Armed Conflicts Between the Kachin Independence Organization and Myanmar Army: a Conflict Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar/Burma - Kachin

Myanmar/Burma - Kachin minorityrights.org/minorities/kachin/ June 19, 2015 Profile The Kachin encompass a number of ethnic groups speaking almost a dozen distinct languages belonging to the Tibeto-Burman linguistic family who inhabit the same region in the northern part of Burma on the border with China, mainly in Kachin State. Strictly speaking, these languages are not necessarily closely related, and the term Kachin at times is used to refer specifically to the largest of the groups (the Kachin or Jingpho/Jinghpaw) or to the whole grouping of Tibeto-Burman speaking minorities in the region, which include the Maru, Lisu, Lashu, etc. The exact Kachin population is unknown due to the absence of reliable census data in Burma for more than 60 years. Most estimates suggest there may in the vicinity of 1 million Kachin in the country. The Kachin, as well as the Chin, are one of Burma’s largest Christian minorities: though once again difficult to assess, it is generally thought that between two-thirds and 90 per cent of Kachin are Christians, with others following animist practices or Buddhists. Historical context It is generally thought that the Kachin gradually moved south from their ancestral land on the Tibetan plateau through Yunnan in southern China to arrive in the northern region of what would become Burma sometime during the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries, making the Kachin relative newcomers. Their position in this borderland part of South-East Asia meant that the Kachin were often outside of the sphere of influence of Burman kings. Their strength was such by the Third Anglo-Burmese War of 1885 that, while the British were taking Mandalay, the Kachin were getting ready to take advantage of the Burman kingdom’s weakness to attack and take over Mandalay themselves. -

Analysis of the FPNCC/Northern Alliance and Myanmar Conflict Dynamics

Analysis of the FPNCC/Northern Alliance and Myanmar Conflict Dynamics acleddata.com/2018/07/21/analysis-of-the-fpncc-northern-alliance-and-myanmar-conflict-dynamics/ Elliott Bynum July 21, 2018 With the Myanmar military pressuring all ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) to sign the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), non-signatory EAOs have responded by forming a loose military alliance, called the Northern Alliance, to strengthen their position against the military. As with many alliances in Myanmar’s history, the cohesiveness and long-term viability of the alliance is uncertain. Increased military operations by the Myanmar military against the groups in this alliance, particularly the increased use of remote violence, has resulted in the alliance groups shifting their tactics both politically and militarily. In 2016, four EAOs formed the Northern Alliance. The driver behind the formation of the Northern Alliance was the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) which has been in conflict with the Myanmar military for several decades. From 1994-2011, the KIA had a bilateral ceasefire agreement with the Myanmar military which held. The conflict reignited in 2011 after the KIA rejected the military’s Border Guard Force (BGF) scheme which would have placed the KIA under the control of the military. At the time, the Myanmar military also had increased its presence in the Kachin region to guard the Chinese construction of the Myitsone Hydropower Dam which exacerbated tensions, leading eventually to the start of the current war. The KIA has since sought to strengthen its position by providing training and support to the Arakan Army (AA), the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), and the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA). -

A Kachin Case Study

MUSEUMS, DIASPORA COMMUNITIES AND DIASPORIC CULTURES A KACHIN CASE STUDY HELEN MEARS PHD 2019 0 Abstract This thesis adds to the growing body of literature on museums and source communities through addressing a hitherto under-examined area of activity: the interactions between museums and diaspora communities. It does so through a focus on the cultural practices and museum engagements of the Kachin community from northern Myanmar. The shift in museum practice prompted by increased interaction with source communities from the 1980s onwards has led to fundamental changes in museum policy. Indeed, this shift has been described as “one of the most important developments in the history of museums” (Peers and Brown, 2003, p.1). However, it was a shift informed by the interests and perspectives of an ethnocentric museology, and, for these reasons, analysis of its symptoms has remained largely focussed on the museum institution rather than the communities which historically contributed to these institutions’ collections. Moreover, it was a shift which did not fully take account of the increasingly mobile and transnational nature of these communities. This thesis, researched and written by a museum curator, was initiated by the longstanding and active engagement of Kachin people with historical materials in the collections of Brighton Museum & Art Gallery. In closely attending to the cultural interests and habits of overseas Kachin communities, rather than those of the Museum, the thesis responds to Christina Kreps’ call to researchers to “liberate our thinking from Eurocentric notions of what constitutes the museum and museological behaviour” (2003, p.x). Through interviews with individual members of three overseas Kachin communities and the examination of a range of Kachin-related cultural productions, it demonstrates the extent to which Kachin people, like museums, are highly engaged in heritage and cultural preservation, albeit in ways which are distinctive to normative museum practices of collecting, display and interpretation. -

