Executive Summary DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY for CLMV in THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pro-Poor Tourism Thailand in the Greatergreater Mmekongekong Sub-Regionsub-Region

CAMBODIACAMBODIA CambodiaCambodia DevelopmentDevelopment Resource InstituteInstitute (CDRI)(CDRI) LAOSLAOS PRO-POOR TOURISM THAILAND IN THE GREATERGREATER MMEKONGEKONG SUSUB-REGIONB-REGION DevelopmentDevelopment Analysis Network (DAN) with Support fromfrom the RockefellerRockefeller Foundation CambodiaCambodia DevelopmentDevelopment Resource Institute (CDRI), Phnom PenhPenh VIETNAMVIETNAM CCentreentre fforor Advanced StudStudyy (CAS), Phnom PenPenhh NationaNationall Statistics Centre (NSC)(NSC),, Vientiane National Economic Research Institute (NERI), VientianVientianee Thailand Development Resource Institute (TDRI), BanBangkokgkok CCentralentral Institute for Economic ManaManagementgement (CIEM), HanoHanoii Institute ooff Economics, HanoHanoii CCentreentre fforor Community Development Studies, KunminKunming,g, YunnaYunnann Yunnan-CHINAYunnan-CHINA3 2 Cambodia Development Resource Institute (CDRI) Phnom Penh, July 2007 PRO-POOR TOURISM IN THE GREATER MEKONG SUB-REGION 1 © 2007 Development Analysis Network All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the written permission of the Development Analysis Network and its member institutions. The designations employed in Development Analysis Network publications and the presentation of material contained therein do not imply any expression whatsoever on the part of the Development Analysis Network or its member institutions concerning -

Featured Tour Cambodia

September 2007 Welcome… A very warm welcome to the latest issue of Som Leng for 2007 from all the team at Hanuman Tourism. This has been a very busy year for us, as tourism numbers continue to soar in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. The upside of this has been new product, new hotels and new members of our team. The downside is higher prices for some hotels and a real squeeze on room availability during the peak season. However, here at Hanuman we remain committed to bringing you the best experiences at the best possible rates. As we move into the second half of the year, we are looking at developing a new, improved Temple Safari experience and will be restructuring all our existing itineraries to ensure we continue to have the best product available in the Mekong region. We will significantly expand our itineraries in Laos to reflect the success of our office there and will be overhauling Vietnam as we move towards an office opening in 2008. That's all for now. We look forward to a successful high season for 2007-08 and will continue to provide you with the quality service for which we are renowned. Truly travel with a personal touch. Kulikar Sotho Chief Executive Featured Tour Beach Safari Imagine your own private beach on the incredible tropical islands off the coast of Cambodia... On the secluded islands of Cambodia you will feel like a true castaway as you camp on deserted beaches and feast on freshly caught fish cooked over a fire. Cambodia's islands are slated for development, so seize the moment to take a beach safari to one of the remote islands off Sihanoukville or Kep before these paradises disappear forever. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

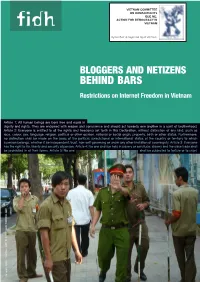

Bloggers and Netizens Behind Bars: Restrictions on Internet Freedom In

VIETNAM COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RIGHTS QUÊ ME: ACTION FOR DEMOCRACY IN VIETNAM Ủy ban Bảo vệ Quyền làm Người Việt Nam BLOGGERS AND NETIZENS BEHIND BARS Restrictions on Internet Freedom in Vietnam Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, January 2013 / n°603a - AFP PHOTO IAN TIMBERLAKE Cover Photo : A policeman, flanked by local militia members, tries to stop a foreign journalist from taking photos outside the Ho Chi Minh City People’s Court during the trial of a blogger in August 2011 (AFP, Photo Ian Timberlake). 2 / Titre du rapport – FIDH Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------5 -

(Iipa) 2019 Special 301 Report on Copyright Protection and Enforcement

INTERNATIONAL INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ALLIANCE (IIPA) 2019 SPECIAL 301 REPORT ON COPYRIGHT PROTECTION AND ENFORCEMENT Special 301 Recommendation: IIPA recommends that Vietnam should be elevated to the Priority Watch List in 2019.1 Executive Summary: Vietnam is an important emerging market in Southeast Asia for the creative industries, which has investments planned to tap into Vietnam’s booming economy. But the market for creative works in Vietnam remains severely stunted due to worsening piracy and persistent and debilitating market access barriers. Vietnam is now host to many of the world’s most popular piracy websites, and other problems are growing, including Piracy Devices and apps used to access illegal content. While rights holders have implored Vietnam’s government to take action, the government has done very little to address the growing problem. For example, while the highly popular online piracy site 123movies was shut down due to considerable pressure from the U.S. Government and from industry, the Government of Vietnam did not take any effective actions against those responsible for the site. Thus, the site appears to have simply sold its main architecture, which has led to a proliferation of copycat sites around the world. One exception is the government’s support for national broadcasters to protect their investment in the World Cup broadcast by disabling access to hundreds of infringing websites. Unfortunately, the government has not been as amenable to working with foreign rights holders to take action against similarly harmful websites hosting or distributing other types of infringing content. Rights holders face unreasonable hurdles in enforcing their rights, including requirements for evidence collection that are impossible to meet. -

