Hydrogen Bonding in the Ketosteroid Isomerase Oxyanion Hole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Structure of SARS-Cov-2 Main Protease in the Apo State Reveals the 2 Inactive Conformation 3

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.12.092171; this version posted May 13, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease in the apo state reveals the 2 inactive conformation 3 4 Xuelan Zhoua,1, Fangling Zhongb,c,1, Cheng Lind,e, Xiaohui Hua, Yan Zhangf, Bing Xiongg, 5 Xiushan Yinh,i, Jinheng Fuj, Wei Heb, Jingjing Duank, Yang Ful, Huan Zhoum, Qisheng Wang 6 m,*, Jian Li b,c,*, Jin Zhanga,* 7 8 a School of Basic Medical Sciences, Nanchang University, Nanchang, Jiangxi, 330031, China. 9 b College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Gannan Medical University, Ganzhou, 341000, Jiangxi, 10 PR, China. 11 c Laboratory of Prevention and treatment of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, 12 Ministry of Education, Gannan Medical University, Ganzhou 341000, PR China 13 d Shenzhen Crystalo Biopharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Shenzhen, Guangdong, 518118, China 14 e Jiangxi Jmerry Biopharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Ganzhou, Jiangxi, 341000, China. 15 f The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang, Jiangxi, 330031, China 16 g Department of Medicinal Chemistry, Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese 17 Academy of Sciences, 555 Zuchongzhi Road , Shanghai 201203 , China. 18 h Applied Biology Laboratory, Shenyang University of Chemical Technology, 110142, 19 Shenyang, China 20 i Biotech & Biomedicine Science (Jiangxi)Co. Ltd, Ganzhou, 341000, China 21 j Jiangxi-OAI Joint -

Biochemistry and the Genomic Revolution 1.1

Dedication About the authors Preface Tools and Techniques Clinical Applications Molecular Evolution Supplements Supporting Biochemistry, Fifth Edition Acknowledgments I. The Molecular Design of Life 1. Prelude: Biochemistry and the Genomic Revolution 1.1. DNA Illustrates the Relation between Form and Function 1.2. Biochemical Unity Underlies Biological Diversity 1.3. Chemical Bonds in Biochemistry 1.4. Biochemistry and Human Biology Appendix: Depicting Molecular Structures 2. Biochemical Evolution 2.1. Key Organic Molecules Are Used by Living Systems 2.2. Evolution Requires Reproduction, Variation, and Selective Pressure 2.3. Energy Transformations Are Necessary to Sustain Living Systems 2.4. Cells Can Respond to Changes in Their Environments Summary Problems Selected Readings 3. Protein Structure and Function 3.1. Proteins Are Built from a Repertoire of 20 Amino Acids 3.2. Primary Structure: Amino Acids Are Linked by Peptide Bonds to Form Polypeptide Chains 3.3. Secondary Structure: Polypeptide Chains Can Fold Into Regular Structures Such as the Alpha Helix, the Beta Sheet, and Turns and Loops 3.4. Tertiary Structure: Water-Soluble Proteins Fold Into Compact Structures with Nonpolar Cores 3.5. Quaternary Structure: Polypeptide Chains Can Assemble Into Multisubunit Structures 3.6. The Amino Acid Sequence of a Protein Determines Its Three-Dimensional Structure Summary Appendix: Acid-Base Concepts Problems Selected Readings 4. Exploring Proteins 4.1. The Purification of Proteins Is an Essential First Step in Understanding Their Function 4.2. Amino Acid Sequences Can Be Determined by Automated Edman Degradation 4.3. Immunology Provides Important Techniques with Which to Investigate Proteins 4.4. Peptides Can Be Synthesized by Automated Solid-Phase Methods 4.5. -

Naming Polyatomic Ions and Acids Oxyanions

Oxyanions Naming Polyatomic Ions and Oxyanions Acids Oxyanions- negative ions containing Oxyanions may contain the prefix oxygen. “hypo-”, less than, or “per-”, more than. These have the suffix “-ate” or “-ite” For example - “-ate” means it has more oxygen atoms ClO4 Perchlorate bonded, “-ite” has less - ClO3 Chlorate For example - ClO2 Chlorite 2- SO4 sulfate ClO- Hypochlorite 2- SO3 sulfite Acids Naming acids Naming Acids Certain compounds produce H+ ions in Does it contain oxygen? water, these are called acids. If it does not, it gets the prefix “hydro-” and If it does contain an oxyanion, then the suffix “-ic acid” replace the ending. You can recognize them because the neutral compound starts with “H”. HCl If the ending was “–ate”, add “-ic acid” Hydrochloric acid If the ending was “–ite”, add “-ous acid” For example HCl, H2SO4, and HNO3. HF Don’t confuse a polyatomic ion with a H2SO4 Sulfuric Acid Hydrofluoric acid neutral compound. H2SO3 Sulfurous Acid HCN HCO - is hydrogen carbonate, not an acid. 3 Hydrocyanic acid Examples Examples Nomenclature (naming) of Covalent compounds HNO3 HNO3 Nitric Acid HI HI Hydroiodic acid H3AsO4 H3AsO4 Arsenic Acid HClO2 HClO2 Chlorous Acid 1 Determining the type of bond Covalent bonding is very Covalent bonding is very First, determine if you have an ionic different from ionic naming compound or a covalent compound. similar to ionic naming A metal and a nonmetal will form an You always name the one that is least Ionic names ignored the subscript ionic bond. electronegative first (furthest from because there was only one possible Compounds with Polyatomic ions form fluorine) ratio of elements. -

