William Jencks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biochemistry and the Genomic Revolution 1.1

Dedication About the authors Preface Tools and Techniques Clinical Applications Molecular Evolution Supplements Supporting Biochemistry, Fifth Edition Acknowledgments I. The Molecular Design of Life 1. Prelude: Biochemistry and the Genomic Revolution 1.1. DNA Illustrates the Relation between Form and Function 1.2. Biochemical Unity Underlies Biological Diversity 1.3. Chemical Bonds in Biochemistry 1.4. Biochemistry and Human Biology Appendix: Depicting Molecular Structures 2. Biochemical Evolution 2.1. Key Organic Molecules Are Used by Living Systems 2.2. Evolution Requires Reproduction, Variation, and Selective Pressure 2.3. Energy Transformations Are Necessary to Sustain Living Systems 2.4. Cells Can Respond to Changes in Their Environments Summary Problems Selected Readings 3. Protein Structure and Function 3.1. Proteins Are Built from a Repertoire of 20 Amino Acids 3.2. Primary Structure: Amino Acids Are Linked by Peptide Bonds to Form Polypeptide Chains 3.3. Secondary Structure: Polypeptide Chains Can Fold Into Regular Structures Such as the Alpha Helix, the Beta Sheet, and Turns and Loops 3.4. Tertiary Structure: Water-Soluble Proteins Fold Into Compact Structures with Nonpolar Cores 3.5. Quaternary Structure: Polypeptide Chains Can Assemble Into Multisubunit Structures 3.6. The Amino Acid Sequence of a Protein Determines Its Three-Dimensional Structure Summary Appendix: Acid-Base Concepts Problems Selected Readings 4. Exploring Proteins 4.1. The Purification of Proteins Is an Essential First Step in Understanding Their Function 4.2. Amino Acid Sequences Can Be Determined by Automated Edman Degradation 4.3. Immunology Provides Important Techniques with Which to Investigate Proteins 4.4. Peptides Can Be Synthesized by Automated Solid-Phase Methods 4.5. -

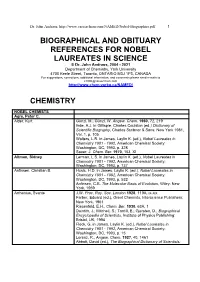

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

Antibodies with Some Bite Antibodies Have Yet to Be Determined, It Is Reasonable to Suppose That the Ester Or David E

-~-------------------------------------N8NSANDVIEWS----------------_N_A_TU_R_E_V-O_L_._32_5_22_J_A_N_U_A_RY__ 19~87 Enzyme catalysis kinetics and is subject to competitive inhibition. Although the detailed chemical mechanisms of these catalytic Antibodies with some bite antibodies have yet to be determined, it is reasonable to suppose that the ester or David E. Hansen carbamate is strained towards a tetra hedral geometry on binding, thus facilitat THE spectacular specificities and rate William Jencks', more directly, stated in ing the attack of the hydroxide ion. Fur enhancements of enzymes are without 1969 thermore, the Scripps group has already equal among all known catalysts. It is no If complementarity between active site and found that their antibody can act via both wonder then that the design of new en transition state contributes significantly to nucleophilic and general base catalysis, zymes has long been a goal of biochemists. enzyme catalysis, it should be possible to syn depending on the substrate used. Now two independent groups, one led by thesize an enzyme by constructing a binding The fact that this approach succeeded at Alfonso Tramontano and Richard Lerner site. One way to do this is to prepare an anti all gives great hope to those attempting to of the Scripps Clinic and Research Foun body to a haptenic group which resembles the isolate even more efficient antibody cat dation', and the other by Peter Schultz of transition state of a given reaction. The com alysts by this and by other strategies. In the University of California at Berkeley\ bining sites of such antibodies should be com addition, it may be possible to modify have taken steps towards this goal by plementary to the transition state and should cause an acceleration by forcing bound sub existing catalytic antibodies. -