2. the Link Between Child Sex Tourism and Child Trafficking

Foreword International child sex tourism, a truly global phenomenon, and one which affects some of the most vulnerable members of our societies – children and adolescents, has received significantly less attention on the international arena than have other related phenomena, such as child pornography and trafficking in children for commercial sexual exploitation. While these crimes are all closely linked, and demand concerted action, child sex tourism deserves significantly more attention than it has been receiving as a stand-alone concern. In this regard, the United States Department of State Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (TIP Office) has taken the lead in placing emphasis on child sex tourism as an issue that deserves improved understanding and greater levels of intervention. Child sex tourism is mentioned in numerous country narratives in the 2006 Trafficking in Persons Report, and the TIP Office is clearly committed to including countries’ efforts to combat child sex tourism, especially as connected to the creation of demand for child sex tourism, in its consideration for tier placements. The report, based on exhaustive research conducted by The Protection Project (TPP) regarding the issue of child sex tourism, was made possible by a generous award from the TIP Office seeking to improve understanding of the global phenomenon of international child sex tourism and existing interventions to combat it. The report provides a description of the scope of the problem of child sex tourism and illustrates different responses adopted in several countries where child sex tourism is emerging or significant, especially Cambodia, Costa Rica, Honduras, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam. -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

Urban Green Areas – Their Functions Under a Changing Lifestyle of Local People, the Example of Hanoi

Urban Green Areas – their functions under a changing lifestyle of local people, the example of Hanoi Inauguraldissertation Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) an der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-Universität Greifswald vorgelegt von LE To Luong geboren am 18.10.1983 in Ha Noi, Vietnam Greifswald, den 5. Marz 2013 Dekan: Prof. Dr. Klaus Fesser 1. Gutachter : Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Steingrube 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Hai Thi Nguyen Tag der Promotion: 21/06/2013 TABLE OF CONTENT Page Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………… vii List of figures…………………………………………………………………………….. xiii List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………... xvi List of Pictures……………………………………………………………………………. xvii Abbreviations and Equivalents…………………………………………………………. xviii 1 Introduction………………………….…………………………… 1 1.1 Hanoi – the city of investigation…………………………………… 2 1.1.1 Location and topography………………………………………………………. 2 1.1.2 Climate…………………………………………………………………………... 2 1.2 Hanoi – city plans and management ……………………………… 4 1.2.1 Phases of urban planning in Hanoi…………………………………………… 5 1.2.1.1 Hanoi’s plans before 1885………………………………………………………. 5 1.2.1.2 Hanoi’s plans 1885-1945………………………………………………………… 6 1.2.1.3 Period 1954-1964 ……………………………………………………………….. 7 1.2.1.4 Period 1964-1974……..………………………………………………………….. 8 1.2.1.5 Period 1975-1986……………………………………………………………….. 8 1.2.1.6 Period 1998 to date……………………………………………………………… 8 1.2.1.7 The future vision of Hanoi…………………………………………………………12 1.2.2 The political system in Hanoi………….…….…………………………………. 13 1.2.3 Management process of Planning….…………………………………………. 14 1.3 Objectives and hypotheses………………….…………………........ 17 1.4 Methodological Approach………………………………………….. 18 1.4.1 Statistics…………………………………………………………………………. 21 1.4.2 Observation……………………………………………………………………… 21 1.4.3 Visitor counting…………………………………………………………………. 23 1.4.4 Surveys…………………………………………………………………………... 24 1.4.4.1 Online survey……………………………………………………………………. -

Change 3, FAA Order 7340.2A Contractions

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION 7340.2A CHG 3 SUBJ: CONTRACTIONS 1. PURPOSE. This change transmits revised pages to Order JO 7340.2A, Contractions. 2. DISTRIBUTION. This change is distributed to select offices in Washington and regional headquarters, the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center; to all air traffic field offices and field facilities; to all airway facilities field offices; to all international aviation field offices, airport district offices, and flight standards district offices; and to the interested aviation public. 3. EFFECTIVE DATE. July 29, 2010. 4. EXPLANATION OF CHANGES. Changes, additions, and modifications (CAM) are listed in the CAM section of this change. Changes within sections are indicated by a vertical bar. 5. DISPOSITION OF TRANSMITTAL. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. PAGE CONTROL CHART. See the page control chart attachment. Y[fa\.Uj-Koef p^/2, Nancy B. Kalinowski Vice President, System Operations Services Air Traffic Organization Date: k/^///V/<+///0 Distribution: ZAT-734, ZAT-464 Initiated by: AJR-0 Vice President, System Operations Services 7/29/10 JO 7340.2A CHG 3 PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−2 . 4/8/10 CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−2 . 7/29/10 1−1−1 . 8/27/09 1−1−1 . 7/29/10 2−1−23 through 2−1−27 . 4/8/10 2−1−23 through 2−1−27 . 7/29/10 2−2−28 . 4/8/10 2−2−28 . 4/8/10 2−2−23 . -

