An Investment Guide to Cambodia: Opportunities and Conditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Etiquette, Language & Culture

Business etiquette, language & culture Page 1 of 5 Business etiquette, language & culture Overview Khmer is the official language of Cambodia and is used by roughly 90% of the population. Due to the past colonial rule by France, a number of French words exist in the language. However, English is not widely understood, particularly amongst the older generation and in rural areas. Business cards should be translated into Cambodian and printed in English on one side and Cambodian on the other. Use the services of a professional translator (rather than translating online) – a list of translators and interpreters has been prepared by the British Embassy Phnom Penh for the convenience of British Nationals who may require these services and assistance in Cambodia, at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cambodia-list-of-translators-and- interpreters. As in China, business cards should be given and received with both hands and studied carefully. This is particularly important when dealing with Cambodia’s ethnic Chinese minority, many of whom hold influential positions in the country’s business community. The Cambodian culture is conservative and hierarchical, and Theravada Buddhism is practiced by 95% of the population. Followers adhere to the concept of collectivism – the idea that the family, neighbourhood and society is more important than the wishes of the individual – and as in many Asian cultures the sense of ‘face’ is also considered paramount. Consequently you should avoid causing public embarrassment, not lose your temper in public and strive to maintain a sense of harmony. As a sign of respect for western customs, handshakes are the norm between men, but it is not uncommon to greet women with the “Sampeah” – the placing of palms together in a prayer-like position at chest level, with a slight bow of the head. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Singapore Airlines 2001 (A)

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Singapore Airlines 2001 (A) Allampalli, D. G.; Toh, Thian Ser 2001 Toh, T. S., & Allampalli, D. G. (2001). Singapore Airlines 2001 (A). Singapore: The Asian Business Case Centre, Nanyang Technological University. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/100011 © 2001 Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, stored, transmitted, altered, reproduced or distributed in any form or medium whatsoever without the written consent of Nanyang Technological University. Downloaded on 24 Sep 2021 00:44:01 SGT AsiaCase.com the Asian Business Case Centre SINGAPORE AIRLINES 2001 (A) Publication No: ABCC-2001-004A Print copy version: 15 Apr 2004 Toh Thian Ser and D. G. Allampalli The case describes how Singapore Airlines (SIA) evolved from a fl edging player in the 1960s into an industry leader. In the process, SIA rewrote the rules for competition and earned accolades for its excellent aviation record, young fl eet of planes and a reputation for delighting customers. Bilateral air service agreements negotiated between individual nations limited the routes of a given airlines and hence the airlines’s growth. The global airlines industry responded to this challenge with a mix of acquisition, strategic alliances (for example, the STAR alliance) and related diversifi cation strategies. But would these strategies be sustainable in the near future for SIA? What course of action should SIA undertake? Associate Professor Toh Thian Ser and D. G. Allampalli of The Asian Business Case Centre prepared this case. The case is based on public sources. -

The Continuing Presence of Victims of the Khmer Rouge Regime in Today's

Powerful remains: the continuing presence of victims of the Khmer Rouge regime in today’s Cambodia HUMAN REMAINS & VIOLENCE Helen Jarvis Permanent People’s Tribunal, UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme [email protected] Abstract The Khmer Rouge forbade the conduct of any funeral rites at the time of the death of the estimated two million people who perished during their rule (1975–79). Since then, however, memorials have been erected and commemorative cere monies performed, both public and private, especially at former execution sites, known widely as ‘the killing fields’. The physical remains themselves, as well as images of skulls and the haunting photographs of prisoners destined for execution, have come to serve as iconic representations of that tragic period in Cambodian history and have been deployed in contested interpretations of the regime and its overthrow. Key words: Cambodia, Khmer Rouge, memorialisation, Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, dark tourism Introduction A photograph of a human skull, or of hundreds of skulls reverently arranged in a memorial, has become the iconic representation of Cambodia. Since the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge regime on 7 January 1979, book covers, film posters, tourist brochures, maps and sign boards, as well as numerous original works of art, have featured such images of the remains of its victims, often coupled with the haunting term ‘the killing fields’, as well as ‘mug shots’ of prisoners destined for execution. Early examples on book covers include the first edition of Ben Kiernan’s seminal work How Pol Pot Came to Power, published in 1985, on which the map of Cambodia morphs into the shape of a human skull and Cambodia 1975–1978: Rendezvous with Death, edited by Karl D. -

Three Years Projects Report (From April 2014 to September 2016)

