Enzyme Catalysis.Pptx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part I Principles of Enzyme Catalysis

j1 Part I Principles of Enzyme Catalysis Enzyme Catalysis in Organic Synthesis, Third Edition. Edited by Karlheinz Drauz, Harald Groger,€ and Oliver May. Ó 2012 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. Published 2012 by Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. j3 1 Introduction – Principles and Historical Landmarks of Enzyme Catalysis in Organic Synthesis Harald Gr€oger and Yasuhisa Asano 1.1 General Remarks Enzyme catalysis in organic synthesis – behind this term stands a technology that today is widely recognized as a first choice opportunity in the preparation of a wide range of chemical compounds. Notably, this is true not only for academic syntheses but also for industrial-scale applications [1]. For numerous molecules the synthetic routes based on enzyme catalysis have turned out to be competitive (and often superior!) compared with classic chemicalaswellaschemocatalyticsynthetic approaches. Thus, enzymatic catalysis is increasingly recognized by organic chemists in both academia and industry as an attractive synthetic tool besides the traditional organic disciplines such as classic synthesis, metal catalysis, and organocatalysis [2]. By means of enzymes a broad range of transformations relevant in organic chemistry can be catalyzed, including, for example, redox reactions, carbon–carbon bond forming reactions, and hydrolytic reactions. Nonetheless, for a long time enzyme catalysis was not realized as a first choice option in organic synthesis. Organic chemists did not use enzymes as catalysts for their envisioned syntheses because of observed (or assumed) disadvantages such as narrow substrate range, limited stability of enzymes under organic reaction conditions, low efficiency when using wild-type strains, and diluted substrate and product solutions, thus leading to non-satisfactory volumetric productivities. -

ENZYMES: Catalysis, Kinetics and Mechanisms N

ENZYMES: Catalysis, Kinetics and Mechanisms N. S. Punekar ENZYMES: Catalysis, Kinetics and Mechanisms N. S. Punekar Department of Biosciences & Bioengineering Indian Institute of Technology Bombay Mumbai, Maharashtra, India ISBN 978-981-13-0784-3 ISBN 978-981-13-0785-0 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0785-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018947307 # Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Printed on acid-free paper This Springer imprint is published by the registered company Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. -

Exploring the Chemistry and Evolution of the Isomerases

Exploring the chemistry and evolution of the isomerases Sergio Martínez Cuestaa, Syed Asad Rahmana, and Janet M. Thorntona,1 aEuropean Molecular Biology Laboratory, European Bioinformatics Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge CB10 1SD, United Kingdom Edited by Gregory A. Petsko, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, and approved January 12, 2016 (received for review May 14, 2015) Isomerization reactions are fundamental in biology, and isomers identifier serves as a bridge between biochemical data and ge- usually differ in their biological role and pharmacological effects. nomic sequences allowing the assignment of enzymatic activity to In this study, we have cataloged the isomerization reactions known genes and proteins in the functional annotation of genomes. to occur in biology using a combination of manual and computa- Isomerases represent one of the six EC classes and are subdivided tional approaches. This method provides a robust basis for compar- into six subclasses, 17 sub-subclasses, and 245 EC numbers cor- A ison and clustering of the reactions into classes. Comparing our responding to around 300 biochemical reactions (Fig. 1 ). results with the Enzyme Commission (EC) classification, the standard Although the catalytic mechanisms of isomerases have already approach to represent enzyme function on the basis of the overall been partially investigated (3, 12, 13), with the flood of new data, an integrated overview of the chemistry of isomerization in bi- chemistry of the catalyzed reaction, expands our understanding of ology is timely. This study combines manual examination of the the biochemistry of isomerization. The grouping of reactions in- chemistry and structures of isomerases with recent developments volving stereoisomerism is straightforward with two distinct types cis-trans in the automatic search and comparison of reactions. -

