Somatic Incompatibility in Agaricus Bitorquis (Quel.) Sacc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chemical Elements in Ascomycetes and Basidiomycetes

Chemical elements in Ascomycetes and Basidiomycetes The reference mushrooms as instruments for investigating bioindication and biodiversity Roberto Cenci, Luigi Cocchi, Orlando Petrini, Fabrizio Sena, Carmine Siniscalco, Luciano Vescovi Editors: R. M. Cenci and F. Sena EUR 24415 EN 2011 1 The mission of the JRC-IES is to provide scientific-technical support to the European Union’s policies for the protection and sustainable development of the European and global environment. European Commission Joint Research Centre Institute for Environment and Sustainability Via E.Fermi, 2749 I-21027 Ispra (VA) Italy Legal Notice Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of this publication. Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server http://europa.eu/ JRC Catalogue number: LB-NA-24415-EN-C Editors: R. M. Cenci and F. Sena JRC65050 EUR 24415 EN ISBN 978-92-79-20395-4 ISSN 1018-5593 doi:10.2788/22228 Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union Translation: Dr. Luca Umidi © European Union, 2011 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged Printed in Italy 2 Attached to this document is a CD containing: • A PDF copy of this document • Information regarding the soil and mushroom sampling site locations • Analytical data (ca, 300,000) on total samples of soils and mushrooms analysed (ca, 10,000) • The descriptive statistics for all genera and species analysed • Maps showing the distribution of concentrations of inorganic elements in mushrooms • Maps showing the distribution of concentrations of inorganic elements in soils 3 Contact information: Address: Roberto M. -

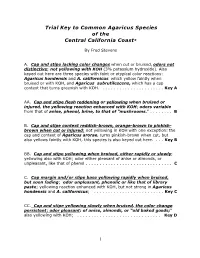

Trail Key to Common Agaricus Species of the Central California Coast

Trial Key to Common Agaricus Species of the Central California Coast* By Fred Stevens A. Cap and stipe lacking color changes when cut or bruised, odors not distinctive; not yellowing with KOH (3% potassium hydroxide). Also keyed out here are three species with faint or atypical color reactions: Agaricus hondensis and A. californicus which yellow faintly when bruised or with KOH, and Agaricus subrutilescens, which has a cap context that turns greenish with KOH. ......................Key A AA. Cap and stipe flesh reddening or yellowing when bruised or injured, the yellowing reaction enhanced with KOH; odors variable from that of anise, phenol, brine, to that of “mushrooms.” ........ B B. Cap and stipe context reddish-brown, orange-brown to pinkish- brown when cut or injured; not yellowing in KOH with one exception: the cap and context of Agaricus arorae, turns pinkish-brown when cut, but also yellows faintly with KOH, this species is also keyed out here. ...Key B BB. Cap and stipe yellowing when bruised, either rapidly or slowly; yellowing also with KOH; odor either pleasant of anise or almonds, or unpleasant, like that of phenol ............................... C C. Cap margin and/or stipe base yellowing rapidly when bruised, but soon fading; odor unpleasant, phenolic or like that of library paste; yellowing reaction enhanced with KOH, but not strong in Agaricus hondensis and A. californicus; .........................Key C CC. Cap and stipe yellowing slowly when bruised, the color change persistent; odor pleasant: of anise, almonds, or “old baked goods;” also yellowing with KOH; .............................. Key D 1 Key A – Species lacking obvious color changes and distinctive odors A. -

Catalogue of Fungus Fair

Oakland Museum, 6-7 December 2003 Mycological Society of San Francisco Catalogue of Fungus Fair Introduction ......................................................................................................................2 History ..............................................................................................................................3 Statistics ...........................................................................................................................4 Total collections (excluding "sp.") Numbers of species by multiplicity of collections (excluding "sp.") Numbers of taxa by genus (excluding "sp.") Common names ................................................................................................................6 New names or names not recently recorded .................................................................7 Numbers of field labels from tables Species found - listed by name .......................................................................................8 Species found - listed by multiplicity on forays ..........................................................13 Forays ranked by numbers of species .........................................................................16 Larger forays ranked by proportion of unique species ...............................................17 Species found - by county and by foray ......................................................................18 Field and Display Label examples ................................................................................27 -