Three Years Projects Report (From April 2014 to September 2016) 1. Community Childcare Project 1-1. Project Location a. Beung Kyang Childcare Center in Beung Kyang Village, Prey Tatoch Childcare Center in Prey Tatoach Village, Beung Kyang Commune, Kandal Steung District, Kandal Province b. Government Pre-schools in Uddar Meanchey province c. Twelve childcare centers in Khan Russey Keo, Khan Sen Sok, Khan Prek Phnov, and Khan Chroy Chanva, Phnom Penh and Ksach Kandal district, Kandal province d. Trapaing Svay Primary School, Sangkat Phnom Penh Thmey, Khan Sen Sok,, Phnom Penh e. Two community pre-schools, one in Prasat village, Prek Sleng commune and another in Ta Prom village, Beung Kyang commune, Kandal Steung district, Kandal province f. Three village pre-schools in Lompong commune, Bati district, Takeo province g. Government community pre-schools in 25 municipality-provinces which were opened from 2014 h. Three village pre-schools in Kaom Samnor commune, Leuk Dek district and one in Prey Pouch commune, Ang Snuol district, Kandal province i. One village pre-school in Sdao Kanlaeng 5 village, Dei Eth commune, Kien Svay district, Kandal province j. Two village pre-schools in Svay Damnak village, Svay Romeat commune, Ksach Kandal district, Kandal province 1-2. Main Goals of The Project - To provide childcare and educational opportunities for young children in order to support their healthy development both physically and mentally. - To promote understanding of the importance of early childhood care and education among childcare teachers, parents and communities. - To train community childcare teachers to acquire appropriate knowledge and skills of childcare. - To support the managing and supporting committee to be self-reliant of managing the childcare centers and village pre-school through capacity building trainings, parental and community collaboration and small-scale credit project. -

Years Years Service Or 20,000 Hours of Flying

VOL. 9 NO. 1 OCTOBER 2001 MAGAZINE OF THE ASSOCIATION OF ASIA PACIFIC AIRLINES 50 50YEARSYEARS Japan Airlines celebrating a golden anniversary AnsettAnsett R.I.PR.I.P.?.? Asia-PacificAsia-Pacific FleetFleet CensusCensus UPDAUPDATETE U.S.U.S. terrterroror attacks:attacks: heavyheavy economiceconomic fall-outfall-out forfor Asia’Asia’ss airlinesairlines VOL. 9 NO. 1 OCTOBER 2001 COVER STORY N E W S Politics still rules at Thai Airways International 8 50 China Airlines clinches historic cross strait deal 8 Court rules 1998 PAL pilots’ strike illegal 8 YEARS Page 24 Singapore Airlines pulls out of Air India bid 10 Air NZ suffers largest corporate loss in New Zealand history 12 Japan Airlines’ Ansett R.I.P.? Is there any way back? 22 golden anniversary Real-time IFE race hots up 32 M A I N S T O R Y VOL. 9 NO. 1 OCTOBER 2001 Heavy economic fall-out for Asian carriers after U.S. terror attacks 16 MAGAZINE OF THE ASSOCIATION OF ASIA PACIFIC AIRLINES HELICOPTERS 50 Flying in the face of bureaucracy 34 50YEARS Japan Airlines celebrating a FEATURE golden anniversary Training Cathay Pacific Airways’ captains of tomorrow 36 Ansett R.I.P.?.? Asia-Pacific Fleet Census UPDATE S P E C I A L R E P O R T Asia-Pacific Fleet Census UPDATE 40 U.S. terror attacks: heavy economic fall-out for Asia’s airlines Photo: Mark Wagner/aviation-images.com C O M M E N T Turbulence by Tom Ballantyne 58 R E G U L A R F E A T U R E S Publisher’s Letter 5 Perspective 6 Business Digest 51 PUBLISHER Wilson Press Ltd Photographers South East Asia Association of Asia Pacific Airlines GPO Box 11435 Hong Kong Andrew Hunt (chief photographer), Tankayhui Media Secretariat Tel: Editorial (852) 2893 3676 Rob Finlayson, Hiro Murai Tan Kay Hui Suite 9.01, 9/F, Tel: (65) 9790 6090 Kompleks Antarabangsa, Fax: Editorial (852) 2892 2846 Design & Production Fax: (65) 299 2262 Jalan Sultan Ismail, E-mail: [email protected] Ü Design + Production Web Site: www.orientaviation.com E-mail: [email protected] 50250 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. -

No. Service Station Time Address 1 TOTAL Avenue De France 24 Hours Corner Street 47-61 & 84 Sangkat Sras Chak Khan Daun Penh

