Invited Lectures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sailors, Tailors, Cooks, and Crooks: on Loanwords and Neglected Lives in Indian Ocean Ports

Itinerario, Vol. 42, No. 3, 516–548. © 2018 Research Institute for History, Leiden University. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/S0165115318000645 Sailors, Tailors, Cooks, and Crooks: On Loanwords and Neglected Lives in Indian Ocean Ports TOM HOOGERVORST* E-mail: [email protected] A renewed interested in Indian Ocean studies has underlined possibilities of the transnational. This study highlights lexical borrowing as an analytical tool to deepen our understanding of cultural exchanges between Indian Ocean ports during the long nineteenth century, comparing loanwords from several Asian and African languages and demonstrating how doing so can re-establish severed links between communities. In this comparative analysis, four research avenues come to the fore as specifically useful to explore the dynamics of non-elite contact in this part of the world: (1) nautical jargon, (2) textile terms, (3) culinary terms, and (4) slang associated with society’s lower strata. These domains give prominence to a spectrum of cultural brokers frequently overlooked in the wider literature. It is demonstrated through con- crete examples that an analysis of lexical borrowing can add depth and substance to existing scholarship on interethnic contact in the Indian Ocean, providing methodolo- gical inspiration to examine lesser studied connections. This study reveals no unified linguistic landscape, but several key individual connections between the ports of the Indian Ocean frequented by Persian, Hindustani, and Malay-speaking communities. -

Central Eurasian Studies Society Fourth Annual Conference October

Central Eurasian Studies Society Fourth Annual Conference October 2- 5, 2003 Hosted by: Program on Central Asia and the Caucasus Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Mass., USA Table of Contents Conference Schedule ................................................................................... 1 Film Program ......................................................................................... 2 Panel Grids ................................................................................................ 3 List of Panels .............................................................................................. 5 Schedule of Panels ...................................................................................... 7 Friday • Session I • 9:00 am-10:45 am ..................................................... 7 Friday • Session II • 11:00 am-12:45 pm .................................................. 9 Friday • Session III • 2:00 pm-3:45 pm .................................................. 11 Friday • Session IV • 4:00 pm-5:45 pm .................................................. 12 Saturday • Session I • 9:00 am-10:45 am ............................................... 14 Saturday • Session II • 11:00 am-12:45 pm ............................................ 16 Saturday • Session III • 2:00 pm-3:45 pm .............................................. 18 Saturday • Session IV • 4:00 pm-6:30 pm .............................................. 20 Sunday • Session I • 9:00 am-10:45 am ................................................ -

The Impact of Arabic Orthography on Literacy and Economic Development in Afghanistan

International Journal of Education, Culture and Society 2019; 4(1): 1-12 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijecs doi: 10.11648/j.ijecs.20190401.11 ISSN: 2575-3460 (Print); ISSN: 2575-3363 (Online) The Impact of Arabic Orthography on Literacy and Economic Development in Afghanistan Anwar Wafi Hayat Department of Economics, Kabul University, Kabul, Afghanistan Email address: To cite this article: Anwar Wafi Hayat. The Impact of Arabic Orthography on Literacy and Economic Development in Afghanistan. International Journal of Education, Culture and Society . Vol. 4, No. 1, 2019, pp. 1-12. doi: 10.11648/j.ijecs.20190401.11 Received : October 15, 2018; Accepted : November 8, 2018; Published : January 31, 2019 Abstract: Currently, Pashto and Dari (Afghan Persian), the two official languages, and other Afghan languages are written in modified Arabic alphabets. Persian adopted the Arabic alphabets in the ninth century, and Pashto, in sixteenth century CE. This article looks at how the Arabic Orthography has hindered Literacy and Economic development in Afghanistan. The article covers a comprehensive analysis of Arabic Orthography adopted for writing Dari and Pashto, a study of the proposed Arabic Language reforms, and research conducted about reading and writing difficulty in Arabic script by Arab intellectuals. The study shows how adopting modified Latin alphabets for a language can improve literacy level which further plays its part in the economic development of a country. The article dives into the history of Romanization of languages in the Islamic World and its impact on Literacy and economic development in those countries. Romanization of the Afghan Official languages and its possible impact on Literacy, Economy, and Peace in Afghanistan is discussed. -