Mechanistic Insights Into the Inhibition of Prostate Specific Antigen by [Beta

proteins STRUCTURE O FUNCTION O BIOINFORMATICS Mechanistic insights into the inhibition of prostate specific antigen by b-lactam class compounds Pratap Singh,1,2* Simon A. Williams,2 Meha H. Shah,3 Thomas Lectka,3 Gareth J. Pritchard,4 John T. Isaacs,2 and Samuel R. Denmeade1,2 1 Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Whiting School of Engineering, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland 21218 2 Chemical Therapeutics Program, The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland 21231 3 Department of Chemistry, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland 21218 4 Department of Chemistry, Loughborough University, Loughborough, Leicestershire LE11 3TU, United Kingdom ABSTRACT for the effect of stereochemistry of the lactam ring on the in- hibitory potency was elucidated through docking of b-lactam Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) is a biomarker used in the enantiomers. As a validation of our docking methodology, diagnosis of prostate cancer and to monitor therapeutic two novel enantiomers were synthesized and evaluated for response. However, its precise role in prostate carcinogenesis their inhibitory potency using fluorogenic substrate based ac- and metastasis remains largely unknown. A number of stud- tivity assays. Additionally, cis enantiomers of eight b-lactam ies arguing in the favor of an active role of PSA in prostate compounds reported in a previous study were docked and cancer development and progression have implicated this their GOLD scores -

Determining the Catalytic Role of Remote Substrate Binding Interactions in Ketosteroid Isomerase

Determining the catalytic role of remote substrate binding interactions in ketosteroid isomerase Jason P. Schwans1, Daniel A. Kraut1, and Daniel Herschlag2 Department of Biochemistry, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305 Edited by Vern L. Schramm, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, and approved June 24, 2009 (received for review February 2, 2009) A fundamental difference between enzymes and small chemical with substrate binding solvent is displaced and excluded from the catalysts is the ability of enzymes to use binding interactions with active site and solvent exclusion may be important in shaping the nonreactive portions of substrates to accelerate chemical reactions. electrostatic environment within the active site (26, 27). Indeed, Remote binding interactions can localize substrates to the active solvent exclusion by substrate binding has been suggested to be site, position substrates relative to enzymatic functional groups important for catalysis in numerous enzymes (e.g., refs. 26–32). and other substrates, trigger conformational changes, induce local Jencks and others realized that remote binding interactions destabilization, and modulate an active site environment by sol- can do more than provide for tight binding between substrate vent exclusion. We investigated the role of remote substrate and enzyme. Reactions of bound substrates can be facilitated by binding interactions in the reaction catalyzed by the enzyme use of so-called ‘‘intrinsic binding energy’’, which can pay for ketosteroid isomerase (KSI), which catalyzes a double bond migra- substrate desolvation, distortion, electrostatic destabilization, tion of steroid substrates through a dienolate intermediate that is and entropy loss (3, 7, 33, 34). The term intrinsic binding energy stabilized in an oxyanion hole. -

Part I Principles of Enzyme Catalysis

j1 Part I Principles of Enzyme Catalysis Enzyme Catalysis in Organic Synthesis, Third Edition. Edited by Karlheinz Drauz, Harald Groger,€ and Oliver May. Ó 2012 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. Published 2012 by Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. j3 1 Introduction – Principles and Historical Landmarks of Enzyme Catalysis in Organic Synthesis Harald Gr€oger and Yasuhisa Asano 1.1 General Remarks Enzyme catalysis in organic synthesis – behind this term stands a technology that today is widely recognized as a first choice opportunity in the preparation of a wide range of chemical compounds. Notably, this is true not only for academic syntheses but also for industrial-scale applications [1]. For numerous molecules the synthetic routes based on enzyme catalysis have turned out to be competitive (and often superior!) compared with classic chemicalaswellaschemocatalyticsynthetic approaches. Thus, enzymatic catalysis is increasingly recognized by organic chemists in both academia and industry as an attractive synthetic tool besides the traditional organic disciplines such as classic synthesis, metal catalysis, and organocatalysis [2]. By means of enzymes a broad range of transformations relevant in organic chemistry can be catalyzed, including, for example, redox reactions, carbon–carbon bond forming reactions, and hydrolytic reactions. Nonetheless, for a long time enzyme catalysis was not realized as a first choice option in organic synthesis. Organic chemists did not use enzymes as catalysts for their envisioned syntheses because of observed (or assumed) disadvantages such as narrow substrate range, limited stability of enzymes under organic reaction conditions, low efficiency when using wild-type strains, and diluted substrate and product solutions, thus leading to non-satisfactory volumetric productivities. -

