Democratic Transition in Belarus: Cause(S) of Failure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ture in the Czech Republic

Brno 15 November 2020 Establishment of the Embassy of Independent Belarusian Cul- ture in the Czech Republic The Centre for Experimental Theatre in Brno (CED), which includes the Husa na Provazku Thea- tre, HaDivadlo and the Teren Platform, is setting up an Embassy of Independent Belarusian Culture in the Czech Republic in Brno. The opening of the embassy is symbolically directed to November 17, which is a national holiday in the Czech Republic and a Day of the Struggle for Freedom and Democracy. The Czechs have experience with both the totalitarian regime and civic protests against un- democratic behaviour and their subsequent repression. Therefore, in recent months, the Centre for Experimental Theatre has been closely following events in Belarus, where people have been fighting for fair elections, freedom and democracy for four months now, despite widespread ar- rests, imprisonment, harsh repression and intimidation. On Tuesday, November 17, 2020, we commemorate the anniversary of the Velvet Revolution and the victory of freedom and democracy in our country. The Centre for Experimental Theatre intends to follow the legacy of Vaclav Havel on this important day, and this time it is going to use the ethos of this day to commemorate what is happening in Belarus these days. „We contemplated what form would be the best to choose and agreed that it is not very useful to organize a one-day debate or similar event, but that most of all it is necessary to continu- ously and consistently inform the general public in the longer term about what is happening in Belarus these days. -

Dear Delegates, Congratulations on Being Selected to the Kremlin, One of VMUN's Most Advanced Committees. My Name Is Harrison

Dear Delegates, Congratulations on being selected to the Kremlin, one of VMUN’s most advanced committees. My name is Harrison Ritchie, and I will be your director for this year’s conference. I have been involved in MUN since Grade 10, and have thoroughly enjoyed every conference that I have attended. This year’s Kremlin will be a historical crisis committee. In February, you will all be transported to the October of 1988, where you will be taking on the roles of prominent members of either the Soviet Politburo or Cabinet of Ministers. As powerful Soviet officials, you will be debating the fall of the Soviet Union, or, rather, how to keep the Union together in such a tumultuous time. In the Soviet Union’s twilight years, a ideological divide began to emerge within the upper levels of government. Two distinct blocs formed out of this divide: the hardliners, who wished to see a return to totalitarian Stalinist rule, and the reformers, who wished to progress to a more democratic Union. At VMUN, delegates will hold the power to change the course of history. By exacting your influence upon your peers, you will gain valuable allies and make dangerous enemies. There is no doubt that keeping the Union together will be no easy task, and there are many issues to address over the coming three days, but I hope that you will be thoroughly engrossed in the twilight years of one of the world’s greatest superpower and find VMUN an overall fulfilling experience. Good luck in your research, and as always, if you have any questions, feel free to contact me before the conference. -

Belarus Country Report BTI 2014

BTI 2014 | Belarus Country Report Status Index 1-10 4.31 # 101 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 3.93 # 99 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 4.68 # 90 of 129 Management Index 1-10 2.80 # 119 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2014. It covers the period from 31 January 2011 to 31 January 2013. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2014 — Belarus Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2014 | Belarus 2 Key Indicators Population M 9.5 HDI 0.793 GDP p.c. $ 15592.3 Pop. growth1 % p.a. -0.1 HDI rank of 187 50 Gini Index 26.5 Life expectancy years 70.7 UN Education Index 0.866 Poverty3 % 0.1 Urban population % 75.4 Gender inequality2 - Aid per capita $ 8.8 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2013. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary Belarus faced one the greatest challenges of the Lukashenka presidency with the economic shocks that swept the country in 2011. The government’s own policies of politically motivated increases in state salaries and directed lending resulted in a balance of payments crisis, a massive decrease in central bank reserves, a currency crisis as queues formed at banks to change Belarusian rubles into dollars or euros, rampant hyperinflation, a devaluation of the national currency, and a significant drop in real incomes for Belarusian households. -

Protecting Democracy During COVID-19 in Europe and Eurasia and the Democratic Awakening in Belarus Testimony by Douglas Rutzen