The Case of the Iraqi Disputed Territories Declaration Submitted By

Title: Education as an Ethnic Defence Strategy: The Case of the Iraqi Disputed Territories Declaration Submitted by Kelsey Jayne Shanks to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics, October 2013. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Kelsey Shanks ................................................................................. 1 Abstract The oil-rich northern districts of Iraq were long considered a reflection of the country with a diversity of ethnic and religious groups; Arabs, Turkmen, Kurds, Assyrians, and Yezidi, living together and portraying Iraq’s demographic makeup. However, the Ba’ath party’s brutal policy of Arabisation in the twentieth century created a false demographic and instigated the escalation of identity politics. Consequently, the region is currently highly contested with the disputed territories consisting of 15 districts stretching across four northern governorates and curving from the Syrian to Iranian borders. The official contest over the regions administration has resulted in a tug-of-war between Baghdad and Erbil that has frequently stalled the Iraqi political system. Subsequently, across the region, minority groups have been pulled into a clash over demographic composition as each disputed districts faces ethnically defined claims. The ethnic basis to territorial claims has amplified the discourse over linguistic presence, cultural representation and minority rights; and the insecure environment, in which sectarian based attacks are frequent, has elevated debates over territorial representation to the height of ethnic survival issues. -

TURKMEN, TURKMENO, TURKMÈNE Language Family

TURKMEN, TURKMENO, TURKMÈNE Language family: Altaic, Turkic, Southern, Turkmenian. Language codes: ISO 639-1 tk ISO 639-2 tuk ISO 639-3 tuk Glottolog: turk1304. Linguasphere: part of 44-AAB-a. ﺗﻮرﮐﻤﻦ ,Beste izen batzuk (Türkmençe, Türkmen dili, Түркменче, Түркмен дили :(ﺗﻴﻠی ,ﺗﻮرﮐﻤﻨﭽﻪ torkomani alt turkmen [TCK]. turkman alt turkmen [TCK]. trukhmen alt turkmen [TCK]. trukhmeny alt turkmen [TCK]. trukmen alt turkmen [TCK]. trukmen dial turkmen [TCK]. turkmani alt turkmen [TCK]. turkmanian alt turkmen [TCK]. turkmen [TCK] hizk, Turkmenistan; baita Afganistan, Alemania, AEB, Iran, Irak, Kazakstan, Kirgizistan, Pakistan, Errusia (Asia), Tajikistan, Turkia (Asia) eta Uzbekistan ere. turkmenler alt turkmen [TCK]. turkoman alt turkmen [TCK]. turkomani alt turkmen [TCK]. turkomans alt turkmen [TCK]. AFGANISTAN turkmen (turkoman, trukmen, turkman) [TCK] 500.000 hiztun (1995). Turkmenistanen mugan zehar, bereziki Fariab eta Badghis probintzien mugetan. Batzuk Andkhoi eta Herat hirietan. Altaic, Turkic, Southern, Turkmenian. Dialektoak: salor, teke (tekke, chagatai, jagatai), ersari, sariq, yomut. Dialekto diferentzia markatuak. Seguruenez ersari dialektoa nagusi Afganistanen. Helebitasuna pashtoerarekin. Errefuxiatuen talde bat Kabulen. Sirian ‘turkmeniar’ deitu herritarrak azerbaijaneraren hiztunak dira. Arabiar idazkera. Pertsona eskolatuenak gai dira zirilikoz irakurtzeko. Egunkariak. Ikus sarrera nagusia Turkmenistanen. IRAN turmen (torkomani) [TCK] 2.000.000 hiztun (1997), edo herriaren % 3,17 (1997). Ipar- ekialdea, batez ere Mazandaran Probintzia, Turkmenistanen mugan zehar; garrantzizko zentroak dira Gonbad-e Kavus eta Pahlavi Dezh. Altaic, Turkic, Southern, Turkmenian. Dialektoak: anauli, khasarli, nerezim, nokhurli (nohur), chavdur, esari (esary), goklen (goklan), salyr, saryq, teke (tekke), yomud (yomut), trukmen. Elebitasuna farsierarekin. Iranen ez da hizkuntza literarioa. Asko erdi-nomadak dira. Talde etnikoak: yomut, goklan. Hauek irakur dezakete arabiar idazkera. Irrati programak. Ikus sarrera nagusia Turkmenistanen. -