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar

Identity Crisis: Ethnicity and Conflict in Myanmar Asia Report N°312 | 28 August 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Legacy of Division ......................................................................................................... 4 A. Who Lives in Myanmar? ............................................................................................ 4 B. Those Who Belong and Those Who Don’t ................................................................. 5 C. Contemporary Ramifications..................................................................................... 7 III. Liberalisation and Ethno-nationalism ............................................................................. 9 IV. The Militarisation of Ethnicity ......................................................................................... 13 A. The Rise and Fall of the Kaungkha Militia ................................................................ 14 B. The Shanni: A New Ethnic Armed Group ................................................................. 18 C. An Uncertain Fate for Upland People in Rakhine -

New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State?

CRS INSIGHT New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State? February 15, 2019 (IN11046) | Related Author Michael F. Martin | Michael F. Martin, Specialist in Asian Affairs ([email protected], 7-2199) Approximately 250 Chin and Rakhine refugees entered into Bangladesh's Bandarban district in the first week of February, trying to escape the fighting between Burma's military, or Tatmadaw, and one of Burma's newest ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), the Arakan Army (AA). Bangladesh's Foreign Minister Abdul Momen summoned Burma's ambassador Lwin Oo to protest the arrival of the Rakhine refugees and the military clampdown in Rakhine State. Bangladesh has reportedly closed its border to Rakhine State. U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Myanmar Yanghee Lee released a press statement on January 18, 2019, indicating that heavy fighting between the AA and the Tatmadaw had displaced at least 5,000 people. She also called on the Rakhine State government to reinstate the access for international humanitarian organizations. The Conflict Between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw The AA was formed in Kachin State in 2009, with the support of the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). In 2015, the AA moved some of its soldiers from Kachin State to southwestern Chin State, and began attacking Tatmadaw security bases in Chin State and northern Rakhine State (see Figure 1). In late 2017, the AA shifted more of its operations into northeastern Rakhine State. According to some estimates, the AA has approximately 3,000 soldiers based in Chin and Rakhine States. Figure 1. Reported Clashes between Arakan Army and Tatmadaw Source: CRS, utilizing data provided by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). -

7 Publicversion Myanmar Janv2018

The Strategy and Tactics of Myanmar COIN Strategy since 2010 note OBSERVATOIRE ASIE DU SUD-EST 2017/2018 OBSERVATOIRE Note d’actualité n°7/8 de l’Observatoire de l’Asie du Sud-Est, cycle 2017-2018 Janvier 2018 Along with the recent democratization, the ongoing peace process has transformed the Counter Insurgency (COIN) strategy and tactics of the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw). Political reforms after 2010 created the new dynamic of civil-military relation, shifting paradigm in the COIN activities. Taking off from the old strategy of four-cut policy, COIN tactics vary, depend ing on the regions. From the conventional tactics with peace process as leverage in Kachin state, use of militia with the four-cut policy is also active in Shan States. Although militias still remain the backbone of the COIN operations, as the result of the Standard Army reform process, their role has soon to change. Maison de la Recherche de l’Inalco 2 rue de Lille 75007 Paris - France Tél. : +33 1 75 43 63 20 Fax. : +33 1 75 43 63 23 ww.centreasia.eu [email protected] siret 484236641.00037 List of the acronyms & abbreviations Introduction 1. Militias – Backbone of the COIN Introduction 2. COIN Operations in the Kachin State Insurgency and independence are two sides of the same Background of the conflict coin. Since 2010, the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw) Tatmadaw’s Tactics in Kachin State has adopted numbers of Counter Insurgency (COIN) Tatmadaw’s types of operations in Kachin strategies and tactics to expand the government State control area and reduce the contested areas controlled Resources by non-state actors: the ethnic and communist insurgents. -

Current Ethnic Issues (Kachin & Shan)