No. Service Station Time Address 1 TOTAL Avenue de France 24 Hours Corner Street 47-61 & 84 Sangkat Sras Chak Khan Daun Penh Phnom Penh 2 TOTAL Chateau d'Eau 05:00-20:00 Street 217+274 Sangkat Veal Vong Khan 7 Makara Phnom Penh 3 TOTAL La deesse 05:00-21:00 St. 182 & 189, Sangkat Veal Vong, Khan 7 Makara, Phnom Penh 4 TOTAL La Gare 05:00-21:00 Between Street 108 & Russian Blvd Sangkat Sras Chak Khan Daun Penh Phnom Penh 5 TOTAL Takhmao 24 Hours National Road N.2, Doem Kor Village, Khum Doem Miem, Kandal Province 6 TOTAL Monivong 24 Hours #370, Corner Street 93 & 310, Sangkat Boeung Keng Kang I, Khan Chamkamon, Phnom Penh 7 TOTAL Pochentong 05:00-22:00 Russian Blvd Phum Tek Thla Sangkat Tek Thla Khan Sen Sok Phnom Penh 8 TOTAL Marche Central (Phsa Thmey) 05:00-21:00 #602 Street Charles de Gaulle Sangkat Psar Thmei 2 Khan Daun Penh Phnom Penh 9 TOTAL Prek Leap (6A4) 05:00-22:00 Plot#126, road 6A, Phum Keanklaing, Sangkat Prek Leap, Khan Russey Keo, PP. 10 TOTAL Russey Keo 05:00-22:00 National road No5, Phum Boeng Chhouk, Sangkat Km6, Khan Russey Keo,PP. 11 TOTAL Century 24 Hours Russian Blvd, Sangkat Kakap, Khan Dankor,PP. 12 TOTAL Odem 05:00-22:00 NR4, Odem Village, Sangkat Chaom Chao, Khan Porsenchey, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. 13 TOTAL Toul Kok 05:00-22:00 St.289,Sangkat Boeung Kak II, Khan Toul Kok, Phnom Penh , Cambodia. 14 TOTAL Phnom Penh Thmey 05:00-22:00 St.1986 Sangkat Phnom Penh Thmey, Khan Sen Sok, Phnom Penh 15 TOTAL Chroy Changva 05:00-20:00 Phum 3, Sangkat Chroy Changvar, Khan Chroy Changvar , Phnom Penh City 16 TOTAL Chbar Ampov 24 Hours National road No1, Sangkat Chbar Ampov I, Khan Chbar Ampov, Phnom Penh. -

Newcambodia 1 HS

CULTUREGUIDE CAMBODIA SERIES 1 SECONDARY (7–12) Photo by Florian Hahn on Unsplash CAMBODIA CULTUREGUIDE This unit is published by the International Outreach Program of the David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies at Brigham Young University as part of an effort to foster open cultural exchange within the educational community and to promote increased global understanding by providing meaningful cultural education tools. Curriculum Development Richard Gilbert has studied the Cambodian language and culture since 1997. For two years, he lived among the Cambodian population in Oakland, California. He was later priv- ileged to work in Cambodia during the summer of 2001 as an intern for the U.S. Embassy. He is fluent in Cambodian and is a certified Cambodian language interpreter. Editorial Staff Content Review Committee Victoria Blanchard, CultureGuide publica- Jeff Ringer, director tions coordinator International Outreach Cory Leonard, assistant director Leticia Adams David M. Kennedy Center Adrianne Gardner Ana Loso, program coordinator Anvi Hoang International Outreach Anne Lowman Sopha Ly, area specialist Kimberly Miller Rebecca Thomas Special Thanks To: Julie Volmar Bradley Bessire, photographer Audrey Weight Kirsten Bodensteiner, photographer Andrew Gilbert, photographer J. Lee Simons, editor Brett Gilbert, photographer Kennedy Center Publications Ian Lowman, photographer: Monks and New Age Shaman in Phnom Penh, Coconut Vender in Phnom Penh, Pediment on Eleventh Century Buddhist Temple, and Endangered Wat Nokor in Kâmpóng Cham For more information on the International Outreach program at Brigham Young University, contact International Outreach, 273 Herald R. Clark Building, PO Box 24537, Provo, UT 84604- 9951, (801) 422-3040, [email protected]. © 2004 International Outreach, David M. -