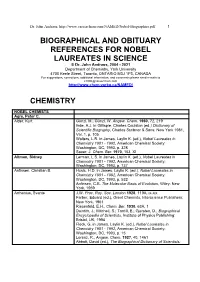

Biographical References for Nobel Laureates

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Nobel-Biographies.pdf 1 BIOGRAPHICAL AND OBITUARY REFERENCES FOR NOBEL LAUREATES IN SCIENCE © Dr. John Andraos, 2004 - 2021 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ CHEMISTRY NOBEL CHEMISTS Agre, Peter C. Alder, Kurt Günzl, M.; Günzl, W. Angew. Chem. 1960, 72, 219 Ihde, A.J. in Gillispie, Charles Coulston (ed.) Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Charles Scribner & Sons: New York 1981, Vol. 1, p. 105 Walters, L.R. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 328 Sauer, J. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, XI Altman, Sidney Lerman, L.S. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 737 Anfinsen, Christian B. Husic, H.D. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 532 Anfinsen, C.B. The Molecular Basis of Evolution, Wiley: New York, 1959 Arrhenius, Svante J.W. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 1928, 119A, ix-xix Farber, Eduard (ed.), Great Chemists, Interscience Publishers: New York, 1961 Riesenfeld, E.H., Chem. Ber. 1930, 63A, 1 Daintith, J.; Mitchell, S.; Tootill, E.; Gjersten, D., Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists, Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 1994 Fleck, G. in James, Laylin K. (ed.), Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 1901 - 1992, American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1993, p. 15 Lorenz, R., Angew. -

And Inter-Protein Couplings of Backbone Motions Underlie

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Intra- and inter-protein couplings of backbone motions underlie protein thiol-disulfde exchange cascade Received: 26 July 2018 Wenbo Zhang1,3, Xiaogang Niu2,3, Jienv Ding1,3,5, Yunfei Hu2,3,6 & Changwen Jin1,2,3,4 Accepted: 6 October 2018 The thioredoxin (Trx)-coupled arsenate reductase (ArsC) is a family of enzymes that catalyzes the Published: xx xx xxxx reduction of arsenate to arsenite in the arsenic detoxifcation pathway. The catalytic cycle involves a series of relayed intramolecular and intermolecular thiol-disulfde exchange reactions. Structures at diferent reaction stages have been determined, suggesting signifcant conformational fuctuations along the reaction pathway. Herein, we use two state-of-the-art NMR methods, the chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) and the CPMG-based relaxation dispersion (CPMG RD) experiments, to probe the conformational dynamics of B. subtilis ArsC in all reaction stages, namely the enzymatic active reduced state, the intra-molecular C10–C82 disulfde-bonded intermediate state, the inactive oxidized state, and the inter-molecular disulfde-bonded protein complex with Trx. Our results reveal highly rugged energy landscapes in the active reduced state, and suggest global collective motions in both the C10–C82 disulfde-bonded intermediate and the mixed-disulfde Trx-ArsC complex. Protein thiol-disulfde exchange reactions play fundamental roles in living systems, represented by the thiore- doxin (Trx) and glutaredoxin (Grx) systems that maintain the cytoplasmic reducing environment, the protein DsbA that catalyzes the formation of protein disulfde bonds in bacterial periplasm, as well as the protein disulfde isomerase (PDI) proteins that facilitate correct disulfde bonding1–5. -

ENZYMES: Catalysis, Kinetics and Mechanisms N

ENZYMES: Catalysis, Kinetics and Mechanisms N. S. Punekar ENZYMES: Catalysis, Kinetics and Mechanisms N. S. Punekar Department of Biosciences & Bioengineering Indian Institute of Technology Bombay Mumbai, Maharashtra, India ISBN 978-981-13-0784-3 ISBN 978-981-13-0785-0 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0785-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018947307 # Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Printed on acid-free paper This Springer imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. -

Antibodies with Some Bite Antibodies Have Yet to Be Determined, It Is Reasonable to Suppose That the Ester Or David E