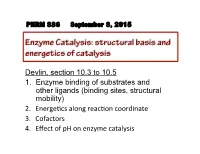

Enzyme Catalysis: Structural Basis and Energetics of Catalysis

PHRM 836 September 8, 2015 Enzyme Catalysis: structural basis and energetics of catalysis Devlin, section 10.3 to 10.5 1. Enzyme binding of substrates and other ligands (binding sites, structural mobility) 2. Energe(cs along reac(on coordinate 3. Cofactors 4. Effect of pH on enzyme catalysis Enzyme catalysis: Review Devlin sections 10.6 and 10.7 • Defini(ons of catalysis, transi(on state, ac(vaon energy • Michaelis-Menten equaon – Kine(c parameters in enzyme kine(cs (kcat, kcat/KM, Vmax, etc) – Lineweaver-Burk plot • Transi(on-state stabilizaon • Meaning of proximity, orientaon, strain, and electrostac stabilizaon in enzyme catalysis • General acid/base catalysis • Covalent catalysis 2015, September 8 PHRM 836 - Devlin Ch 10 2 Structure determines enzymatic catalysis as illustrated by this mechanism for ____ 2015, September 8 PHRM 836 - Devlin Ch 10 www.studyblue.com 3 Substrate binding by enzymes • Highly complementary interac(ons between substrate and enzyme – Hydrophobic to hydrophobic – Hydrogen bonding – Favorable Coulombic interac(ons • Substrate binding typically involves some degree of conformaonal change in the enzyme – Enzymes need to be flexible for substrate binding and catalysis. – Provides op(mal recogni(on of substrates – Brings cataly(cally important residues to the right posi(on. 2015, September 8 PHRM 836 - Devlin Ch 10 4 Substrate binding by enzymes • Highly complementary interac(ons between substrate and enzyme – Hydrophobic to hydrophobic – Hydrogen bonding – Favorable Coulombic interac(ons • Substrate binding typically involves some degree of conformaonal change in the enzyme – Enzymes need to be flexible for substrate binding and catalysis. – Provides op(mal recogni(on of substrates – Brings cataly(cally important residues to the right posi(on. -

Specificity of Trypsin and Chymotrypsin: Loop-Motion-Controlled Dynamic Correlation As a Determinant

Biophysical Journal Volume 89 August 2005 1183–1193 1183 Specificity of Trypsin and Chymotrypsin: Loop-Motion-Controlled Dynamic Correlation as a Determinant Wenzhe Ma,*y Chao Tang,*z and Luhua Lai*y *Center for Theoretical Biology, and yState Key Laboratory for Structural Chemistry of Stable and Unstable Species, College of Chemistry, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China; and zCalifornia Institute for Quantitative Biomedical Research, Departments of Biopharmaceutical Sciences and Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of California, San Francisco, California 94143-2540 ABSTRACT Trypsin and chymotrypsin are both serine proteases with high sequence and structural similarities, but with different substrate specificity. Previous experiments have demonstrated the critical role of the two loops outside the binding pocket in controlling the specificity of the two enzymes. To understand the mechanism of such a control of specificity by distant loops, we have used the Gaussian network model to study the dynamic properties of trypsin and chymotrypsin and the roles played by the two loops. A clustering method was introduced to analyze the correlated motions of residues. We have found that trypsin and chymotrypsin have distinct dynamic signatures in the two loop regions, which are in turn highly correlated with motions of certain residues in the binding pockets. Interestingly, replacing the two loops of trypsin with those of chymotrypsin changes the motion style of trypsin to chymotrypsin-like, whereas the same experimental replacement was shown necessary to make trypsin have chymotrypsin’s enzyme specificity and activity. These results suggest that the cooperative motions of the two loops and the substrate-binding sites contribute to the activity and substrate specificity of trypsin and chymotrypsin. -

Examination of Mutants That Alter Oxygen Sensitivity and Co2/O2 Substrate Specificity of the Ribulose 1,5-Bisphosphate Carboxyla

EXAMINATION OF MUTANTS THAT ALTER OXYGEN SENSITIVITY AND CO2/O2 SUBSTRATE SPECIFICITY OF THE RIBULOSE 1,5-BISPHOSPHATE CARBOXYLASE/OXYGENASE (RUBISCO) FROM ARCHAEOGLOBUS FULGIDUS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nathaniel E. Kreel, B.S. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Professor Dr. F. Robert Tabita, Advisor Approved by Professor Dr. Charles E. Bell Professor Dr. Charles L. Brooks Professor Dr. Michael Ibba ____________________________ Advisor Ohio State Biochemistry Graduate Program ABSTRACT The archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus contains a gene (rbcL2) that encodes the enzyme ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), the enzyme necessary for biological reduction and assimilation of CO2 to organic carbon. Based on sequence homologies and phylogenetic differences, archaeal Rubiscos represent a special class of Rubisco, termed form III, that distinguishes it from the previously characterized form I and form II enzymes. Form III Rubisco retains many features characteristic of all forms of Rubisco, yet exhibits many interesting and unique differences that might be exploited to learn more about structure-function relationships for this protein. For example, recombinant A. fulgidus RbcL2 was shown to possess an extremely high kcat value (23 s-1) and optimal activity was reached at temperatures up to 93°C. Furthermore, this protein was unusual in that exposure or assay in the presence of O2 (in the presence of high levels of CO2) resulted in substantial loss (90%) in activity compared to assays performed under strictly anaerobic conditions. Kinetic studies indicated that A. fulgidus RbcL2 possessed an unusually high affinity for O2. -