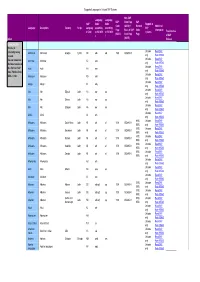

Supported Languages in Unicode SAP Systems Index Language

Supported Languages in Unicode SAP Systems Non-SAP Language Language SAP Code Page SAP SAP Code Code Support in Code (ASCII) = Blended Additional Language Description Country Script Languag according according SAP Page Basis of SAP Code Information e Code to ISO 639- to ISO 639- systems Translated as (ASCII) Code Page Page 2 1 of SAP Index (ASCII) Release Download Info: AThis list is Unicode Read SAP constantly being Abkhazian Abkhazian Georgia Cyrillic AB abk ab 1500 ISO8859-5 revised. only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP You can download Achinese Achinese AC ace the latest version of only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP this file from SAP Acoli Acoli AH ach Note 73606 or from only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP SDN -> /i18n Adangme Adangme AD ada only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP Adygei Adygei A1 ady only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP Afar Afar Djibouti Latin AA aar aa only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP Afar Afar Eritrea Latin AA aar aa only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP Afar Afar Ethiopia Latin AA aar aa only Note 895560 Unicode Read SAP Afrihili Afrihili AI afh only Note 895560 6100, Unicode Read SAP Afrikaans Afrikaans South Africa Latin AF afr af 1100 ISO8859-1 6500, only Note 895560 6100, Unicode Read SAP Afrikaans Afrikaans Botswana Latin AF afr af 1100 ISO8859-1 6500, only Note 895560 6100, Unicode Read SAP Afrikaans Afrikaans Malawi Latin AF afr af 1100 ISO8859-1 6500, only Note 895560 6100, Unicode Read SAP Afrikaans Afrikaans Namibia Latin AF afr af 1100 ISO8859-1 6500, only Note 895560 6100, Unicode Read SAP Afrikaans Afrikaans Zambia -

Download 1 File

Strokes and Hairlines Elegant Writing and its Place in Muslim Book Culture Adam Gacek Strokes and Hairlines Elegant Writing and its Place in Muslim Book Culture An Exhibition in Celebration of the 60th Anniversary of The Institute of Islamic Studies, McGill University February 11– June 30, 2013 McLennan Library Building Lobby Curated by Adam Gacek On the front cover: folio 1a from MS Rare Books and Special Collections AC156; for a description of and another illustration from the same manuscript see p.28. On the back cover: photograph of Morrice Hall from Islamic Studies Library archives Copyright © 2013 McGill University Library ISBN 978-1-77096-209-5 3 Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................5 Introduction ........................................................................................7 Case 1a: The Qurʾan ............................................................................9 Case 1b: Scripts and Hands ..............................................................17 Case 2a: Calligraphers’ Diplomas ...................................................25 Case 2b: The Alif and Other Letterforms .......................................33 Case 3a: Calligraphy and Painted Decoration ...............................41 Case 3b: Writing Implements .........................................................49 To a Fledgling Calligrapher .............................................................57 A Scribe’s Lament .............................................................................58 -

BGN/PCGN Romanization Guide

TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction II. Approved Romanization Systems and Agreements Amharic Arabic Armenian Azeri Bulgarian Burmese Byelorussian Chinese Characters Georgian Greek Hebrew Japanese Kana Kazakh Cyrillic Khmer (Cambodian) Kirghiz Cyrillic Korean Lao Macedonian Maldivian Moldovan Mongolian Cyrillic Nepali Pashto Persian (Farsi and Dari) Russian Serbian Cyrillic Tajik Cyrillic Thai Turkmen Ukrainian Uzbek III. Roman-script Spelling Conventions Faroese German Icelandic North Lappish IV. Appendices A. Unicode Character Equivalents B. Optimizing Software and Operating Systems to Display BGN-approved geographic names Table . Provenance and Status of Romanization Systems Contained in this Publication Transliteration Date Class Originator System Approved BGN/PCGN Amharic System 967 967 System BGN/PCGN Arabic 96 System 96 System BGN/PCGN Armenian System 98 98 System Roman Alphabet Azeri 00 Azeri Government 99 Spelling Convention BGN/PCGN Bulgarian System 9 9 System BGN/PCGN Burmese Burmese Government Agreement 970 970 Agreement 907 System BGN/PCGN Byelorussian 979 System 979 System Xinhua Zidian Chinese Pinyin System Agreement 979 dictionary. Commercial Press, Beijing 98. Chinese Wade-Giles Agreement 979 System BGN/PCGN Faroese Roman Script Spelling 968 Spelling Convention Convention BGN/PCGN 98 System 98 Georgian System BGN/PCGN German Roman Script Spelling 986 Spelling Convention Convention Greek ELOT Greek Organization for Agreement 996 7 System Standardization BGN/PCGN Hebrew Hebrew Academy Agreement 96 96 System System Japanese -

