER WITH THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH, AND THAT OF THE UNITED STATES, A LIST OF THE EXECUTIVE, LEGISLATIVE, AND JUDICIAL DEPARTMENTS OF THE STATE GOVERNMENT, STATE INSTITUTIONS AND THEIR OFFICERS, COUNTY OFFICERS, AND OTHER STATISTICAL INFORMATION. Prepared, pursuant to Orders of the Legislature, BY S. N. GIFFORD and WM. S. ROBINSON. BOSTON: \yRIGHT & POTTER, STATE PRINTERS, No. 4 Spring Lane. 1863. CTommonbtaltfj of iBnssacf)useits. -

Lexington and Concord

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Lexington and Concord: A Legacy of Conflict Minute Man National Historical Park On April 19, 1775 ten years of political protest escalated as British soldiers clashed with “minute men” at Lexington, Concord, and along the a twenty-two- mile stretch of road that ran from Boston to Concord. The events that occurred along the Battle Road profoundly impacted the people of Massachusetts and soon grew into an American war for independence and self-government. This curriculum–based lesson plan is one Included in this lesson are several pages of in a thematic set on the American supporting material. To help identify these Revolution using lessons from other pages the following icons may be used: Massachusetts National Parks. Also are: To indicate a Primary Source page Boston National Historical Park To indicate a Secondary Source page To Indicate a Student handout Adams National Historical Park To indicate a Teacher resource Lesson Document Link on the page to the Salem Maritime National Historic Site document Lexington and Concord: A Legacy of Conflict Page 1 of 19 Minute Man National Historical Park National Park Service Minuteman National Historical Park commemorates the opening battles of the American Revolution on April 19, 1775. What had begun ten years earlier as political protest escalated as British soldiers clashed with colonial militia and “minute men” in a series of skirmishes at Lexington, Concord, and along the a twenty-two-mile stretch of road that ran from Boston to Concord. The events that occurred along the Battle Road profoundly impacted the people of Massachusetts and soon grew into an American war for independence and self-government. -

PELLIZZARI-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (3.679Mb)

A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Pellizzari, Peter. 2020. A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37365752 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778 A dissertation presented by Peter Pellizzari to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2020 © 2020 Peter Pellizzari All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisors: Jane Kamensky and Jill Lepore Peter Pellizzari A Struggle for Empire: Resistance and Reform in the British Atlantic World, 1760-1778 Abstract The American Revolution not only marked the end of Britain’s control over thirteen rebellious colonies, but also the beginning of a division among subsequent historians that has long shaped our understanding of British America. Some historians have emphasized a continental approach and believe research should look west, toward the people that inhabited places outside the traditional “thirteen colonies” that would become the United States, such as the Gulf Coast or the Great Lakes region. -

Chronology of the American Revolution

INTRODUCTION One of the missions of The Friends of Valley Forge Park is the promotion of our historical heritage so that the spirit of what took place over two hundred years ago continues to inspire both current and future generations of all people. It is with great pleasure and satisfaction that we are able to offer to the public this chronology of events of The American Revolution. While a simple listing of facts, it is the hope that it will instill in some the desire to dig a little deeper into the fascinating stories underlying the events presented. The following pages were compiled over a three year period with text taken from many sources, including the internet, reference books, tapes and many other available resources. A bibliography of source material is listed at the end of the book. This publication is the result of the dedication, time and effort of Mr. Frank Resavy, a long time volunteer at Valley Forge National Historical Park and a member of The Friends of Valley Forge Park. As with most efforts of this magnitude, a little help from friends is invaluable. Frank and The Friends are enormously grateful for the generous support that he received from the staff and volunteers at Valley Forge National Park as well as the education committee of The Friends of Valley Forge Park. Don R Naimoli Chairman The Friends of Valley Forge Park ************** The Friends of Valley Forge Park, through and with its members, seeks to: Preserve…the past Conserve…for the future Enjoy…today Please join with us and help share in the stewardship of Valley Forge National Park. -

What Actually Happened on the Midnight Ride?

Revere House Radio Episode 4 Revisit the Ride: What Actually Happened on the Midnight Ride? Welcome in to another episode of Revere House Radio, Midnight Ride Edition. I am your host Robert Shimp, and we appreciate you listening in as we continue to investigate different facets of Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride leading up to Patriots Day in Boston on Monday April 20. Today, April 18, we will commemorate Paul Revere’s ride, which happened 245 years ago today, by answering the question of what actually happened that night? Previously, we have discussed the fact that he was a known and trusted rider for the Sons of Liberty, and that he did not shout “The British Are Coming!” along his route, but rather stopped at houses along the way and said something to the effect of: “the regulars are coming out.” With these points established, we can get into the nuts and bolts of the evening- how did the night unfold for Paul Revere? As we discussed on Thursday, Paul Revere and Dr. Joseph Warren had known for some time that a major action from the British regulars was in the offing at some point in April 1775- and on April 18, Revere and Warren’s surveillance system of the British regulars paid off. Knowing an action was imminent, Warren called Revere to his house that night to give him his orders- which in Paul Revere’s recollections- were to alert John Hancock and Samuel Adams that the soldiers would be marching to the Lexington area in a likely attempt to seize them.