Subject Categories

Subject Categories Click on a Subject Category below: Anthropology Archaeology Astronomy and Astrophysics Atmospheric Sciences and Oceanography Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Business and Finance Cellular and Developmental Biology and Genetics Chemistry Communications, Journalism, Editing, and Publishing Computer Sciences and Technology Economics Educational, Scientific, Cultural, and Philanthropic Administration (Nongovernmental) Engineering and Technology Geology and Mineralogy Geophysics, Geography, and Other Earth Sciences History Law and Jurisprudence Literary Scholarship and Criticism and Language Literature (Creative Writing) Mathematics and Statistics Medicine and Health Microbiology and Immunology Natural History and Ecology; Evolutionary and Population Biology Neurosciences, Cognitive Sciences, and Behavioral Biology Performing Arts and Music – Criticism and Practice Philosophy Physics Physiology and Pharmacology Plant Sciences Political Science / International Relations Psychology / Education Public Affairs, Administration, and Policy (Governmental and Intergovernmental) Sociology / Demography Theology and Ministerial Practice Visual Arts, Art History, and Architecture Zoology Subject Categories of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 1780–2019 Das, Veena Gellner, Ernest Andre Leach, Edmund Ronald Anthropology Davis, Allison (William Gluckman, Max (Herman Leakey, Mary Douglas Allison) Max) Nicol Adams, Robert Descola, Philippe Goddard, Pliny Earle Leakey, Richard Erskine McCormick DeVore, Irven (Boyd Goodenough, Ward Hunt Frere Adler-Lomnitz, Larissa Irven) Goody, John Rankine Lee, Richard Borshay Appadurai, Arjun Dillehay, Tom D. Grayson, Donald K. LeVine, Robert Alan Bailey, Frederick George Dixon, Roland Burrage Greenberg, Joseph Levi-Strauss, Claude Barth, Fredrik Dodge, Ernest Stanley Harold Levy, Robert Isaac Bateson, Gregory Donnan, Christopher B. Greenhouse, Carol J. Levy, Thomas Evan Beall, Cynthia M. Douglas, Mary Margaret Grove, David C. Lewis, Oscar Benedict, Ruth Fulton Du Bois, Cora Alice Gumperz, John J. -

President's Report 2018

VISION COUNTING UP TO 50 President's Report 2018 Chairman’s Message 4 President’s Message 5 Senior Administration 6 BGU by the Numbers 8 Building BGU 14 Innovation for the Startup Nation 16 New & Noteworthy 20 From BGU to the World 40 President's Report Alumni Community 42 2018 Campus Life 46 Community Outreach 52 Recognizing Our Friends 57 Honorary Degrees 88 Board of Governors 93 Associates Organizations 96 BGU Nation Celebrate BGU’s role in the Israeli miracle Nurturing the Negev 12 Forging the Hi-Tech Nation 18 A Passion for Research 24 Harnessing the Desert 30 Defending the Nation 36 The Beer-Sheva Spirit 44 Cultivating Israeli Society 50 Produced by the Department of Publications and Media Relations Osnat Eitan, Director In coordination with the Department of Donor and Associates Affairs Jill Ben-Dor, Director Editor Elana Chipman Editorial Staff Ehud Zion Waldoks, Jacqueline Watson-Alloun, Angie Zamir Production Noa Fisherman Photos Dani Machlis Concept and Design www.Image2u.co.il 4 President's Report 2018 Ben-Gurion University of the Negev - BGU Nation 5 From the From the Chairman President Israel’s first Prime Minister, David Ben–Gurion, said:“Only Apartments Program, it is worth noting that there are 73 This year we are celebrating Israel’s 70th anniversary and Program has been studied and reproduced around through a united effort by the State … by a people ready “Open Apartments” in Beer-Sheva’s neighborhoods, where acknowledging our contributions to the State of Israel, the the world and our students are an inspiration to their for a great voluntary effort, by a youth bold in spirit and students live and actively engage with the local community Negev, and the world, even as we count up to our own neighbors, encouraging them and helping them strive for a inspired by creative heroism, by scientists liberated from the through various cultural and educational activities. -

Thermodynamic and Extrathermodynamic Requirements of Enzyme Catalysis

Biophysical Chemistry 105 (2003) 559–572 Thermodynamic and extrathermodynamic requirements of enzyme catalysis Richard Wolfenden* Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7260, USA Received 24 October 2002; received in revised form 22 January 2003; accepted 22 January 2003 Abstract An enzyme’s affinity for the altered substrate in the transition state (symbolized here as S‡) matches the value of kcatyK m divided by the rate constant for the uncatalyzed reaction in water. The validity of this relationship is not affected by the detailed mechanism by which any particular enzyme may act, or on whether changes in enzyme conformation occur on the path to the transition state. It subsumes potential effects of substrate desolvation, H- bonding and other polar attractions, and the juxtaposition of several substrates in a configuration appropriate for reaction. The startling rate enhancements that some enzymes produce have only recently been recognized. Direct measurements of the binding affinities of stable transition-state analog inhibitors confirm the remarkable power of binding discrimination of enzymes. Several parts of the enzyme and substrate, that contribute to S‡ binding, exhibit extremely large connectivity effects, with effective relative concentrations in excess of 108 M. Exact structures of enzyme complexes with transition-state analogs also indicate a general tendency of enzyme active sites to close around S‡ in such a way as to maximize binding contacts. The role of solvent water in these binding equilibria, for which Walter Kauzmann provided a primer, is only beginning to be appreciated. ᮊ 2003 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. -