Protecting Democracy During COVID-19 in Europe and Eurasia and the Democratic Awakening in Belarus Testimony by Douglas Rutzen President and CEO International Center for Not-for-Profit Law House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, Energy, and the Environment September 10, 2020 In April, Alexander Lukashenko declared that no one in Belarus would die of coronavirus.1 To allay concerns, he advised Belarussians to drink vodka, go to saunas, and drive tractors.2 In Hungary, Orban took a different approach. He admitted there was COVID-19, and he used this as an excuse to construct a legal framework allowing him to rule by decree.3 Meanwhile, China is using the pandemic to project its political influence. When a plane carrying medical aid landed in Belgrade, the Serbian President greeted the plane and kissed the Chinese flag. Billboards soon appeared in Belgrade, with Xi Jinping’s photo and the words “Thanks, Brother Xi” written in Serbian and Chinese.4 COVID-19 is not the root cause of Lukashenko’s deceit, Orban’s power grab, or China’s projection of political influence. But the pandemic exposed – and in some countries, exacerbated – underlying challenges to democracy. In my testimony, I will summarize pre-existing challenges to democracy. Second, I will examine how COVID-19 combined with pre-existing conditions to accelerate democratic decline in Europe and Eurasia. Third, I will share attributes of authoritarian and democratic responses to the pandemic. I will conclude with recommendations. Pre-Existing Challenges to Democracy According to Freedom House, 2019 marked the 14th year of decline in democracy around the world.5 The “democratic depression” is particularly acute in Eurasia, where the rule of law and freedom of expression declined more than in any other region.6 Indeed, Freedom House classifies zero countries in Eurasia as “free.” ICNL specializes in the legal framework for civil society, particularly the freedoms of association, peaceful assembly, and expression. -

BELARUS // Investing in Future Generations to Seize a ‘Demographic Dividend’

Realising Children’s Rights through Social Policy in Europe and Central Asia Action Area 2 A Compendium of UNICEF’s Contributions (2014-2020) 60 BELARUS // Investing in Future Generations to Seize a ‘Demographic Dividend’ © UNICEF/UN0218148/Noorani Realising Children’s Rights through Social Policy in Europe and Central Asia 61 A Compendium of UNICEF’s Contributions (2014-2020) Belarus Issue Belarus has made great progress in achieving its SDG aged 65 and older) per working-age adults aged 15-65 years indicators related to children and adolescents early. is 0.46.127 Thus, Belarus has a relatively low dependency ratio Nevertheless, one concern requiring rapid strategic and therefore wise investments in fewer dependents now attention is the exigency of seizing the country’s could effectively enable the next generation of workers to pay ‘demographic dividend’. After a two-year recession, pension contributions and to look after a larger dependent Belarus’ economic situation improved in 2017 and child population. Together, 19% or 138,000 adolescents experience poverty decreased to 10.4% in 2018. This represented an vulnerabilities128 (i.e. substance use, conflicts with the law, improvement on recent years, although the historical low violence, mental health challenges, disability, and living without remains the 9.2% achieved in 2014.125 However, in 2019 the family care or in poverty etc.).129 If not addressed promptly, country again faced an economic slowdown. In the midterm, those vulnerabilities, especially multidimensional ones, will the World Bank (WB) projects GDP growth of around 1%, have adverse impacts on their quality and longevity of life below what is needed to raise living standards. -

Prospects for Democracy in Belarus

An Eastern Slavic Brotherhood: The Determinative Factors Affecting Democratic Development in Ukraine and Belarus Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nicholas Hendon Starvaggi, B.A. Graduate Program in Slavic and East European Studies The Ohio State University 2009 Thesis Committee: Trevor Brown, Advisor Goldie Shabad Copyright by Nicholas Hendon Starvaggi 2009 Abstract Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, fifteen successor states emerged as independent nations that began transitions toward democratic governance and a market economy. These efforts have met with various levels of success. Three of these countries have since experienced “color revolutions,” which have been characterized by initial public demonstrations against the old order and a subsequent revision of the rules of the political game. In 2004-2005, these “color revolutions” were greeted by many international observers with optimism for these countries‟ progress toward democracy. In hindsight, however, the term itself needs to be assessed for its accuracy, as the political developments that followed seemed to regress away from democratic goals. In one of these countries, Ukraine, the Orange Revolution has brought about renewed hope in democracy, yet important obstacles remain. Belarus, Ukraine‟s northern neighbor, shares many structural similarities yet has not experienced a “color revolution.” Anti- governmental demonstrations in Minsk in 2006 were met with brutal force that spoiled the opposition‟s hopes of reenacting a similar political outcome to that which Ukraine‟s Orange Coalition was able to achieve in 2004. Through a comparative analysis of these two countries, it is found that the significant factors that prevented a “color revolution” in Belarus are a cohesive national identity that aligns with an authoritarian value system, a lack of engagement with U.S. -

Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past: a Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region

CBEES State of the Region Report 2020 Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region Published with support from the Foundation for Baltic and East European Studies (Östersjstiftelsen) Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region December 2020 Publisher Centre for Baltic and East European Studies, CBEES, Sdertrn University © CBEES, Sdertrn University and the authors Editor Ninna Mrner Editorial Board Joakim Ekman, Florence Frhlig, David Gaunt, Tora Lane, Per Anders Rudling, Irina Sandomirskaja Layout Lena Fredriksson, Serpentin Media Proofreading Bridget Schaefer, Semantix Print Elanders Sverige AB ISBN 978-91-85139-12-5 4 Contents 7 Preface. A New Annual CBEES Publication, Ulla Manns and Joakim Ekman 9 Introduction. Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past, David Gaunt and Tora Lane 15 Background. Eastern and Central Europe as a Region of Memory. Some Common Traits, Barbara Trnquist-Plewa ESSAYS 23 Victimhood and Building Identities on Past Suffering, Florence Frhlig 29 Image, Afterimage, Counter-Image: Communist Visuality without Communism, Irina Sandomirskaja 37 The Toxic Memory Politics in the Post-Soviet Caucasus, Thomas de Waal 45 The Flag Revolution. Understanding the Political Symbols of Belarus, Andrej Kotljarchuk 55 Institutes of Trauma Re-production in a Borderland: Poland, Ukraine, and Lithuania, Per Anders Rudling COUNTRY BY COUNTRY 69 Germany. The Multi-Level Governance of Memory as a Policy Field, Jenny Wstenberg 80 Lithuania. Fractured and Contested Memory Regimes, Violeta Davoliūtė 87 Belarus. The Politics of Memory in Belarus: Narratives and Institutions, Aliaksei Lastouski 94 Ukraine. Memory Nodes Loaded with Potential to Mobilize People, Yuliya Yurchuk 106 Czech Republic. -

The EU and Belarus – a Relationship with Reservations Dr

BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION EDITED BY DR. HANS-GEORG WIECK AND STEPHAN MALERIUS VILNIUS 2011 UDK 327(476+4) Be-131 BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION Authors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Dr. Vitali Silitski, Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann, Andrei Yahorau, Dr. Svetlana Matskevich, Valeri Fadeev, Dr. Andrei Kazakevich, Dr. Mikhail Pastukhou, Leonid Kalitenya, Alexander Chubrik Editors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Stephan Malerius This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies and the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication has received funding from the European Parliament. Sole responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication rests with the authors. The Centre for European Studies, the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility either for the information contained in the publication or its subsequent use. ISBN 978-609-95320-1-1 © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin / Berlin © Front cover photo: Jan Brykczynski CONTENTS 5 | Consultancy PROJECT: BELARUS AND THE EU Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck 13 | BELARUS IN AN INTERnational CONTEXT Dr. Vitali Silitski 22 | THE EU and BELARUS – A Relationship WITH RESERvations Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann 34 | CIVIL SOCIETY: AN analysis OF THE situation AND diRECTIONS FOR REFORM Andrei Yahorau 53 | Education IN BELARUS: REFORM AND COOPERation WITH THE EU Dr. Svetlana Matskevich 70 | State bodies, CONSTITUTIONAL REALITY AND FORMS OF RULE Valeri Fadeev 79 | JudiciaRY AND law -