Intrinsic Evolutionary Constraints on Protease Structure, Enzyme

Intrinsic evolutionary constraints on protease PNAS PLUS structure, enzyme acylation, and the identity of the catalytic triad Andrew R. Buller and Craig A. Townsend1 Departments of Biophysics and Chemistry, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore MD 21218 Edited by David Baker, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, and approved January 11, 2013 (received for review December 6, 2012) The study of proteolysis lies at the heart of our understanding of enzyme evolution remain unanswered. Because evolution oper- biocatalysis, enzyme evolution, and drug development. To un- ates through random forces, rationalizing why a particular out- derstand the degree of natural variation in protease active sites, come occurs is a difficult challenge. For example, the hydroxyl we systematically evaluated simple active site features from all nucleophile of a Ser protease was swapped for the thiol of Cys at serine, cysteine and threonine proteases of independent lineage. least twice in evolutionary history (9). However, there is not This convergent evolutionary analysis revealed several interre- a single example of Thr naturally substituting for Ser in the lated and previously unrecognized relationships. The reactive protease catalytic triad, despite its greater chemical similarity rotamer of the nucleophile determines which neighboring amide (9). Instead, the Thr proteases generate their N-terminal nu- can be used in the local oxyanion hole. Each rotamer–oxyanion cleophile through a posttranslational modification: cis-autopro- hole combination limits the location of the moiety facilitating pro- teolysis (10, 11). These facts constitute clear evidence that there ton transfer and, combined together, fixes the stereochemistry of is a strong selective pressure against Thr in the catalytic triad that catalysis. -

Energetics of Enzyme Catalysis

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 75, No. 11, pp. 5250-5254, November 1978 Chemistry Energetics of enzyme catalysis (lysozyme/enzyme mechanism/dielectric effects in enzymes and in solutions/relationship between protein folding and catalysis) ARIEH WARSHEL Department of Chemistry, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 90007 Communicated by M. F. Perutz, August 2,1978 ABSTRACT Quantitative studies of the energetics of en- Beyond the macroscopic dielectric concepts zymatic reactions and the corresponding reactions in aqueous solutions indicate that charge stabilization is the most important Most theories of electrostatic interactions consider interacting energy contribution in enzyme catalysis. Low electrostatic charges as embedded in a continuum with the bulk dielectric stabilization in aqueous solutions is shown to be consistent with constant so. The application of such "continuum" theories to surprisingly large electrostatic stabilization effects in active sites the active sites of enzymes is questionable. In fact, such theories of enzymes. This is established quantitatively by comparing the cannot be used even for quantitative studies of the interaction relative stabilization of the transition states of the reaction of between ions in aqueous solutions, especially when the distance lysozyme and the corresponding reaction in aqueous solu- between interacting ions is similar to the size of the solvent tion. molecules (for discussion, see ref. 14). If charge stabilization is Enzymes are the catalysis of many biological processes. They to be studied quantitatively, the microscopic nature of the solute can accelerate the rate of chemical reactions by more than 10 solvent system must be taken in account. This can be done by orders of magnitude relative to the corresponding rates in so- the following microscopic models (5, 14). -

Optimization of the Reaction Conditions of Two Enzymes for Use in a Carbon Sequestration

Optimization of the reaction conditions of two enzymes for use in a carbon sequestration process, and investigation into immobilization via encapsulation within polymersomes by Gordon L. Nish A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Chemical Engineering Department of Chemical and Materials Engineering University of Alberta © Gordon L. Nish, 2016 ii Abstract Carbon dioxide emissions from human activities contribute to an increase of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. In nature, this gas is sequestered through the use of enzymes found in the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle, with useful molecules such as sugars being synthesized as products. A biomimetic approach to capturing carbon dioxide and using it to synthesize useful chemicals, by way of these enzymes in a bioprocess, has been proposed. To achieve this, active enzymes must be harvested and their kinetic properties need to be characterized. Optimal process conditions must be established, with an appropriate enzyme immobilization technique being applied to ameliorate the overall bioprocess. In this work, the phosphoribulokinase enzyme was produced in the bacterial cell platform Escherichia coli using molecular cloning techniques. The kinetic conditions affecting the rates of the enzymes ribose 5-phosphate isomerase A from E. coli, and phosphoribulokinase from Synechococcus elongatus, were locally optimized through surface response methodology and mathematical modeling. These models predicted the optimal pH levels, temperature, substrate concentration and other factors used in the assays. The rate of ribose 5-phosphate isomerase product formation under optimized conditions showed an increase of about 37 % over the measured rate under initial conditions, while that of phosphoribulokinase activity increased around 21 %. -