Redalyc.Characterisation and Cultivation of Wild Agaricus Species from Mexico

Micología Aplicada International ISSN: 1534-2581 [email protected] Colegio de Postgraduados México Martínez Carrera, D.; Bonilla, M.; Martínez, W.; Sobal, M.; Aguilar, A.; Pellicer González, E. Characterisation and cultivation of wild Agaricus species from Mexico Micología Aplicada International, vol. 13, núm. 1, january, 2001, pp. 9-24 Colegio de Postgraduados Puebla, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=68513102 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative MICOLOGIAW AILDPLICADA AGARICUS INTERNATIONAL SPECIES FROM, 13(1), MEXICO 2001, pp. 9-249 © 2001, PRINTED IN BERKELEY, CA, U.S.A. www.micaplint.com CHARACTERISATION AND CULTIVATION OF WILD AGARICUS SPECIES FROM MEXICO* D. MARTÍNEZ-CARRERA, M. BONILLA, W. MARTÍNEZ, M. SOBAL, A. AGUILAR AND E. PELLICER-GONZÁLEZ College of Postgraduates in Agricultural Sciences (CP), Campus Puebla, Mushroom Biotechnology, Apartado Postal 701, Puebla 72001, Puebla, Mexico. Fax: 22-852162. E-mail: [email protected] Accepted for publication October 12, 2000 ABSTRACT Germplasm preservation and genetic improvement of authentic wild species is fundamental for developing the mushroom industry of any country. In Mexico, strains of wild Agaricus species were isolated from diverse regions. Ten species were tentatively identified on the basis of fruit-body morphology: A. abruptibulbus Peck, A. albolutescens Zeller, A. augustus Fries, A. bisporus var. bisporus (Lange)Imbach, A. bitorquis (Quél.)Sacc., A. campestris Link : Fries, A. hortensis (Cooke)Pilàt, A. osecanus Pilát, A. -

Mushrooms of Southwestern BC Latin Name Comment Habitat Edibility

Mushrooms of Southwestern BC Latin name Comment Habitat Edibility L S 13 12 11 10 9 8 6 5 4 3 90 Abortiporus biennis Blushing rosette On ground from buried hardwood Unknown O06 O V Agaricus albolutescens Amber-staining Agaricus On ground in woods Choice, disagrees with some D06 N N Agaricus arvensis Horse mushroom In grassy places Choice, disagrees with some D06 N F FV V FV V V N Agaricus augustus The prince Under trees in disturbed soil Choice, disagrees with some D06 N V FV FV FV FV V V V FV N Agaricus bernardii Salt-loving Agaricus In sandy soil often near beaches Choice D06 N Agaricus bisporus Button mushroom, was A. brunnescens Cultivated, and as escapee Edible D06 N F N Agaricus bitorquis Sidewalk mushroom In hard packed, disturbed soil Edible D06 N F N Agaricus brunnescens (old name) now A. bisporus D06 F N Agaricus campestris Meadow mushroom In meadows, pastures Choice D06 N V FV F V F FV N Agaricus comtulus Small slender agaricus In grassy places Not recommended D06 N V FV N Agaricus diminutivus group Diminutive agariicus, many similar species On humus in woods Similar to poisonous species D06 O V V Agaricus dulcidulus Diminutive agaric, in diminitivus group On humus in woods Similar to poisonous species D06 O V V Agaricus hondensis Felt-ringed agaricus In needle duff and among twigs Poisonous to many D06 N V V F N Agaricus integer In grassy places often with moss Edible D06 N V Agaricus meleagris (old name) now A moelleri or A. -

Control of Fungal Diseases in Mushroom Crops While Dealing with Fungicide Resistance: a Review

microorganisms Review Control of Fungal Diseases in Mushroom Crops while Dealing with Fungicide Resistance: A Review Francisco J. Gea 1,† , María J. Navarro 1, Milagrosa Santos 2 , Fernando Diánez 2 and Jaime Carrasco 3,4,*,† 1 Centro de Investigación, Experimentación y Servicios del Champiñón, Quintanar del Rey, 16220 Cuenca, Spain; [email protected] (F.J.G.); [email protected] (M.J.N.) 2 Departamento de Agronomía, Escuela Politécnica Superior, Universidad de Almería, 04120 Almería, Spain; [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (F.D.) 3 Technological Research Center of the Champiñón de La Rioja (CTICH), 26560 Autol, Spain 4 Department of Plant Sciences, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 2JD, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Mycoparasites cause heavy losses in commercial mushroom farms worldwide. The negative impact of fungal diseases such as dry bubble (Lecanicillium fungicola), cobweb (Cladobotryum spp.), wet bubble (Mycogone perniciosa), and green mold (Trichoderma spp.) constrains yield and harvest quality while reducing the cropping surface or damaging basidiomes. Currently, in order to fight fungal diseases, preventive measurements consist of applying intensive cleaning during cropping and by the end of the crop cycle, together with the application of selective active substances with proved fungicidal action. Notwithstanding the foregoing, the redundant application of the same fungicides has been conducted to the occurrence of resistant strains, hence, reviewing reported evidence of resistance occurrence and introducing unconventional treatments is worthy to pave the way towards Citation: Gea, F.J.; Navarro, M.J.; Santos, M.; Diánez, F.; Carrasco, J. -

