Straddling Russia and Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Individual V. State: Practice on Complaints with the United Nations Treaty Bodies with Regards to the Republic of Belarus

Individual v. State: Practice on complaints with the United Nations treaty bodies with regards to the Republic of Belarus Volume I Collection of articles and documents The present collection of articles and documents is published within the framework of “International Law in Advocacy” program by Human Rights House Network with support from the Human Rights House in Vilnius and Civil Rights Defenders (Sweden) 2012 UDC 341.231.14 +342.7 (476) BBK 67.412.1 +67.400.7 (4Bel) I60 Edited by Sergei Golubok Candidate of Law, Attorney of the St. Petersburg Bar Association, member of the editorial board of the scientific journal “International justice” I60 “Individual v. State: Practice on complaints with the United Nations treaty bodies with regards to the Republic of Belarus”. – Vilnius, 2012. – 206 pages. ISBN 978-609-95300-1-7. The present collection of articles “Individual v. State: Practice on complaints with the United Nations treaty bodies with regards to the Republic of Belarus” is the first part of the two-volume book, that is the fourth publication in the series about international law and national legal system of the republic of Belarus, implemented by experts and alumni of the Human Rights Houses Network‘s program “International Law in Advocacy” since 2007. The first volume of this publication contains original writings about the contents and practical aspects of international human rights law concepts directly related to the Institute of individual communications, and about the role of an individual in the imple- mentation of international legal obligations of the state. The second volume, expected to be published in 2013, will include original analyti- cal works on the admissibility of individual considerations and the Republic of Belarus’ compliance with the decisions (views) by treaty bodies. -

Heads of State Heads of Government Ministers For

UNITED NATIONS HEADS OF STATE Protocol and Liaison Service HEADS OF GOVERNMENT PUBLIC LIST MINISTERS FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS COUNTRY HEAD OF STATE HEAD OF GOVERNMENT MINISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS AFGHANISTAN His Excellency Same as Head of State His Excellency Mr. Mohammad Ashraf Ghani Mr. Mohammad Haneef Atmar Full Title President of the Islamic Republic of Acting Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Afghanistan Republic of Afghanistan Date of Appointment 29-Sep-14 04-Apr-20 ALBANIA His Excellency His Excellency same as Prime Minister Mr. Ilir Meta Mr. Edi Rama Full Title President of the Republic of Albania Prime Minister and Minister for Europe and Foreign Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs of the Affairs of the Republic of Albania Republic of Albania Date of Appointment 24-Jul-17 15-Sep-13 21-Jan-19 ALGERIA Son Excellence Son Excellence Son Excellence Monsieur Abdelmadjid Tebboune Monsieur Abdelaziz Djerad Monsieur Sabri Boukadoum Full Title Président de la République algérienne Premier Ministre de la République algérienne Ministre des Affaires étrangères de la République démocratique et populaire démocratique et populaire algérienne démocratique et populaire Date of Appointment 19-Dec-19 05-Jan-20 31-Mar-19 21/08/2020 Page 1 of 66 COUNTRY HEAD OF STATE HEAD OF GOVERNMENT MINISTER FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS ANDORRA Son Excellence Son Excellence Son Excellence Monseigneur Joan Enric Vives Sicília Monsieur Xavier Espot Zamora Madame Maria Ubach Font et Son Excellence Monsieur Emmanuel Macron Full Title Co-Princes de la Principauté d’Andorre Chef du Gouvernement de la Principauté d’Andorre Ministre des Affaires étrangères de la Principauté d’Andorre Date of Appointment 16-May-12 21-May-19 17-Jul-17 ANGOLA His Excellency His Excellency Mr. -

Information Translation JSC Inter RAO 2014 Annual Report

1 Information translation JSC Inter RAO 2014 Annual Report Preliminarily approved by the Board of Directors of JSC Inter RAO on April 07, 2015 (Minutes No. 138 of the meeting of the Board of Directors dated April 09, 2015). Management Board Boris Kovalchuk Chairman Chief Accountant Alla Vaynilavichute 2 Table of content 1 Report overview ........................................................................................................................ 4 2 General information on Inter RAO Group .................................................................................. 8 2.1 About Inter RAO Group ..................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Group's key performance indicators ................................................................................. 14 2.3 Inter RAO Group on the energy market ........................................................................... 15 2.4 Associations and partnerships ......................................................................................... 15 3 Statement for JSC Inter RAO shareholders and other stakeholders ........................................ 18 4 Development strategy of Inter RAO Group and its implementation ......................................... 21 4.1 Strategy of the Company ................................................................................................. 21 4.2 Business model .............................................................................................................. -

