Public Confidence in Social Institutions and Media Coverage: a Case of Belarus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Яюm I C R O S O F T W O R

Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) MASS MEDIA IN BELARUS 2004 ANNUAL REPORT Minsk 2005 C O N T E N T S INFRINGEMENTS OF FREEDOM OF MASS INFORMATION IN BELARUS IN 2004. REVIEW /2 STATISTICAL BACKGROUND /3 CHANGES IN THE LEGISLATION /5 INFRINGEMENTS OF RIGHTS OF MASS-MEDIA AND JOURNALISTS, CONFLICTS IN THE SPHERE OF MASS-MEDIA Criminal cases for publications in mass-media /13 Encroachments on journalists and media /16 Termination or suspension of mass-media by authorities /21 Detentions of journalists, summoning journalists to law enforcement bodies. Warnings of the Office of Public Prosecutor /29 Censorship. Interference in professional independence of editions /35 Infringements related to access to information (refusals in granting information, restrictive use of institute of accreditation) /40 The conflicts related to reception and dissemination of foreign information or activity of foreign mass-media /47 Economic policy in the sphere of mass-media /53 Restriction of the right on founding mass-media /57 Interference with production of mass-media /59 Hindrance to distribution of mass-media production /62 SENSATIONAL CASES The most significant litigations with participation of mass-media and journalists /70 Dmitry Zavadsky's case /79 Belarusian periodic printed editions mentioned in the monitoring /81 1 INFRINGEMENTS OF FREEDOM OF MASS INFORMATION IN BELARUS IN 2004. REVIEW The year 2004 for Belarus was the year of parliamentary elections and the referendum. As usual during significant political campaigns, the pressure on mass-media has increased in 2004. The deterioration of the media situation was not a temporary deviation after which everything usually comes back to normal, but represented strengthening of systematic and regular pressure upon mass- media, which continued after the election campaign. -

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

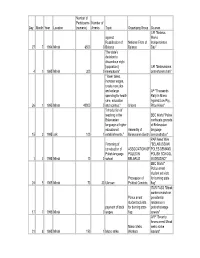

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Download Book

84 823 65 Special thanks to the Independent Institute of Socio-Economic and Political Studies for assistance in getting access to archival data. The author also expresses sincere thanks to the International Consortium "EuroBelarus" and the Belarusian Association of Journalists for information support in preparing this book. Photos by ByMedia.Net and from family albums. Aliaksandr Tamkovich Contemporary History in Faces / Aliaksandr Tamkovich. — 2014. — ... pages. The book contains political essays about people who are well known in Belarus and abroad and who had the most direct relevance to the contemporary history of Belarus over the last 15 to 20 years. The author not only recalls some biographical data but also analyses the role of each of them in the development of Belarus. And there is another very important point. The articles collected in this book were written at different times, so today some changes can be introduced to dates, facts and opinions but the author did not do this INTENTIONALLY. People are not less interested in what we thought yesterday than in what we think today. Information and Op-Ed Publication 84 823 © Aliaksandr Tamkovich, 2014 AUTHOR’S PROLOGUE Probably, it is already known to many of those who talked to the author "on tape" but I will reiterate this idea. I have two encyclopedias on my bookshelves. One was published before 1995 when many people were not in the position yet to take their place in the contemporary history of Belarus. The other one was made recently. The fi rst book was very modest and the second book was printed on classy coated paper and richly decorated with photos. -

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Article 6: Everyone has the right to recognition spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, everywhere as a person before the law. Article 7: All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimi- without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, nation to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination. Article 8: Everyone has the right to an effective rem- basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person edy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. by law. Article 9: No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security June 2011 564a Uladz Hrydzin © This report has been produced with the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). -

Straddling Russia and Europe

Straddling Russia and Europe A Compendium of Recent Jamestown Analysis on Belarus January 2013 Straddling Russia and Europe A Compendium of Recent Jamestown Analysis on Belarus Washington, D.C. January 2013 THE JAMESTOWN FOUNDATION Published in the United States by The Jamestown Foundation 1111 16th St. N.W. Suite 320 Washington, D.C. 20036 http://www.jamestown.org Copyright © The Jamestown Foundation, January 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written consent. For copyright permissions information, contact The Jamestown Foundation. The views expressed in this report are those of the contributing authors and not necessarily those of The Jamestown Foundation. For more information on this report or The Jamestown Foundation, email [email protected]. JAMESTOWN’S MISSION The Jamestown Foundation’s mission is to inform and educate policymakers and the broader policy community about events and trends in those societies, which are strategically or tactically important to the United States and which frequently restrict access to such information. Utilizing indigenous and primary sources, Jamestown’s material is delivered without political bias, filter or agenda. It is often the only source of information that should be, but is not always, available through official or intelligence channels, especially with regard to Eurasia and terrorism. Origins Launched in 1984 after Jamestown’s late president and founder William Geimer’s work with Arkady Shevchenko, the highest-ranking Soviet official ever to defect when he left his position as undersecretary general of the United Nations, the Jamestown Foundation rapidly became the leading source of information about the inner workings of closed totalitarian societies. -