Current Ethnic Issues (Kachin & Shan) Report By Foreign Affairs United Nationalities Federal Council (UNFC) Date: 7th July, 2011 “Current Kachin Conflict & list of Internally Displaced People” 1) On June, 8th 2011 KIA arrested 3 servicemen of Burma Army Light Infantry Battalion 437 (Including 2 officers) who covertly entered into KIO’s restricted area to gather intelligence. At 5:00 pm, Burma Army soldiers stormed into KIO liaison office in Sang Gang Village and arbitrarily arrested Liaison officer Lance Corporal Chyang Ying. 2) On June 9th at 7:00am, 200 Burma Army soldiers marched into Sang Gang Post unannounced and started shooting at KIA troops. KIA shot back and fire fight lasted close to three hours. 3 Burma Army soldiers killed and 6 injured. And, 2 KIA soldiers injured. KIA negotiated with the Northern Command Burma Army to exchange 3 Burma Army captives for all of KIA servicemen captured in the past years and also Liaison Officer Chyang Ying. Burma Army replied that all other captives have been forwarded to the courts since we are the government that is governed by the rule of law. However, we still have Chyang Ying in our custody, and if desired he could be exchanged for the 3 captives in your custody. 3) On June 10th 2011, in good faith, KIA obliged to their request, and release the 2 officers and 1 private. When Chyang Ying was to be returned, five Burma Army soldiers carried his corpse to bring back his dead body. The Liaison Officer was inhumanely tortured and brutally beaten during interrogation and laid under the sun on the front lawn of the Burma Army post. -

Finding an Endgame in Kachin State the KIO’S Strategies for Finding a Resolution to the Conflict

EBO Background Paper - No .3 | 2018 September 2018 AUTHOR | Paul Keenan Finding an Endgame in Kachin State The KIO’s strategies for finding a resolution to the conflict Since 9 June 2011, Kachin State has seen open (CEFU). The Committee’s purpose was to conflict between the Kachin Independence Army consolidate a political front at a time when the and the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military). The Kachin ceasefire groups faced perceived imminent attacks Independence Organisation had signed a ceasefire by the Tatmadaw. However, in November 2010 agreement with the regime in 1994 and since then shortly after the Myanmar elections, the political had lived in relative peace until the ceasefire was grouping was transformed into a military united broken by the Tatmadaw in June 2011. front. At a conference held from the 12-16 February 2011, CEFU declared its dissolution and the The increased territorial infractions by the formation of the United Nationalities Federal Tatmadaw combined with economic exploitation Council (UNFC). The UNFC, which was at that time by China in Kachin territory, especially the comprised of 12 ethnic organisations1, stated that: construction of the Myitsone Hydropower Dam, left the Kachin Independence Organisation with very The goal of the UNFC is to establish the little alternative but to return to armed resistance future Federal Union (of Myanmar) and to prevent further abuses of its people and their the Federal Union Army is formed for territory’s natural resources. Despite this, however, giving protection to the people of the the political situation since the beginning of country.2 hostilities has changed significantly. -

Kachin State WATCH

H U M A N R I G H T S “UNTOLD MISERIES” Wartime Abuses and Forced Displacement in Kachin State WATCH “Untold Miseries” Wartime Abuses and Forced Displacement in Burma’s Kachin State Copyright © 2012 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-874-0 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MARCH 2012 1-56432-874-0 “Untold Miseries” Wartime Abuses and Forced Displacement in Burma’s Kachin State Map of Burma ...................................................................................................................... i Detailed Map of Kachin State ............................................................................................. -

The Kachin-China Border

Border Lives The Kachin-China Border May 2019 Border Lives The Kachin-China Border Table of Contents List of acronyms iii 1. Introduction 1 2. Summary of Key Findings 4 3. The Myanmar Kachin-China border 9 3.1 Theoretical framework: borders as conceived, perceived and lived 10 3.2 Existing information about life in the Myanmar/Kachin-China border 10 3.2.1 Livelihoods 11 3.2.2 Education 11 3.2.3 Pressures on family and marriage 13 4. Research Design and Methodology 14 4.1 Research Questions 14 4.2 Scoping trips 14 4.3 Selection of sites 15 4.4 Selection of participants 15 4.5 Interview process 16 4.6 Field Work Round One 17 4.7 Field Work Round Two 18 4.8 Analysis 18 Findings 19 5. Mai Ja Yang 19 5.1 Livelihoods 20 i 5.1.1 Migrant labour 20 5.1.2 IDP camps 22 5.1.3 Mai Ja Yang 26 5.2 Education 27 5.3 Families and marriage 29 5.4 Governance 32 6. Hpimaw 36 6.1 Livelihoods 36 6.2 Education 41 6.3 Families and marriage 44 6.4 Governance 48 7. Conclusion 54 7.1 Implications for future research 55 Bibliography 56 ii Border Lives : The Kachin-China Border List of acronyms BGF Border Guard Force CPB Communist Party of Burma CSO Civil Society Organisation EAO Ethnic Armed Organisation EMReF Enlightened Myanmar Research Foundation GAD General Administration Department ID Identity Document IDP Internally Displaced Person KBC Kachin Baptist Convention KDNG Kachin Development Networking Group KIA Kachin Independence Army KIO Kachin Independence Organisation MMK Myanmar Kyats NDA-K New Democratic Army-Kachin NRC National Registration Card VTA Village Tract Administrator Currency Most wage and price amounts quoted during interviews in Kachin-China border areas were in the Chinese currency, the Yuan. -