Belarus Country Report BTI 2014

BTI 2014 | Belarus Country Report Status Index 1-10 4.31 # 101 of 129 Political Transformation 1-10 3.93 # 99 of 129 Economic Transformation 1-10 4.68 # 90 of 129 Management Index 1-10 2.80 # 119 of 129 scale score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2014. It covers the period from 31 January 2011 to 31 January 2013. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2014 — Belarus Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. BTI 2014 | Belarus 2 Key Indicators Population M 9.5 HDI 0.793 GDP p.c. $ 15592.3 Pop. growth1 % p.a. -0.1 HDI rank of 187 50 Gini Index 26.5 Life expectancy years 70.7 UN Education Index 0.866 Poverty3 % 0.1 Urban population % 75.4 Gender inequality2 - Aid per capita $ 8.8 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2013. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary Belarus faced one the greatest challenges of the Lukashenka presidency with the economic shocks that swept the country in 2011. The government’s own policies of politically motivated increases in state salaries and directed lending resulted in a balance of payments crisis, a massive decrease in central bank reserves, a currency crisis as queues formed at banks to change Belarusian rubles into dollars or euros, rampant hyperinflation, a devaluation of the national currency, and a significant drop in real incomes for Belarusian households. -

Evolution of Belarusian-Polish Relations at the Present Stage: Balance of Interests

Журнал Белорусского государственного университета. Международные отношения Journal of the Belarusian State University. International Relations UDC 327(476:438) EVOLUTION OF BELARUSIAN-POLISH RELATIONS AT THE PRESENT STAGE: BALANCE OF INTERESTS V. G. SHADURSKI а aBelarusian State University, Nezavisimosti avenue, 4, Minsk, 220030, Republic of Belarus The present article is dedicated to the analysis of the Belarusian-Polish relations’ development during the post-USSR period. The conclusion is made that despite the geographical neighborhood of both countries, their cultural and historical proximity, cooperation between Minsk and Warsaw didn’t comply with the existing capacity. Political contradictions became the reason for that, which resulted in fluctuations in bilateral cooperation, local conflicts on the inter-state level. The author makes an attempt to identify the main reasons for a low level of efficiency in bilateral relations and to give an assessment of foreign factors impact on Minsk and Warsaw policies. Key words: Belarusian-Polish relations; Belarusian foreign policy; Belarusian and Polish diplomacy; historical policy. ЭВОЛЮЦИЯ БЕЛОРУССКО-ПОЛЬСКИХ ОТНОШЕНИЙ НА СОВРЕМЕННОМ ЭТАПЕ: ПОИСК БАЛАНСА ИНТЕРЕСОВ В. Г. ШАДУРСКИЙ 1) 1)Белорусский государственный университет, пр. Независимости, 4, 220030, г. Минск, Республика Беларусь В представленной публикации анализируется развитие белорусско-польских отношений на протяжении периода после распада СССР. Делается вывод о том, что, несмотря на географическое соседство двух стран, их культурную и историческую близость, сотрудничество Минска и Варшавы не соответствовало имеющемуся потенциалу. При- чиной тому являлись политические разногласия, следствием которых стали перепады в двухстороннем взаимодей- ствии, частые конфликты на межгосударственном уровне. Автор пытается выяснить основные причины невысокой эффективности двусторонних связей, дать оценку влияния внешних факторов на политику Минска и Варшавы. -