Zois Report 6/2020

No. 6 / 2020 · November 2020 ZOiS REPORT BELARUS: FROM THE OLD SOCIAL CONTRACT TO A NEW SOCIAL IDENTITY Nadja Douglas ZOiS Report 6 / 2020 Belarus: From the old social contract to a new social identity Content 02 ___ Summary 03 ___ Introduction 05 ___ Social security vs. state security 05 ______ Long-term socio-economic developments 11 ______ Securitisation of state politics 15 ___ A protest-averse society begins to mobilise 16 ______ 2017 as a prelude to 2020 17 ______ From self-organisation to social reinvention 19 ______ Grassroots and individual (female) activists take over 20 ___ Interaction between citizens and the security forces 20 ______ Culture of impunity 22 ______ Countermeasures by the state 23 ___ Conclusion 24 ___ Interviews 24 ___ Imprint Summary State-society relations in Belarus have been tense for many years. The presi- dential elections in August 2020 and the mishandling of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic have proved to be the catalyst that brought these fragile relations to a complete breakdown. Over the years, the widening gap between a new generation of an emancipated citizenry and a regime stuck in predominantly paternalistic power structures and reluctant to engage in political and eco- nomic reforms has become increasingly evident. The deteriorating economy during the last decade and the perceived decline of the country’s social wel- fare system have been important factors in these developments. At the same time, the regime has continued to invest in its domestic security structures to a disproportionate extent compared with neighbouring states, allowing the so-called silovye struktury (“state power structures”) to gain influence at the highest level of state governance. -

Provisional Edition

European Parliament 2019-2024 TEXTS ADOPTED Provisional edition P9_TA-PROV(2020)0280 Recommendation to the Council, the Commission and the VPC/HR on relations with Belarus European Parliament recommendation of 21 October 2020 to the Council, the Commission and the Vice-President of the Commission / High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy on relations with Belarus (2020/2081(INI)) The European Parliament, – having regard to Articles 2, 3 and 8 and Title V, notably Articles 21, 22, 36 and 37, of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), and to Part Five of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), – having regard to the Council conclusions on Belarus of 15 February 2016, – having regard to the launch of the Eastern Partnership in Prague on 7 May 2009 as a common endeavour of the EU and its six Eastern European Partners, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, the Republic of Moldova and Ukraine, – having regard to the Joint Declarations of the Eastern Partnership Summits of 2009 in Prague, 2011 in Warsaw, 2013 in Vilnius, 2015 in Riga and 2017 in Brussels, and to the Eastern Partnership leaders' videoconference held in 2020, – having regard to the agreement between the European Union and the Republic of Belarus on the readmission of persons residing without authorisation, which entered into force on 1 July 20201, – having regard to the agreement between the European Union and the Republic of Belarus on the facilitation of the issuance of visas2 , which entered into force on 1 July 2020, – having regard to the 6th round of the bilateral Human Rights Dialogue between the EU and Belarus held on 18 June 2019 in Brussels, 1 OJ L 181, 9.6.2020, p. -

The Government of Belarus: Crushing Human Rights at Home?

THE GOVERNMENT OF BELARUS: CRUSHING HUMAN RIGHTS AT HOME? JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, AND HUMAN RIGHTS AND THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON EUROPE AND EURASIA OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 1, 2011 Serial No. 112–56 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 65–497PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:51 Oct 04, 2011 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\AGH\040111\65497 HFA PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey HOWARD L. BERMAN, California DAN BURTON, Indiana GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York ELTON GALLEGLY, California ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DANA ROHRABACHER, California Samoa DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey EDWARD R. ROYCE, California BRAD SHERMAN, California STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York RON PAUL, Texas GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York MIKE PENCE, Indiana RUSS CARNAHAN, Missouri JOE WILSON, South Carolina ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey CONNIE MACK, Florida GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia JEFF FORTENBERRY, Nebraska THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas DENNIS CARDOZA, California TED POE, Texas BEN CHANDLER, Kentucky GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida BRIAN HIGGINS, New York JEAN SCHMIDT, Ohio ALLYSON SCHWARTZ, Pennsylvania BILL JOHNSON, Ohio CHRISTOPHER S. -