Phylogeny of the Genus Agaricus Inferred from Restriction Analysis of Enzymatically Amplified Ribosomal DNA

Fungal Genetics and Biology 20, 243–253 (1996) Article No. 0039 Phylogeny of the Genus Agaricus Inferred from Restriction Analysis of Enzymatically Amplified Ribosomal DNA Britt A. Bunyard,* Michael S. Nicholson,† and Daniel J. Royse‡ *USDA-ARS, Fort Detrick, Building 1301, Frederick, Maryland 21701; †Department of Biology, Grand Valley State University, Allendale, Michigan 49401; and ‡Department of Plant Pathology, Pennsylvania State University, 316 Buckhout Laboratory, University Park, Pennsylvania 16802 Accepted for publication November 15, 1996 Bunyard, B. A., Nicholson, M. S., and Royse, D. J. 1996. accounting for 37% of the total world production of Phylogeny of the genus Agaricus inferred from restriction cultivated mushrooms. Although much is known about A. analysis of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA. Fungal bisporus, several aspects remain unclear, especially those Genetics and Biology 20, 243–253. The 26S and 5S concerning its genetic life history (Kerrigan et al., 1993a; ribosomal RNA genes and the intergenic region between Royer and Horgen, 1991; Castle et al., 1988, 1987; Spear et the 26S and the 5S rRNA genes of the ribosomal DNA al., 1983; Royse and May, 1982a,b; Elliott, 1972; Raper et repeat of 21 species of Agaricus were amplified using PCR al., 1972; Jiri, 1967; Pelham, 1967; Evans, 1959; Kligman, and then digested with 10 restriction enzymes. Restriction 1943). Fundamental processes such as the segregation and fragment length polymorphisms were found among the 21 assortment of genes during meiosis remain poorly defined putative species of Agaricus investigated and used to (Kerrigan et al., 1993a; Summerbell et al., 1989; Royse and develop a phylogenetic tree of the evolutionary history of May, 1982a). -

Los Hongos En Extremadura

Los hongos en Extremadura Los hongos en Extremadura EDITA Junta de Extremadura Consejería de Agricultura y Medio Ambiente COORDINADOR DE LA OBRA Eduardo Arrojo Martín Sociedad Micológica Extremeña (SME) POESÍAS Jacinto Galán Cano DIBUJOS África García García José Antonio Ferreiro Banderas Antonio Grajera Angel J. Calleja FOTOGRAFÍAS Celestino Gelpi Pena Fernando Durán Oliva Antonio Mateos Izquierdo Antonio Rodríguez Fernández Miguel Hermoso de Mendoza Salcedo Justo Muñoz Mohedano Gaspar Manzano Alonso Cristóbal Burgos Morilla Carlos Tovar Breña Eduardo Arrojo Martín DISEÑO E IMPRESIÓN Indugrafic, S.L. DEP. LEGAL BA-570-06 I.S.B.N. 84-690-1014-X CUBIERTA Entoloma lividum. FOTO: C. GELPI En las páginas donde se incluye dibujo y poesía puede darse el caso de que no describan la misma seta, pues prima lo estético sobre lo científico. Contenido PÁGINA Presentación .................................................................................................................................................................................... 9 José Luis Quintana Álvarez (Consejero de Agricultura y Medio Ambiente. Junta de Extremadura) Prólogo ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 11 Gabriel Moreno Horcajada (Catedrático de Botánica de la Universidad de Alcalá de Henares, Madrid) Los hongos en Extremadura ................................................................................................................................................. -

Nuclear Migration and Mitochondrial Inheritance in the Mushroom Agaricus Bitorquis