No. 21 TRONDHEIM STUDIES on EAST EUROPEAN CULTURES

No. 21 TRONDHEIM STUDIES ON EAST EUROPEAN CULTURES & SOCIETIES David R. Marples THE LUKASHENKA PHENOMENON Elections, Propaganda, and the Foundations of Political Authority in Belarus August 2007 David R. Marples is University Professor at the Department of History & Classics, and Director of the Stasiuk Program for the Study of Contemporary Ukraine of the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. His recent books include Heroes and Villains. Constructing National History in Contemporary Ukraine (2007), Prospects for Democracy in Belarus, co-edited with Joerg Forbrig and Pavol Demes (2006), The Collapse of the Soviet Union, 1985-1991(2004), and Motherland: Russia in the 20th Century (2002). © 2007 David R Marples and the Program on East European Cultures and Societies, a program of the Faculties of Arts and Social Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology. ISSN 1501-6684 ISBN 978-82-995792-1-6 Trondheim Studies on East European Cultures and Societies Editors: György Péteri and Sabrina P. Ramet Editorial Board: Trond Berge, Tanja Ellingsen, Knut Andreas Grimstad, Arne Halvorsen We encourage submissions to the Trondheim Studies on East European Cultures and Societies. Inclusion in the series will be based on anonymous review. Manuscripts are expected to be in English (exception is made for Norwegian Master’s and PhD theses) and not to exceed 150 double spaced pages in length. Postal address for submissions: Editor, Trondheim Studies on East European Cultures and Societies, Department of History, NTNU, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway. For more information on PEECS and TSEECS, visit our web-site at http://www.hf.ntnu.no/peecs/home/ The photo on the cover is a copy of an item included in the photo chronicle of the demonstration of 21 July 2004 and made accessible by the Charter ’97 at http://www.charter97.org/index.phtml?sid=4&did=july21&lang=3 TRONDHEIM STUDIES ON EAST EUROPEAN CULTURES & SOCIETIES No. -

European Parliament

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2004 2009 Session document 13.9.2004 B6-0053/2004 MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION further to the Commission statement pursuant to Rule 103(2) of the Rules of Procedure by Konrad Krzysztof Szymański, Rolandas Pavilionis and Anna Elzbieta Fotyga on behalf of the Union for Europe of the Nations Group on Belarus RE\541355EN.doc PE 347.467 EN EN B6-0053/2004 European Parliament resolution on Belarus The European Parliament, – having regard to the forthcoming elections and referendum on further extending the Presidential term of office in Belarus, – having regard to the resolutions adopted by the UN Commission on Human Rights on Belarus in April 2003 and 2004 and the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly's Resolution No 1371/2004 on disappeared persons, – having regard to the decision of the UN Commission on Human Rights to appoint a special rapporteur on the situation in Belarus, – having regard to Rule 103(2) of the Rules of Procedure, A. whereas the situation as regards human rights, citizens’ rights and fundamental freedoms has reached a critical stage in Belarus, B. whereas the Belarusian authorities continue to demonstrate their unwillingness to tolerate any form of political opposition, C. alarmed at the numerous cases of opposition activists and independent journalists being detained, imprisoned, fined and expelled from universities, D. concerned at the continuing repression of the independent media and NGOs, E. deeply concerned at the reports of 'disappeared' persons in Belarus, 1. Calls on the Belarusian authorities to immediately guarantee the holding of free and fair elections by inviting the representatives of the opposition parties to play a full role as members and observers at every level of the work of electoral commissions; 2. -

State Composers and the Red Courtiers: Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930S

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Blomstedtin salissa marraskuun 24. päivänä 2007 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in the Building Villa Rana, Blomstedt Hall, on November 24, 2007 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Seppo Zetterberg Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Irene Ylönen, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä URN:ISBN:9789513930158 ISBN 978-951-39-3015-8 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-2990-9 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2007 ABSTRACT Mikkonen, Simo State composers and the red courtiers. -