New Voices: Socio-Cultural Trajectories of Vietnamese Literature in the 21St Century

New Voices: Socio-Cultural Trajectories of Vietnamese Literature in the 21st Century NEW VOICES: SOCIO-CULTURAL TRAJECTORIES OF VIETNAMESE LITERATURE IN THE 21st CENTURY Dana HEALY School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London Thornhaugh Street, Russell Square, WC1H 0XG London, UK [email protected] Many important changes have taken place in the domain of Vietnamese literature in the last two decades as the country embraced the new globalized consumer age. This article examines the ways in which contemporary Vietnamese literature responds to the new social and cultural milieu delineated by rapidly developing market economy, globalization, and rise in new technologies, mass media and the internet. It highlights the role of young generation of writers whose enthusiasm, unorthodox creativity, penchant for experiment and resentment of authority contributed to the transformation of Vietnamese literature from a ‘servant of revolution’ to the purveyor of entertainment, modernity and individualism. It also analyses the changes in the publishing industry and evaluates the role of the internet in Vietnam as a vital alternative space which can accomodate various forms of marginalized writing. Key words: Vietnamese literature, publishing, the internet, popular literature Introduction Contemporary literature in Vietnam derives its momentum from a new generation of writers. With their youthful enthusiasm, unorthodox creativity, penchant for experiment, resentment of authority and desire for freedom they are defying established Vietnamese -

2018Spec301vietnam

VIETNAM INTERNATIONAL INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ALLIANCE (IIPA) 2018 SPECIAL 301 REPORT ON COPYRIGHT PROTECTION AND ENFORCEMENT Special 301 Recommendation: IIPA recommends that Vietnam should be elevated to the Priority Watch List in 2018.1 Executive Summary: As a result of worsening piracy and persistent market access barriers that exacerbate the problem, the market in Vietnam for creative goods and services is severely stunted. While Vietnam’s Government has recently taken certain steps that indicate it is beginning to recognize the seriousness of its growing piracy problem, more substantial actions are needed. Vietnam has committed to ratifying the WIPO Digital Treaties, and, without delay, the government should take the necessary steps to ratify and implement them. It is long past time for Vietnam to make good on its political commitments and international obligations to improve copyright protection in the digital environment, confront its enormous piracy challenges, and remove the remaining barriers to its creative marketplace. Vietnam must take more affirmative enforcement actions against piracy, such as issuing deterrent administrative penalties against infringers, and undertaking criminal prosecutions, beginning with major online piracy operations that are based in Vietnam. Vietnam’s piracy problems would also be reduced if the country removed its highly restrictive market access barriers, which, by limiting Vietnamese consumers’ access to legitimate content, pushes them towards illegal alternatives. IIPA hopes that the Government of Vietnam will support procedures developed by a group of motion picture rights holders in consultation with Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to ensure that online infringing content is taken down and such content does not reappear. The government should also address concerns with the Copyright Office of Vietnam (COV), which is grossly understaffed, and has not taken any action to reform the dysfunctional collective management organization for music producers. -

Vietnam | Cambodia | Laos | Myanmar

Vietnam | Cambodia | Laos | Myanmar Introduction Cambodia Most people know of Cambodia as home to the crowning glory of Southeast Asia – the magnificent temples at Angkor Wat, but visitors are often surprised at how much more this small country has to offer. Angkor Wat is simply unmissable, but take a little more time to explore Phnom Penh, the exciting, bustling gateway to the country; Tonle Sap lake, the largest in Southeast Asia; Sihanoukville, an increasingly chic beach destination; and Mekong River town Kratie, where lucky visitors may spot endangered Mekong river dolphins. For those wishing to learn more about the country’s recent history, Tuol Sleng prison and the ‘Killing Fields’ of Choeung Ek provide a chilling insight into Cambodia’s darkest hours. Cambodia is at once captivating, enchanting, confronting and inspirational. The country has emerged from a tumultuous period of civil war with a renewed sense of creativity and optimism. Be charmed by its friendly, welcoming people, and explore the country's rich heritage, from religious monuments and colonial-era architecture to a thriving art scene. Phnompenh The Cambodia ’s commercial and political hub. It is also the gateway to the tem- ples of Angkor in the west, the beaches of Sihanoukville on the southern coast and the hill tribe minority in the Northern Province . Revitalized capital city with temples and French colonial architecture blended with a cosmopolitan restau- rants, hotels, and night life scenes.The capital of Cambodia dates back to an event in the year 1327. It is said that a rich widow named Don Penh found a tree with 5 Buddhas in it.