Turkmen Alphabet

TYPE: 94-Character Graphic Character Set REGISTRATION NUMBER: 230 DATE OF REGISTRATION: 2000-09-14 ESCAPE SEQUENCE G0: ESC 2/8 2/1 4/4 G1: ESC 2/9 2/1 4/4 G2: ESC 2/10 2/1 4/4 G3: ESC 2/11 2/1 4/4 C0: - C1: - NAME Turkmen Alphabet DESCRIPTION An independent set of 94 graphic characters under provision of ISO/IEC 2022 SPONSOR MAJOR STATE INSPECTION "TURKMENSTANDARTLARY" ORIGIN Turkmen Standard TDS 565 FIELD OF UTILIZATION This set is intended for use in text and data processing applications and may also be used for information interchange. Pos. NAME Note* 2/1 EXCLAMATION MARK 0021 2/2 QUOTATION MARK 0022 2/3 NUMBER SIGN 0023 2/4 DOLLAR SIGN 0024 2/5 PERCENT SIGN 0025 2/6 AMPERSAND 0026 2/7 APOSTROPHE 0027 2/8 LEFT PARENTHESIS 0028 2/9 RIGHT PARENTHESIS 0029 2/10 ASTERISK 002A 2/11 PLUS SIGN 002B 2/12 COMMA 002C 2/13 HYPHEN-MINUS 002D 2/14 FULL STOP (PERIOD, DECIMAL POINT) 002E 2/15 SOLIDUS (SLASH) 002F 3/0 DIGIT ZERO 0030 3/1 DIGIT ONE 0031 3/2 DIGIT TWO 0032 3/3 DIGIT THREE 0033 3/4 DIGIT FOUR 0034 3/5 DIGIT FIVE 0035 3/6 DIGIT SIX 0036 3/7 DIGIT SEVEN 0037 3/8 DIGIT EIGHT 0038 3/9 DIGIT NINE 0039 3/10 COLON 003A 3/11 SEMI-COLON 003B 3/12 LESS-THAN SIGN 003C 3/13 EQUAL SIGN 003D 3/14 GREATER-THAN SIGN 003E 3/15 QUESTION MARK 003F 4/0 COMMERCIAL AT 0040 4/1 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER A 0041 4/2 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER B 0042 4/3 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER C WITH 00C7 CEDILLA 4/4 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER D 0044 4/5 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER E 0045 4/6 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER A WITH 00C4 DIAERESIS 4/7 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER F 0046 4/8 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER G 0047 4/9 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER H 0048 4/10 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER I 0049 4/11 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER J 004A Pos. -

Cahiers D'asie Centrale, 26

Cahiers d’Asie centrale 26 | 2016 1989, année de mobilisations politiques en Asie centrale 1989, a Year of Political Mobilisations in Central Asia Ferrando Olivier (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/asiecentrale/3218 ISSN : 2075-5325 Éditeur Éditions De Boccard Édition imprimée Date de publication : 30 novembre 2016 ISBN : 978-2-84743-161-2 ISSN : 1270-9247 Référence électronique Ferrando Olivier (dir.), Cahiers d’Asie centrale, 26 | 2016, « 1989, année de mobilisations politiques en Asie centrale » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 novembre 2017, consulté le 08 mars 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/asiecentrale/3218 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 8 mars 2020. © Tous droits réservés 1 L’année 1989 symbolise, dans la mémoire collective, la fin du communisme en Europe, mais il faudra attendre plus de deux ans pour assister à la dissolution de l’Union soviétique et à l’accès des cinq républiques d’Asie centrale à leur indépendance. Pourtant, dès le début de l’année 1989, avant-même la chute du mur de Berlin, la région fut le siège de plusieurs signes avant-coureurs : le retrait de l’Armée Rouge en Afghanistan ; l’arrêt des essais nucléaires soviétiques au Kazakhstan ; l’apparition des premières tensions interethniques dans la vallée du Ferghana ; l’adoption par chaque république d’une loi sur la langue. Autant de moments qui montrent combien l’année 1989 a marqué l’histoire récente de l’Asie centrale. Ce nouveau numéro des Cahiers d’Asie centrale est donc consacré à l’étude des transformations sociales et politiques survenues au cours de l’année 1989 afin de comprendre à quel point cette année constitue un moment fondateur des mobilisations politiques en Asie centrale. -