Investment in Air Transport Infrastructure

Guidance for developing private participation Infrastructure Transport Air Investment in Public Disclosure Authorized Investment in Air Transport Infrastructure Guidance for developing Public Disclosure Authorized private participation Mustafa Zakir Hussain, Editor With case studies prepared by Booz Allen Hamilton Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Investment in Air Transport Infrastructure Guidance for developing private participation Investment in Air Transport Infrastructure Guidance for developing private participation Mustafa Zakir Hussain, Editor With case studies prepared by Booz Allen Hamilton © 2010 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Direc- tors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorse- ment or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of appli- cable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. -

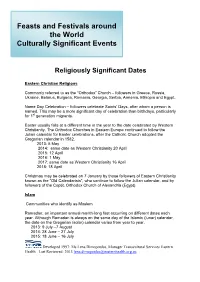

Feasts and Festivals Around the World Culturally Significant Events

Feasts and Festivals around the World Culturally Significant Events Religiously Significant Dates Eastern Christian Religions Commonly referred to as the “Orthodox” Church – followers in Greece, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Bulgaria, Romania, Georgia, Serbia, Armenia, Ethiopia and Egypt. Name Day Celebration – followers celebrate Saints’ Days, after whom a person is named. This may be a more significant day of celebration than birthdays, particularly for 1st generation migrants. Easter usually falls at a different time in the year to the date celebrated by Western Christianity. The Orthodox Churches in Eastern Europe continued to follow the Julian calendar for Easter celebrations, after the Catholic Church adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1582. 2013: 5 May 2014: same date as Western Christianity 20 April 2015: 12 April 2016: 1 May 2017: same date as Western Christianity 16 April 2018: 18 April Christmas may be celebrated on 7 January by those followers of Eastern Christianity known as the “Old Calendarists”, who continue to follow the Julian calendar, and by followers of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria (Egypt). Islam Communities who identify as Moslem Ramadan: an important annual month-long fast occurring on different dates each year. Although Ramadan is always on the same day of the Islamic (lunar) calendar, the date on the Gregorian (solar) calendar varies from year to year. 2013: 9 July –7 August 2014: 28 June – 27 July 2015: 18 June – 16 July Developed 1997: Ms Lena Dimopoulos, Manager Transcultural Services Eastern Health Last Reviewed: 2013 [email protected] 2016: 6 June – 5 July 2017: 27 May – 25 July 2018: 16 May – 14 June New Year: some Moslems may fast during daylight hours. -

LEAP) (P153591) Public Disclosure Authorized

SFG2503 REV KINGDOM OF CAMBODIA Livelihood Enhancement and Association of the Poor Public Disclosure Authorized (LEAP) (P153591) Public Disclosure Authorized Resettlement Policy Framework (RPF) November 14, 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized LEAP P153591 – Resettlement Policy Framework, November 14, 2016 Livelihood Enhancement and Association of the Poor (LEAP) (P153591) TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE OF CONTENT ............................................................................................................................... i LIST OF ACRONYMS .............................................................................................................................. iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... v 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1. Background .............................................................................................................................. 1 1.2. Social Analysis ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.3. Requirements for RPF and Purpose ......................................................................................... 2 2. PROJECT DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVE AND PROJECT DESCRIPTION........................ 3 2.1. Project Development Objective .............................................................................................. -

Change 3, FAA Order 7340.2A Contractions

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION 7340.2A CHG 3 SUBJ: CONTRACTIONS 1. PURPOSE. This change transmits revised pages to Order JO 7340.2A, Contractions. 2. DISTRIBUTION. This change is distributed to select offices in Washington and regional headquarters, the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center; to all air traffic field offices and field facilities; to all airway facilities field offices; to all international aviation field offices, airport district offices, and flight standards district offices; and to the interested aviation public. 3. EFFECTIVE DATE. July 29, 2010. 4. EXPLANATION OF CHANGES. Changes, additions, and modifications (CAM) are listed in the CAM section of this change. Changes within sections are indicated by a vertical bar. 5. DISPOSITION OF TRANSMITTAL. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. PAGE CONTROL CHART. See the page control chart attachment. Y[fa\.Uj-Koef p^/2, Nancy B. Kalinowski Vice President, System Operations Services Air Traffic Organization Date: k/^///V/<+///0 Distribution: ZAT-734, ZAT-464 Initiated by: AJR-0 Vice President, System Operations Services 7/29/10 JO 7340.2A CHG 3 PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−2 . 4/8/10 CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−2 . 7/29/10 1−1−1 . 8/27/09 1−1−1 . 7/29/10 2−1−23 through 2−1−27 . 4/8/10 2−1−23 through 2−1−27 . 7/29/10 2−2−28 . 4/8/10 2−2−28 . 4/8/10 2−2−23 .