June 06 Obit.Indd

Cecile M. Pickart 1954–2006 On April 5 2006, Cecile Pickart, an outstanding biochemist, died follow- ing a protracted battle with kidney cancer. She was only fifty-one years old. The biomedical research community has lost a superb scientist, valued colleague and dear friend. A memorial celebrating Cecile’s life and scientific contributions is being planned for July 21 this year at the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University. Cecile had been a leading investigator in the ubiquitin field from its infancy and she continued to make some of the most seminal discover- ies in the field until her death — a point where the field had matured into an enterprise involving thousands of researchers around the world. Photo courtesy of the Bloomberg School of Public Health, John Hopkins University After graduating summa cum laude in 1976 with a B.S. degree in biology from Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina, Cecile earned These polyubiquitin chains were used for the first structural studies of a Ph.D. in biochemistry from Brandeis University. There, she cut her ubiquitin polymers, allowing Cecile and her colleagues to identify key teeth in enzymology under the tutelage of one of the premier enzymolo- residues on the ubiquitin surface that participate in proteasome binding gists of the day, William Jencks. In 1982, she left to study with another and other ubiquitin functions. She then worked out a method to attach renowned enzymologist, Irwin Rose, at the Fox Chase Cancer Center in these chains to substrate proteins. This beautiful work culminated in a Philadelphia, where she began her studies on ubiquitin. -

V5716 J Flc `,Strc1%Ttnn

N.A.C.A0 BULLETIN V5716 J��flC�`,strc1%tTnN LI BRA R the New Spring Regionals to Take Place at Philadelphia and Lansing 795 Annual Conference Committees Start Their Work 798 Picture Post - Scripts to San Francisco Regional 799 Research Project Committee Appointed 803 Oklahoma City Newest N.A.C.A. Chapter 807 In the Public Eye 801 Congratulations To 805 Chapter Competition 809 V � Chapter Meetings 810 a* N.A.C.A. BULLETIN VolumeXXXV11, Number p o. Published by NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF COST ACCOUNTANTS 505 PARK AvE., NEW YORK 22, N. Y. BULLETIN BOARD HAVE YOU CONSIDERED . N.A.C.A. Accounting Practice Reports for use in Education of Accounting Personnel Within Your Company? TWO REPORTS NOW AVAILABLE . Controlling and Accounting for Supplies Planning, Controlling and Accounting for Maintenance These reports summarize current practice and indicate many ways in which accounting in these areas has been effectively carried out. Single Copies 8.25 each Orders for 10 or more 96.20 eadi This Baflstin is published monthly by the National Association of Cost Accountants, 505 Park Ave., New York 22, N. Y. Subscription price, $10 per year. Reentered as second -class matter September 22, 1949, at the Post Office, New York, N. Y., under the Act of March 3, 1879. N.A.C.A. BULLETIN, Vol. XXXVII, No. 6, February, 1956 COPYRIGHT 1956 BY THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF COST ACCOUNTANTS _ 1 1 " 1 ice.. 9FIT Spring Regionals to Take Place at Philadephia and Lansing N SPITE OF intervening weeks — and trial accountant's hand in meeting his Iweather — Spring lies not so far challenge. -

Hydrogen Bonding in the Ketosteroid Isomerase Oxyanion Hole

PLoS BIOLOGY Testing Electrostatic Complementarity in Enzyme Catalysis: Hydrogen Bonding in the Ketosteroid Isomerase Oxyanion Hole Daniel A. Kraut1, Paul A. Sigala1, Brandon Pybus2, Corey W. Liu3, Dagmar Ringe2, Gregory A. Petsko2, Daniel Herschlag1* 1 Department of Biochemistry, Stanford University, Stanford, California, United States of America, 2 Department of Biochemistry, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States of America, 3 Stanford Magnetic Resonance Laboratory, Stanford University, Stanford, California, United States of America A longstanding proposal in enzymology is that enzymes are electrostatically and geometrically complementary to the transition states of the reactions they catalyze and that this complementarity contributes to catalysis. Experimental evaluation of this contribution, however, has been difficult. We have systematically dissected the potential contribution to catalysis from electrostatic complementarity in ketosteroid isomerase. Phenolates, analogs of the transition state and reaction intermediate, bind and accept two hydrogen bonds in an active site oxyanion hole. The binding of substituted phenolates of constant molecular shape but increasing pKa models the charge accumulation in the oxyanion hole during the enzymatic reaction. As charge localization increases, the NMR chemical shifts of protons involved in oxyanion hole hydrogen bonds increase by 0.50–0.76 ppm/pKa unit, suggesting a bond shortening of ;0.02 A˚/pKa unit. Nevertheless, there is little change in binding affinity across a series of substituted phenolates (DDG ¼0.2 kcal/mol/pKa unit). The small effect of increased charge localization on affinity occurs despite the shortening of the hydrogen bonds and a large favorable change in binding enthalpy (DDH ¼2.0 kcal/mol/pKa unit). This shallow dependence of binding affinity suggests that electrostatic complementarity in the oxyanion hole makes at most a modest contribution to catalysis of ;300-fold. -