Jingpho Dialogue Texts with Grammatical Notes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Prometheus-Academic Collections Asian and African Languages and Linguistics, No.7, 2012 Jingpho Dialogue Texts with Grammatical Notes KURABE, Keita JSPS / Kyoto University Jingpho is a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in Kachin State and Shan State, Burma and adjacent areas of China and India. This paper provides dialogue texts with a brief grammatical sketch of the Myitkyina-Bhamo dialect, the most standard dialect of Jingpho in Burma. General information on Jingpho is provided in section 1. In section 2, I describe the phonological system of this language. An overview of morphology and syntax is given in section 3 and 4 respectively. Section 5 provides dialogue texts in Jingpho, consisting of over 200 sentences. Keywords: Jingpho, Kachin, Myitkyina-Bhamo dialect, Tibeto-Burman, Sino-Tibetan 1. Introduction 2. Phonology 3. Morphology 4. Syntax 5. Text 1. Introduction The Jingpho language is a Tibeto-Burman language spoken primarily in Kachin State and northern Shan State of Burma, southwestern Yunnan in China and northeastern India. The total Jingpho population is estimated to be 650,000 (Bradley 1996), and most speakers live in northern Burma. Although there are several dialects of Jingpho in Burma, most have not been sufficiently described. Kurabe (2012b) is a preliminary description of the Duleng dialect, and Kurabe (2012c) is a preliminary description of the Dingga dialect. Kurabe (2012g) provides a brief overview of Jingpho dialects known to date with their geographic distribution and tentative subgrouping based on previous studies, linguistic facts and native speakers’ reports. -

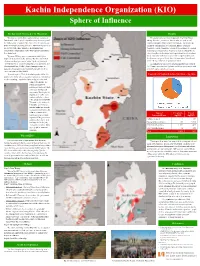

Control of Cropland in Kachin State - Sq

Kachin Independence Organization (KIO) Sphere of Influence Background: Insurgency in Myanmar Results Myanmar is a multiethnic country and was a colony of The global land-cover data map provided by ESA Climate Britain until 1948. It practiced parliamentary democracy until Change Initiative (2010) is used to calculate the total area of the military took a coup in 1962. Since then, the country was cropland (in square kilometers) in Kachin State. For simplicity, under military dictatorship until 2011. Myanmar has also been (irrigated croplands, rain-fed croplands, mosaic croplands/ in civil war with ethnic minorities including Kachin vegetation, mosaic vegetation/ croplands) are grouped as cropland. Independence Organization (KIO) who fight for autonomy in (closed to open broadleaved evergreen or semi-deciduous forest, their home land. closed broadleaved deciduous forest, open broadleaved deciduous Myanmar Military wrote a constitution which gives forest, closed needleleaved evergreen forest, open needleleaved unprecedented powers to the military. The November 2010 deciduous or evergreen forest, closed to open mixed broadleaved election was largely seen as a “sham” by the international and needleleaved forest) are grouped as forest. community. The de facto military party, Union Solidarity and According to the land-cover data, Kachin State has a total of Development Party (USDP) claimed outright victory. A 4,671 square kilometers of cropland, and 36 percent of which falls nominal civilian government led by ex-general Thein Sein in the KIO sphere of influence zones. came into power in March 2011. To much surprise, Thein Sein administration initiated a Control of Cropland in Kachin State - Sq. Km. number of reforms: release of political prisoners, relaxation of media censorship, economic reforms and peace talks with ethnic rebel groups.