Belarus by Alexei Pikulik, Dzianis Melyantsou Et Al

Belarus by Alexei Pikulik, Dzianis Melyantsou et al. Capital: Minsk Population: 9.5 million GNI/capita, PPP: US$14,460 Source: The data above are drawn from the World Bank’sWorld Development Indicators 2013. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Electoral Process 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 6.75 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 Civil Society 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.50 6.50 6.25 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.50 Independent Media 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 Governance* 6.50 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic Governance n/a 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Local Democratic Governance n/a 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Judicial Framework and Independence 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 7.00 7.00 Corruption 5.75 6.00 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.00 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.25 Democracy Score 6.54 6.64 6.71 6.68 6.71 6.57 6.50 6.57 6.68 6.71 * Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

(Pro)Testing Heritage, (Re)Searching Identity: Belarus Uprising – Studying National Perspectives

(Pro)testing heritage, (re)searching identity: Belarus uprising – studying national perspectives Retrieved from Office Life Media By: Dzmitry Sialitski [559242] Supervisor: Nicky van Es Tourism, Culture and Society Erasmus School of History, Culture & Communication Erasmus University Rotterdam Master Thesis June 14, 2021 ABSTRACT Protests in Belarus that started at the height of the presidential campaign in June 2020 and gained a massive scale in August have been going on for a year. Despite the suppression of large demonstrations, the conflict is actively unfolding in a symbolic 'world': conflicting sides – the pro-Soviet one backing by the government and the pro-democratic one represented by the protesters – try to undermine each other's cultural and ideological foundations, acting on the level of identity. Heritage – its mobilizing tool – is used both to attack and defend, given its political undertone. Young people as the future generation are an important target audience in this regard. Therefore, how and in what ways do both sides of the current protests in Belarus utilize heritage as a symbolic(-political) instrument, and how is this being negotiated by young Belarusians in constructing a sense of national identity? The interview method has been adopted to assess the multi-layered interplay between heritage and national identity in the context of Belarusian protests. Based on thorough communication with ten respondents, the research results show that through heritage, conflicting sides establish contact with politically 'beneficial' eras and adapt their principles to existing needs. The pro-Soviet side, accordingly, turns to heritage of the USSR, precisely one of the Great Patriotic War, to expose protesters as Nazis. -

Democratic Transition in Belarus: Cause(S) of Failure

STUDENT PAPER SERIES03 Democratic Transition in Belarus: Cause(s) of Failure Yauheniya Nechyparenka Master’s in International Relations Academic year 2010-2011 I hereby certify that this dissertation contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I hereby grant to IBEI the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this dissertation. Yauheniya Nechyparenka Word count: 9 995 Mount Kisco, NY 30/09/20 Table of Contents I. Introduction 1. Introduction 2 2. Methodology and structure 3 II. Literature review and theoretical framework 4 1 ‘Political’ hypothesis 7 2. ‘Social’ hypothesis 8 3. ‘External Forces’ hypotheses: 3.1. International democracy assistance 9 3.2. The relationship with autocratic hegemon 11 III. Case-study Analysis: Belarus 12 1. Unpopular incumbent leader - united opposition 14 2. Youth movement 16 3. Western-funded international organizations 19 4. Relationship with Russia 22 IV. Conclusion 27 V. References 28 i ABSTRACT The purpose of the research is to identify the causes of the constant fail of the ‘electoral’ democratic transition in the Republic of Belarus in the last decade. -

Belarus Page 1 of 28

Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Belarus Page 1 of 28 Belarus Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2007 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 11, 2008 Under its constitution, the Republic of Belarus, with a population of 9.7 million, has a directly elected president and a bicameral National Assembly. Since his election in 1994 as president, Alexander Lukashenko has systematically undermined the country's democratic institutions and concentrated power in the executive branch through authoritarian means, flawed referenda, manipulated elections, and arbitrary decrees that undermine the rule of law. Presidential elections in March 2006 that declared Lukashenko president for a third consecutive term again failed to meet international standards for democratic elections. The government continued to ignore recommendations by major international organizations to improve election processes and human rights. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces; however, members of the security forces committed numerous human rights abuses. The government's human rights record remained very poor and worsened in some areas as government authorities continued to commit frequent serious abuses. The government failed to account for past disappearances of opposition political figures and journalists. Prison conditions were extremely poor, and there were numerous reports of abuse of prisoners and detainees. Arbitrary arrests, detentions, and imprisonment of citizens for political reasons, criticizing officials, or for participating in demonstrations were common. Court trials occasionally were conducted behind closed doors without the benefit of independent observers. The judiciary branch lacked independence and trial outcomes were usually predetermined. The government further restricted civil liberties, including freedoms of press, speech, assembly, association, and religion.