Threat Vision

THREAT VISION ANNUAL REPORT 2003 You may notice that this year’s annual report is longer than usual. This is due to the fact that it represents 17 months, rather than 12, as we have changed our donor reporting to coincide with the calendar year. Our next report will come out in spring 2005 and we anticipate it will be back to its usual size. We encourage you to visit our website for the most up-to-date information about our work: www.earthjustice.org. Cover Photograph: “Mesa Arch” by Bruce Dale A window in the sky at Canyonlands National Park, Utah, the Mesa Arch stands some 2,000 feet above the Green and Colorado rivers. page 3 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AND CHAIR . .2 Roadless . .3 Energy . .4 Air . .5 Endangered Species . .6 Judging the Environment . .7 CLIENTS . .8 PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS . .13 Bozeman, MT . .14 Denver, CO . .16 Honolulu, HI . .18 Juneau, AK . .20 Oakland, CA . .22 Seattle, WA . .24 Tallahassee, FL . .26 Washington, DC . .28 International . .30 Environmental Law Clinic at Stanford University . .32 POLICY & LEGISLATION . .34 COMMUNICATIONS . .36 FINANCIAL REPORT Management’s Analysis . .38 Statements of Position . .40 Statements of Activities and Changes . .41 CONTRIBUTORS . .42 PAUL BOWER MEMORIAL . .63 GIVING OPPORTUNITIES . .64 HEADQUARTERS STAFF . .66 BOARD OF TRUSTEES . .67 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AND CHAIR While the year 2003 was not, by any measure, a good year for the environment, Earthjustice has continued to anticipate changing times by developing new and creative ways to defend the laws that protect our natural heritage and health. -

General Kofi A. Annan the United Nations United Nations Plaza

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS O2 1 39 October 10, 1997 HENRY W. KENDALL ROOM 2.4-51 4 (617) 253-7584 JULIUS A. STRATTON PROFESSOR OF PHYSICS Secretary- General Kofi A. Annan The United Nations United Nations Plaza . ..\ U New York City NY Dear Mr. Secretary-General: I have received your letter of October 1 , which you sent to me and my fellow Nobel laureates, inquiring whetHeTrwould, from time to time, provide advice and ideas so as to aid your organization in becoming more effective and responsive in its global tasks. I am grateful to be asked to support you and the United Nations for the contributions you can make to resolving the problems that now face the world are great ones. I would be pleased to help in whatever ways that I can. ~~ I have been involved in many of the issues that you deal with for many years, both as Chairman of the Union of Concerne., Scientists and, more recently, as an advisor to the World Bank. On several occasions I have participated in or initiated activities that brought together numbers of Nobel laureates to lend their voices in support of important international changes. -* . I include several examples of such activities: copies of documents, stemming from the . r work, that set out our views. I initiated the World Bank and the Union of Concerned Scientists' examples but responded to President Clinton's Round Table initiative. Again, my appreciation for your request;' I look forward to opportunities to contribute usefully. Sincerely yours ; Henry; W. -

RWJ Medicine • Spring 2019

A PUBLICATION FOR ALUMNI & FRIENDS OF RUTGERS ROBERT WOOD JOHNSON MEDICAL SCHOOL SUMMER • 2019 S f f Social Media HIGHLIGHTS FOLLOW US on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter for News about the Medical School in Real Time! rwjms RWJMS RWJMedicalschool @vishrajmd RWJMS rwjms @RWJMS doc.meesh Don’t forget to tag #RWJMS when you post! We want to see what you’re up to! LETTER FROM THE DEAN Dear Friends, am delighted to serve as interim dean of Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School and have the opportunity to lead the school as we enter the second year of the RWJBarnabas Health–Rutgers IUniversity partnership, offering expanded patient care and educational opportunities. On a personal level, I am working with a distinguished faculty who have been friends and colleagues throughout my 14 years leading Rutgers New Jersey Medical School. This issue of Robert Wood Johnson Medicine highlights people at this school who make academic med- icine so exciting as, together, we pursue continued success in our commitment to providing great care to every patient. Our cover article, “TeamSTEPPS: Student-Led Teamwork Training Focuses on Patient Safety” (page 17), underscores the importance of student-led initiatives. Piloted by two student-veterans, the project is fulfilling our vision of teaching strong teamwork skills to reduce medical risk and improve patient outcomes. We turn to the career of Stephen R. Brant, MD, professor of medicine and chief, division of gastroenterol- ogy and hepatology (“Sails Up,” page 27). Dr. Brant identified key regulators of inflammatory bowel disease and later expanded research into afflicted but unstudied populations.