Яюm I C R O S O F T W O R

Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) MASS MEDIA IN BELARUS 2004 ANNUAL REPORT Minsk 2005 C O N T E N T S INFRINGEMENTS OF FREEDOM OF MASS INFORMATION IN BELARUS IN 2004. REVIEW /2 STATISTICAL BACKGROUND /3 CHANGES IN THE LEGISLATION /5 INFRINGEMENTS OF RIGHTS OF MASS-MEDIA AND JOURNALISTS, CONFLICTS IN THE SPHERE OF MASS-MEDIA Criminal cases for publications in mass-media /13 Encroachments on journalists and media /16 Termination or suspension of mass-media by authorities /21 Detentions of journalists, summoning journalists to law enforcement bodies. Warnings of the Office of Public Prosecutor /29 Censorship. Interference in professional independence of editions /35 Infringements related to access to information (refusals in granting information, restrictive use of institute of accreditation) /40 The conflicts related to reception and dissemination of foreign information or activity of foreign mass-media /47 Economic policy in the sphere of mass-media /53 Restriction of the right on founding mass-media /57 Interference with production of mass-media /59 Hindrance to distribution of mass-media production /62 SENSATIONAL CASES The most significant litigations with participation of mass-media and journalists /70 Dmitry Zavadsky's case /79 Belarusian periodic printed editions mentioned in the monitoring /81 1 INFRINGEMENTS OF FREEDOM OF MASS INFORMATION IN BELARUS IN 2004. REVIEW The year 2004 for Belarus was the year of parliamentary elections and the referendum. As usual during significant political campaigns, the pressure on mass-media has increased in 2004. The deterioration of the media situation was not a temporary deviation after which everything usually comes back to normal, but represented strengthening of systematic and regular pressure upon mass- media, which continued after the election campaign. -

Belarus - a Unique Case in the European Context?

Belarus - A Unique Case in the European Context? By Peter Kim Laustsen* Introduction Remaking of World Order2 , where he ex- Federation, Ukraine, Romania, Bosnia and pressed a more pessimistic view. It was Herzegovina, Croatia, the Former Since the end of the Cold War and the claimed that the spreading of liberal de- Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and break-up of the Soviet Union, a guiding mocracy had reached its limits and that Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) did paradigm in the discussions concerning outside its present boundaries (primarily support Huntingtons theory. political changes in Central and Eastern Western Europe) this form of government The development in the latest years has Europe has been a positive and optimis- would not be able to take root. shown progress in all but a few of the tic believe in progress towards the vic- The political development that took above mentioned states. Reading Freedom tory of a liberal democracy. This view was place in the years after the fall of the Ber- Houses surveys on the level of political clearly expressed by Francis Fukuyama in lin Wall and the birth and rebirth of the rights and civil liberties gives hope. his widely discussed book The End of successor states of the Soviet Union, Widely across Europe these rights and lib- History and the Last Man1 . The optimistic Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia did not erties have been and are still expanding view of the political changes was however however support Fukuyamas claim. On and deepening. One state does clearly sepa- challenged by Samuel P. Huntington in the contrary, the political upheaval in, for rate itself from the trends in Eastern and his book The Clash of Civilizations and the instance, Slovakia, Belarus, the Russian Central Europe: Belarus. -

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

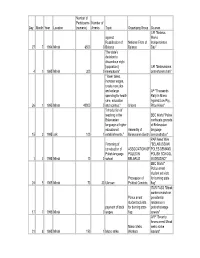

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Democratic Civil Society - an Alternative to the Autocratic Lukashenko Regime in Belarus

In: IFSH (ed.), OSCE Yearbook 2002, Baden-Baden 2003, pp. 219-235. Hans-Georg Wieck1 Democratic Civil Society - An Alternative to the Autocratic Lukashenko Regime in Belarus The Work of the OSCE Advisory and Monitoring Group in Belarus 1999-20012 In the past six years, the three major European institutions - the OSCE, the Council of Europe and the European Union - have promoted the development of democratic structures in Belarusian civil society as a political alternative to the autocratic Lukashenko system imposed on the country through a consti- tutional coup d’état in November 1996. Since then, the Lukashenko regime has been backed politically and economically by the Russian Federation. Testing the Ability of the Lukashenko Regime to Reform After the failure of the alternative presidential elections of May 19993 Alex- ander Lukashenko had nothing to fear immediately from the West’s reaction to the loss of his democratic legitimation. However, he suffered a painful de- feat in another field, which he hoped to compensate for by opening doors to the West: At literally the very last minute, Boris Yeltsin, due to the interven- tions of influential Russian political circles (among others, Anatoli Chubais), evaded Lukashenko’s plan in the summer of 1999 to conduct direct elections for the offices of President and Vice-President of the Union between the Rus- sian Federation and Belarus, in which Yeltsin was to run for President and Lukashenko for Vice-President. The elections were to take place simultane- ously in Russia and Belarus. In view of his popularity in Russia, which he had gained by systematically travelling there, Lukashenko could, also in Rus- sia, certainly have won the vote for the Vice-Presidency of the Union with a large majority.