Яюm I C R O S O F T W O R

Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) MASS MEDIA IN BELARUS 2004 ANNUAL REPORT Minsk 2005 C O N T E N T S INFRINGEMENTS OF FREEDOM OF MASS INFORMATION IN BELARUS IN 2004. REVIEW /2 STATISTICAL BACKGROUND /3 CHANGES IN THE LEGISLATION /5 INFRINGEMENTS OF RIGHTS OF MASS-MEDIA AND JOURNALISTS, CONFLICTS IN THE SPHERE OF MASS-MEDIA Criminal cases for publications in mass-media /13 Encroachments on journalists and media /16 Termination or suspension of mass-media by authorities /21 Detentions of journalists, summoning journalists to law enforcement bodies. Warnings of the Office of Public Prosecutor /29 Censorship. Interference in professional independence of editions /35 Infringements related to access to information (refusals in granting information, restrictive use of institute of accreditation) /40 The conflicts related to reception and dissemination of foreign information or activity of foreign mass-media /47 Economic policy in the sphere of mass-media /53 Restriction of the right on founding mass-media /57 Interference with production of mass-media /59 Hindrance to distribution of mass-media production /62 SENSATIONAL CASES The most significant litigations with participation of mass-media and journalists /70 Dmitry Zavadsky's case /79 Belarusian periodic printed editions mentioned in the monitoring /81 1 INFRINGEMENTS OF FREEDOM OF MASS INFORMATION IN BELARUS IN 2004. REVIEW The year 2004 for Belarus was the year of parliamentary elections and the referendum. As usual during significant political campaigns, the pressure on mass-media has increased in 2004. The deterioration of the media situation was not a temporary deviation after which everything usually comes back to normal, but represented strengthening of systematic and regular pressure upon mass- media, which continued after the election campaign. -

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

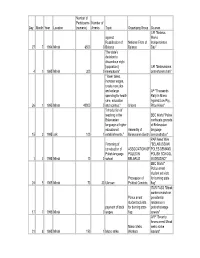

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Inter RAO Annual Report 201

JSC Inter RAO 2013 Annual Report Chairman of the Management Board Boris Yu. Kovalchuk Approved by The Annual General Meeting of Shareholders on May 25, 2014 (Minutes dated May 25, 2014 No. 14) Chief Accountant Alexandra O. Chesnokova TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. ABOUT THE REPORT _________________________________________________________________________________________________________3 7. THE COMPANY IN THE CAPITAL MARKETS _____________________________________________________________________131 2. GENERAL INFORMATION ON INTER RAO GROUP _______________________________________________________________5 8. CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY __________________________________________________________________________ 137 2.1. About Inter RAO Group _______________________________________________________________________________________________5 8.1. Approach to Sustainability _______________________________________________________________________________________ 137 2.2. The Group’s key indicators ___________________________________________________________________________________________9 8.2. Human Resources Management _______________________________________________________________________________ 138 2.3. Key events_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 10 8.3. Occupational Health and Safety _______________________________________________________________________________ 149 8.4. Contribution to the development of the regions of the Group’s operation _______________________ 154 3. STATEMENT -

Trydiy FMO 2016.Indd

ISSN 2219-2085 БЕЛОРУССКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ ТРУДЫ ФАКУЛЬТЕТА МЕЖДУНАРОДНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЙ Научный сборник Основан в 2010 году Выпуск VII МИНСК БГУ 2016 УДК 3(062.522)(082) Представлены научные статьи ведущих ученых факультета международных отношений Бело- русского государственного университета, в которых рассматриваются международные отношения и внешняя политика, международное право, мировые экономические процессы, межкультурная ком- муникация. Редакционная коллегия : доктор исторических наук, профессор В. Г. Шадурский (главный редактор); доктор исторических наук, доцент Л. М. Гайдукевич; доктор исторических наук, профессор А. А. Розанов; доктор исторических наук, профессор В. Е. Снапковский; доктор исторических наук, профессор А. А. Челядинский; доктор исторических наук, профессор А. В. Шарапо; кандидат исторических наук, доцент В. А. Острога; кандидат исторических наук, доцент А. В. Русакович; кандидат исторических наук А. В. Селиванов; доктор юридических наук, профессор С. А. Балашенко; доктор юридических наук, профессор Ю. П. Бровка; доктор юридических наук, профессор М. Ф. Чудаков; кандидат юридических наук, доцент Е. В. Бабкина; кандидат юридических наук, доцент А. Е. Вашкевич; кандидат юридических наук, доцент Е. Б. Леанович; кандидат юридических наук, доцент Ю. А. Лепешков; доктор экономических наук, доцент Е. Л. Давыденко; доктор экономических наук, профессор А. В. Данильченко; доктор экономических наук, профессор С. Ю. Солодовников; доктор экономических наук, профессор А. Е. Дайнеко; кандидат экономических наук, доцент