-~-------------------------------------N8NSANDVIEWS----------------_N_A_TU_R_E_V-O_L_._32_5_22_J_A_N_U_A_RY__ 19~87 Enzyme catalysis kinetics and is subject to competitive inhibition. Although the detailed chemical mechanisms of these catalytic Antibodies with some bite antibodies have yet to be determined, it is reasonable to suppose that the ester or David E. Hansen carbamate is strained towards a tetra hedral geometry on binding, thus facilitat THE spectacular specificities and rate William Jencks', more directly, stated in ing the attack of the hydroxide ion. Fur enhancements of enzymes are without 1969 thermore, the Scripps group has already equal among all known catalysts. It is no If complementarity between active site and found that their antibody can act via both wonder then that the design of new en transition state contributes significantly to nucleophilic and general base catalysis, zymes has long been a goal of biochemists. enzyme catalysis, it should be possible to syn depending on the substrate used. Now two independent groups, one led by thesize an enzyme by constructing a binding The fact that this approach succeeded at Alfonso Tramontano and Richard Lerner site. One way to do this is to prepare an anti all gives great hope to those attempting to of the Scripps Clinic and Research Foun body to a haptenic group which resembles the isolate even more efficient antibody cat dation', and the other by Peter Schultz of transition state of a given reaction. The com alysts by this and by other strategies. In the University of California at Berkeley\ bining sites of such antibodies should be com addition, it may be possible to modify have taken steps towards this goal by plementary to the transition state and should cause an acceleration by forcing bound sub existing catalytic antibodies. -

Evidence Against Stabilization of the Transition State Oxyanion by a Pka-Perturbed RNA Base in the Peptidyl Transferase Center

Evidence against stabilization of the transition state oxyanion by a pKa-perturbed RNA base in the peptidyl transferase center K. Mark Parnell*, Amy C. Seila†, and Scott A. Strobel*‡§ Departments of *Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry, †Genetics, and ‡Chemistry, Yale University, 260 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, CT 06520-8114 Edited by Harry F. Noller, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA, and approved July 16, 2002 (received for review April 8, 2002) The crystal structure of the ribosomal 50S subunit from Haloarcula activity, suggesting that 23S and 5S rRNA may constitute the marismortui in complex with the transition state analog CCdA- bulk of the peptidyl transferase center (8). phosphate-puromycin (CCdApPmn) led to a mechanistic proposal The most unambiguous evidence that the active site of the wherein the universally conversed A2451 in the ribosomal active ribosome is comprised of RNA came from the 2.4-Å crystal site acts as an ‘‘oxyanion hole’’ to promote the peptidyl transferase structure of the Haloarcula marismortui 50S ribosomal subunit reaction [Nissen, P., Hansen, J., Ban, N., Moore, P.B., and Steitz, T.A. reported by Ban et al. (9) and Nissen et al. (10). The structure of the (2000) Science 289, 920–929]. In the model, close proximity (3 Å) 50S subunit complexed with the transition-state analog CCdA- between the A2451 N3 and the nonbridging phosphoramidate phosphate-puromycin (CCdApPmn) was vital to this structural oxygen of CCdApPmn suggested that the carbonyl oxyanion identification. CCdApPmn includes the minimal components of formed during the tetrahedral transition state is stabilized by both peptidyl transferase substrates (11). CCdA binds the P site, and hydrogen bonding to the protonated A2451 N3, the pKa of which puromycin binds the A site (Fig. -

Substrate and Nucleotide

ClpX interactions with ClpP, SspB, protein substrate and nucleotide by OF ECHNOLOGY Greg Louis Hersch FEB 0 1RIE2006 B.S. Biochemistry LIBRAR IES University of California at Davis, 2001 Submitted to the Department of Biology in partial fulfillment of the requirementsfor the degreeof Doctor of Philosophy in Biochemistry McM0.l at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology February 2006 © 2005 Greg L. Hersch. All rights reserved The authors herebygrants to MITpermission to reproduceand to distributepublicly Paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: .1 - · -- - Department of Biology Certified by: I/ Robert T. Sauer Salvador E. Luria Professor of Biology Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: / - t R11 (_2~ ,tenhen P RPellI Professor of Biology Co-Chair, Biology Graduate Committee CIpX interactions with CIpP, SspB, protein substrate and nucleotide By Greg Louis Hersch Submitted to the Department of Biology on February 6th, 2006 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy in biochemistry ABSTRACT ClpXP and related ATP-dependent proteases are implements of cytosolic protein destruction. They couple chemical energy, derived from ATP hydrolysis, to the selection, unfolding, and degradation of protein substrates with the appropriate degradation signals. The ClpX component of ClpXP is a hexameric enzyme that recognizes protein substrates and unfolds them in an ATP-dependent reaction. Following unfolding, ClpX translocates the unfolded substrate into the ClpP peptidase for degradation. The best characterized degradation signal is the ssrA-degradation tag, which contains a binding site for ClpX and an adjacent binding site for the SspB adaptor protein. I show that the close proximity of these binding elements causes SspB binding to mask signals needed for ssrA-tag recognition by ClpX.