Hydrogen Bonding in the Ketosteroid Isomerase Oxyanion Hole

PLoS BIOLOGY Testing Electrostatic Complementarity in Enzyme Catalysis: Hydrogen Bonding in the Ketosteroid Isomerase Oxyanion Hole Daniel A. Kraut1, Paul A. Sigala1, Brandon Pybus2, Corey W. Liu3, Dagmar Ringe2, Gregory A. Petsko2, Daniel Herschlag1* 1 Department of Biochemistry, Stanford University, Stanford, California, United States of America, 2 Department of Biochemistry, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts, United States of America, 3 Stanford Magnetic Resonance Laboratory, Stanford University, Stanford, California, United States of America A longstanding proposal in enzymology is that enzymes are electrostatically and geometrically complementary to the transition states of the reactions they catalyze and that this complementarity contributes to catalysis. Experimental evaluation of this contribution, however, has been difficult. We have systematically dissected the potential contribution to catalysis from electrostatic complementarity in ketosteroid isomerase. Phenolates, analogs of the transition state and reaction intermediate, bind and accept two hydrogen bonds in an active site oxyanion hole. The binding of substituted phenolates of constant molecular shape but increasing pKa models the charge accumulation in the oxyanion hole during the enzymatic reaction. As charge localization increases, the NMR chemical shifts of protons involved in oxyanion hole hydrogen bonds increase by 0.50–0.76 ppm/pKa unit, suggesting a bond shortening of ;0.02 A˚/pKa unit. Nevertheless, there is little change in binding affinity across a series of substituted phenolates (DDG ¼0.2 kcal/mol/pKa unit). The small effect of increased charge localization on affinity occurs despite the shortening of the hydrogen bonds and a large favorable change in binding enthalpy (DDH ¼2.0 kcal/mol/pKa unit). This shallow dependence of binding affinity suggests that electrostatic complementarity in the oxyanion hole makes at most a modest contribution to catalysis of ;300-fold. -

The Chemistry and Evolution of Enzyme Function

The Chemistry and Evolution of Enzyme Function: Isomerases as a Case Study Sergio Mart´ınez Cuesta EMBL - European Bioinformatics Institute Gonville and Caius College University of Cambridge A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 31st July 2014 This dissertation is the result of my own work and contains nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. No part of this dissertation has been submitted or is currently being submitted for any other degree or diploma or other qualification. This thesis does not exceed the specified length limit of 60.000 words as defined by the Biology Degree Committee. This thesis has been typeset in 12pt font using LATEX according to the specifications de- fined by the Board of Graduate Studies and the Biology Degree Committee. Cambridge, 31st July 2014 Sergio Mart´ınezCuesta To my parents and my sister Contents Abstract ix Acknowledgements xi List of Figures xiii List of Tables xv List of Publications xvi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Chemistry of enzymes . .2 1.1.1 Catalytic sites, mechanisms and cofactors . .3 1.1.2 Enzyme classification . .5 1.2 Evolution of enzyme function . .6 1.3 Similarity between enzymes . .8 1.3.1 Comparing sequences and structures . .8 1.3.2 Comparing genomic context . .9 1.3.3 Comparing biochemical reactions and mechanisms . 10 1.4 Isomerases . 12 1.4.1 Metabolism . 13 1.4.2 Genome . 14 1.4.3 EC classification . 15 1.4.4 Applications . 18 1.5 Structure of the thesis . 20 2 Data Resources and Methods 21 2.1 Introduction . -

Serine Proteases Enrico Di Cera Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics, Washington University School of Medicine, Box 8231, St

IUBMB Life, 61(5): 510–515, May 2009 Critical Review Serine Proteases Enrico Di Cera Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics, Washington University School of Medicine, Box 8231, St. Louis, MO, USA the serine protease fold especially evident in the trypsins. This Summary new dimension changes our understanding of serine protease Over one third of all known proteolytic enzymes are serine function, regulation, and specificity. proteases. Among these, the trypsins underwent the most pre- dominant genetic expansion yielding the enzymes responsible for digestion, blood coagulation, fibrinolysis, development, fer- tilization, apoptosis, and immunity. The success of this expan- GENERAL PROPERTIES OF SERINE PROTEASES sion resides in a highly efficient fold that couples catalysis and Barrett and coworkers have devised a classification scheme regulatory interactions. Added complexity comes from the recent observation of a significant conformational plasticity of based on statistically significant similarities in sequence and the trypsin fold. A new paradigm emerges where two forms of structure of all known proteolytic enzymes and term this data- the protease, E* and E, are in allosteric equilibrium and deter- base MEROPS (8). The classification system divides proteases mine biological activity and specificity. Ó 2009 IUBMB into clans based on catalytic mechanism and families on the ba- IUBMB Life, 61(5): 510–515, 2009 sis of common ancestry. Over one third of all known proteolytic enzymes are serine proteases grouped into 13 clans and 40 fam- Keywords serine proteases; enzyme catalysis; thrombin; allostery. ilies. The family name stems from the nucleophilic Ser in the enzyme active site, which attacks the carbonyl moiety of the substrate peptide bond to form an acyl-enzyme intermediate (4).