Copyright 0 1988 by the Genetics Society of America Nuclear Migration and Mitochondrial Inheritance in the Mushroom Agaricus bitorquis William E. A. Hintz, James B. Anderson and Paul A. Horgen Mushroom Research Group, Center for Plant Biotechnology, Department of Botany, University of Toronto, Erindale Campus, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada L5L I C6 Manuscript received October 21, 1987 Revised copy accepted January 28, 1988 ABSTRACT Mitochondrial (mt) DNA restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) were used as genetic markers for following mitochondrialinheritance in themushroom Agaricus bitorquis. In many basidiomycetes, bilateral nuclear migration between paired homokaryotic mycelia gives rise to two discrete dikaryons which have identical nuclei but different cytoplasms. Although nuclear migration is rare in A. bitorquis, unidirectional nuclear migration occurred when a nuclear donating strain (8- l), was paired with anuclear recipient strain (34-2). The dikaryonrecovered over the nuclear recipient mate (Dik D) contained nuclei from both parents but only mitochondria from the recipient mate; thus nuclei of 8-1, but not mitochondria, migrated through the resident hyphae of 34-2 following hyphal anastomosis. The two mitochondrial types present in a dikaryon recovered at the junction of the two cultures (Dik A) segregated during vegetative growth. Dikaryotic cells having the 34-2 mitochondrial type grew faster than cellswith the 8-1 mitochondrial type. Fruitbodies, derived from a mixed population of cells having the same nuclearcomponents but different cytoplasms, were chimeric for mitochondrial type. The transmission of mitochondria was biased in favor of the 8-1 type in the spore progeny of the chimeric fruitbody. Protoplasts of dikaryon (Dik D), which contained both nuclear types but only the 34-2 mitochondrial type, were regenerated and homokaryons containing the 8-1 nuclear type and the 34-2 mitochondrial type were recovered. -

Compost Physico-Chemical Factors That Impact on Yield in Button Mushrooms, Agaricus Bisporus (Lge) and Agaricus Bitorquis (Quel) Saccardo

© Kamla-Raj 2012 J Agri Sci, 3(1): 49-54 (2012) Compost Physico-chemical Factors that Impact on Yield in Button Mushrooms, Agaricus bisporus (Lge) and Agaricus bitorquis (Quel) Saccardo M. G. Kariaga1, H. W. Nyongesa1, N. C. O. Keya1 and H. M. Tsingalia2 1Department of Sugar Technology, 2Department of Biological Sciences, Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, P.O Box 190- 50100, Kakamega, Kenya KEYWORDS Button Mushrooms. Synthetic Composts. Key Factors. Microorganisms Growth ABSTRACT Button mushrooms, Agaricus sp. are secondary decomposers that require nutritious and very selective composts for their growth. Selectivity of these composts is influenced by both biological and physico-chemical characteristics of composting process. The conventional method of preparing button mushroom composts is to use a combination of horse manure, hay and a high nitrogenous source such as chicken manure. These materials are composted over time until the compost is ‘mature’. In the absence of the materials above, several alternatives can be used. An experiment was designed to use locally available materials in making two synthetic composts of grass and maize stalk. The objective was to find out factors that contribute to making compost that give high yields of button mushrooms. Three strains of mushrooms A. bisporus, A. brunescence and A. bitorquis were planted in three different composts; horse manure was used as control, maize and grass as synthetic in a complete randomized design. Nitrogen content of each compost was calculated, moisture content and temperature of the compost were recorded throughout composting and during conditioning period. Yields of mushrooms were taken in three different flushes. -

Nutritional Value of Wild Mushrooms from Kharan District of Balochistan, Pakistan