Free Foreign Language Teacher Resources from the Language Resource Centers

Free Foreign Language Teacher Resources from the Common LRC Website Language Resource Centers http://www.nflrc.org Download a PDF with hotlinks from the LRC Common Website at http://www.nflrc.org/lrc_broc_full.pdf Visit the LRC Common Website for regular updates and additional information. Visit the LRC Common Website for information on summer workshops, institutes, and scholarship opportunities Last updated 09/2013 Free Resources from Language Resource Centers For updated information visit the LRC common website at www.nflrc.org Page 1 of 26 Entries marked with * are new for 2012-2013 / Entries marked with ** have been expanded in 2012-2013 Teacher Guides & Tools – General Alphabet Charts Full color alphabet charts with transcription and sound examples, IPA symbols, and letter CeLCAR http://iub.edu/~celcar/language_informat names for Azerbaijani, Dari, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Mongolian, Pashto, Tajiki, Turkmen, Uyghur, ional_materials.php Uzbek. Arabic Online Corpus Online corpus mostly from the Arabic press and search tools that provide students, teachers, NMELRC http://nmelrc.org/online-arabic-corpus and material developers powerful tools to access authentic language in context. Bringing the Standards to the Handbook for teachers on how to implement the standards in their classrooms. NFLRC – K12 archived Classroom: A Teacher’s Guide http://web.archive.org/web/2010110314 5446/http://nflrc.iastate.edu/pubs/standa rds/standards.html **California Subject Examinations for These materials attempt to provide CSET-Arabic takers with basic review notes and practice LARC http://larc.sdsu.edu/downloads/CSET/CSE Teachers (CSET): Arabic Language questions covering solely domains in Subtest I: General Linguistics and Linguistics of the TArabicLanguagePowerPoint.pdf Preparation Material Target Language, and Literary and Cultural Texts and Traditions. -

Articulating National Identity in Turkmenistan: Inventing Tradition Through Myth, Cult and Language

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Faculty and Researcher Publications Faculty and Researcher Publications 2014 Articulating national identity in Turkmenistan: inventing tradition through myth, cult and language Clement, Victoria þÿNations and Nationalism 20 (3), 2014, 546 562. http://hdl.handle.net/10945/46172 JOURNAL OF THE ASSOCIATION bs_bs_banner NATIONS AND FOR THE STUDY OF ETHNICITY AS NATIONALISM AND NATIONALISM EN Nations and Nationalism 20 (3), 2014, 546–562. DOI: 10.1111/nana.12052 Articulating national identity in Turkmenistan: inventing tradition through myth, cult and language VICTORIA CLEMENT Department of National Security Affairs, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA, USA ABSTRACT. A study of myth, cult, and language as tools of state power, this paper analyzes ways national identity was constructed and articulated in one state. When Türkmenistan became independent in 1991 its first president, Saparmyrat Nyýazow, promoted himself as the ‘savior’ of the nation by reconceptualising what it meant to be Türkmen. Myth, public texts and language policy were used to construct this identity. While they were the targets of the state’s cultural products, Türkmen citizens contrib- uted to the processes of cultural production. Nyýazow legitimised his authoritarian leadership, first by co-opting Türkmen citizens to support his regime, and then by coercing them as participants in his personality cult. The paper concludes that Nyýazow used the production of culture, ‘invented tradition’ in Hobsbawm’s sense, to bolster his agenda and further his own power. It also argues that the exaggerated cult of personality Nyýazow cultivated limited his achievements, rather than solidifying them. KEYWORDS: agency, cult of personality, invented tradition, myth, national identity The construction of post-Soviet national identity in Turkmenistan had much to do with totalitarianism, control, and power.