MANZOOR ET AL (2019), FUUAST J.BIOL., 9(2): 209-214 NUTRITIONAL VALUE OF WILD MUSHROOMS FROM KHARAN DISTRICT OF BALOCHISTAN, PAKISTAN. MADIHA MANZOOR, MUDASSIR ASRAR, SAAD ULLAH KHAN LEGHARI AND ZAHOOR AHMED Department of botany, university of balochistan, quetta, pakistan. Corresponding author’s email: [email protected]. الخہص زری قیقحت 18-2017دورانولباتسچنےکعلضدشہرشماخرانےسعمج دشہ رشموزم اک الہپ اطمہعل ےہ۔ وعیس امیپےن رپ علض رھب ںیم رسوے دقعنم ےئک ےئگ اتہک رشموزم وک فلتخماقمامترپالتشایکاجےکس۔رشمومیکاپچن فلتخم ااسقم وممس اہبر ےس وممس رگام ےک دوران عمج یک ںیئگ نج اک قلعت دوژین Basidiomycota اور Agaricomycetes اور ڈر Agaricales اور Family Agaricaceae ےس Agaricus bisporus, Coprinus, comatus, copruis sterquilinus Sprecies ,Agaricus bitorquis اور Coprinellus micaceus اکقلعت یلمیف Psathyreaceaeےسےہ۔انیکذغایئ ازجاء اک زجتہی ایک ایگ اھت، یمن یک دقمار %88.8 ےس %91.1 کتیھت۔ بس ےس زایدہ یمن Agaricus bitorquis ںیم راکیرڈ یک یئگ۔ Ash content %9.9 ےس %11.2 کت یھت۔ بس ےس زایدہ پ C, micacues 11.2% ںیم یلم۔ بس رشموزمںیمرپونیٹ یک دقمار افدئہ دنم ےہ، رشموزم ںیم ڈیلز/ رچیب یک دقمار %18 ےس %28 اپیئ یئگ۔ بس ےس زایدہ لڈز پ پ پ پ Agaricus bitorquis میں %28 اپای ایگ اس ںیم لڈز یک دقمار افدئہ دنم ےہ۔ فی coprius sterquilinus 2.0 ںیم راکیرڈ یک یئگ۔ فی ، رپونیٹ اور لڈز یک تبسن تہب مکاپای ایگ۔امتم رشموم ںیم وارف دقمار ںیم Mineral اپایایگ، بس ےس زایدہ میشلیک Ca(%7.4) وپاٹمیش Agaricus bisporus (15%)K اور میشینگیم م سییلسی ی Agaricus bitroquis (7.2%)Mg ںیمریغ ومعمیل وطر رپ MN ییکیی یز ، زکن Zn، ین یم Se یھب اپای ایگ۔ اتمہ ہی ااسنین زدنیگ کییلن فے اجزئ دحود ںیم اپای ایگ ذری رظن قیقحت پ ٹن ےس اثتب وہا ہک ونصمیئ وطر رپ انبیئ یئگ اوشنراہیئ رپونیٹ اور رپو ییکس رپونیٹ سپلیمسٹن ےکاقمےلبںیم رشموزم یک زغاتیئ ربارب اپیئ یئگ Abstract This is the first study of wild mushrooms collected from Kharan district of Balochistan, Pakistan during 2017- 18. -

Lecanicillium Fungicola: Causal Agent of Dry Bubble Disease in White-Button Mushroom

MOLECULAR PLANT PATHOLOGY (2010) 11(5), 585–595 DOI: 10.1111/J.1364-3703.2010.00627.X Pathogen profile Lecanicillium fungicola: causal agent of dry bubble disease in white-button mushroom ROELAND L. BERENDSEN1,*, JOHAN J. P. BAARS2, STEFANIE I. C. KALKHOVE3, LUIS G. LUGONES3, HAN A. B. WÖSTEN3 AND PETER A. H. M. BAKKER1 1Plant–Microbe Interactions, Department of Biology, Utrecht University, Padualaan 8, 3584CH Utrecht, The Netherlands 2Plant Breeding, Plant Research International, Droevendaalsesteeg 1, 6708PB Wageningen, The Netherlands 3Molecular Microbiology, Department of Biology, Utrecht University, Padualaan 8, 3584CH Utrecht, The Netherlands producer of white-button mushrooms in the world, little is SUMMARY known in the international literature about the impact of dry Lecanicillium fungicola causes dry bubble disease in commer- bubble disease in this region. cially cultivated mushroom. This review summarizes current Control: The control of L. fungicola relies on strict hygiene and knowledge on the biology of the pathogen and the interaction the use of fungicides. Few chemicals can be used for the control between the pathogen and its most important host, the white- of dry bubble because the host is also sensitive to fungicides. button mushroom, Agaricus bisporus. The ecology of the patho- Notably, the development of resistance of L. fungicola has been gen is discussed with emphasis on host range, dispersal and reported against the fungicides that are used to control dry primary source of infection. In addition, current knowledge on bubble disease. In addition, some of these fungicides may be mushroom defence mechanisms is reviewed. banned in the near future. Taxonomy: Lecanicillium fungicola (Preuss) Zare and Gams: Useful websites: http://www.mycobank.org; http://www.